Thomas D. Svatos and Twentieth-Century Czech Critical Culture

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Our Newly Designed Website We Are Happy to Announce That the Twin Cities Opera Guild Has a New Website That Can Now Be Accessed on Your Phone

Celebrating 69 Years of Opera Education for Children Summer 2021 Newsletter 2021 Spring Benefit to Fund Music Education for Children Enjoy A Virtual Celebration – A Video from Fargo Moorhead Opera Young Artists August 24, 2021 Interlachen Country Club • Edina Featuring Alyssa Anderson, Mezzo Soprano Justin Spenner, Baritone Julian Ward, Pianist Our Newly Designed Website We are happy to announce that the Twin Cities Opera Guild has a new website that can now be accessed on your phone. Check us out at: www.twincitiesoperaguild.org on your computer or phone Letter from the President of TCOG It looks like we made it! We are Country Club and the delicious miso sea bass, so we at the end of the tunnel, and it are holding our fun Party in Pink, with sea bass, at looks bright and sunny. All of us Interlachen on August 24. I am so looking forward to suffered in many ways – illness, hearing opera in person again! Details are elsewhere grief, loneliness. Getting my in this newsletter. I hope everyone can come! Our Big Welcome Back Party vaccine in February was the best This is my last letter as President. I have enjoyed thing imaginable, I could reenter meeting you all, our events, and projects. Twin Cities the world. Opera Guild is in fine shape, and our new President, TCOG decided to wait a bit before resuming our Kathryn Keefer, has a long history with TCOG and events, to give folks time to get vaccinated and adjust will do a wonderful job. I hope to see you all at our to the new maskless world. -

Teaching Post-Tonal Music to Twenty-First- Century Students Author(S): Miguel A

Department of Music Theory, Jacobs School of Music, Indiana University A Pedagogical and Psychological Challenge: Teaching Post-Tonal Music to Twenty-First- Century Students Author(s): Miguel A. Roig-Francolí Source: Indiana Theory Review, Vol. 33, No. 1-2 (Summer 2017), pp. 36-68 Published by: Indiana University Press on behalf of the Department of Music Theory, Jacobs School of Music, Indiana University Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.2979/inditheorevi.33.1-2.02 Accessed: 03-09-2018 01:27 UTC JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at https://about.jstor.org/terms Indiana University Press, Department of Music Theory, Jacobs School of Music, Indiana University are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Indiana Theory Review This content downloaded from 129.74.250.206 on Mon, 03 Sep 2018 01:27:00 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms A Pedagogical and Psychological Challenge: Teaching Post-Tonal Music to Twenty-First-Century Students Miguel A. Roig-Francolí University of Cincinnati ost-tonal music has a pr problem among young musicians, and many not-so-young ones. Anyone who has recently taught a course on the theory and analysis of post-tonal music to a general Pmusic student population mostly made up of performers, be it at the undergraduate or master’s level, will probably immediately understand what the title of this article refers to. -

How Teachers Cope with Social and Educational Transformation

How Teachers Cope with Social and Educational Transformation Struggling with Multicultural Education in the Czech Classroom Dana Moree EMAN 2008 How Teachers Cope with Social and Educational Transformation Struggling with Multicultural Education in the Czech Classroom Hoe docenten omgaan met sociale en educatieve veranderingen met een samenvatting in het Nederlands Proefschrift ter verkrijging van de graad van doctor aan de Universiteit voor Humanistiek te Utrecht op gezag van de Rector, prof. dr. Hans Alma ingevolge het besluit van het College van Hoogleraren in het openbaar te verdedigen op 24 november 2008 des voormiddags te 10.30 uur door Dana Moree Geboren op 20 November 1974 te Praag PROMOTORES: Prof.dr. Wiel Veugelers Universiteit voor Humanistiek Prof.dr. Jan Sokol Charles University Praag Co-promotor: Dr. Cees Klaassen Radboud Universiteit Nijmegen BEOORDELINGSCOMMISSIE: Prof. dr. Chris Gaine University of Chichester Prof.dr. Ivor Goodson University of Bristol Prof. dr. Douwe van Houten Universiteit voor Humanistiek Dr. Yvonne Leeman Universiteit van Amsterdam Dr. Petra Zhřívalová Charles University Praag This thesis was supported by the projects: The Anthropology of Communication and Human Adaptation (MSM 0021620843) and Czechkid – Multiculturalism in the Eyes of Children. for Peter, Frank and Sebastian EMAN, Husova 656, 256 01 Benešov http://eman.evangnet.cz Dana Moree HOW TEACHERS COPE WITH SOCIAL AND EDUCATIONAL TRANSFORMATION Struggling with Multicultural Education in the Czech Classroom First edition, Benešov 2008 © Dana Moree 2008 Typhography: Petr Kadlec Coverlayout: Hana Kolbe ISBN 978-80-86211-62-6 7 Contents Acknowledgements . 9 Introduction . 10 Chapter 1 – Transformation of the cultural composition of the Czech Republic . 15 Introduction . -

The Bach Variations: a Philharmonic Festival March 6–April 6, 2013

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE February 20, 2013 Contact: Katherine E. Johnson (212) 875-5718; [email protected] THE BACH VARIATIONS: A PHILHARMONIC FESTIVAL MARCH 6–APRIL 6, 2013 PROGRAM II OF IV Alan Gilbert To Conduct Mass in B minor With Soprano Dorothea Röschmann, Mezzo-Soprano Anne Sofie von Otter, Tenor Steve Davislim, and Bass-Baritone Eric Owens with the New York Choral Artists March 13–16 The New York Philharmonic will present The Bach Variations: A Philharmonic Festival March 6–April 6, 2013. On the festival’s second orchestral program, Alan Gilbert will conduct the Philharmonic in Bach’s Mass in B minor, with soprano Dorothea Röschmann, mezzo-soprano Anne Sofie von Otter, tenor Steve Davislim, bass-baritone Eric Owens, and the New York Choral Artists, Joseph Flummerfelt, director, Wednesday, March 13, 2013, at 7:30 p.m.; Thursday, March 14 at 7:30 p.m.; Friday, March 15 at 8:00 p.m.; and Saturday, March 16 at 8:00 p.m. “The Mass in B minor is a consummate masterpiece that makes me feel humble as a musician when I hear it,” Alan Gilbert said. “Bach took a liturgical, religious starting point and made it even more universal. No matter what you believe, no matter your religious credo, or whether or not you even have a religious credo, it is impossible not to be incredibly moved by this music because it speaks from one human being directly into the heart of another. I feel very privileged to be able to touch this music.” The Bach Variations marks the first time the New York Philharmonic has presented a festival of the music of the Baroque master. -

General Index

Cambridge University Press 0521780098 - The Cambridge Companion to Twentieth-Century Opera Edited by Mervyn Cooke Index More information General index Abbate, Carolyn 282 Bach, Johann Sebastian 105 Adam, Fra Salimbene de 36 Bachelet, Alfred 137 Adami, Giuseppe 36 Baden-Baden 133 Adamo, Mark 204 Bahr, Herrmann 150 Adams, John 55, 204, 246, 260–4, 289–90, Baird, Tadeusz 176 318, 330 Bala´zs, Be´la 67–8, 271 Ade`s, Thomas 228 ballad opera 107 Adlington, Robert 218, 219 Baragwanath, Nicholas 102 Adorno, Theodor 20, 80, 86, 90, 95, 105, 114, Barbaja, Domenico 308 122, 163, 231, 248, 269, 281 Barber, Samuel 57, 206, 331 Aeschylus 22, 52, 163 Barlach, Ernst 159 Albeniz, Isaac 127 Barry, Gerald 285 Aldeburgh Festival 213, 218 Barto´k, Be´la 67–72, 74, 168 Alfano, Franco 34, 139 The Wooden Prince 68 alienation technique: see Verfremdungse¤ekt Baudelaire, Charles 62, 64 Anderson, Laurie 207 Baylis, Lilian 326 Anderson, Marian 310 Bayreuth 14, 18, 21, 49, 61–2, 63, 125, 140, 212, Andriessen, Louis 233, 234–5 312, 316, 335, 337, 338 Matthew Passion 234 Bazin, Andre´ 271 Orpheus 234 Beaumarchais, Pierre-Augustin Angerer, Paul 285 Caron de 134 Annesley, Charles 322 Nozze di Figaro, Le 134 Ansermet, Ernest 80 Beck, Julian 244 Antheil, George 202–3 Beckett, Samuel 144 ‘anti-opera’ 182–6, 195, 241, 255, 257 Krapp’s Last Tape 144 Antoine, Andre´ 81 Play 245 Apollinaire, Guillaume 113, 141 Beeson, Jack 204, 206 Appia, Adolphe 22, 62, 336 Beethoven, Ludwig van 87, 96 Aquila, Serafino dall’ 41 Eroica Symphony 178 Aragon, Louis 250 Beineix, Jean-Jacques 282 Argento, Dominick 204, 207 Bekker, Paul 109 Aristotle 226 Bel Geddes, Norman 202 Arnold, Malcolm 285 Belcari, Feo 42 Artaud, Antonin 246, 251, 255 Bellini, Vincenzo 27–8, 107 Ashby, Arved 96 Benco, Silvio 33–4 Astaire, Adele 296, 299 Benda, Georg 90 Astaire, Fred 296 Benelli, Sem 35, 36 Astruc, Gabriel 125 Benjamin, Arthur 285 Auden, W. -

BMN 2001/3.Indd

Bohuslav Martinů September – December 2001 40 Years with the Name Martinů Martinů in a Different Light Martinů Events Martinů and his Homes in Nice Today News Boston’s Martinů on Tour Where Martinů is at Home Third issue The International Bohuslav Martinů Society The Bohuslav Martinů Institute CONTENTS WELCOME Karel Van Eycken ................................................. 3 40 YEARS WITH THE NAME MARTINŮ The Bohuslav Martinů Piano Quartet will Celebrate a Major Anniversary Next Season Emil Leichner ......................................................4 A BLUE DOMAIN Stuart Wilson ......................................................5 MARTINŮ EVENTS 2001 ........................6 - 8 BOSTON’S MARTINŮ ON TOUR Gregory Terian .................................................... 7 MEMBERS’ DIARY ................................................ 8 ANNOUNCEMENT Gramophone Award for Magdalena Kožená ............... 8 MARTINŮ IN A DIFFERENT LIGHT The Musical Film for Television as a Form of Interpreting Chamber Stage Works by Bohuslav Martinů Jiří Nekvasil ....................................................... 9 MARTINŮ AND HIS HOMES IN NICE TODAY Karel Van Eycken and Marcel J. Schneider ................12 FROM GREG TERIAN’S MARTINŮ REVIEW in The Dvořák Society Newsletter ...........................13 NEWS ............................................... 14 - 15 DUOS AND TRIO FOR STRINGS Review Sandra Bergmannová ..........................................15 BOHUSLAV MARTINŮ’S CORRESPONDENCE IN THE MUSEUM OF NATIONAL LITERATURE IN PRAGUE Kateřina -

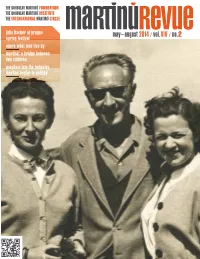

May–August 2014/ Vol.XIV / No.2

THE BOHUSLAV MARTINŮ FOUNDATION THE BOHUSLAV MARTINŮ INSTITUTE THE INTERNATIONAL MARTINŮ CIRCLE MR julia fischer at prague may–august 2014 / vol.XIV / no.2 spring festival opera what men live by martinů: a bridge between two cultures peephole into the bohuslav martinů center in polička BOHUSLAVMARTINŮ INTHEYEAR OFCZECH MUSIC & BOHUSLAVMARTINŮ DAYS contents 2014 3 PROLOGUE 4 14+15+16 SEPTEMBER 2014 9.00 pm . Lesser Town of Prague Cemetery 5 Eva Blažíčková – choreographer MARTINŮ . The Bouquet of Flowers, H 260 6 7 OCTOBER 2014 . 8.30 pm . HAMU, Martinů Hall, Prague BOHUSLAV MARTINŮ’S SOLDIER Concert in the occasion of 100th anniversary of Josef Páleníček’s birth Smetana Trio, Wenzel Grund – clarinet AND DANCER MARTINŮ . Piano Trio No 2, H 327 OLGA JANÁČKOVÁ (+ PÁLENÍČEK, JANÁČEK) THE SOLDIER AND THE DANCER IN PLZEŇ 2 NOVEMBER 2014 . 7.00 pm . National Theatre, Prague EVA VELICKÁ Ballet ensemble of the National Moravian-Silesian Theatre, Nataša Novotná – choreographer 8 MARTINŮ . The Strangler, H 314 (+ SMETANA, JANÁČEK) GEOFF PIPER MARTINA FIALKOVÁ 2 DECEMBER 2014 . 5.00 pm . Hall of Prague Conservatory Concert Marking the 40th Anniversary of the Dvořák Society for Czech and Slovak Music – programme see page 3 10 JULIA FISCHER AT PRAGUE SPRING BOHUSLAV . MARTINU DAYS FESTIVAL FRANK KUZNIK 30 NOVEMBER 2014 . 7.00 pm . HAMU, Martinů Hall, Prague TWO STARS ENCHANT THE RUDOLFINUM Concert of the winners of Bohuslav Martinů Competition PRAVOSLAV KOHOUT in the Category Piano Trio and String Quartet 2 DECEMBER 2014 . 7.30 pm . HAMU, Martinů Hall, Prague 12 Kühn Children's Choir, choirmasters: Jiří Chvála, Petr Louženský WHAT MEN LIVE BY Panocha Quartet members (Jiří Panocha, Pavel Zejfart – violin, GREGORY TERIAN Miroslav Sehnoutka – viola), Jan Kalfus – organ, Petr Kostka – recitation, Ivan Kusnjer – baritone, Daniel Wiesner – piano MARTINŮ . -

BOHUSLAV MARTINŮ JAROSLAV MIHULE / 2008 František Martinů, Colored Drawing from a Scrapbook

A POCKET GUIDE TO THE LIFE AND WORK OF BOHUSLAV MARTINŮ JAROSLAV MIHULE / 2008 František Martinů, colored drawing from a scrapbook 1 FROM POLIČKA TO PRAGUE 1890 — 1922 2 On The Polička Tower 1.1 Bohuslav came into the world in a tiny room on the gallery of the church tower where his father, Ferdinand Martinů, apart from being a shoemaker, also carried out a unique job as the tower- keeper, bell-ringer and watchman. Polička - St. James´ Church and the Bastion “On December 8th, the crow brought us a male, a boy, and on Dec. 14th 1.2 A Loving Family he was baptized as It was the mother who energetically took charge of the whole family. She was Bohuslav Jan.” the paragon of order and discipline: strict, pious – a Roman Catholic, naturally, as (The composer’s father were most inhabitants of this hilly region. made this entry in the Of course, she loved all of her children. With Ferdinand Martinů she had fi ve; and family chronicle.) the youngest and probably the most coddled was Bohuslav, born to the accom- paniment of the festive ringing of all the bells, as the town celebrated on that day the holiday of the Immaculate Conception of the Virgin Mary. To be born high above the ground, almost within the reach of the sky, seemed in itself to promise an exceptional life ahead. Also his brother František and his sister Marie had their own special talents. František graduated from art school and made use of his artistic skills above all 3 as a restorer and conservator of church art objects in his homeland as well as abroad. -

BMN 2002/2.Indd

Bohuslav Martinů May – August 2002 Always Slightly off Center An Interview with Christopher Hogwood When the Fairies Learned to Walk Feuilleton on The Three Wishes in Augsburg Second The Wonderful Flights issue It Was a Dream for Me to Have a Piece by Martinů Jiří Tancibudek and Concerto for Oboe and Small Orchestra 25 Years of the Martinů Quartet Bats in the Belfry The Film Victims and Murderers Martinů News and Events The International Bohuslav Martinů Society The Bohuslav Martinů Institute CONTENTS WELCOME Karel Van Eycken ....................................... 3 BOHUSLAV MARTINŮ SOCIETIES AROUND THE WORLD .................................. 3 ALWAYS SLIGHTLY OFF CENTER Christopher Hogwood interviewed by Aleš Březina ..................................... 4 - 6 REVIEW Sandra Bergmannová ................................. 7 WHEN THE FAIRIES LEARNED TO WALK Feuilleton on The Three Wishes in Augsburg Jörn Peter Hiekel .......................................8 BATS IN THE BELFRY The Film Victims and Murderers Patrick Lambert ........................................ 9 MARTINŮ EVENTS 2002 ........................10 - 11 THE WONDERFUL FLIGHTS Gregory Terian .........................................12 THE CZECH RHAPSODY IN A NEW GARB Adam Klemens .........................................13 25 YEARS OF THE MARTINŮ QUARTET Eva Vítová, Jana Honzíková ........................14 “MARTINŮ WAS A GREAT MUSICIAN, UNFORGETTABLE…” Announcement about Margrit Weber ............15 IT WAS A DREAM FOR ME TO HAVE A PIECE BY MARTINŮ Jiří Tancibudek and Concerto -

Newsletter 2-2005

THE BOHUSLAV MARTINŮ FOUNDATION & THE BOHUSLAV MARTINŮ INSTITUTE MAY—AUGUST 2005 The Greek Passion / VOL. Finally in Greece V / NO. Interview with Neeme Järvi 2 Martinů & Hans Kindler The Final Years ofthe Life of Bohuslav Martinů Antonín Tučapský on Martinů NEWS & EVENTS ts– Conten VOL. V / NO.2 MAY—AUGUST 2005 Bohuslav Martinů in Liestal, May 1956 > Photo from Max Kellerhals’archive e WelcomE —EDITORIAL —REPORT OF MAY SYMPOSIUM OF EDITORIAL BOARD —INTERNATIONAL MARTINŮ CIRCLE r Reviews —BBC SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA —CD REVIEWS —GILGAMESH y Reviews f Research THE GREEK PASSION THE FINAL YEARS OF THE FINALLY IN GREECE LIFE OF BOHUSLAV MARTINŮ • ALEŠ BŘEZINA • LUCIE BERNÁ u Interview j Memoirs WITH… NEEME JÄRVI ANTONÍN TUČAPSKÝ • EVA VELICKÁ ON MARTINŮ i Research k Events MARTINŮ & HANS KINDLER —CONCERTS • F. JAMES RYBKA & BORIS I. RYBKA —BALLETS —FESTIVALS a Memoirs l News MEMORIES OF —THE MARTINŮ INSTITUTE’S CORNER MONSIEUR MARTINŮ —NEW RECORDING —OBITUARIES • ADRIAN SCHÜRCH —BOHUSLAV MARTINŮ DISCUSSION GROUP me– b Welco THE BOHUSLAV MARTINŮ REPORT ON THE MAY SYMPOSIUM OF THE EDITORIAL NEWSLETTER is published by the Bohuslav Martinů EDITORIAL BOARD Foundation in collaboration with the DEAR READERS, Bohuslav Martinů Institute in Prague THE MEETING of the editorial board in 2005 was held on 14–15 May in the premises we are happy to present the new face of the Bohuslav Martinů Institute. It was attended by the chair of the editorial board of the Bohuslav Martinů Newsletter, EDITORS Aleš Březina as well as Sandra Bergmannová of the Charles University Institute of published by the Bohuslav Martinů Zoja Seyčková Musicology and the Bohuslav Martinů Institute, Dietrich Berke, Klaus Döge of the Foundation and Institute.We hope you Jindra Jilečková Richard Wagner-Gesamtausgabe, Jarmila Gabrielová of the Charles University Institute will enjoy the new graphical look. -

Musicologica Olomucensia 18

ACTA UNIVERSITATIS PALACKIANAE OLOMUCENSIS FACULTAS PHILOSOPHICA PHILOSOPHICA – AESTHETICA 42 – 2013 MUSICOLOGICA OLOMUCENSIA 18 Universitas Palackiana Olomucensis 2013 Musicologica Olomucensia Editor-in-chief: Lenka Křupková Editorial Board: Michael Beckerman – New York University, NY; Mikuláš Bek – Masaryk University, Brno; Roman Dykast – Academy of Performing Arts, Prague; Jarmila Gabrielová – Charles University, Prague; Lubomír Chalupka – Komenský University, Bratislava; Dieter Torke- witz – Universität für Musik und darstellende Kunst, Wien; Jan Vičar – Palacký University, Olomouc Executive editor of Volume 18 (December 2013): Markéta Koutná This volume was published in 2013 under the project of the Ministry of Education – “Excellence in Education: Improvements in publishing opportunities for academic staff in arts and humanities at the Philosophical Faculty, Palacký University, Olomouc”. The scholarly journal Musicologica Olomucensia has been published twice a year (in June and December) since 2010 and follows up on the Palacký University proceedings Acta Universitatis Palackianae Olomucensis – Musicologica Olomucensia (founded in 1993) and Kritické edice hudebních památek [Critical Editions of Musical Documents] (founded in 1996). Journal Musicologica Olomucensia can be found on EBSCOhost databases. The present volume was submitted to print on October 30, 2013. Dieser Band wurde am 30. Oktober 2013 in Druck gegeben. Předáno do tisku 30. října 2013. [email protected] www.musicologicaolomucensia.upol.cz ISSN 1212-1193 -

Downloaded From

BÄRENREITER URTEXT offering the best CZECHMUSIC of Czech music BÄRENREITER URTEXT is a seal of quality assigned only to scholarly-critical editions. It guarantees that the musical text represents the current state of research, prepared in accordance with clearly defined editorial guidelines. Bärenreiter Urtext: the last word in authentic text — the musicians’ choice. Your Music Dealer SPA 314 SPA SALES CATALOGUE 2021 /2022 Bärenreiter Praha • Praha Bärenreiter Bärenreiter Praha | www.baerenreiter.cz | [email protected] | www.baerenreiter.com BÄRENREITER URTEXT Other Bärenreiter Catalogues THE MUSICIAN ' S CHOICE Bärenreiter – Bärenreiter – The Programme 2019/2020 Das Programm 2018/2019 SPA 480 (Eng) SPA 478 (Ger) Bärenreiter's bestsellers for The most comprehensive piano, organ, strings, winds, catalogue for all solo chamber ensembles, and solo instruments, chamber music voice. It also lists study and and solo voice. Vocal scores orchestral scores, facsimiles and study scores are also and reprints, as well as books included. on music. Bärenreiter – Bärenreiter – Bärenreiter Music for Piano 2019/2020 Music for Organ Music for Organ 2014/2015 SPA 233 (Eng) 2014/2015 SPA 238 (Eng) Bärenreiter's complete Urtext Bärenreiter's Urtext programme for piano as well programme for organ as well as all educational titles and as collections and series. collections for solo and piano You will also find jazz works, four hands. Chamber music transcriptions, works for with piano is also listed. Your Music Dealer: organ and voice, as well as a selection of contemporary music. Bärenreiter-Verlag · 34111 Kassel · Germany · www.baerenreiter.com · SPA 238 MARTINŮ B Ä R E N R E I T E R U R T E X T Bärenreiter – Bärenreiter – Music for Strings 2018/2019 Choral Music 2018/2019 Nonet č.