Predetermination and Nihilism in W. B. Yeats's Theatre

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Phil. 173: Metaethics Apr. 25, 2018 Lecture 27: Is Expressivism Nihilism? Is Relativism Nihilism? I

Phil. 173: Metaethics Apr. 25, 2018 Lecture 27: Is Expressivism Nihilism? Is Relativism Nihilism? I. Lewis’ Argument That Quasi-Realism Is Fictionalism (and Hence a Form of Nihilism) Suppose Blackburn’s quasi-realist project has succeeded perfectly on its own terms. Then the quasi-realist can, and will, echo everything the moral realist says. Rosen’s question: So what, then, makes the quasi-realist not simply a realist? Lewis’ reply: We shouldn’t look for something the realist says that the quasi-realist will not echo. Rather, we should look for something the quasi-realist says that the realist will not echo. In particular, even though at the end of the day the quasi-realist apes everything the realist says, at the beginning of the day the quasi-realist starts by expressing his commitment to projectivism. According to Lewis, this statement of projectivism acts as a disowning preface that turns the quasi-realist’s later realist-sounding assertions into fictive assertions of the sort uttered by a moral fictionalist. It’s as if the quasi- realist started out by saying, “Let’s make believe that moral realism is true, though it isn’t.” More formally, Lewis argues as follows (see p. 319): 1. One aim of quasi-realism is (to earn the right) to say what the moral realist says. [premise] 2. To say what the moral realist says is either to be a moral realist or to make-believedly be a moral realist. [premise] 3. So, an aim of quasi-realism is either to be a moral realist or to make-believedly be a moral realist. -

Between Dualism and Immanentism Sacramental Ontology and History

religions Article Between Dualism and Immanentism Sacramental Ontology and History Enrico Beltramini Department of Philosophy and Religious Studies, Notre Dame de Namur University, Belmont, CA 94002, USA; [email protected] Abstract: How to deal with religious ideas in religious history (and in history in general) has recently become a matter of discussion. In particular, a number of authors have framed their work around the concept of ‘sacramental ontology,’ that is, a unified vision of reality in which the secular and the religious come together, although maintaining their distinction. The authors’ choices have been criticized by their fellow colleagues as a form of apologetics and a return to integralism. The aim of this article is to provide a proper context in which to locate the phenomenon of sacramental ontology. I suggest considering (1) the generation of the concept of sacramental ontology as part of the internal dialectic of the Christian intellectual world, not as a reaction to the secular; and (2) the adoption of the concept as a protection against ontological nihilism, not as an attack on scientific knowledge. Keywords: sacramental ontology; history; dualism; immanentism; nihilism Citation: Beltramini, Enrico. 2021. Between Dualism and Immanentism Sacramental Ontology and History. Religions 12: 47. https://doi.org/ 1. Introduction 10.3390rel12010047 A specter is haunting the historical enterprise, the specter of ‘sacramental ontology.’ Received: 3 December 2020 The specter of sacramental ontology is carried by a generation of Roman Catholic and Accepted: 23 December 2020 Evangelical historians as well as historical theologians who aim to restore the sacred dimen- 1 Published: 11 January 2021 sion of nature. -

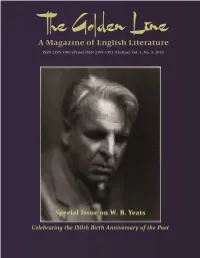

Online Version Available at Special Issue on WB Yeats Volume 1, Number 3, 2015

The Golden Line A Magazine of English Literature Online version available at www.goldenline.bcdedu.net Special Issue on W. B. Yeats Volume 1, Number 3, 2015 Guest-edited by Dr. Zinia Mitra Nakshalbari College, Darjeeling Published by The Department of English Bhatter College, Dantan P.O. Dantan, Dist. Paschim Medinipur West Bengal, India. PIN 721426 Phone: 03229-253238, Fax: 03229-253905 Website: www.bhattercollege.ac.in Email: [email protected] The Golden Line: A Magazine on English Literature Online version available at www.goldenline.bcdedu.net ISSN 2395-1583 (Print) ISSN 2395-1591 (Online) Inaugural Issue Volume 1, Number 1, 2015 Published by The Department of English Bhatter College, Dantan P.O. Dantan, Dist. Paschim Medinipur West Bengal, India. PIN 721426 Phone: 03229-253238, Fax: 03229-253905 Website: www.bhattercollege.ac.in Email: [email protected] © Bhatter College, Dantan Patron Sri Bikram Chandra Pradhan Hon’ble President of the Governing Body, Bhatter College Chief Advisor Pabitra Kumar Mishra Principal, Bhatter College Advisory Board Amitabh Vikram Dwivedi Assistant Professor, Shri Mata Vaishno Devi University, Jammu & Kashmir, India. Indranil Acharya Associate Professor, Vidyasagar University, West Bengal, India. Krishna KBS Assistant Professor in English, Central University of Himachal Pradesh, Dharamshala. Subhajit Sen Gupta Associate Professor, Department of English, Burdwan University. Editor Tarun Tapas Mukherjee Assistant Professor, Department of English, Bhatter College. Editorial Board Santideb Das Guest Lecturer, Department of English, Bhatter College Payel Chakraborty Guest Lecturer, Department of English, Bhatter College Mir Mahammad Ali Guest Lecturer, Department of English, Bhatter College Thakurdas Jana Guest Lecturer, Bhatter College ITI, Bhatter College External Board of Editors Asis De Assistant Professor, Mahishadal Raj College, Vidyasagar University. -

Echoes of the Orient: the Writings of William Quan Judge

ECHOES ORIENTof the VOLUME I The Writings of William Quan Judge Echoes are heard in every age of and their fellow creatures — man and a timeless path that leads to divine beast — out of the thoughtless jog trot wisdom and to knowledge of our pur- of selfish everyday life.” To this end pose in the universal design. Today’s and until he died, Judge wrote about resurgent awareness of our physical the Way spoken of by the sages of old, and spiritual inter dependence on this its signposts and pitfalls, and its rel- grand evolutionary journey affirms evance to the practical affairs of daily those pioneering keynotes set forth in life. HPB called his journal “pure Bud- the writings of H. P. Blavatsky. Her dhi” (awakened insight). task was to re-present the broad This first volume of Echoes of the panorama of the “anciently universal Orient comprises about 170 articles Wisdom-Religion,” to show its under- from The Path magazine, chronologi- lying expression in the world’s myths, cally arranged and supplemented by legends, and spiritual traditions, and his popular “Occult Tales.” A glance to show its scientific basis — with at the contents pages will show the the overarching goal of furthering the wide range of subjects covered. Also cause of universal brotherhood. included are a well-documented 50- Some people, however, have page biography, numerous illustra- found her books diffi cult and ask for tions, photographs, and facsimiles, as something simpler. In the writings of well as a bibliography and index. William Q. Judge, one of the Theosophical Society’s co-founders with HPB and a close personal colleague, many have found a certain William Quan Judge (1851-1896) was human element which, though not born in Dublin, Ireland, and emigrated lacking in HPB’s works, is here more with his family to America in 1864. -

W. B. Yeats Selected Poems

W. B. Yeats Selected Poems Compiled by Emma Laybourn 2018 This is a free ebook from www.englishliteratureebooks.com It may be shared or copied for any non-commercial purpose. It may not be sold. Cover picture shows Ben Bulben, County Sligo, Ireland. Contents To return to the Contents list at any time, click on the arrow ↑ before each poem. Introduction From The Wanderings of Oisin and other poems (1889) The Song of the Happy Shepherd The Indian upon God The Indian to his Love The Stolen Child Down by the Salley Gardens The Ballad of Moll Magee The Wanderings of Oisin (extracts) From The Rose (1893) To the Rose upon the Rood of Time Fergus and the Druid The Rose of the World The Rose of Battle A Faery Song The Lake Isle of Innisfree The Sorrow of Love When You are Old Who goes with Fergus? The Man who dreamed of Faeryland The Ballad of Father Gilligan The Two Trees From The Wind Among the Reeds (1899) The Lover tells of the Rose in his Heart The Host of the Air The Unappeasable Host The Song of Wandering Aengus The Lover mourns for the Loss of Love He mourns for the Change that has come upon Him and his Beloved, and longs for the End of the World He remembers Forgotten Beauty The Cap and Bells The Valley of the Black Pig The Secret Rose The Travail of Passion The Poet pleads with the Elemental Powers He wishes his Beloved were Dead He wishes for the Cloths of Heaven From In the Seven Woods (1904) In the Seven Woods The Folly of being Comforted Never Give All the Heart The Withering of the Boughs Adam’s Curse Red Hanrahan’s Song about Ireland -

Shadows Deep: Change and Continuity in Yeats

Colby Quarterly Volume 22 Issue 4 December Article 3 December 1986 Shadows Deep: Change and Continuity in Yeats Donald Pearce Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.colby.edu/cq Recommended Citation Colby Library Quarterly, Volume 22, no.4, December 1986, p.198-204 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ Colby. It has been accepted for inclusion in Colby Quarterly by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ Colby. Pearce: Shadows Deep: Change and Continuity in Yeats Shadows Deep: Change and Continuity in Yeats by DONALD PEARCE He made songs because he had a will to make songs and not because love moved him thereto. Ue de Saint-eire VERY POET is, at bottom, a kind of alchemist, every poem an ap E paratus for transn1uting the "base metal" of life into the gold of art. Especially is this true of Yeats, not only as regards the ambient world of other people and events, but also the private one of his own art and thought: "Myself must I remake / Till I am Timon and Lear / Or that William Blake...." So persistent was he in this work of transmutation, and so adept at it, that the ordinary affairs of daily life often must have seemed to him little more than a clumsy version of a truer, more intense life lived in the clarified world of his imagination. However that may have been for Yeats, it is certainly true for his readers: incidents, persons, squabbles with which or whom he was intermittently entangled increas ingly owe what importance they still have for us to the fact of occurring somewhere, caught and finalized, in the passionate world of his poems. -

YEATS ANNUAL No. 18 Frontispiece: Derry Jeffares Beside the Edmund Dulac Memorial Stone to W

To access digital resources including: blog posts videos online appendices and to purchase copies of this book in: hardback paperback ebook editions Go to: https://www.openbookpublishers.com/product/194 Open Book Publishers is a non-profit independent initiative. We rely on sales and donations to continue publishing high-quality academic works. In the same series YEATS ANNUALS Nos. 1, 2 Edited by Richard J. Finneran YEATS ANNUALS Nos. 3-8, 10-11, 13 Edited by Warwick Gould YEATS AND WOMEN: YEATS ANNUAL No. 9: A Special Number Edited by Deirdre Toomey THAT ACCUSING EYE: YEATS AND HIS IRISH READERS YEATS ANNUAL No. 12: A Special Number Edited by Warwick Gould and Edna Longley YEATS AND THE NINETIES YEATS ANNUAL No. 14: A Special Number Edited by Warwick Gould YEATS’S COLLABORATIONS YEATS ANNUAL No. 15: A Special Number Edited by Wayne K. Chapman and Warwick Gould POEMS AND CONTEXTS YEATS ANNUAL No. 16: A Special Number Edited by Warwick Gould INFLUENCE AND CONFLUENCE: YEATS ANNUAL No. 17: A Special Number Edited by Warwick Gould YEATS ANNUAL No. 18 Frontispiece: Derry Jeffares beside the Edmund Dulac memorial stone to W. B. Yeats. Roquebrune Cemetery, France, 1986. Private Collection. THE LIVING STREAM ESSAYS IN MEMORY OF A. NORMAN JEFFARES YEATS ANNUAL No. 18 A Special Issue Edited by Warwick Gould http://www.openbookpublishers.com © 2013 Gould, et al. (contributors retain copyright of their work). The text of this book is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported Licence. This licence allows you to share, copy, distribute and transmit the text; to adapt the text and to make commercial use of the text. -

Untitled.Pdf

STRUCTURE IN THE COLLECTED POEMS OF W. B. YEATS A Thesis Presented to the School of Graduate Studies Drake University In Partial Fulfil£ment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in English by Barbara L. Croft August 1970 l- ----'- _ u /970 (~ ~ 7cS"' STRUCTURE IN THE COLLECTED POEMS OF w. B. YEATS by Barbara L. Croft Approved by CGJmmittee: J4 .2fn., k ~~1""-'--- 7~~~ tI It t ,'" '-! -~ " -i L <_ j t , }\\ ) '~'l.p---------"'----------"? - TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter Page 1. INTRODUCTION ••••• . 1 2. COMPLETE OBJECTIVITY . • • . 23 3. THE DISCOVERY OF STRENGTH •••••••• 41 4. C~1PLETE SUBJECTIVITY •• • • • ••• 55 5. THE BREAKING OF STRENGTH ••••••••• 79 BIBLIOGRAPHY • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • 90 i1 CHAPTER I INTRODUCTION There is, needless to say, an abundance of criticism on W. B. Yeats. Obsessed with the peet's occultism, critics have pursued it to a depth which Yeats, a notedly poor scholar, could never have equalled; nor could he have matched their zeal for his politics. While it is not the purpose here to evaluate or even extensively to examine this criticism, two critics in particular, Richard Ellmann and John Unterecker, will preve especially valuable in this discussion. Ellmann's Yeats: ----The Man and The Masks is essentially a critical biography, Unterecker's ! Reader's Guide l! William Butler Yeats, while it uses biographical material, attempts to fecus upon critical interpretations of particular poems and groups of poems from the Collected Poems. In combination, the work of Ellmann and Unterecker synthesize the poet and his poetry and support the thesis here that the pattern which Yeats saw emerging in his life and which he incorporated in his work is, structurally, the same pattern of a death and rebirth cycle which he explicated in his philosophical book, A Vision. -

Hermetic Philosophy and Dual Selfhood in Yeats's

“An Image of Mysterious Wisdom”: Hermetic Philosophy and Dual Selfhood in Yeats’s Poetic Dialogues Treball de Fi de Grau/ BA dissertation Author: Paula Moschini Izquierdo Supervisor: Jordi Coral Escolà Departament de Filologia Anglesa i de Germanística Grau d’Estudis Anglesos June 2018 CONTENTS 0. Introduction ...................................................................................................................... 1 0.1. Methodology and Analysed Concepts ................................................................................... 1 0.2. Yeats and Philosophy: The Self and the Antinomies ......................................................... 2 0.3. The Hermetic Dialogue ............................................................................................................. 7 0.4. The Aesthetics of Artistic Reinterpretation: The Symbol ................................................ 9 1. Ego Dominus Tuus ....................................................................................................... 10 1.1. The Tower as a Symbol for the Self and “the Image” ..................................................... 11 1.2. Unity of Being in Artists ......................................................................................................... 14 1.3. A Poem about the Necessity of the Intuitive Wisdom in Poetry ................................... 16 2. A Dialogue of Self and Soul ........................................................................................ 18 2.1. Love and War: The Eternal -

An Argument for Moral Nihilism

Syracuse University SURFACE Syracuse University Honors Program Capstone Syracuse University Honors Program Capstone Projects Projects Spring 5-1-2010 An Argument for Moral Nihilism Tommy Fung Follow this and additional works at: https://surface.syr.edu/honors_capstone Part of the Other Philosophy Commons Recommended Citation Fung, Tommy, "An Argument for Moral Nihilism" (2010). Syracuse University Honors Program Capstone Projects. 335. https://surface.syr.edu/honors_capstone/335 This Honors Capstone Project is brought to you for free and open access by the Syracuse University Honors Program Capstone Projects at SURFACE. It has been accepted for inclusion in Syracuse University Honors Program Capstone Projects by an authorized administrator of SURFACE. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 1 An Argument for Moral Nihilism What if humans were just mere animals, and that we react to certain stimuli in a certain, lawful manner, and thus change in the appropriate way. It is debatable how much free will the average person would grant to say- a dog, but the average person doesn’t doubt that humans exercise free will. What if instead it could be shown that we are no different than a robot? That we are nothing but just an input-output mechanism for our programming to determine how to react to certain stimuli? I don’t know how many people who would claim that a robot exercises free will, or could be held morally responsible for their actions. “Science is more than the mere description of events as they occur. It is an attempt to discover order, to show that certain events stand in lawful relation to other events.. -

An Introduction to Philosophy

An Introduction to Philosophy W. Russ Payne Bellevue College Copyright (cc by nc 4.0) 2015 W. Russ Payne Permission is granted to copy, distribute and/or modify this document with attribution under the terms of Creative Commons: Attribution Noncommercial 4.0 International or any later version of this license. A copy of the license is found at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/ 1 Contents Introduction ………………………………………………. 3 Chapter 1: What Philosophy Is ………………………….. 5 Chapter 2: How to do Philosophy ………………….……. 11 Chapter 3: Ancient Philosophy ………………….………. 23 Chapter 4: Rationalism ………….………………….……. 38 Chapter 5: Empiricism …………………………………… 50 Chapter 6: Philosophy of Science ………………….…..… 58 Chapter 7: Philosophy of Mind …………………….……. 72 Chapter 8: Love and Happiness …………………….……. 79 Chapter 9: Meta Ethics …………………………………… 94 Chapter 10: Right Action ……………………...…………. 108 Chapter 11: Social Justice …………………………...…… 120 2 Introduction The goal of this text is to present philosophy to newcomers as a living discipline with historical roots. While a few early chapters are historically organized, my goal in the historical chapters is to trace a developmental progression of thought that introduces basic philosophical methods and frames issues that remain relevant today. Later chapters are topically organized. These include philosophy of science and philosophy of mind, areas where philosophy has shown dramatic recent progress. This text concludes with four chapters on ethics, broadly construed. I cover traditional theories of right action in the third of these. Students are first invited first to think about what is good for themselves and their relationships in a chapter of love and happiness. Next a few meta-ethical issues are considered; namely, whether they are moral truths and if so what makes them so. -

Nietzsche and Problem of Nihilism Zahra Meyboti University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee

University of Wisconsin Milwaukee UWM Digital Commons Theses and Dissertations August 2016 Nietzsche and Problem of Nihilism Zahra Meyboti University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.uwm.edu/etd Part of the Philosophy Commons Recommended Citation Meyboti, Zahra, "Nietzsche and Problem of Nihilism" (2016). Theses and Dissertations. 1389. https://dc.uwm.edu/etd/1389 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by UWM Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of UWM Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. NIETZSCHE AND PROBLEM OF NIHILISM by Zahra Meyboti A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in Philosophy at The University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee August 2016 ABSTRACT NIETZSCHE AND PROBLEM OF NIHILISM by Zahra Meyboti The University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, 2016 Under the Supervision of Professor William Bristow It is generally accepted that life-affirmation is central to Nietzsche’s philosophy. Nietzsche’s aim is to affirm life despite all miseries for human beings conscious of the horror and terror of existence and avoid nihilism. He is concerned with life affirmation almost in all of his works, In my thesis I will consider how he involved with avoiding nihilism to affirm life according to his two books The Birth of Tragedy and Genealogy of Morals. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Abstract .......................................................................................................................................ii