OCTOBER 21, 2016 at 11 AM Cello Concerto in B Minor Amit Peled

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Exile and Acculturation: Refugee Historians Since the Second World War

ANTOON DE BAETS Exile and Acculturation: Refugee Historians since the Second World War two forms, intended and unin- tended. Within the domain of historical writing, both exist. A famous example of intended historiographical contact was the arrival B - of the German historian Ludwig Riess ( ), a student of Leopold von Ranke, in Japan. On the recommendation of the director of the bureau of historiography, Shigeno Yasutsugu, Riess began to lecture at the Im- perial University (renamed Tokyo Imperial University in ) in . He spoke about the Rankean method with its emphasis on facts and critical, document- and evidence-based history. At his suggestion, Shigeno founded the Historical Society of Japan and the Journal of Historical Scholarship. Riess influenced an entire generation of Japanese historians, including Shigeno himself and Kume Kunitake, then well known for their demystification of entire areas of Japanese history.1 However, this famous case of planned acculturation has less well-known aspects. First, Riess, who was a Jew and originally a specialist in English history, went to Japan, among other reasons, possibly on account of the anti-Semitism and Anglo- phobia characteristic of large parts of the German academy at the time. Only in did he return from Japan to become an associate professor at the University of Berlin.2 Second, Riess and other German historians (such as Ernst Bernheim, whose Lehrbuch der historischen Methode und der Geschichtsphilosophie, published in , was popular in Japan) were influ- ential only because Japanese historical methodology focused before their arrival on the explication of documents.3 Riess’s legacy had unexpected I am very grateful to Georg Iggers, Shula Marks, Natalie Nicora, Claire Boonzaaijer, and Anna Udo for their helpful criticism. -

Thomas D. Svatos and Twentieth-Century Czech Critical Culture

ex tempore A Journal of Compositional and Theoretical Research in Music Vol. XIV/2, Spring / Summer 2009 _________________________ A Clash over Julietta: the Martinů/Nejedlý Political Conflict - Thomas D. Svatos and Twentieth-Century Czech Critical Culture Dialectic in Miniature: Arnold Schoenberg‟s - Matthew Greenbaum Sechs Kleine Klavierstücke Opus 19 Stravinsky's Bayka (1915-16): Prose or Poetry? - Marina Lupishko Pitch Structures in Reginald Smith Brindle’s -Sundar Subramanian El Polifemo de Oro Rhythmic Cells and Organic Development: - Jean-Louis Leleu The Function of Harmonic Fields in Movement IIIb of Livre pour quatuor by Pierre Boulez Analytical Diptych: Boulez Anthèmes / Berio Sequenza XI - John MacKay co-editors: George Arasimowicz, California State University, Dominguez Hills John MacKay, West Springfield, MA associate editors: Per Broman, Bowling Green University Jeffrey Brukman, Rhodes University, RSA John Cole, Elisabeth University of Music, JAP Angela Ida de Benedictis, University of Pavia, IT Paolo Dal Molin, Université Paul Verlaine de Metz, FR Alfred Fisher, Queen‟s University, CAN Cynthia Folio, Temple University Gerry Gabel, Texas Christian University Tomas Henriques, Universidade Nova de Lisboa, POR Timothy Johnson, Ithaca College David Lidov, York University, CAN Marina Lupishko, le Havre, FRA Eva Mantzourani, Canterbury Christchurch Univ, UK Christoph Neidhöfer, McGill University, CAN Paul Paccione, Western Illinois University Robert Rollin, Youngstown State University Roger Savage, UCLA Stuart Smith, University of Maryland Thomas Svatos, Eastern Mediterranean Univ, TRNC André Villeneuve UQAM, CAN Svatos/A Clash over Julietta 1 A Clash over Julietta: The Martinů/Nejedlý Political Conflict and Twentieth-Century Czech Critical Culture Thomas D. Svatos We know and honor our Smetana, but that he must have been a Bolshevik, this is a bit out of hand. -

Soziologie in Österreich Nach 1945 Fleck, Christian

www.ssoar.info Soziologie in Österreich nach 1945 Fleck, Christian Veröffentlichungsversion / Published Version Sammelwerksbeitrag / collection article Zur Verfügung gestellt in Kooperation mit / provided in cooperation with: SSG Sozialwissenschaften, USB Köln Empfohlene Zitierung / Suggested Citation: Fleck, C. (1988). Soziologie in Österreich nach 1945. In C. Cobet (Hrsg.), Einführung in Fragen an die Soziologie in Deutschland nach Hitler 1945-1950 (S. 123-147). Frankfurt am Main: Cobet. https://nbn-resolving.org/urn:nbn:de:0168- ssoar-235170 Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Dieser Text wird unter einer Deposit-Lizenz (Keine This document is made available under Deposit Licence (No Weiterverbreitung - keine Bearbeitung) zur Verfügung gestellt. Redistribution - no modifications). We grant a non-exclusive, non- Gewährt wird ein nicht exklusives, nicht übertragbares, transferable, individual and limited right to using this document. persönliches und beschränktes Recht auf Nutzung dieses This document is solely intended for your personal, non- Dokuments. Dieses Dokument ist ausschließlich für commercial use. All of the copies of this documents must retain den persönlichen, nicht-kommerziellen Gebrauch bestimmt. all copyright information and other information regarding legal Auf sämtlichen Kopien dieses Dokuments müssen alle protection. You are not allowed to alter this document in any Urheberrechtshinweise und sonstigen Hinweise auf gesetzlichen way, to copy it for public or commercial purposes, to exhibit the Schutz beibehalten werden. Sie dürfen dieses Dokument document in public, to perform, distribute or otherwise use the nicht in irgendeiner Weise abändern, noch dürfen Sie document in public. dieses Dokument für öffentliche oder kommerzielle Zwecke By using this particular document, you accept the above-stated vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, aufführen, vertreiben oder conditions of use. -

Press Release

Press release Kronberg’s new study programme for pianists gets underway Kronberg Academy names first students on the “Sir András Schiff Performance Programme for Young Pianists” Mishka Rushdie Momen and Jean-Sélim Abdelmoula are to be the first students enrolled on the new study programme for pianists at Kronberg Academy. The two-year course of study entitled the “Sir András Schiff Performance Programme for Young Pianists” begins in October 2018 and is aimed at top class young pianists who wish to focus on chamber music. Sir András Schiff will, himself, teach on the programme that he has developed jointly with Kronberg Academy. The world-famous pianist and conductor has been closely associated with Kronberg Academy for many years as an artist, lecturer and member of the Artistic Council. Kirill Gerstein, Professor Ferenc Rados, Dénes Várjon and Professor Rita Wagner join Sir András Schiff as the lecturers on the new programme. The young pianists will primarily explore duets and works for chamber ensembles together with students of violin, viola and cello. Like all students at Kronberg Academy, they will also be able to take lessons in theoretical subjects and in German. The Günter Henle Foundation and the Horizon Foundation are providing substantial funding for the Sir András Schiff Performance Programme for Young Pianists. The foundations will assume the patronage for the first four years of the programme, thus covering the majority of the tuition costs for the first two students. In addition, G. Henle Verlag is kindly donating sheet music from its entire catalogue of piano repertoire, comprising 706 Urtext editions from 55 composers for solo piano and duet, including pocket scores. -

Kronberg Academy Jahrbuch 2016

Jahrbuch der Kronberg Academy Kronberg Academy‘s Yearbook Das Jahrbuch der Kronberg Academy wurde überwiegend durch Anzeigen und ehrenamltiches Engagement inanziert und ermöglicht. The Kronberg Academy Yearbook was entirely inanced and produced through advertisements and volunteer efforts. Die Kronberg Academy arbeitet und lebt für die Musik, gemeinsam mit vielen bedeutenden Künstlern. Allen voran gehen die Mitglieder ihres künstlerischen Beirats. Kronberg Academy works and lives for music, along with many leading artists – fi rst and foremost with the members of its Artistic Council Yuri Bashmet Marta Casals Istomin Gidon Kremer Sir András Schiff Mstislav Rostropovich † (bis / until 2007) Anastasia Kobekina JAHRBUCH DER KRONBERG ACADEMY 2016 INHALT 6 Editorial CELLO MEISTERKURSE 8 Beirat, Kuratorium, International Advisory Board, Stifter, Stiftungsförderer & KONZERTE 10 Fondazione Casa Musica Impressionen 94 14 Kronberg Academy Forum Lust auf Skepsis 102 Klassik Academy 108 Künstler, Werke und mehr 116 WARUM KRONBERG? VERABREDUNG MIT SLAVA 120 Warum Kronberg? 18 MIT MUSIK – MITEINANDER 126 Miriam Helms Ålien Die volle Kraft der Musik 20 Kian Soltani Wie eine Familie 22 CLASSIC FOR KIDS 132 Kaoru Oe Ideen schwirren in meinem Kopf 24 William Hagen Selbstbewusst unsere Ideen teilen 25 Wenting Kang Raum für Konzentration 26 KRONBERG ACADEMY Was 2016 sonst noch geschah 138 Neue Homepage 142 KRONBERG ACADEMY Gastfamilie sein 144 STUDIENGÄNGE Emanuel Feuermann Konservatorium 146 Freunde und Förderer der Kronberg Academy 148 Maßgeschneidert 40 -

243 Mitteilungen DEZEMBER 2019 JOSEF VOGL: AUFBRUCH in DEN OSTEN Österreichische Migranten in Sowjetisch-Kasachstan

DÖW DOKUMENTATIONSARCHIV DES ÖSTERREICHISCHEN WIDERSTANDES FOLGE 243 Mitteilungen DEZEMBER 2019 JOSEF VOGL: AUFBRUCH IN DEN OSTEN Österreichische Migranten in Sowjetisch-Kasachstan Hintergründe und Akteure der organisierten Gruppenemigration in die Sowjetrepublik Kasachstan in den 1920er-Jahren sowie die spätere stalinistische Verfolgung von Österreichern und Österreicherinnen in Kasachstan stehen im Fokus der Publikation von Josef Vogl. Der vom Dokumentationsarchiv des österreichischen Widerstandes (DÖW) herausgegebene Band mit zahlreichen Kurzbiogra- fien ist im November 2019 im mandelbaum verlag erschienen. Grundlage war ein vom Zukunftsfonds der Republik Österreich geför- dertes Projekt, das Archivarbeiten in Kasachstan ermöglichte. Josef Vogl war 1982 bis 2006 Mitarbeiter des Österreichischen Ost- und Südosteuropa-Instituts und arbeitete anschließend bis zu sei- ner Pensionierung am DÖW. Gemeinsam mit dem Historiker Barry McLoughlin veröffentlichte er 2013 die ebenfalls vom DÖW her- ausgegebene Publikation „‚... Ein Paragraf wird sich finden‘. Gedenkbuch der österreichischen Stalin-Opfer (bis 1945)“. Im März 1926 gründete eine Gruppe von mehr als 200 österreichischen Auswande- rern eine Kolonie am Fluss Syrdar’ja in Josef Vogl der Nähe von Kzyl-Orda, der damaligen Aufbruch in Hauptstadt von Kasachstan. Armut und den Osten der Mangel an Arbeitsplätzen waren die ausschlaggebenden Motive für die Emig- Österreichische ration. Die Regierung in Österreich ge- Migranten in währte finanzielle Unterstützung, um Sowjetisch- Arbeitslose und lästige Demonstranten Kasachstan loszuwerden. Die sowjetische Seite war indessen an Devisen und Agrartechnik Herausgegeben interessiert. Trotz umfangreicher Kredite vom DÖW ging die Kolonie aufgrund des unfruchtba- ren Landes und innerer Streitigkeiten be- reits 1927 zugrunde. Wien–Berlin: Archivmaterialien aus Wien, Berlin, Mos- mandelbaum kau und kasachischen Archiven erlaubten verlag 2019 es, die traurigen Schicksale der wagemuti- gen Kolonisten und ihrer Familien nach- 296 Seiten, zuzeichnen. -

BMN 2001/3.Indd

Bohuslav Martinů September – December 2001 40 Years with the Name Martinů Martinů in a Different Light Martinů Events Martinů and his Homes in Nice Today News Boston’s Martinů on Tour Where Martinů is at Home Third issue The International Bohuslav Martinů Society The Bohuslav Martinů Institute CONTENTS WELCOME Karel Van Eycken ................................................. 3 40 YEARS WITH THE NAME MARTINŮ The Bohuslav Martinů Piano Quartet will Celebrate a Major Anniversary Next Season Emil Leichner ......................................................4 A BLUE DOMAIN Stuart Wilson ......................................................5 MARTINŮ EVENTS 2001 ........................6 - 8 BOSTON’S MARTINŮ ON TOUR Gregory Terian .................................................... 7 MEMBERS’ DIARY ................................................ 8 ANNOUNCEMENT Gramophone Award for Magdalena Kožená ............... 8 MARTINŮ IN A DIFFERENT LIGHT The Musical Film for Television as a Form of Interpreting Chamber Stage Works by Bohuslav Martinů Jiří Nekvasil ....................................................... 9 MARTINŮ AND HIS HOMES IN NICE TODAY Karel Van Eycken and Marcel J. Schneider ................12 FROM GREG TERIAN’S MARTINŮ REVIEW in The Dvořák Society Newsletter ...........................13 NEWS ............................................... 14 - 15 DUOS AND TRIO FOR STRINGS Review Sandra Bergmannová ..........................................15 BOHUSLAV MARTINŮ’S CORRESPONDENCE IN THE MUSEUM OF NATIONAL LITERATURE IN PRAGUE Kateřina -

Influencersnfluencers

Professionals MA 30 The of the year IInfluencersnfluencers december 2015 1. GEOFFREY JOHN DAVIES on the cover Founder and CEO The Violin Channel 2. LEILA GETZ 4 Founder and Artistic Director 3 Vancouver Recital Society 1 5 3. JORDAN PEIMER Executive Director ArtPower!, University of CA, San Diego 2 4. MICHAEL HEASTON 10 11 Director of the Domingo-Cafritz Young 6 7 9 Artist Program & Adviser to the Artistic Director Washington National Opera Associate Artistic Director Glimmerglass Festival 15 8 5. AMIT PELED 16 Cellist and Professor Peabody Conservatory 12 6. YEHUDA GILAD 17 Music Director, The Colburn Orchestra The Colburn School 13 Professor of Clarinet 23 Colburn and USC Thornton School of Music 14 7. ROCÍO MOLINA 20 Flamenco Dance Artist 22 24 8. FRANCISCO J. NÚÑEZ 19 21 Founder and Artistic Director 18 Young People’s Chorus of New York City 26 25 9. JON LIMBACHER Managing Director and President St. Paul Chamber Orchestra 28 10. CHERYL MENDELSON Chief Operating Officer 27 Harris Theater for Music and Dance, Chicago 30 11. MEI-ANN CHEN 29 Music Director Chicago Sinfonietta and 18. UTH ELT Memphis Symphony Orchestra R F Founder and President 24. AFA SADYKHLY DWORKIN San Francisco Performances President and Artistic Director 12. DAVID KATZ Sphinx Organization Founder and Chief Judge 19. HARLOTTE EE The American Prize C L President and Founder 25. DR. TIM LAUTZENHEISER Primo Artists Vice President of Education 13. JONATHAN HERMAN Conn-Selmer Executive Director 20. OIS EITZES National Guild for Community Arts Education L R Director of Arts and Cultural Programming 26. JANET COWPERTHWAITE WABE-FM, Atlanta Managing Director 14. -

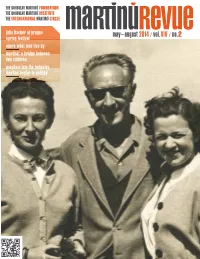

May–August 2014/ Vol.XIV / No.2

THE BOHUSLAV MARTINŮ FOUNDATION THE BOHUSLAV MARTINŮ INSTITUTE THE INTERNATIONAL MARTINŮ CIRCLE MR julia fischer at prague may–august 2014 / vol.XIV / no.2 spring festival opera what men live by martinů: a bridge between two cultures peephole into the bohuslav martinů center in polička BOHUSLAVMARTINŮ INTHEYEAR OFCZECH MUSIC & BOHUSLAVMARTINŮ DAYS contents 2014 3 PROLOGUE 4 14+15+16 SEPTEMBER 2014 9.00 pm . Lesser Town of Prague Cemetery 5 Eva Blažíčková – choreographer MARTINŮ . The Bouquet of Flowers, H 260 6 7 OCTOBER 2014 . 8.30 pm . HAMU, Martinů Hall, Prague BOHUSLAV MARTINŮ’S SOLDIER Concert in the occasion of 100th anniversary of Josef Páleníček’s birth Smetana Trio, Wenzel Grund – clarinet AND DANCER MARTINŮ . Piano Trio No 2, H 327 OLGA JANÁČKOVÁ (+ PÁLENÍČEK, JANÁČEK) THE SOLDIER AND THE DANCER IN PLZEŇ 2 NOVEMBER 2014 . 7.00 pm . National Theatre, Prague EVA VELICKÁ Ballet ensemble of the National Moravian-Silesian Theatre, Nataša Novotná – choreographer 8 MARTINŮ . The Strangler, H 314 (+ SMETANA, JANÁČEK) GEOFF PIPER MARTINA FIALKOVÁ 2 DECEMBER 2014 . 5.00 pm . Hall of Prague Conservatory Concert Marking the 40th Anniversary of the Dvořák Society for Czech and Slovak Music – programme see page 3 10 JULIA FISCHER AT PRAGUE SPRING BOHUSLAV . MARTINU DAYS FESTIVAL FRANK KUZNIK 30 NOVEMBER 2014 . 7.00 pm . HAMU, Martinů Hall, Prague TWO STARS ENCHANT THE RUDOLFINUM Concert of the winners of Bohuslav Martinů Competition PRAVOSLAV KOHOUT in the Category Piano Trio and String Quartet 2 DECEMBER 2014 . 7.30 pm . HAMU, Martinů Hall, Prague 12 Kühn Children's Choir, choirmasters: Jiří Chvála, Petr Louženský WHAT MEN LIVE BY Panocha Quartet members (Jiří Panocha, Pavel Zejfart – violin, GREGORY TERIAN Miroslav Sehnoutka – viola), Jan Kalfus – organ, Petr Kostka – recitation, Ivan Kusnjer – baritone, Daniel Wiesner – piano MARTINŮ . -

BOHUSLAV MARTINŮ JAROSLAV MIHULE / 2008 František Martinů, Colored Drawing from a Scrapbook

A POCKET GUIDE TO THE LIFE AND WORK OF BOHUSLAV MARTINŮ JAROSLAV MIHULE / 2008 František Martinů, colored drawing from a scrapbook 1 FROM POLIČKA TO PRAGUE 1890 — 1922 2 On The Polička Tower 1.1 Bohuslav came into the world in a tiny room on the gallery of the church tower where his father, Ferdinand Martinů, apart from being a shoemaker, also carried out a unique job as the tower- keeper, bell-ringer and watchman. Polička - St. James´ Church and the Bastion “On December 8th, the crow brought us a male, a boy, and on Dec. 14th 1.2 A Loving Family he was baptized as It was the mother who energetically took charge of the whole family. She was Bohuslav Jan.” the paragon of order and discipline: strict, pious – a Roman Catholic, naturally, as (The composer’s father were most inhabitants of this hilly region. made this entry in the Of course, she loved all of her children. With Ferdinand Martinů she had fi ve; and family chronicle.) the youngest and probably the most coddled was Bohuslav, born to the accom- paniment of the festive ringing of all the bells, as the town celebrated on that day the holiday of the Immaculate Conception of the Virgin Mary. To be born high above the ground, almost within the reach of the sky, seemed in itself to promise an exceptional life ahead. Also his brother František and his sister Marie had their own special talents. František graduated from art school and made use of his artistic skills above all 3 as a restorer and conservator of church art objects in his homeland as well as abroad. -

Newsletter 2-2005

THE BOHUSLAV MARTINŮ FOUNDATION & THE BOHUSLAV MARTINŮ INSTITUTE MAY—AUGUST 2005 The Greek Passion / VOL. Finally in Greece V / NO. Interview with Neeme Järvi 2 Martinů & Hans Kindler The Final Years ofthe Life of Bohuslav Martinů Antonín Tučapský on Martinů NEWS & EVENTS ts– Conten VOL. V / NO.2 MAY—AUGUST 2005 Bohuslav Martinů in Liestal, May 1956 > Photo from Max Kellerhals’archive e WelcomE —EDITORIAL —REPORT OF MAY SYMPOSIUM OF EDITORIAL BOARD —INTERNATIONAL MARTINŮ CIRCLE r Reviews —BBC SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA —CD REVIEWS —GILGAMESH y Reviews f Research THE GREEK PASSION THE FINAL YEARS OF THE FINALLY IN GREECE LIFE OF BOHUSLAV MARTINŮ • ALEŠ BŘEZINA • LUCIE BERNÁ u Interview j Memoirs WITH… NEEME JÄRVI ANTONÍN TUČAPSKÝ • EVA VELICKÁ ON MARTINŮ i Research k Events MARTINŮ & HANS KINDLER —CONCERTS • F. JAMES RYBKA & BORIS I. RYBKA —BALLETS —FESTIVALS a Memoirs l News MEMORIES OF —THE MARTINŮ INSTITUTE’S CORNER MONSIEUR MARTINŮ —NEW RECORDING —OBITUARIES • ADRIAN SCHÜRCH —BOHUSLAV MARTINŮ DISCUSSION GROUP me– b Welco THE BOHUSLAV MARTINŮ REPORT ON THE MAY SYMPOSIUM OF THE EDITORIAL NEWSLETTER is published by the Bohuslav Martinů EDITORIAL BOARD Foundation in collaboration with the DEAR READERS, Bohuslav Martinů Institute in Prague THE MEETING of the editorial board in 2005 was held on 14–15 May in the premises we are happy to present the new face of the Bohuslav Martinů Institute. It was attended by the chair of the editorial board of the Bohuslav Martinů Newsletter, EDITORS Aleš Březina as well as Sandra Bergmannová of the Charles University Institute of published by the Bohuslav Martinů Zoja Seyčková Musicology and the Bohuslav Martinů Institute, Dietrich Berke, Klaus Döge of the Foundation and Institute.We hope you Jindra Jilečková Richard Wagner-Gesamtausgabe, Jarmila Gabrielová of the Charles University Institute will enjoy the new graphical look. -

En Torno Al Maestro Pablo Casals En Puerto Rico Y La Alianza Documental Sobre Su Legado

En Torno al Maestro Pablo Casals en Puerto Rico y la Alianza Documental sobre su Legado Sofía Cánepa-Ekdahl, MIS* Con la colaboración de Luisa Vigo-Cepeda, Ph.D.** Resumen El artículo se basa en el proyecto de investigación realizado por Sofía Cánepa- Ekdahl (2005) en torno al rescate de la documentación del Maestro Pablo Casals Defilló (1876-1973), virtuoso violonchelista, compositor y director de orquesta catalán, quien residió en Puerto Rico entre 1956 y 1973. Presenta el rescate del acervo documental descriptivo realizado que conllevó a conformar una alianza en torno a su legado con 14 repositorios en Puerto Rico, tanto del sector público como privado; y describe la creación de la página Web Pablo Casals, Fondos Documentales en Puerto Rico que reúne el caudal documental. A través de la alianza se aspira a desarrollar una Comunidad de Aprendizaje y del Conocimiento virtual en torno a la vida y obra del Maestro Pablo Casals en Puerto Rico; a estimular el desarrollo efectivo de la Alianza Documental representada en la página Web, orientada a permitir que la información se comparta, sin fronteras; y a ser parte integrante de la Red Casals a nivel internacional. Descriptores Casals Defilló, Pablo (1876-1973); Alianza Documental Pablo Casals; Análisis documental; Fondos Documentales en Puerto Rico; Red Casals Introducción Pablo Casals Defilló (1876-1973), violonchelista, compositor y director de orquesta, catalán, es uno de los músicos y humanistas más prominentes del Siglo XX. Nace en Vendrell, Cataluña, hijo de Carlos Casals i Riba (1852-1908), catalán, y la puertorriqueña, Pilar Defilló i Amiguet (1853- 1931), natural de Mayagüez.