Celtic Elements in Yeats's Early Poetry and Their Influence on Irish

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

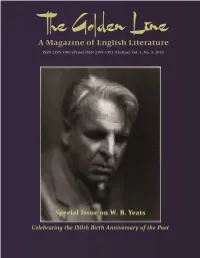

Online Version Available at Special Issue on WB Yeats Volume 1, Number 3, 2015

The Golden Line A Magazine of English Literature Online version available at www.goldenline.bcdedu.net Special Issue on W. B. Yeats Volume 1, Number 3, 2015 Guest-edited by Dr. Zinia Mitra Nakshalbari College, Darjeeling Published by The Department of English Bhatter College, Dantan P.O. Dantan, Dist. Paschim Medinipur West Bengal, India. PIN 721426 Phone: 03229-253238, Fax: 03229-253905 Website: www.bhattercollege.ac.in Email: [email protected] The Golden Line: A Magazine on English Literature Online version available at www.goldenline.bcdedu.net ISSN 2395-1583 (Print) ISSN 2395-1591 (Online) Inaugural Issue Volume 1, Number 1, 2015 Published by The Department of English Bhatter College, Dantan P.O. Dantan, Dist. Paschim Medinipur West Bengal, India. PIN 721426 Phone: 03229-253238, Fax: 03229-253905 Website: www.bhattercollege.ac.in Email: [email protected] © Bhatter College, Dantan Patron Sri Bikram Chandra Pradhan Hon’ble President of the Governing Body, Bhatter College Chief Advisor Pabitra Kumar Mishra Principal, Bhatter College Advisory Board Amitabh Vikram Dwivedi Assistant Professor, Shri Mata Vaishno Devi University, Jammu & Kashmir, India. Indranil Acharya Associate Professor, Vidyasagar University, West Bengal, India. Krishna KBS Assistant Professor in English, Central University of Himachal Pradesh, Dharamshala. Subhajit Sen Gupta Associate Professor, Department of English, Burdwan University. Editor Tarun Tapas Mukherjee Assistant Professor, Department of English, Bhatter College. Editorial Board Santideb Das Guest Lecturer, Department of English, Bhatter College Payel Chakraborty Guest Lecturer, Department of English, Bhatter College Mir Mahammad Ali Guest Lecturer, Department of English, Bhatter College Thakurdas Jana Guest Lecturer, Bhatter College ITI, Bhatter College External Board of Editors Asis De Assistant Professor, Mahishadal Raj College, Vidyasagar University. -

Shadows Deep: Change and Continuity in Yeats

Colby Quarterly Volume 22 Issue 4 December Article 3 December 1986 Shadows Deep: Change and Continuity in Yeats Donald Pearce Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.colby.edu/cq Recommended Citation Colby Library Quarterly, Volume 22, no.4, December 1986, p.198-204 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ Colby. It has been accepted for inclusion in Colby Quarterly by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ Colby. Pearce: Shadows Deep: Change and Continuity in Yeats Shadows Deep: Change and Continuity in Yeats by DONALD PEARCE He made songs because he had a will to make songs and not because love moved him thereto. Ue de Saint-eire VERY POET is, at bottom, a kind of alchemist, every poem an ap E paratus for transn1uting the "base metal" of life into the gold of art. Especially is this true of Yeats, not only as regards the ambient world of other people and events, but also the private one of his own art and thought: "Myself must I remake / Till I am Timon and Lear / Or that William Blake...." So persistent was he in this work of transmutation, and so adept at it, that the ordinary affairs of daily life often must have seemed to him little more than a clumsy version of a truer, more intense life lived in the clarified world of his imagination. However that may have been for Yeats, it is certainly true for his readers: incidents, persons, squabbles with which or whom he was intermittently entangled increas ingly owe what importance they still have for us to the fact of occurring somewhere, caught and finalized, in the passionate world of his poems. -

Urban Planning, Irish Modernism, and Dublin

Notes 1 Urbanizing the Revival: Urban Planning, Irish Modernism, and Dublin 1. Arguably Andrew Thacker betrays a similar underlying assumption when he writes of ‘After the Race’: ‘Despite the characterisation of Doyle as a rather shallow enthusiast for motoring, the excitement of the car’s “rapid motion through space” is clearly associated by Joyce with a European modernity to which he, as a writer, aspired’ (Thacker 115). 2. Wirth-Nesher’s understanding of the city, here, is influenced by that of Georg Simmel, whereby the city, while divesting individuals of a sense of communal belonging, also affords them a degree of personal freedom that is impossible in a smaller community (Wirth-Nesher 163). Due to the lack of anonymity in Joyce’s Dublin, an indicator of its pre-urban or non-urban status, this personal freedom is unavailable to Joyce’s characters. ‘There are almost no strangers’ in Dubliners, she writes, with the exceptions of those in ‘An Encounter’ and ‘Araby’ (164). She then enumerates no less than seven strangers in the collection, arguing however that they are ‘invented through the transformation of the familiar into the strange’ (164). 3. Wirth-Nesher’s assumptions about Dublin’s status as a city are not really necessary to the focus of her analysis, which emphasizes the importance Joyce’s early work places on the ‘indeterminacy of the public and private’ and its effects on the social lives of the characters (166). That she chooses to frame this analysis in terms of Dublin’s ‘exacting the price of city life and in turn offering the constraints of a small town’ (173) reveals forcefully the pervasiveness of this type of reading of Joyce’s Dublin. -

Hugh Macdiarmid and Sorley Maclean: Modern Makars, Men of Letters

Hugh MacDiarmid and Sorley MacLean: Modern Makars, Men of Letters by Susan Ruth Wilson B.A., University of Toronto, 1986 M.A., University of Victoria, 1994 A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in the Department of English © Susan Ruth Wilson, 2007 University of Victoria All rights reserved. This dissertation may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photo-copying or other means, without the permission of the author. ii Supervisory Committee Dr. Iain Higgins_(English)__________________________________________ _ Supervisor Dr. Tom Cleary_(English)____________________________________________ Departmental Member Dr. Eric Miller__(English)__________________________________________ __ Departmental Member Dr. Paul Wood_ (History)________________________________________ ____ Outside Member Dr. Ann Dooley_ (Celtic Studies) __________________________________ External Examiner ABSTRACT This dissertation, Hugh MacDiarmid and Sorley MacLean: Modern Makars, Men of Letters, transcribes and annotates 76 letters (65 hitherto unpublished), between MacDiarmid and MacLean. Four additional letters written by MacDiarmid’s second wife, Valda Grieve, to Sorley MacLean have also been included as they shed further light on the relationship which evolved between the two poets over the course of almost fifty years of friendship. These letters from Valda were archived with the unpublished correspondence from MacDiarmid which the Gaelic poet preserved. The critical introduction to the letters examines the significance of these poets’ literary collaboration in relation to the Scottish Renaissance and the Gaelic Literary Revival in Scotland, both movements following Ezra Pound’s Modernist maxim, “Make it new.” The first chapter, “Forging a Friendship”, situates the development of the men’s relationship in iii terms of each writer’s literary career, MacDiarmid already having achieved fame through his early lyrics and with the 1926 publication of A Drunk Man Looks at the Thistle when they first met. -

Fairy and Folk Tales of the Irish Peasantry, by 1

Fairy and Folk Tales of the Irish Peasantry, by 1 Fairy and Folk Tales of the Irish Peasantry, by William Butler Yeats This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: Fairy and Folk Tales of the Irish Peasantry Author: William Butler Yeats Editor: William Butler Yeats Release Date: October 28, 2010 [EBook #33887] Language: English Fairy and Folk Tales of the Irish Peasantry, by 2 Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK FAIRY AND FOLK TALES *** Produced by Larry B. Harrison, Brian Foley and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive/American Libraries.) FAIRY AND FOLK TALES OF THE IRISH PEASANTRY. EDITED AND SELECTED BY W. B. YEATS. THE WALTER SCOTT PUBLISHING CO., LTD. LONDON AND FELLING-ON-TYNE. NEW YORK: 3 EAST 14TH STREET. INSCRIBED TO MY MYSTICAL FRIEND, G. R. CONTENTS. THE TROOPING FAIRIES-- PAGE The Fairies 3 Frank Martin and the Fairies 5 The Priest's Supper 9 The Fairy Well of Lagnanay 13 Teig O'Kane and the Corpse 16 Paddy Corcoran's Wife 31 Cusheen Loo 33 The White Trout; A Legend of Cong 35 The Fairy Thorn 38 The Legend of Knockgrafton 40 A Donegal Fairy 46 CHANGELINGS-- The Brewery of Egg-shells 48 The Fairy Nurse 51 Jamie Freel and the Young Lady 52 The Stolen Child 59 THE MERROW-- -

Untitled.Pdf

STRUCTURE IN THE COLLECTED POEMS OF W. B. YEATS A Thesis Presented to the School of Graduate Studies Drake University In Partial Fulfil£ment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in English by Barbara L. Croft August 1970 l- ----'- _ u /970 (~ ~ 7cS"' STRUCTURE IN THE COLLECTED POEMS OF w. B. YEATS by Barbara L. Croft Approved by CGJmmittee: J4 .2fn., k ~~1""-'--- 7~~~ tI It t ,'" '-! -~ " -i L <_ j t , }\\ ) '~'l.p---------"'----------"? - TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter Page 1. INTRODUCTION ••••• . 1 2. COMPLETE OBJECTIVITY . • • . 23 3. THE DISCOVERY OF STRENGTH •••••••• 41 4. C~1PLETE SUBJECTIVITY •• • • • ••• 55 5. THE BREAKING OF STRENGTH ••••••••• 79 BIBLIOGRAPHY • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • 90 i1 CHAPTER I INTRODUCTION There is, needless to say, an abundance of criticism on W. B. Yeats. Obsessed with the peet's occultism, critics have pursued it to a depth which Yeats, a notedly poor scholar, could never have equalled; nor could he have matched their zeal for his politics. While it is not the purpose here to evaluate or even extensively to examine this criticism, two critics in particular, Richard Ellmann and John Unterecker, will preve especially valuable in this discussion. Ellmann's Yeats: ----The Man and The Masks is essentially a critical biography, Unterecker's ! Reader's Guide l! William Butler Yeats, while it uses biographical material, attempts to fecus upon critical interpretations of particular poems and groups of poems from the Collected Poems. In combination, the work of Ellmann and Unterecker synthesize the poet and his poetry and support the thesis here that the pattern which Yeats saw emerging in his life and which he incorporated in his work is, structurally, the same pattern of a death and rebirth cycle which he explicated in his philosophical book, A Vision. -

W. B. Yeat's Presence in James Joyce's a Portrait of The

udc 821.111-31.09 Joyce J. doi 10.18485/bells.2015.7.1 Michael McAteer Pázmány Péter Catholic University, Budapest, Hungary W. B. YEAT’S PRESENCE IN JAMES JOYCE’S A PORTRAIT OF THE ARTIST AS A YOUNG MAN Abstract In the context of scholarly re-evaluations of James Joyce’s relation to the literary revival in Ireland at the start of the twentieth century, this essay examines the significance of W.B. Yeats to A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man. It traces some of the debates around Celtic and Irish identity within the literary revival as a context for understanding the pre-occupations evident in Joyce’s novel, noting the significance of Yeats’s mysticism to the protagonist of Stephen Hero, and its persistence in A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man later. The essay considers the theme of flight in relation to the poetry volume that is addressed directly in the novel, Yeats’s 1899 collection, The Wind Among the Reeds. In the process, the influence of Yeats’s thought and style is observed both in Stephen Dedalus’s forms of expression and in the means through which Joyce conveys them. Particular attention is drawn to the notion of enchantment in the novel, and its relation to the literature of the Irish Revival. The later part of the essay turns to the 1899 performance of Yeats’s play, The Countess Cathleen, at the Antient Concert Rooms in Dublin, and Joyce’s memory of the performance as represented through Stephen towards the end of the novel. -

The Ironic Dialectic in Yeats

Colby Quarterly Volume 19 Issue 4 December Article 7 December 1983 The Ironic Dialectic in Yeats Lance Olsen Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.colby.edu/cq Recommended Citation Colby Library Quarterly, Volume 19, no.4, December 1983, p.215-220 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ Colby. It has been accepted for inclusion in Colby Quarterly by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ Colby. Olsen: The Ironic Dialectic in Yeats The Ironic Dialectic in Yeats by LANCE OLSEN UCH has been said about Yeats's mind working in terms of some M thing akin to the Hegelian dialectical triad in which a thesis and antithesis find resolution in a synthesis. Hegel, in whom Yeats was read ing widely by the middle of the 1920's, and toward whom the poet main tained a strong ambivalence throughout his life, would have it that it is in this dialectical triad "and in the comprehension of the unity of oppo sites, or of the positive in the negative, that speculative knowledge con sists."l But for Yeats the various sets of opposites he found in the world remained unresolved no matter how hard he fought toward resolution. In the running battle he had with them, he always failed to synthesize the diverse virtues in his many-sided debate with himself. The theses and antitheses with which he struggled never attained triadic unity. Instead, they survived as a series of clashing binaries: art/nature; youth/age; body/soul; passion/wisdom; beast/man; a Nietzschean Apollonian/ Dionysian; revelation /civilization; poetry/responsibility; time /eternity; being/becoming; the heroic/the non-heroic; and, finally, the ultimate dialectic between antitheses themselves and a Platonically ideal realm where antitheses in the end are annihilated. -

Literary Review

A BIRD’S EYE VIEW: EXPLORING THE BIRD IMAGERY IN THE LYRIC POETRY OF WILLIAM BUTLER YEATS By ERIN ELIZABETH RISNER A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate Studies Division of Ohio Dominican University Columbus, Ohio in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of MASTERS OF ARTS IN LIBERAL STUDIES MAY 2013 2 CERTIFICATION OF APPROVAL A BIRD’S EYE VIEW: EXPLORING THE BIRD IMAGERY IN THE LYRIC POETRY OF WILLIAM BUTLER YEATS By ERIN ELIZABETH RISNER Thesis Approved: _______________________________ ______________ Dr. Ronald W. Carstens, Ph.D. Date Professor of Political Science Chair, Liberal Studies Program ________________________________ ______________ Dr. Martin R. Brick, Ph.D. Date Assistant Professor of English _________________________________ ______________ Dr. Ann C. Hall, Ph. D. Date Professor of English 3 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I wish to express my appreciation to Dr. Martin Brick for all of his help and patience during this long, but rewarding, process. I also wish to thank Dr. Ann Hall for her final suggestions on this thesis and her Irish literature class two years ago that began this journey. A special thank you to Dr. Ron Carstens for his final review of this thesis and guidance through Ohio Dominican University’s MALS program. I must also give thanks to Dr. Beth Sutton-Ramspeck, who has guided me through academia since English Honors my freshman year at OSU-Lima. Final acknowledgements go to my family and friends. To my husband, Axle, thank you for all of your love and support the past three years. To my parents, Bob and Liz, I am the person I am today because of you. -

Predetermination and Nihilism in W. B. Yeats's Theatre

Revista Alicantina de Estudios Ingleses 5 (1992): 143-53 Predetermination and Nihilism in W. B. Yeats's Theatre Francisco Javier Torres Ribelles University of Alicante ABSTRACT This paper puts forward the hypothesis that Yeats's theatre is affected by a determinist component that governs it. This dependence is held to be the natural consequence of his desire to créate a universal art, a wish that confines the writer to a limited number of themes, death and oíd age being the most important. The paper also argües that the deter- minism is positive in the early stage but that it clearly evolves towards a negative kind. In spite of the playwright's acknowledged interest in doctrines related to the occult, the necessity of a more critical analysis is also put forward. The paper goes on to suggest that underlying the negative determinism of Yeats's late period there is a nihilistic view of life, of life after death and even of the work of art. The paper concludes by arguing that the poet may have exaggerated his pose as a response to his admitted inability to change the modern world and as a means of overcoming his sense of impending annihilation. The attitude underlying Yeats's earliest plays is radically opposed to what we find in the final ones. In the first stage, the determinism to which the subject matter inevitably leads is given a positive character by being adapted to the author's perspective. There is an emphasis on the power of art and a celebration of the Nietzschean-romantic valúes defended by the poet. -

Diplomarbeit

DIPLOMARBEIT Titel der Diplomarbeit “Fairies, Witches, and the Devil: The Interface between Elite Demonology and Folk Belief in Early Modern Scottish Witchcraft Trials” Verfasserin Ruth Egger, BA angestrebter akademischer Grad Magistra (Mag.) Wien, 2014 Studienkennzahl lt. Studienblatt: A 057 327 Studienrichtung lt. Studienblatt: Individuelles Diplomstudium Keltologie Betreuerin: Dr Lizanne Henderson BA (Guelph) MA (Memorial) PhD (Strathclyde) 1 Acknowledgements First of all, I want to thank all my lecturers in history who introduced me to the basic theories and methods of historiography, but also to those providing lessons for Celtic Studies who made me aware of the importance of looking beyond the boundaries of one’s own discipline. Their interdisciplinary approach of including archaeology, linguistics, literature studies, cultural studies, and anthropology among other disciplines into historical research has inspired me ever since. Regarding this current study, I specially want to thank Dr. Lizanne Henderson who not only introduced me into the basic theories of methods of studying witchcraft and the supernatural during my time as Erasmus-student at the University of Glasgow, but also guided me during the writing process of this dissertation. Furthermore, I would like to thank the University of Vienna for giving me the chance to study abroad as Erasmus-student and also for providing me with a scholarship so that I could do the literature research for this dissertation at the University of Glasgow library and the National Archives of Scotland. Also, I thank Univ.-Prof. Mag. Dr. Melanie Malzahn for supporting me in acquiring this scholarship and helping me finding a viable topic for the dissertation, as well as Univ.-Doz. -

Xerox University Microfilms 900 North Zaab Road Ann Arbor, Michigan 49100 Ll I!

INFORMATION TO USERS This material was produced from a microfilm copy of the original document. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality Is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. 1.The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a large round black mark, it is an indication that the photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during exposure and thus cause a blurred image. You will find a good (mage of the page in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., was part of the material being photographed the photographer followed a definite method in "sectioning" the material. It is customary to begin photoing at the upper left hand corner of a large sheet and to continue photoing from left to right in equal sections with a small overlap. If necessary, sectioning is continued again — beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. 4. The majority of users indicate that the textual content is of greatest value, however, a somewhat higher quality reproduction could be made from "photographs" if essential to the understanding of the dissertation.