Shildon—Cradle of the Railways

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Historic Environment Audit Appendix 2. West Auckland to Shildon

The 1825 Stockton & Darlington Railway: Historic Environment Audit Appendix 2. West Auckland to Shildon. October 2016 Archaeo-Environment for Durham County Council, Darlington Borough Council and Stockton Council. The 1825 Stockton & Darlington Railway: Historic Environment Audit: West Auckland to Shildon. Introduction This report is one of a series covering the length of the 1825 Stockton & Darlington Railway. It results from a programme of fieldwork and desk based research carried out between October 2015 and March 2016 by Archaeo-Environment and local community groups, in particular the Friends of the 1825 S&DR. This appendix covers the second 5.1km (3.17 miles) stretch between the Gaunless Accommodation Bridge at West Auckland and Shildon (figure 1). It outlines what survives and what has been lost starting at the north and heading south east to Shildon. It outlines the gaps in our knowledge requiring further research and the major management issues needing action. It highlights opportunities for improved access to the line and for improved conservation, management and interpretation so that the S&DR is a visitor destination of national and international importance. © Crown copyright 2016. All rights reserved. Licence number 100042279. Figure 1. Area discussed in this document (inset S&DR Line against regional background). Archaeo-Environment Ltd for Durham County Council, Darlington Borough Council and Stockton Borough Council 1 S&DR 1825: Opportunities for Heritage – Led Regeneration: West Auckland to Shildon. Historic Background At 7am, on the 27th September 1825, 12 waggons of coal were hauled from the Phoenix Pit at Witton Park to the foot of Etherley Ridge, and pulled up the North Bank 1,100 yards by a stationary engine. -

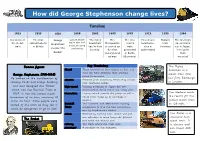

How Did George Stephenson Change Lives?

How did George Stephenson change lives? Timeline 1812 1825 1829 1850 1863 1863 1879 1912 1938 1964 Invention of The first George Luxury steam ‘The flying The The first First diesel Mallard The first high trains with soft the steam railroad opens Stephenson Scotsman’ Metropolitan electric locomotive train speed trains train in Britain seats, sleeping had its first is opened as train runs in invented run in Japan. invents ‘The and dining journey. the first presented Switzerland ‘The bullet Rocket’ underground in Berlin train railway (Germany) invented’ Key Vocabulary Famous figures The Flying diesel These locomotives burn diesel as fuel and Scotsman is a were far more powerful than previous George Stephenson (1781-1848) steam train that steam locomotives. He worked on the development of ran from Edinburgh electric Powered from electricity which they collect to London. railway tracks and bridge building from overhead cables. and also designed the ‘Rocket’ high-speed Initially produced in Japan but now which won the Rainhill Trials in international, these trains are really fast. The Mallard holds 1829. It was the fastest steam locomotive Engines which provide the power to pull a the record for the locomotive of its time, reaching 30 whole train made up of carriages or fastest steam train miles an hour. Some people were wagons. Rainhill The Liverpool and Manchester railway at 126 mph. scared of the train as they felt it Trials competition to find the best locomotive, could be dangerous to go so fast! won by Stephenson’s Rocket. steam Powered by burning coal. Steam was fed The Bullet is a into cylinders to move long rods (pistons) Japanese high The Rocket and make the wheels turn. -

Properties and Land Owned Or Occupied for the Purposes of Work of the PCC 2020

Properties and Land Owned or Occupied for the Purposes of Work of the PCC 2020 Asset Name AYKLEY HEADS FIELDS BARNARD CASTLE EMERGENCY SERVICES STATION BISHOP AUCKLAND POLICE STATION BLACKHALL BOWBURN CATCHGATE POLICE OFFICE CHESTER LE STREET POLICE STATION CONSETT POLICE STATION CROOK CIVIC CENTER CROOK POLICE STATION DARLINGTON COCKERTON POLICE OFFICE DARLINGTON POLICE STATION DURHAM POLICE STATION DURHAM SHERBURN ROAD POLICE OFFICE EASINGTON COLLIERY POLICE OFFICE FERRYHILL POLICE OFFICE FIRTHMOOR FRAMWELLGATE MOOR POLICE OFFICE GLADSTONE STREET HAWTHORNE QUARRY MEADOWFIELD MEADOWFIELD IND EST PUBLIC ORDER & RIOT UNIT MIDDRIDGE QUARRY NEWTON AYCLIFFE NEWTON AYCLIFFE (Fire Station) PELTON POLICE OFFICE PETERLEE POLICE STATION PETERLEE WAREHOUSE POLICE HEADQUARTERS RICKNALL LANE SEAHAM POLICE STATION SEDGEFIELD POLICE OFFICE SHILDON POLICE OFFICE SOUTH MOOR POLICE OFFICE SPENNYMOOR POLICE STATION STAINDROP POLICE OFFICE STANHOPE STANLEY POLICE STATION TEESSIDE AIRPORT THE BARNS Address Durham HQ, Aykley Heads, Durham DH1 5TT Wilson Street, Barnard Castle, County Durham DL12 8JU Woodhouse Lane, Bishop Auckland, County Durham DL14 6DL Middle Street, Blackhall Colliery, Peterlee, TS27 4ED Fire Training centre, BoWburn Industrial Estate North Road, Catchgate, County Durham DH9 8ED NeWcastle Road, Chester-le-Street, County Durham DH3 3TY Parliament Street, Consett, County Durham DH8 5DL 4th Floor, Crook Civic Centre, North Terrace, Crook, Co.Durham, DH15 9ES South Street, Crook, County Durham DL15 8NE 141 WilloW Road, Cockerton, Darlington -

The Evolution of the Steam Locomotive, 1803 to 1898 (1899)

> g s J> ° "^ Q as : F7 lA-dh-**^) THE EVOLUTION OF THE STEAM LOCOMOTIVE (1803 to 1898.) BY Q. A. SEKON, Editor of the "Railway Magazine" and "Hallway Year Book, Author of "A History of the Great Western Railway," *•., 4*. SECOND EDITION (Enlarged). £on&on THE RAILWAY PUBLISHING CO., Ltd., 79 and 80, Temple Chambers, Temple Avenue, E.C. 1899. T3 in PKEFACE TO SECOND EDITION. When, ten days ago, the first copy of the " Evolution of the Steam Locomotive" was ready for sale, I did not expect to be called upon to write a preface for a new edition before 240 hours had expired. The author cannot but be gratified to know that the whole of the extremely large first edition was exhausted practically upon publication, and since many would-be readers are still unsupplied, the demand for another edition is pressing. Under these circumstances but slight modifications have been made in the original text, although additional particulars and illustrations have been inserted in the new edition. The new matter relates to the locomotives of the North Staffordshire, London., Tilbury, and Southend, Great Western, and London and North Western Railways. I sincerely thank the many correspondents who, in the few days that have elapsed since the publication: of the "Evolution of the , Steam Locomotive," have so readily assured me of - their hearty appreciation of the book. rj .;! G. A. SEKON. -! January, 1899. PREFACE TO FIRST EDITION. In connection with the marvellous growth of our railway system there is nothing of so paramount importance and interest as the evolution of the locomotive steam engine. -

3 Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

3 bus time schedule & line map 3 Darlington View In Website Mode The 3 bus line (Darlington) has 3 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Darlington: 6:42 AM - 10:50 PM (2) Hummersknott: 7:42 AM - 5:52 PM (3) Skerne Park: 6:35 AM - 10:40 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 3 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 3 bus arriving. Direction: Darlington 3 bus Time Schedule 14 stops Darlington Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday 9:20 AM - 10:50 PM Monday 9:20 AM - 10:50 PM Coleridge Gardens, Skerne Park Swale Grove, Darlington Tuesday 6:42 AM - 10:50 PM Eden Crescent, Skerne Park Wednesday 6:42 AM - 10:50 PM Eden Crescent, Darlington Thursday 6:42 AM - 10:50 PM Lakeside, Skerne Park Friday 6:42 AM - 10:50 PM Arkle Crescent, Skerne Park Saturday 7:27 AM - 10:50 PM Esk Road, Skerne Park Tweed Place, Skerne Park Tweed Place, Darlington 3 bus Info Direction: Darlington Skerne Park Post O∆ce, Skerne Park Stops: 14 Trip Duration: 14 min Coleridge Centre, Skerne Park Line Summary: Coleridge Gardens, Skerne Park, Eden Crescent, Skerne Park, Lakeside, Skerne Park, Clifton Avenue, Darlington Arkle Crescent, Skerne Park, Esk Road, Skerne Park, Tweed Place, Skerne Park, Skerne Park Post O∆ce, Henderson Street, Darlington Skerne Park, Coleridge Centre, Skerne Park, Clifton Avenue, Darlington, Henderson Street, Darlington, Geneva Terrace, Darlington Waverley Terrace, Darlington, Victoria Road, Bank Waverley Terrace, Darlington Top, Northgate, Darlington, Tubwell Row, Darlington Victoria Road, Bank Top Northgate, -

Alma House, 49 West Auckland Road Cockerton, Darlington, DL3 9EL

FOR SALE – Price £195,000 Alma House, 49 West Auckland Road Cockerton, Darlington, DL3 9EL Investment Opportunity www.carvercommercial.com SITUATION/LOCATION TENANCY INFORMATION VAT The property is situated within the popular Unit A VAT is payable on the purchase price. The residential/shopping district of Cockerton Village Tenant - Michael Peart and Steven Peart (Village transaction will be treated as a transfer of going which lies approximately 1.5 miles north west of Optician) concern. Darlington town centre. The Cockerton area has 10 year efri lease, WEF October 2012, no breaks, rent th expanded considerably within the last 15 years review after 5 year (no increase). VIEWING with the development of West Park Village Rent passing £8,750 per annum plus service charge Strictly by appointment only through agents. incorporating circa 700 residential properties, Unit B ENERGY PERFORMANCE ASSET RATING hospital and school and more recently Marks and Spencer Simply Food and Aldi Supermarket. Tenant – First Flowers Ltd, guarantor Mark Fox Unit A - E-123 West Auckland Road is a main arterial road to 7 year efri lease WEF November 2015, break option Unit B - E-107 the A1M at Junction 58 approximately 1.9 miles May 2019 (subject to 6 months prior written notice). distant. Cockerton is well served by a variety of Rent review November 2017 (no increase) shops and amenities within convenient walking Rent Passing £7,000 per annum plus service charge distance. Total Rental Income £16,150 per annum (exclusive) PREMISES Alma House was originally a local public house The four apartments are each on 125 year leases and converted by our client approximately 7 paying annual ground rent in advance of £100 per years ago providing 2 self contained ground floor annum. -

The 1825 Stockton & Darlington Railway

The 1825 S&DR: Preparing for 2025; Significance & Management. The 1825 Stockton & Darlington Railway: Historic Environment Audit Volume 1: Significance & Management October 2016 Archaeo-Environment for Durham County Council, Darlington Borough Council and Stockton on Tees Borough Council. Archaeo-Environment Ltd for Durham County Council, Darlington Borough Council and Stockton Borough Council 1 The 1825 S&DR: Preparing for 2025; Significance & Management. Executive Summary The ‘greatest idea of modern times’ (Jeans 1974, 74). This report arises from a project jointly commissioned by the three local authorities of Darlington Borough Council, Durham County Council and Stockton-on-Tees Borough Council which have within their boundaries the remains of the Stockton & Darlington Railway (S&DR) which was formally opened on the 27th September 1825. The report identifies why the S&DR was important in the history of railways and sets out its significance and unique selling point. This builds upon the work already undertaken as part of the Friends of Stockton and Darlington Railway Conference in June 2015 and in particular the paper given by Andy Guy on the significance of the 1825 S&DR line (Guy 2015). This report provides an action plan and makes recommendations for the conservation, interpretation and management of this world class heritage so that it can take centre stage in a programme of heritage led economic and social regeneration by 2025 and the bicentenary of the opening of the line. More specifically, the brief for this Heritage Trackbed Audit comprised a number of distinct outputs and the results are summarised as follows: A. Identify why the S&DR was important in the history of railways and clearly articulate its significance and unique selling point. -

George Stephenson Fact File

George Stephenson Fact File • George Stephenson was born in 1781 near Newcastle-upon-Tyne. • His dad worked at a coal mine and looked after the steam engines that were used to pump water out of the mine. He taught George about these machines and when George was 14 he went to work down the mines himself. He would play about with the machines to learn more about how they worked. • In 1814, George designed his first steam locomotive for the railways for Killingworth Colliery near Newcastle. The loco was a success and George was asked to work on other railways being built. • In 1825 a new railway was opened between Stockton and Darlington. George and his men built the track and the locomotive for this railway. It later became the first steam loco to carry passengers in the world! • But the steam loco George is probably most famous for is the Rocket... - In 1829 a new railway was planned to run between Liverpool and Manchester. - George competed against two other engineers to find the best locomotive to run on the railway and pull heavy loads of materials over long distances. With his son, Robert, he built the ‘Rocket’. This travelled faster than all the other trains at 36mph. - The opening of this railway line and the success of the rocket led to many more railway lines and steam locomotives being built across the country. Richard Trevithick Fact File • In 1803 Trevithick began to build the first steam locomotive in Britain to run on rails. • He had been asked by the boss of an ironworks company in South Wales to build a steam loco to run on rails from the ironworks (a place where iron a strong metal is used to make things) to the local canal. -

Our Heritage Festival 2021 - Bishop Auckland and Stockton & Darlington Railway

Our Heritage Festival 2021 - Bishop Auckland and Stockton & Darlington Railway 10 - 27 September 2021 Bishop Auckland Heritage Action Zone and the Stockton & Darlington Railway Heritage Action Zone - working together to bring heritage to life Bookings: text or phone 07825 856451 Email: [email protected] Facebook: @bishopaucklandhaz . t e e r t S y a w l i a R Who do we think we are and what exactly is heritage? n o m u e Join in this journey of discovery and share your stories s u M s ’ and memories of the town and its people. Research e l p o e your family and local history, learn about the latest P e h t discoveries, enjoy free exhibitions and events – and w o n , enter our competition to win two free tickets to the e m o r last showing of Kynren on Saturday 11 September. d o p ip H ld The festival runs online, in person and on the radio. O e th r We’re delighted to be partnering with 105.9 Bishop FM. a ne d te Do join in and spread the word, wherever you are. ain l p ura A l m We look forward to seeing you. n aure n Stan L e A l l e n w i t h L o c a Anne Allen l l i s t i n Heritage Action Zone Project Manager g s o f ic e r s Eh . Bookings: text or phone 07825 856451 r k. s e c e n i Sm nd h ith Cu c and Georgia r A Email: [email protected] n e v le E t, Links to online activities will be posted on the Bishop Auckland Heritage uc ad vi The ay Action Zone website from 10 September www.durham.gov.uk/haz Victorian railw www.bishopfm.com Facebook: @bishopaucklandhaz Free tickets to Kynren competition Saturday 11 September is the last show this year of Kynren 11arches.com/kynren a sound and light show telling the story of England. -

Heritage Statement

HERITAGE STATEMENT Project: 14 Rose Lane Haughton le Skerne Client: Mr and Mrs Horton Our Ref: AH/123 Date: April 2021 1. Introduction This Heritage Statement has been produced on behalf of Mr and Mrs Horton in relation to an application for full Planning Permission for a erection of a an extension to existing rear ground floor extension with first floor extension above. The purpose of this statement is to demonstrate that consideration has been given to the impact of the proposed changes to the nearby heritage assets and the impact of the proposed development on the overall character and appearance of the surrounding area. 2. Site Location The property is situated in the village of Haughton Le Skerne on a road named Rose Lane.Haughton is a settlement less than one and half miles north east of Darlington town centre. As its name suggests it is located on the River Skerne, lying just north of it with the low-lying and flood-prone meadows still forming a divide between Darlington and Haughton-le-Skerne. The B6279 (Haughton Road, then Stockton Road) runs through the village, named Haughton Green in the centre of the village as it passes the Village Green. This road joins the A1150 and ultimately the A66 east towards Teesside. To the west Haughton Green becomes Salters Lane South past St Andrew’s Church. Both Haughton Green and the surrounding undeveloped greenspace to the south and east play a key part in characterising the area’s setting 3. History and Context The property comprises the main semi detached dwelling house with a single storey rear extension which forms the bathroom. -

Hackworth Family Archive

Hackworth Family Archive A cataloguing project made possible by the National Cataloguing Grants Programme for Archives Science Museum Group 1 Description of Entire Archive: HACK (fonds level description) Title Hackworth Family Archive Fonds reference code GB 0756 HACK Dates 1810’s-1980’s Extent & Medium of the unit of the 1036 letters with accompanying letters and associated documents, 151 pieces of printed material and printed images, unit of description 13 volumes, 6 drawings, 4 large items Name of creator s Hackworth Family Administrative/Biographical Hackworth, Timothy (b 1786 – d 1850), Railway Engineer was an early railway pioneer who worked for the Stockton History and Darlington Railway Company and had his own engineering works Soho Works, in Shildon, County Durham. He married and had eight children and was a converted Wesleyan Methodist. He manufactured and designed locomotives and other engines and worked with other significant railway individuals of the time, for example George and Robert Stephenson. He was responsible for manufacturing the first locomotive for Russia and British North America. It has been debated historically up to the present day whether Hackworth gained enough recognition for his work. Proponents of Hackworth have suggested that he invented of the ‘blast pipe’ which led to the success of locomotives over other forms of rail transport. His sons other relatives went on to be engineers. His eldest son, John Wesley Hackworth did a lot of work to promote his fathers memory after he died. His daughters, friends, grandchildren, great-grandchildren and ancestors to this day have worked to try and gain him a prominent place in railway history. -

Capita Hartshead

News Other useful addresses CAPITA HARTSHEAD The PCSPS Governance Group Cabinet Office Civil Service Pensioners’ Alliance The Cabinet Office have set up a Governance Group to consider and advise on Grosvenor House, Basingview, First Floor Civil Service Pensions a range of issues including administration standards. The Group members are Basingstoke, Hampshire, 102 – 104 Park Lane, Croydon Dear Pensioner drawn from both employers and Trade Unions. Where the Group consider RG21 4HG CR0 1JB matters of interest that may be of interest to pensioners, it invites the Civil www.civilservice.gov.uk/pensions Telephone: 020 8688 8418 Service Pensioners Alliance to attend. Email: [email protected] Important information about your pension: April 2009 Civil Service Retirement Fellowship www.cspa.co.uk Information Suite 2, 80A Blackheath Road, This letter contains important information and news about your Civil Service London, SE10 8DA Civil Service Benevolent Fund, pension, including sections on things you need to tell us about. What to do if things go wrong Telephone: 020 8691 7411 Fund House, We treat complaints with urgency and do our utmost to put things right as Email: [email protected] 5 Anne Boleyn’s Walk, Cheam, In this letter when we refer to classic this means the pension scheme that quickly as possible. If you do have problems with the payment of your pension www.csrf.org.uk Sutton, applied to everyone who left employment before 1 October 2002. Staff in post please write to Capita’s Customer Services Manager at the PO Box 215 SM3 8DY on 30 September 2002 could opt to stay in classic or transfer to the premium address setting out your concerns.