Czech Music 2008

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Thomas D. Svatos and Twentieth-Century Czech Critical Culture

ex tempore A Journal of Compositional and Theoretical Research in Music Vol. XIV/2, Spring / Summer 2009 _________________________ A Clash over Julietta: the Martinů/Nejedlý Political Conflict - Thomas D. Svatos and Twentieth-Century Czech Critical Culture Dialectic in Miniature: Arnold Schoenberg‟s - Matthew Greenbaum Sechs Kleine Klavierstücke Opus 19 Stravinsky's Bayka (1915-16): Prose or Poetry? - Marina Lupishko Pitch Structures in Reginald Smith Brindle’s -Sundar Subramanian El Polifemo de Oro Rhythmic Cells and Organic Development: - Jean-Louis Leleu The Function of Harmonic Fields in Movement IIIb of Livre pour quatuor by Pierre Boulez Analytical Diptych: Boulez Anthèmes / Berio Sequenza XI - John MacKay co-editors: George Arasimowicz, California State University, Dominguez Hills John MacKay, West Springfield, MA associate editors: Per Broman, Bowling Green University Jeffrey Brukman, Rhodes University, RSA John Cole, Elisabeth University of Music, JAP Angela Ida de Benedictis, University of Pavia, IT Paolo Dal Molin, Université Paul Verlaine de Metz, FR Alfred Fisher, Queen‟s University, CAN Cynthia Folio, Temple University Gerry Gabel, Texas Christian University Tomas Henriques, Universidade Nova de Lisboa, POR Timothy Johnson, Ithaca College David Lidov, York University, CAN Marina Lupishko, le Havre, FRA Eva Mantzourani, Canterbury Christchurch Univ, UK Christoph Neidhöfer, McGill University, CAN Paul Paccione, Western Illinois University Robert Rollin, Youngstown State University Roger Savage, UCLA Stuart Smith, University of Maryland Thomas Svatos, Eastern Mediterranean Univ, TRNC André Villeneuve UQAM, CAN Svatos/A Clash over Julietta 1 A Clash over Julietta: The Martinů/Nejedlý Political Conflict and Twentieth-Century Czech Critical Culture Thomas D. Svatos We know and honor our Smetana, but that he must have been a Bolshevik, this is a bit out of hand. -

BMN 2001/3.Indd

Bohuslav Martinů September – December 2001 40 Years with the Name Martinů Martinů in a Different Light Martinů Events Martinů and his Homes in Nice Today News Boston’s Martinů on Tour Where Martinů is at Home Third issue The International Bohuslav Martinů Society The Bohuslav Martinů Institute CONTENTS WELCOME Karel Van Eycken ................................................. 3 40 YEARS WITH THE NAME MARTINŮ The Bohuslav Martinů Piano Quartet will Celebrate a Major Anniversary Next Season Emil Leichner ......................................................4 A BLUE DOMAIN Stuart Wilson ......................................................5 MARTINŮ EVENTS 2001 ........................6 - 8 BOSTON’S MARTINŮ ON TOUR Gregory Terian .................................................... 7 MEMBERS’ DIARY ................................................ 8 ANNOUNCEMENT Gramophone Award for Magdalena Kožená ............... 8 MARTINŮ IN A DIFFERENT LIGHT The Musical Film for Television as a Form of Interpreting Chamber Stage Works by Bohuslav Martinů Jiří Nekvasil ....................................................... 9 MARTINŮ AND HIS HOMES IN NICE TODAY Karel Van Eycken and Marcel J. Schneider ................12 FROM GREG TERIAN’S MARTINŮ REVIEW in The Dvořák Society Newsletter ...........................13 NEWS ............................................... 14 - 15 DUOS AND TRIO FOR STRINGS Review Sandra Bergmannová ..........................................15 BOHUSLAV MARTINŮ’S CORRESPONDENCE IN THE MUSEUM OF NATIONAL LITERATURE IN PRAGUE Kateřina -

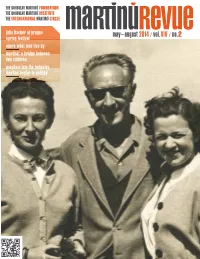

May–August 2014/ Vol.XIV / No.2

THE BOHUSLAV MARTINŮ FOUNDATION THE BOHUSLAV MARTINŮ INSTITUTE THE INTERNATIONAL MARTINŮ CIRCLE MR julia fischer at prague may–august 2014 / vol.XIV / no.2 spring festival opera what men live by martinů: a bridge between two cultures peephole into the bohuslav martinů center in polička BOHUSLAVMARTINŮ INTHEYEAR OFCZECH MUSIC & BOHUSLAVMARTINŮ DAYS contents 2014 3 PROLOGUE 4 14+15+16 SEPTEMBER 2014 9.00 pm . Lesser Town of Prague Cemetery 5 Eva Blažíčková – choreographer MARTINŮ . The Bouquet of Flowers, H 260 6 7 OCTOBER 2014 . 8.30 pm . HAMU, Martinů Hall, Prague BOHUSLAV MARTINŮ’S SOLDIER Concert in the occasion of 100th anniversary of Josef Páleníček’s birth Smetana Trio, Wenzel Grund – clarinet AND DANCER MARTINŮ . Piano Trio No 2, H 327 OLGA JANÁČKOVÁ (+ PÁLENÍČEK, JANÁČEK) THE SOLDIER AND THE DANCER IN PLZEŇ 2 NOVEMBER 2014 . 7.00 pm . National Theatre, Prague EVA VELICKÁ Ballet ensemble of the National Moravian-Silesian Theatre, Nataša Novotná – choreographer 8 MARTINŮ . The Strangler, H 314 (+ SMETANA, JANÁČEK) GEOFF PIPER MARTINA FIALKOVÁ 2 DECEMBER 2014 . 5.00 pm . Hall of Prague Conservatory Concert Marking the 40th Anniversary of the Dvořák Society for Czech and Slovak Music – programme see page 3 10 JULIA FISCHER AT PRAGUE SPRING BOHUSLAV . MARTINU DAYS FESTIVAL FRANK KUZNIK 30 NOVEMBER 2014 . 7.00 pm . HAMU, Martinů Hall, Prague TWO STARS ENCHANT THE RUDOLFINUM Concert of the winners of Bohuslav Martinů Competition PRAVOSLAV KOHOUT in the Category Piano Trio and String Quartet 2 DECEMBER 2014 . 7.30 pm . HAMU, Martinů Hall, Prague 12 Kühn Children's Choir, choirmasters: Jiří Chvála, Petr Louženský WHAT MEN LIVE BY Panocha Quartet members (Jiří Panocha, Pavel Zejfart – violin, GREGORY TERIAN Miroslav Sehnoutka – viola), Jan Kalfus – organ, Petr Kostka – recitation, Ivan Kusnjer – baritone, Daniel Wiesner – piano MARTINŮ . -

BOHUSLAV MARTINŮ JAROSLAV MIHULE / 2008 František Martinů, Colored Drawing from a Scrapbook

A POCKET GUIDE TO THE LIFE AND WORK OF BOHUSLAV MARTINŮ JAROSLAV MIHULE / 2008 František Martinů, colored drawing from a scrapbook 1 FROM POLIČKA TO PRAGUE 1890 — 1922 2 On The Polička Tower 1.1 Bohuslav came into the world in a tiny room on the gallery of the church tower where his father, Ferdinand Martinů, apart from being a shoemaker, also carried out a unique job as the tower- keeper, bell-ringer and watchman. Polička - St. James´ Church and the Bastion “On December 8th, the crow brought us a male, a boy, and on Dec. 14th 1.2 A Loving Family he was baptized as It was the mother who energetically took charge of the whole family. She was Bohuslav Jan.” the paragon of order and discipline: strict, pious – a Roman Catholic, naturally, as (The composer’s father were most inhabitants of this hilly region. made this entry in the Of course, she loved all of her children. With Ferdinand Martinů she had fi ve; and family chronicle.) the youngest and probably the most coddled was Bohuslav, born to the accom- paniment of the festive ringing of all the bells, as the town celebrated on that day the holiday of the Immaculate Conception of the Virgin Mary. To be born high above the ground, almost within the reach of the sky, seemed in itself to promise an exceptional life ahead. Also his brother František and his sister Marie had their own special talents. František graduated from art school and made use of his artistic skills above all 3 as a restorer and conservator of church art objects in his homeland as well as abroad. -

Newsletter 2-2005

THE BOHUSLAV MARTINŮ FOUNDATION & THE BOHUSLAV MARTINŮ INSTITUTE MAY—AUGUST 2005 The Greek Passion / VOL. Finally in Greece V / NO. Interview with Neeme Järvi 2 Martinů & Hans Kindler The Final Years ofthe Life of Bohuslav Martinů Antonín Tučapský on Martinů NEWS & EVENTS ts– Conten VOL. V / NO.2 MAY—AUGUST 2005 Bohuslav Martinů in Liestal, May 1956 > Photo from Max Kellerhals’archive e WelcomE —EDITORIAL —REPORT OF MAY SYMPOSIUM OF EDITORIAL BOARD —INTERNATIONAL MARTINŮ CIRCLE r Reviews —BBC SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA —CD REVIEWS —GILGAMESH y Reviews f Research THE GREEK PASSION THE FINAL YEARS OF THE FINALLY IN GREECE LIFE OF BOHUSLAV MARTINŮ • ALEŠ BŘEZINA • LUCIE BERNÁ u Interview j Memoirs WITH… NEEME JÄRVI ANTONÍN TUČAPSKÝ • EVA VELICKÁ ON MARTINŮ i Research k Events MARTINŮ & HANS KINDLER —CONCERTS • F. JAMES RYBKA & BORIS I. RYBKA —BALLETS —FESTIVALS a Memoirs l News MEMORIES OF —THE MARTINŮ INSTITUTE’S CORNER MONSIEUR MARTINŮ —NEW RECORDING —OBITUARIES • ADRIAN SCHÜRCH —BOHUSLAV MARTINŮ DISCUSSION GROUP me– b Welco THE BOHUSLAV MARTINŮ REPORT ON THE MAY SYMPOSIUM OF THE EDITORIAL NEWSLETTER is published by the Bohuslav Martinů EDITORIAL BOARD Foundation in collaboration with the DEAR READERS, Bohuslav Martinů Institute in Prague THE MEETING of the editorial board in 2005 was held on 14–15 May in the premises we are happy to present the new face of the Bohuslav Martinů Institute. It was attended by the chair of the editorial board of the Bohuslav Martinů Newsletter, EDITORS Aleš Březina as well as Sandra Bergmannová of the Charles University Institute of published by the Bohuslav Martinů Zoja Seyčková Musicology and the Bohuslav Martinů Institute, Dietrich Berke, Klaus Döge of the Foundation and Institute.We hope you Jindra Jilečková Richard Wagner-Gesamtausgabe, Jarmila Gabrielová of the Charles University Institute will enjoy the new graphical look. -

Musicologica Olomucensia 18

ACTA UNIVERSITATIS PALACKIANAE OLOMUCENSIS FACULTAS PHILOSOPHICA PHILOSOPHICA – AESTHETICA 42 – 2013 MUSICOLOGICA OLOMUCENSIA 18 Universitas Palackiana Olomucensis 2013 Musicologica Olomucensia Editor-in-chief: Lenka Křupková Editorial Board: Michael Beckerman – New York University, NY; Mikuláš Bek – Masaryk University, Brno; Roman Dykast – Academy of Performing Arts, Prague; Jarmila Gabrielová – Charles University, Prague; Lubomír Chalupka – Komenský University, Bratislava; Dieter Torke- witz – Universität für Musik und darstellende Kunst, Wien; Jan Vičar – Palacký University, Olomouc Executive editor of Volume 18 (December 2013): Markéta Koutná This volume was published in 2013 under the project of the Ministry of Education – “Excellence in Education: Improvements in publishing opportunities for academic staff in arts and humanities at the Philosophical Faculty, Palacký University, Olomouc”. The scholarly journal Musicologica Olomucensia has been published twice a year (in June and December) since 2010 and follows up on the Palacký University proceedings Acta Universitatis Palackianae Olomucensis – Musicologica Olomucensia (founded in 1993) and Kritické edice hudebních památek [Critical Editions of Musical Documents] (founded in 1996). Journal Musicologica Olomucensia can be found on EBSCOhost databases. The present volume was submitted to print on October 30, 2013. Dieser Band wurde am 30. Oktober 2013 in Druck gegeben. Předáno do tisku 30. října 2013. [email protected] www.musicologicaolomucensia.upol.cz ISSN 1212-1193 -

Bulletin 137.Vp

FRMS BULLETIN Autumn 2002 No. 137 Ed i tor: CONTENTS Ar thur Baker All Ed i to rial copy to him at: page STRATFORD 4 Ramsdale Road, NEWS Bramhall, Stockport, Week end intro 26 Cheshire SK7 2QA Com mit tee shakeup 2 Re cord ings of year 27 Tel: 0161 440 8746 Tony Baines 2 Dr John Ev ans 28 [email protected] New Cen tral Re gion 3 Belshazzar’ feast 28 Asst. Ed i tor: Philip Ashton 3 Sir William Walton 28 Reg William son (see back FRMS and you 4 Tech ni cal Fo rum 28 page for ad dress). Sibelius re cord ings 5 Coull Quar tet 29 Ed i to rial dead lines: Next years ‘Week end’ 6 Blowing in the wind 29 Spring is sue - 31st Decem ber Hungariton Records 7 Au tumn is sue - 30th June Danesborough Chorus 7 Scotland Mar keting Man ager: Scot tish Group 30 Ca thy Con nolly (see back LETTERS page). Ad ver tise ments are THE REGIONS avail able from £35.00, de - The Old Days 8 tails from her. Increases in subs. 9 Sus sex Re gion 31 Financial mat ters 10 York shire Re gion 33 Copies are distributed to all Rail ways in mu sic 10 Federation affiliates with THE SOCIETIES additional copies through FEATURES society secretaries. Estimated Hinckley 36 readership is well over 10,000. Mar tinu: his life & works 11 Put ney Mu sic 36 Individual Subscriptions are Martinu: recom. re cord ings 15 Rochdale 37 available at £6.80 for four Overtures and encores 17 Stafford 37 issues. -

September—December 2017 / Vol.XVII / No.3

THE BOHUSLAVMARTINŮ FOUNDATION THE BOHUSLAVMARTINŮ INSTITUTE THE INTERNATIONALMARTINŮCIRCLE MR the first production of september—december 2017 / vol.XVII / no.3 the greek passion, H 372/I in russia martinů & hrůša at bbc proms 2017 string quartets nos 4–7: new publication of bmce obituary: zuzana růžičková nts ---- new CDs cont Small storms. A Collection of Short Pieces by Bohuslav Martinů 3 highlights Meredith Blecha-Wells (Cello), Sun Min Kim (Piano) obituary Variations on Theme of Rossini, H 290 Ariette for Cello and Piano, H 188 B prof. václav riedlbauch Seven Arabesques for Cello and Piano, H 201 Suite Miniature for Cello and Piano, H 192 4 news Nocturnes for Cello and Piano, H 189 Variations on a Slovakian Theme, H 378 the first production of bohuslav Navona Records, 2017 martinů’s opera the greek passion, H 372/I in russia Martinů/Řezníček/Fiala Martinů: Mount of three Lights, H 349 5 imc news Hymn to St.James, H 347 Czech Philharmonic Choir Brno, Petr Fiala (Conductor) and soloists 6 imc reviews ArcoDiva, 217, TT:67:41 jakub hrůša’s debut with martinů Milhaud/Martinů: at bbc proms 2017 Complete Works for String Trio Martinů: String Trio No.1, H 136 8 imc meeting in london String Trio No.2, H 238 Jacques Thibaud String Trio: Burkhard Maiss (Violin), Hannah Strijbos (Viola), 10 obituary Bogdan Jianu (Cello) zuzana růžičková Audite 97.727, 2017, TT: 58:16 Bohuslav Martinů: Complete Works 12 interview for Cello and Orchestra …with jan edlman, anthony Concerto for Cello and Orchestra No.1, H 196 wilkinson & brian large on Concerto for -

An Overview of Bohuslav Martinů‟S Piano Style with a Guide to Analysis and Interpretation of the Fantasie Et Toccata, H

An Overview of Bohuslav Martinů‟s Piano Style with a Guide to Analysis and Interpretation of the Fantasie et Toccata, H. 281 by Jennifer Crane-Waleczek A Research Paper Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Musical Arts Approved November 2011 by the Graduate Supervisory Committee: Robert Hamilton, Chair Andrew Campbell Glenn Hackbarth Kay Norton Janice Meyer Thompson ARIZONA STATE UNIVERSITY December 2011 ABSTRACT Bohuslav Martinů (1890-1959) was a prolific composer who wrote nearly 100 works for piano. His highly imaginative and eclectic style blends elements of the Baroque, Impressionism, Twentieth-century idioms and Czech folk music. His music is fresh and appealing to the listener, yet it remains intriguing as to how all the elements are combined in a cohesive manner. Martinů himself provides clues to his compositional process. He believed in pure musical expression and the intensity of the musical idea, without the need for extra-musical or programmatic connotations. He espoused holistic and organic views toward musical perception and composition, at times referring to a work as an “organism.” This study examines Martinů‟s piano style in light of his many diverse influences and personal philosophy. The first portion of this paper discusses Martinů‟s overall style through several piano miniatures written throughout his career. It takes into consideration the composer‟s personal background, musical influences and aesthetic convictions. The second portion focuses specifically on Martinů‟s first large-scale work for piano, the Fantasie et Toccata, H. 281. Written during a time in which Martinů was black-listed by the Nazis and forced to flee Europe, this piece bears witness to the chaotic events of WWII through its complexity and intensity of character. -

Czech Music Brozura.Pdf

CZECH MUSIC Theatre Institute 1 The publication was produced in cooperation with the Music Information Centre as a part of the program Czech Music 2004 Editor in chief: Lenka Dohnalová (Theatre Institute) Editorial team: L.Dohnalová, J. Bajgar, J. Bajgarová, J. Javůrek, H. Klabanová, J. Ludvová, A. Opekar, S. Santarová, I. Šmíd Translation © 2004 by Anna Bryson Cover © 2004 by Ditta Jiříčková Book design © 2004 by Ondřej Sládek © 2005 by Theatre Institute, Celetná 17, 110 00 Prague 1, Czech Republic First printing ISBN 80-7008-175-9 All rights of this publication reserved. 2 CONTENTS CALENDER 4 MIDDLE AGE (CA 850 - CA 1440) /Jaromír Černý 11 THE RENAISSANCE (CA 1440 - CA 1620) /Jaromír Černý 14 THE BAROQUE (CA 1620 - CA 1740) /Václav Kapsa 16 BOHEMIAN LANDS AND CLASSICAL STYLE IN MUSIC (CA 1740 - CA 1820) /Tomáš Slavický 20 FIRST HALF OF THE 19TH CENTURY /Jarmila Gabrielová 24 THE PERIOD AFTER 1860 /Jarmila Gabrielová 26 THE TURN OF THE CENTURY AND THE FIRST DECADES OF THE 20TH CENTURY /Jarmila Gabrielová 32 CZECH MUSIC FROM 1945 TO THE PRESENT /Tereza Havelková 38 THE HISTORY OF CZECH OPERA /Alena Jakubcová, Josef Herman 48 THE HISTORY OF CZECH CHAMBER ENSEMBLES /Jindřich Bajgar 59 THE HISTORY OF CZECH ORCHESTRAS AND CHOIRS /Lenka Dohnalová 62 FOLK MUSIC OF BOHEMIA AND MORAVIA /Matěj Kratochvíl 66 CZECH POPULAR MUSIC /Aleš Opekar 70 NON-PROFESSIONAL MUSICAL ACTIVITIES /Lenka Lázňovská 77 FESTIVALS IN CZECH REPUBLIC /Lenka Dohnalová 79 LINKS /Lenka Dohnalová 82 3 CALENDAR ca 800 emergence of a number of principalities on Bohemian territory and the beginnings of the Great Moravian state 863-885 the mission of Constantine and Methodius sent from Byzantium; they who create a Slav liturgy in Great Moravia ca 880 the Czech prince Bořivoj (+perhaps 890/891) accepts Christianity 906 fall of Great Moravia 935 murder of Prince Wenceslas, later canonised; establishment of a unified Czech state in the reign of Boleslav I. -

10 February 2017 Page 1 of 10

Radio 3 Listings for 4 – 10 February 2017 Page 1 of 10 SATURDAY 04 FEBRUARY 2017 Martin Handley presents Radio 3©s classical breakfast show, Seong-Jin Cho (piano) featuring listener requests. FREDERICK CHOPIN INSTITUTE NIFCCD625 (CD) SAT 01:00 Through the Night (b08c340s) Igor Levitt plays Tchaikovsky and Shostakovich Email [email protected]. Chopin: Piano Concerto No. 1 and Ballades CHOPIN: Piano Concerto No. 1 in E minor Op. 11; Ballades Nos. Jonathan Swain presents a performance from pianist Igor Levit of SAT 09:00 Record Review (b08cgvlm) 1-4 Tchaikovsky©s The Seasons and Shostakovich©s 24 Preludes. Andrew McGregor with Ben Walton and Anna Picard London Symphony Orchestra, Gianandrea Noseda (conductor), 1:01 AM Seong-Jin Cho (piano) Tchaikovsky, Pyotr Ilyich [1840-1893] Andrew McGregor and guests review the best recordings of DG 94795941 (CD) The Seasons Op 37b classical music. Igor Levit (piano) Chopin: Piano Sonata No. 2 and other works 1:44 AM 9am CHOPIN: Piano Sonata No. 2 in B flat minor Op. 35 ©Marche Shostakovich, Dmitri [1906-1975] Telemann, Corelli & Bach: Chamber Music funebre©; Mazurkas (4) Op. 17; Scherzo No. 1 in B minor Op. 20 24 Preludes Op 34 BACH, J S: Keyboard Concerto No. 6 in F major, BWV1057 Aimi Kobayashi (piano) Igor Levit (piano) CORELLI: Concerto grosso Op. 6 No. 8 in G minor ©fatto per la FREDERICK CHOPIN INSTITUTE NIFCCD626 (CD) 2:20 AM notte di Natale©; Concerto grosso Op. 6 No. 4 in D major Martinu, Bohuslav [1890-1959] TELEMANN: Overture (Suite) TWV 55:C3 in C major for wind, Chopin: Les Etats D©ame Symphony No 1 strings & b.c. -

2Nd SHOWCASE of YOUNG CZECH MUSIC PERFORMERS 2018 15.-16.6

2nd SHOWCASE OF YOUNG CZECH MUSIC PERFORMERS 2018 15.-16.6. 2018, Janáček Conservatory in Ostrava INSTRUMENTALISTS HEJHALOVÁ ELIŠKA - flute (*1999) She was encouraged to deal with music by her grandfather J. Kopáček – the clarinetist and the emeritus member of Czech Philharmonic. She won the first prize in the international competition Novohradská flétna/Nové Hrady Flute 2011 and has received many prizes in international competitions. In 2011 – 2015, she was the first flutist of the Europera international symphonic orchestra. In 2016, she performed with Czech Philharmonic in Rudolfinum, Prague with conductor J. Bělohlávek. In 2017, she played at concerts of the Concertina Praga competition winners (the concerts were recorded by Czech Radio Vltava). She is going to graduate at Roudnice nad Labem grammar school under Jaroslav Pelikán, the first flutist of the National Theatre. In September 2018, she is going to study at Music Academy in Prague. Showcase program: J. S. Bach: Partita in A minor G. Enescu: Cantabile et Presto Contact: [email protected] PAŠKOVÁ KATEŘINA – clarinet (*1996) During her studies at the Janáček Conservatory in Ostrava under P. Bohuš, she was successful in the competitions Mládí/Youth and Bohuslav Martinů in Polička (2013, 2014 with the award for the music performance and interpretation of Martinů’s work). She was successful at Jastrzebie (2016) and Pro Bohemia competitions (2017), she also received the Bohuslav Martinů Foundation Award. She works with distinctive artists, such as pianist I. Kahánek, members of Smetana Trio, clarinetist K. Dohnal, cellist J. Hanousek, Moravian Philharmonic Orchestra Olomouc, Janáček Philharmonic Ostrava (2018). She drew attention to herself with her recital at the International Competition and Music Festival Beethoven Hradec and was propounded to participate in two concerts at Leoš Janáček International Music Festival (formerly Janáček May).