ABSTRACT Title of Dissertation: ELGAR and MART&: the CELLO WORKS and MUSICAL CHARACTERISTICS of TWO REMARKABLE, SELF-TAUGHT

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sir John Eliot Gardiner Conductor Stravinsky Symphony in Three Movements = 160 Andante—Interlude:Q L’Istesso Tempo— Con Moto Elgar in the South (Alassio), Op

Program OnE HundrEd TwEnTIETH SEASOn Chicago Symphony orchestra riccardo muti Music director Pierre Boulez Helen regenstein Conductor Emeritus Yo-Yo ma Judson and Joyce Green Creative Consultant Global Sponsor of the CSO Thursday, January 20, 2011, at 8:00 Saturday, January 22, 2011, at 8:00 Sir John Eliot gardiner Conductor Stravinsky Symphony in Three Movements = 160 Andante—Interlude:q L’istesso tempo— Con moto Elgar In the South (Alassio), Op. 50 IntErmISSIon Bartók Concerto for Orchestra Introduzione: Andante non troppo—Allegro vivace Giuoco delle coppie: Allegro scherzando Elegia: Andante non troppo Intermezzo interrotto: Allegretto Finale: Presto Steinway is the official piano of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra. This program is partially supported by grants from the Illinois Arts Council, a state agency, and the National Endowment for the Arts. CommEntS by PHILLIP HuSCHEr Igor Stravinsky Born June 18, 1882, Oranienbaum, Russia. Died April 6, 1971, New York City. Symphony in three movements o composer has given us more Stravinsky is again playing word Nperspectives on a “symphony” games. (And, perhaps, as has than Stravinsky. He wrote a sym- been suggested, he used the term phony at the very beginning of his partly to placate his publisher, who career (it’s his op. 1), but Stravinsky reminded him, after the score was quickly became famous as the finished, that he had been com- composer of three ballet scores missioned to write a symphony.) (Petrushka, The Firebird, and The Rite Then, at last, a true symphony: in of Spring), and he spent the next few 1938, Mrs. Robert Woods Bliss, years composing for the theater and together with Mrs. -

Thomas D. Svatos and Twentieth-Century Czech Critical Culture

ex tempore A Journal of Compositional and Theoretical Research in Music Vol. XIV/2, Spring / Summer 2009 _________________________ A Clash over Julietta: the Martinů/Nejedlý Political Conflict - Thomas D. Svatos and Twentieth-Century Czech Critical Culture Dialectic in Miniature: Arnold Schoenberg‟s - Matthew Greenbaum Sechs Kleine Klavierstücke Opus 19 Stravinsky's Bayka (1915-16): Prose or Poetry? - Marina Lupishko Pitch Structures in Reginald Smith Brindle’s -Sundar Subramanian El Polifemo de Oro Rhythmic Cells and Organic Development: - Jean-Louis Leleu The Function of Harmonic Fields in Movement IIIb of Livre pour quatuor by Pierre Boulez Analytical Diptych: Boulez Anthèmes / Berio Sequenza XI - John MacKay co-editors: George Arasimowicz, California State University, Dominguez Hills John MacKay, West Springfield, MA associate editors: Per Broman, Bowling Green University Jeffrey Brukman, Rhodes University, RSA John Cole, Elisabeth University of Music, JAP Angela Ida de Benedictis, University of Pavia, IT Paolo Dal Molin, Université Paul Verlaine de Metz, FR Alfred Fisher, Queen‟s University, CAN Cynthia Folio, Temple University Gerry Gabel, Texas Christian University Tomas Henriques, Universidade Nova de Lisboa, POR Timothy Johnson, Ithaca College David Lidov, York University, CAN Marina Lupishko, le Havre, FRA Eva Mantzourani, Canterbury Christchurch Univ, UK Christoph Neidhöfer, McGill University, CAN Paul Paccione, Western Illinois University Robert Rollin, Youngstown State University Roger Savage, UCLA Stuart Smith, University of Maryland Thomas Svatos, Eastern Mediterranean Univ, TRNC André Villeneuve UQAM, CAN Svatos/A Clash over Julietta 1 A Clash over Julietta: The Martinů/Nejedlý Political Conflict and Twentieth-Century Czech Critical Culture Thomas D. Svatos We know and honor our Smetana, but that he must have been a Bolshevik, this is a bit out of hand. -

BRITISH and COMMONWEALTH CONCERTOS from the NINETEENTH CENTURY to the PRESENT Sir Edward Elgar

BRITISH AND COMMONWEALTH CONCERTOS FROM THE NINETEENTH CENTURY TO THE PRESENT A Discography of CDs & LPs Prepared by Michael Herman Sir Edward Elgar (1857-1934) Born in Broadheath, Worcestershire, Elgar was the son of a music shop owner and received only private musical instruction. Despite this he is arguably England’s greatest composer some of whose orchestral music has traveled around the world more than any of his compatriots. In addition to the Conceros, his 3 Symphonies and Enigma Variations are his other orchestral masterpieces. His many other works for orchestra, including the Pomp and Circumstance Marches, Falstaff and Cockaigne Overture have been recorded numerous times. He was appointed Master of the King’s Musick in 1924. Piano Concerto (arranged by Robert Walker from sketches, drafts and recordings) (1913/2004) David Owen Norris (piano)/David Lloyd-Jones/BBC Concert Orchestra ( + Four Songs {orch. Haydn Wood}, Adieu, So Many True Princesses, Spanish Serenade, The Immortal Legions and Collins: Elegy in Memory of Edward Elgar) DUTTON EPOCH CDLX 7148 (2005) Violin Concerto in B minor, Op. 61 (1909-10) Salvatore Accardo (violin)/Richard Hickox/London Symphony Orchestra ( + Walton: Violin Concerto) BRILLIANT CLASSICS 9173 (2010) (original CD release: COLLINS CLASSICS COL 1338-2) (1992) Hugh Bean (violin)/Sir Charles Groves/Royal Liverpool Philharmonic Orchestra ( + Violin Sonata, Piano Quintet, String Quartet, Concert Allegro and Serenade) CLASSICS FOR PLEASURE CDCFP 585908-2 (2 CDs) (2004) (original LP release: HMV ASD2883) (1973) -

BMN 2001/3.Indd

Bohuslav Martinů September – December 2001 40 Years with the Name Martinů Martinů in a Different Light Martinů Events Martinů and his Homes in Nice Today News Boston’s Martinů on Tour Where Martinů is at Home Third issue The International Bohuslav Martinů Society The Bohuslav Martinů Institute CONTENTS WELCOME Karel Van Eycken ................................................. 3 40 YEARS WITH THE NAME MARTINŮ The Bohuslav Martinů Piano Quartet will Celebrate a Major Anniversary Next Season Emil Leichner ......................................................4 A BLUE DOMAIN Stuart Wilson ......................................................5 MARTINŮ EVENTS 2001 ........................6 - 8 BOSTON’S MARTINŮ ON TOUR Gregory Terian .................................................... 7 MEMBERS’ DIARY ................................................ 8 ANNOUNCEMENT Gramophone Award for Magdalena Kožená ............... 8 MARTINŮ IN A DIFFERENT LIGHT The Musical Film for Television as a Form of Interpreting Chamber Stage Works by Bohuslav Martinů Jiří Nekvasil ....................................................... 9 MARTINŮ AND HIS HOMES IN NICE TODAY Karel Van Eycken and Marcel J. Schneider ................12 FROM GREG TERIAN’S MARTINŮ REVIEW in The Dvořák Society Newsletter ...........................13 NEWS ............................................... 14 - 15 DUOS AND TRIO FOR STRINGS Review Sandra Bergmannová ..........................................15 BOHUSLAV MARTINŮ’S CORRESPONDENCE IN THE MUSEUM OF NATIONAL LITERATURE IN PRAGUE Kateřina -

Vol.21 No 2 August 2018

Journal August 2018 Vol. 21, No. 2 The Elgar Society Journal 18 Holtsmere Close, Watford, Herts., WD25 9NG Email: [email protected] August 2018 Vol. 21, No. 2 Cross against Corselet: Elgar, Longfellow, and the Saga of King Olaf 3 President John T. Hamilton Julian Lloyd Webber FRCM Elgar’s King Olaf – an illustrated history 15 John Norris, Arthur Reynolds Vice-Presidents To the edge of the Great Unknown: 1,000 Miles up the Amazon 27 Diana McVeagh Martin Bird Dame Janet Baker, CH, DBE Leonard Slatkin Book reviews 41 Sir Andrew Davis, CBE Barry Collett Donald Hunt, OBE Christopher Robinson, CVO, CBE CD reviews 43 Andrew Neill Barry Collett, Andrew Neill, Michael Schwalb Sir Mark Elder, CBE Martyn Brabbins DVD reviews 54 Tasmin Little, OBE Ian Lace Letters 56 Jerrold Northrop Moore, Andrew Neill, Arthur Reynolds Chairman Steven Halls Elgar viewed from afar 58 Alan Tongue, Martin Bird Vice-Chairman Stuart Freed 100 Years Ago 69 Martin Bird Treasurer Helen Whittaker Secretary George Smart The Editor does not necessarily agree with the views expressed by contributors, nor does the Elgar Society accept responsibility for such views. Front Cover: Front Cover: Edward William Elgar (1857-1934; Arthur Reynolds’ Archive) and Henry Wadsworth Longfellow (1807-1882; Charles Kaufmann’s Archive). Notes for Contributors. Please adhere to these as far as possible if you deliver writing (as is much preferred) in Microsoft Word or Rich Text Format. Copyright: it is the contributor’s responsibility to be reasonably sure that copyright permissions, if Cross against Corselet required, are obtained. Elgar, Longfellow, and the Saga of King Olaf Illustrations (pictures, short music examples) are welcome, but please ensure they are pertinent, cued into the text, and have captions. -

The Death of Christian Culture

Memoriœ piœ patris carrissimi quoque et matris dulcissimœ hunc libellum filius indignus dedicat in cordibus Jesu et Mariœ. The Death of Christian Culture. Copyright © 2008 IHS Press. First published in 1978 by Arlington House in New Rochelle, New York. Preface, footnotes, typesetting, layout, and cover design copyright 2008 IHS Press. Content of the work is copyright Senior Family Ink. All rights reserved. Portions of chapter 2 originally appeared in University of Wyoming Publications 25(3), 1961; chapter 6 in Gary Tate, ed., Reflections on High School English (Tulsa, Okla.: University of Tulsa Press, 1966); and chapter 7 in the Journal of the Kansas Bar Association 39, Winter 1970. No portion of this work may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote brief passages in a review, or except in cases where rights to content reproduced herein is retained by its original author or other rights holder, and further reproduction is subject to permission otherwise granted thereby according to applicable agreements and laws. ISBN-13 (eBook): 978-1-932528-51-0 ISBN-10 (eBook): 1-932528-51-2 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Senior, John, 1923– The death of Christian culture / John Senior; foreword by Andrew Senior; introduction by David Allen White. p. cm. Originally published: New Rochelle, N.Y. : Arlington House, c1978. ISBN-13: 978-1-932528-51-0 1. Civilization, Christian. 2. Christianity–20th century. I. Title. BR115.C5S46 2008 261.5–dc22 2007039625 IHS Press is the only publisher dedicated exclusively to the social teachings of the Catholic Church. -

CHAN 6652 BOOK.Qxd 22/5/07 4:33 Pm Page 2

CHAN 6652 Cover.qxd 22/5/07 4:31 pm Page 1 CHAN 6652 CHAN 6652 BOOK.qxd 22/5/07 4:33 pm Page 2 Sir Edward Elgar (1857–1934) Elgar: Overtures 1 Froissart, Op. 19 13:48 Concert Overture In his essay on Elgar’s In the South, Donald end of his life, Elgar retained an affection for Tovey, Reid Professor at Edinburgh University Froissart, his first orchestral work of real 2 Cockaigne (In London Town), Op. 40 14:18 and as canny a practical musician as he was a significance. ‘It is difficult to believe that I Concert Overture theorist, writes of conducting the overture wrote it in 1890!’ he exclaimed with typical with a student orchestra: ingenuousness to Fred Gaisberg of His 3 In the South (Alassio), Op. 50 20:32 I shall not easily forget my impression when, on Master’s Voice after recording the overture in Concert Overture first attacking [it] with considerable fear and February 1933, ‘it sounds so brilliant and expectation of its being as difficult as it is fresh.’ Incentive to write it had come in the George Frideric Handel (1685–1759) – brilliant, I found that it simply carried the form of a commission from the Worcester orchestra away with it, and seemed to play itself Festival – a faintly ironic stroke of luck, since Sir Edward Elgar at the first rehearsal. On inquiry, I found that one Elgar, born in Broadheath, had recently settled single member of the orchestra was not reading it in London. Things had at last started to look 4 Overture in D minor (1923) 5:13 at sight… I and my students had never had a up for this son of a local piano tuner. -

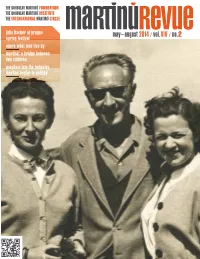

May–August 2014/ Vol.XIV / No.2

THE BOHUSLAV MARTINŮ FOUNDATION THE BOHUSLAV MARTINŮ INSTITUTE THE INTERNATIONAL MARTINŮ CIRCLE MR julia fischer at prague may–august 2014 / vol.XIV / no.2 spring festival opera what men live by martinů: a bridge between two cultures peephole into the bohuslav martinů center in polička BOHUSLAVMARTINŮ INTHEYEAR OFCZECH MUSIC & BOHUSLAVMARTINŮ DAYS contents 2014 3 PROLOGUE 4 14+15+16 SEPTEMBER 2014 9.00 pm . Lesser Town of Prague Cemetery 5 Eva Blažíčková – choreographer MARTINŮ . The Bouquet of Flowers, H 260 6 7 OCTOBER 2014 . 8.30 pm . HAMU, Martinů Hall, Prague BOHUSLAV MARTINŮ’S SOLDIER Concert in the occasion of 100th anniversary of Josef Páleníček’s birth Smetana Trio, Wenzel Grund – clarinet AND DANCER MARTINŮ . Piano Trio No 2, H 327 OLGA JANÁČKOVÁ (+ PÁLENÍČEK, JANÁČEK) THE SOLDIER AND THE DANCER IN PLZEŇ 2 NOVEMBER 2014 . 7.00 pm . National Theatre, Prague EVA VELICKÁ Ballet ensemble of the National Moravian-Silesian Theatre, Nataša Novotná – choreographer 8 MARTINŮ . The Strangler, H 314 (+ SMETANA, JANÁČEK) GEOFF PIPER MARTINA FIALKOVÁ 2 DECEMBER 2014 . 5.00 pm . Hall of Prague Conservatory Concert Marking the 40th Anniversary of the Dvořák Society for Czech and Slovak Music – programme see page 3 10 JULIA FISCHER AT PRAGUE SPRING BOHUSLAV . MARTINU DAYS FESTIVAL FRANK KUZNIK 30 NOVEMBER 2014 . 7.00 pm . HAMU, Martinů Hall, Prague TWO STARS ENCHANT THE RUDOLFINUM Concert of the winners of Bohuslav Martinů Competition PRAVOSLAV KOHOUT in the Category Piano Trio and String Quartet 2 DECEMBER 2014 . 7.30 pm . HAMU, Martinů Hall, Prague 12 Kühn Children's Choir, choirmasters: Jiří Chvála, Petr Louženský WHAT MEN LIVE BY Panocha Quartet members (Jiří Panocha, Pavel Zejfart – violin, GREGORY TERIAN Miroslav Sehnoutka – viola), Jan Kalfus – organ, Petr Kostka – recitation, Ivan Kusnjer – baritone, Daniel Wiesner – piano MARTINŮ . -

BOHUSLAV MARTINŮ JAROSLAV MIHULE / 2008 František Martinů, Colored Drawing from a Scrapbook

A POCKET GUIDE TO THE LIFE AND WORK OF BOHUSLAV MARTINŮ JAROSLAV MIHULE / 2008 František Martinů, colored drawing from a scrapbook 1 FROM POLIČKA TO PRAGUE 1890 — 1922 2 On The Polička Tower 1.1 Bohuslav came into the world in a tiny room on the gallery of the church tower where his father, Ferdinand Martinů, apart from being a shoemaker, also carried out a unique job as the tower- keeper, bell-ringer and watchman. Polička - St. James´ Church and the Bastion “On December 8th, the crow brought us a male, a boy, and on Dec. 14th 1.2 A Loving Family he was baptized as It was the mother who energetically took charge of the whole family. She was Bohuslav Jan.” the paragon of order and discipline: strict, pious – a Roman Catholic, naturally, as (The composer’s father were most inhabitants of this hilly region. made this entry in the Of course, she loved all of her children. With Ferdinand Martinů she had fi ve; and family chronicle.) the youngest and probably the most coddled was Bohuslav, born to the accom- paniment of the festive ringing of all the bells, as the town celebrated on that day the holiday of the Immaculate Conception of the Virgin Mary. To be born high above the ground, almost within the reach of the sky, seemed in itself to promise an exceptional life ahead. Also his brother František and his sister Marie had their own special talents. František graduated from art school and made use of his artistic skills above all 3 as a restorer and conservator of church art objects in his homeland as well as abroad. -

Newsletter 2-2005

THE BOHUSLAV MARTINŮ FOUNDATION & THE BOHUSLAV MARTINŮ INSTITUTE MAY—AUGUST 2005 The Greek Passion / VOL. Finally in Greece V / NO. Interview with Neeme Järvi 2 Martinů & Hans Kindler The Final Years ofthe Life of Bohuslav Martinů Antonín Tučapský on Martinů NEWS & EVENTS ts– Conten VOL. V / NO.2 MAY—AUGUST 2005 Bohuslav Martinů in Liestal, May 1956 > Photo from Max Kellerhals’archive e WelcomE —EDITORIAL —REPORT OF MAY SYMPOSIUM OF EDITORIAL BOARD —INTERNATIONAL MARTINŮ CIRCLE r Reviews —BBC SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA —CD REVIEWS —GILGAMESH y Reviews f Research THE GREEK PASSION THE FINAL YEARS OF THE FINALLY IN GREECE LIFE OF BOHUSLAV MARTINŮ • ALEŠ BŘEZINA • LUCIE BERNÁ u Interview j Memoirs WITH… NEEME JÄRVI ANTONÍN TUČAPSKÝ • EVA VELICKÁ ON MARTINŮ i Research k Events MARTINŮ & HANS KINDLER —CONCERTS • F. JAMES RYBKA & BORIS I. RYBKA —BALLETS —FESTIVALS a Memoirs l News MEMORIES OF —THE MARTINŮ INSTITUTE’S CORNER MONSIEUR MARTINŮ —NEW RECORDING —OBITUARIES • ADRIAN SCHÜRCH —BOHUSLAV MARTINŮ DISCUSSION GROUP me– b Welco THE BOHUSLAV MARTINŮ REPORT ON THE MAY SYMPOSIUM OF THE EDITORIAL NEWSLETTER is published by the Bohuslav Martinů EDITORIAL BOARD Foundation in collaboration with the DEAR READERS, Bohuslav Martinů Institute in Prague THE MEETING of the editorial board in 2005 was held on 14–15 May in the premises we are happy to present the new face of the Bohuslav Martinů Institute. It was attended by the chair of the editorial board of the Bohuslav Martinů Newsletter, EDITORS Aleš Březina as well as Sandra Bergmannová of the Charles University Institute of published by the Bohuslav Martinů Zoja Seyčková Musicology and the Bohuslav Martinů Institute, Dietrich Berke, Klaus Döge of the Foundation and Institute.We hope you Jindra Jilečková Richard Wagner-Gesamtausgabe, Jarmila Gabrielová of the Charles University Institute will enjoy the new graphical look. -

Musicologica Olomucensia 18

ACTA UNIVERSITATIS PALACKIANAE OLOMUCENSIS FACULTAS PHILOSOPHICA PHILOSOPHICA – AESTHETICA 42 – 2013 MUSICOLOGICA OLOMUCENSIA 18 Universitas Palackiana Olomucensis 2013 Musicologica Olomucensia Editor-in-chief: Lenka Křupková Editorial Board: Michael Beckerman – New York University, NY; Mikuláš Bek – Masaryk University, Brno; Roman Dykast – Academy of Performing Arts, Prague; Jarmila Gabrielová – Charles University, Prague; Lubomír Chalupka – Komenský University, Bratislava; Dieter Torke- witz – Universität für Musik und darstellende Kunst, Wien; Jan Vičar – Palacký University, Olomouc Executive editor of Volume 18 (December 2013): Markéta Koutná This volume was published in 2013 under the project of the Ministry of Education – “Excellence in Education: Improvements in publishing opportunities for academic staff in arts and humanities at the Philosophical Faculty, Palacký University, Olomouc”. The scholarly journal Musicologica Olomucensia has been published twice a year (in June and December) since 2010 and follows up on the Palacký University proceedings Acta Universitatis Palackianae Olomucensis – Musicologica Olomucensia (founded in 1993) and Kritické edice hudebních památek [Critical Editions of Musical Documents] (founded in 1996). Journal Musicologica Olomucensia can be found on EBSCOhost databases. The present volume was submitted to print on October 30, 2013. Dieser Band wurde am 30. Oktober 2013 in Druck gegeben. Předáno do tisku 30. října 2013. [email protected] www.musicologicaolomucensia.upol.cz ISSN 1212-1193 -

The Muse of Fire: Liberty and War Songs As a Source of American History

3 7^ A'£?/</ THE MUSE OF FIRE: LIBERTY AND WAR SONGS AS A SOURCE OF AMERICAN HISTORY DISSERTATION Presented to the Graduate Council of the North Texas State University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY By Kent Adam Bowman, B.A., M.A Denton, Texas August, 1984 Bowman, Kent Adam, The Muse of Fire; Liberty and War Songs as a Source of American History. Doctor of Philosophy (History), August, 1984, 337 pp., bibliography, 135 titles. The development of American liberty and war songs from a few themes during the pre-Revolutionary period to a distinct form of American popular music in the Civil War period reflects the growth of many aspects of American culture and thought. This study therefore treats as historical documents the songs published in newspapers, broadsides, and songbooks during the period from 1765 to 1865. Chapter One briefly summarizes the development of American popular music before 1765 and provides other introductory material. Chapter Two examines the origin and development of the first liberty-song themes in the period from 1765 to 1775. Chapters Three and Four cover songs written during the American Revolution. Chapter Three describes battle songs, emphasizing the use of humor, and Chapter Four examines the figures treated in the war song. Chapter Five covers the War of 1812, concentrating on the naval song, and describes the first use of dialect in the American war song. Chapter Six covers the Mexican War (1846-1848) and includes discussion of the aggressive American attitude toward the war as evidenced in song.