Yeats and Modernism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Online Version Available at Special Issue on WB Yeats Volume 1, Number 3, 2015

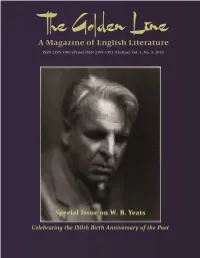

The Golden Line A Magazine of English Literature Online version available at www.goldenline.bcdedu.net Special Issue on W. B. Yeats Volume 1, Number 3, 2015 Guest-edited by Dr. Zinia Mitra Nakshalbari College, Darjeeling Published by The Department of English Bhatter College, Dantan P.O. Dantan, Dist. Paschim Medinipur West Bengal, India. PIN 721426 Phone: 03229-253238, Fax: 03229-253905 Website: www.bhattercollege.ac.in Email: [email protected] The Golden Line: A Magazine on English Literature Online version available at www.goldenline.bcdedu.net ISSN 2395-1583 (Print) ISSN 2395-1591 (Online) Inaugural Issue Volume 1, Number 1, 2015 Published by The Department of English Bhatter College, Dantan P.O. Dantan, Dist. Paschim Medinipur West Bengal, India. PIN 721426 Phone: 03229-253238, Fax: 03229-253905 Website: www.bhattercollege.ac.in Email: [email protected] © Bhatter College, Dantan Patron Sri Bikram Chandra Pradhan Hon’ble President of the Governing Body, Bhatter College Chief Advisor Pabitra Kumar Mishra Principal, Bhatter College Advisory Board Amitabh Vikram Dwivedi Assistant Professor, Shri Mata Vaishno Devi University, Jammu & Kashmir, India. Indranil Acharya Associate Professor, Vidyasagar University, West Bengal, India. Krishna KBS Assistant Professor in English, Central University of Himachal Pradesh, Dharamshala. Subhajit Sen Gupta Associate Professor, Department of English, Burdwan University. Editor Tarun Tapas Mukherjee Assistant Professor, Department of English, Bhatter College. Editorial Board Santideb Das Guest Lecturer, Department of English, Bhatter College Payel Chakraborty Guest Lecturer, Department of English, Bhatter College Mir Mahammad Ali Guest Lecturer, Department of English, Bhatter College Thakurdas Jana Guest Lecturer, Bhatter College ITI, Bhatter College External Board of Editors Asis De Assistant Professor, Mahishadal Raj College, Vidyasagar University. -

Shadows Deep: Change and Continuity in Yeats

Colby Quarterly Volume 22 Issue 4 December Article 3 December 1986 Shadows Deep: Change and Continuity in Yeats Donald Pearce Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.colby.edu/cq Recommended Citation Colby Library Quarterly, Volume 22, no.4, December 1986, p.198-204 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ Colby. It has been accepted for inclusion in Colby Quarterly by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ Colby. Pearce: Shadows Deep: Change and Continuity in Yeats Shadows Deep: Change and Continuity in Yeats by DONALD PEARCE He made songs because he had a will to make songs and not because love moved him thereto. Ue de Saint-eire VERY POET is, at bottom, a kind of alchemist, every poem an ap E paratus for transn1uting the "base metal" of life into the gold of art. Especially is this true of Yeats, not only as regards the ambient world of other people and events, but also the private one of his own art and thought: "Myself must I remake / Till I am Timon and Lear / Or that William Blake...." So persistent was he in this work of transmutation, and so adept at it, that the ordinary affairs of daily life often must have seemed to him little more than a clumsy version of a truer, more intense life lived in the clarified world of his imagination. However that may have been for Yeats, it is certainly true for his readers: incidents, persons, squabbles with which or whom he was intermittently entangled increas ingly owe what importance they still have for us to the fact of occurring somewhere, caught and finalized, in the passionate world of his poems. -

Untitled.Pdf

STRUCTURE IN THE COLLECTED POEMS OF W. B. YEATS A Thesis Presented to the School of Graduate Studies Drake University In Partial Fulfil£ment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in English by Barbara L. Croft August 1970 l- ----'- _ u /970 (~ ~ 7cS"' STRUCTURE IN THE COLLECTED POEMS OF w. B. YEATS by Barbara L. Croft Approved by CGJmmittee: J4 .2fn., k ~~1""-'--- 7~~~ tI It t ,'" '-! -~ " -i L <_ j t , }\\ ) '~'l.p---------"'----------"? - TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter Page 1. INTRODUCTION ••••• . 1 2. COMPLETE OBJECTIVITY . • • . 23 3. THE DISCOVERY OF STRENGTH •••••••• 41 4. C~1PLETE SUBJECTIVITY •• • • • ••• 55 5. THE BREAKING OF STRENGTH ••••••••• 79 BIBLIOGRAPHY • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • 90 i1 CHAPTER I INTRODUCTION There is, needless to say, an abundance of criticism on W. B. Yeats. Obsessed with the peet's occultism, critics have pursued it to a depth which Yeats, a notedly poor scholar, could never have equalled; nor could he have matched their zeal for his politics. While it is not the purpose here to evaluate or even extensively to examine this criticism, two critics in particular, Richard Ellmann and John Unterecker, will preve especially valuable in this discussion. Ellmann's Yeats: ----The Man and The Masks is essentially a critical biography, Unterecker's ! Reader's Guide l! William Butler Yeats, while it uses biographical material, attempts to fecus upon critical interpretations of particular poems and groups of poems from the Collected Poems. In combination, the work of Ellmann and Unterecker synthesize the poet and his poetry and support the thesis here that the pattern which Yeats saw emerging in his life and which he incorporated in his work is, structurally, the same pattern of a death and rebirth cycle which he explicated in his philosophical book, A Vision. -

The Ironic Dialectic in Yeats

Colby Quarterly Volume 19 Issue 4 December Article 7 December 1983 The Ironic Dialectic in Yeats Lance Olsen Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.colby.edu/cq Recommended Citation Colby Library Quarterly, Volume 19, no.4, December 1983, p.215-220 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ Colby. It has been accepted for inclusion in Colby Quarterly by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ Colby. Olsen: The Ironic Dialectic in Yeats The Ironic Dialectic in Yeats by LANCE OLSEN UCH has been said about Yeats's mind working in terms of some M thing akin to the Hegelian dialectical triad in which a thesis and antithesis find resolution in a synthesis. Hegel, in whom Yeats was read ing widely by the middle of the 1920's, and toward whom the poet main tained a strong ambivalence throughout his life, would have it that it is in this dialectical triad "and in the comprehension of the unity of oppo sites, or of the positive in the negative, that speculative knowledge con sists."l But for Yeats the various sets of opposites he found in the world remained unresolved no matter how hard he fought toward resolution. In the running battle he had with them, he always failed to synthesize the diverse virtues in his many-sided debate with himself. The theses and antitheses with which he struggled never attained triadic unity. Instead, they survived as a series of clashing binaries: art/nature; youth/age; body/soul; passion/wisdom; beast/man; a Nietzschean Apollonian/ Dionysian; revelation /civilization; poetry/responsibility; time /eternity; being/becoming; the heroic/the non-heroic; and, finally, the ultimate dialectic between antitheses themselves and a Platonically ideal realm where antitheses in the end are annihilated. -

Literary Review

A BIRD’S EYE VIEW: EXPLORING THE BIRD IMAGERY IN THE LYRIC POETRY OF WILLIAM BUTLER YEATS By ERIN ELIZABETH RISNER A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate Studies Division of Ohio Dominican University Columbus, Ohio in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of MASTERS OF ARTS IN LIBERAL STUDIES MAY 2013 2 CERTIFICATION OF APPROVAL A BIRD’S EYE VIEW: EXPLORING THE BIRD IMAGERY IN THE LYRIC POETRY OF WILLIAM BUTLER YEATS By ERIN ELIZABETH RISNER Thesis Approved: _______________________________ ______________ Dr. Ronald W. Carstens, Ph.D. Date Professor of Political Science Chair, Liberal Studies Program ________________________________ ______________ Dr. Martin R. Brick, Ph.D. Date Assistant Professor of English _________________________________ ______________ Dr. Ann C. Hall, Ph. D. Date Professor of English 3 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I wish to express my appreciation to Dr. Martin Brick for all of his help and patience during this long, but rewarding, process. I also wish to thank Dr. Ann Hall for her final suggestions on this thesis and her Irish literature class two years ago that began this journey. A special thank you to Dr. Ron Carstens for his final review of this thesis and guidance through Ohio Dominican University’s MALS program. I must also give thanks to Dr. Beth Sutton-Ramspeck, who has guided me through academia since English Honors my freshman year at OSU-Lima. Final acknowledgements go to my family and friends. To my husband, Axle, thank you for all of your love and support the past three years. To my parents, Bob and Liz, I am the person I am today because of you. -

Predetermination and Nihilism in W. B. Yeats's Theatre

Revista Alicantina de Estudios Ingleses 5 (1992): 143-53 Predetermination and Nihilism in W. B. Yeats's Theatre Francisco Javier Torres Ribelles University of Alicante ABSTRACT This paper puts forward the hypothesis that Yeats's theatre is affected by a determinist component that governs it. This dependence is held to be the natural consequence of his desire to créate a universal art, a wish that confines the writer to a limited number of themes, death and oíd age being the most important. The paper also argües that the deter- minism is positive in the early stage but that it clearly evolves towards a negative kind. In spite of the playwright's acknowledged interest in doctrines related to the occult, the necessity of a more critical analysis is also put forward. The paper goes on to suggest that underlying the negative determinism of Yeats's late period there is a nihilistic view of life, of life after death and even of the work of art. The paper concludes by arguing that the poet may have exaggerated his pose as a response to his admitted inability to change the modern world and as a means of overcoming his sense of impending annihilation. The attitude underlying Yeats's earliest plays is radically opposed to what we find in the final ones. In the first stage, the determinism to which the subject matter inevitably leads is given a positive character by being adapted to the author's perspective. There is an emphasis on the power of art and a celebration of the Nietzschean-romantic valúes defended by the poet. -

Xerox University Microfilms 900 North Zaab Road Ann Arbor, Michigan 49100 Ll I!

INFORMATION TO USERS This material was produced from a microfilm copy of the original document. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality Is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. 1.The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a large round black mark, it is an indication that the photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during exposure and thus cause a blurred image. You will find a good (mage of the page in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., was part of the material being photographed the photographer followed a definite method in "sectioning" the material. It is customary to begin photoing at the upper left hand corner of a large sheet and to continue photoing from left to right in equal sections with a small overlap. If necessary, sectioning is continued again — beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. 4. The majority of users indicate that the textual content is of greatest value, however, a somewhat higher quality reproduction could be made from "photographs" if essential to the understanding of the dissertation. -

La Poesia Esoterica Del Periodo Simbolista E Modernista

1 UNIVERSITA’ DEGLI STUDI DI ROMA TRE DOTTORATO DI RICERCA IN CULTURE E LETTERATURE COMPARATE XXIV ciclo Identità per opposizione: Dio e uomo nella poesia di W. B. Yeats e Lucio Piccolo di Stefano Teatini TUTOR: Prof. Marinella Rocca Longo COORDINATORE: Prof. Francesco Fiorentino Desidero ringraziare la Prof.ssa Marinella Rocca Longo, la Prof.ssa Franca Ruggieri e La Dott.ssa Silvia Chessa per l’aiuto prestatomi nel contesto di questo lavoro e del mio percorso post-laurea in generale. Abstract. La tesi consiste, nella sua parte iniziale, in un’analisi della poesia di William Butler Yeats incentrata sul complesso rapporto tra uomo e Dio. Un forte accento è posto sul tema della morte, che costituiva evidentemente un problema cruciale per lo scrittore irlandese, come dimostrano le molte risorse da questi investite nell'elaborazione del sistema di A Vision. Il non essere era visto da Yeats come riconciliazione degli opposti, e l'essere (la vita) come affermazione del sé per opposizione: sono in quanto sono altro (motto in un certo senso vicino al "sono in quanto sono percepito" di George Berkeley). In questo studio verrà evidenziato il continuo oscillare del poeta di Sligo tra posizioni ‘primarie’ e ‘antitetiche’, oggettive e soggettive: tra rifiuto e accettazione, autoaffermazione e annullamento. Nei capitoli che concludono il volume sarà presentato uno studio sui legami tra Yeats e il siciliano Lucio Piccolo, relativamente agli argomenti affrontati nel corso delle sezioni precedenti dell’opera. 2 1.0 Introduzione. Il periodo di passaggio tra il XIX e il XX secolo fu caratterizzato da una diffusa riscoperta dell’occulto che si scatenò in tutto l’occidente. -

Yeats's “Sailing to Byzantium”: the Poetic Process of Impersonal Art

International Journal of Applied Linguistics & English Literature E-ISSN: 2200-3452 & P-ISSN: 2200-3592 www.ijalel.aiac.org.au Yeats’s “Sailing to Byzantium”: The Poetic Process of Impersonal Art S. Bharadwaj* Annamalai University, India Corresponding Author: S. Bharadwaj, E-mail: [email protected] ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Article history W.B.Yeats’s “Sailing to Byzantium” is a symbol of unity combining the realistic, intellectual, Received: March 13, 2018 emotional and mythical elements into a harmony; the harmony ensuing from a resolution of Accepted: May 23, 2018 conflicts or contending claims of his contemporaries, D.H.Lawrence and T.S.Eliot. All sorts of Published: September 01, 2018 existing critical perspectives on the most popular poem, though they provide “a greatly deepened Volume: 7 Issue: 5 understanding of Yeats,” are limited to either paraphrasal or aesthetic, biographical or holistic, Advance access: July 2018 spiritual or allusive, symbolic or technical level and they fail to read the text in the context of the pre-texts and the texts falling within its texture, in the light of other poems of Yeats and his contemporaries to bring out its totally different poetic structure and its single distinctive quality. Conflicts of interest: None This paper adopting an analytical inquiry into rhetoric of the poem, the play of meanings, filiations Funding: None among meanings and signs, substitutions and intertextuality, strives to uncover the difference within unity, the life-centric poetic process of Yeats’s impersonal art, his paradoxical structure of life-in-death for “perfection of life” of mortal man in contradistinction to his contemporaries’s death-centric structural concerns for “perfect work of art.” Key words: Paradox, Holistic, Irony, Arrogance, Magnificence, Erudite, Inherent and Callousness. -

Zoltán Farkas

Zoltán Farkas Sailing to (Yeats’) Byzantium „About Byzantium, W. B. Yeats proclaimed, „That is no country for old men”, and yet very largely we treat the history, the literature, the art of Byzantium as if it were made and experienced by, if not old, then mature people.”1 The sentence just quoted can be found in A Companion to Byzantium published in 2010. The author misquotes the very first line of a well-known poem written by the Irish poet, William Butler Yeats (1865–1939). The first line of the poem Sailing to Byzantium is, of course, That is no country for old men, but it definitely does not refer to Byzantium. Let us take a look at the four stanzas of Yeats’ famous poem. Sailing to Byzantium I That is no country for old men. The young In one another’s arms, birds in the trees, — Those dying generations — at their song, The salmon-falls, the mackerel-crowded seas, Fish, flesh, or fowl, commend all summer long Whatever is begotten, born and dies. Caught in that sensual music all neglect Monuments of unageing intellect. 1 The paper has been prepared with the financial help of the research project OTKA NN 104456. HENNE ss Y , C.: Young People in Byzantium. In: JAME S , L. (ed.): A Companion to Byzantium. (Blackwell Companions to the Ancient World) Chichester – Oxford 2010. 81. 316 Zoltán Farkas II An aged man is but a paltry thing, A tattered coat upon a stick, unless Soul clap its hands and sing, and louder sing For every tatter in its mortal dress, Nor is there singing school but studying Monuments of its own magnificence; And therefore I have sailed the seas and come To the holy city of Byzantium. -

Sailing to Byzantium: Pilgrimage of No Return by Thoithoi O’Cottage

Sailing To Byzantium: Pilgrimage of no Return by Thoithoi O’Cottage Written in 1926 (when Yeats was 61 years old) and first published in the collection The Tower in 1928, Sailing to Byzantium is hailed as one of Yeats’ greatest poems, and it explores time’s effect on all living things, making them slow down and lose their natural stamina and enthusiasm, how humans gain spiritual powers as physical ability slips away. The central concern of the poem is the dichotomies between youth and age, as well as sensuality and spirituality, and it finally tries to bring the opposites into one and end the conflict by creating an object which partakes of the nature of both natural and spiritual worlds. In fact, Yeats’ definition of art meshes natural and spiritual worlds together, and the song of the dying generations and the fixity of the artistic form build the basis of his concept of art. The poems tells about a man who, feeling past his prime and having come to the realization that youth and sensual life are no longer (though he allegedly liked) an option for him (That is no country for old men), sails off for a spiritual pilgrimage to the ideal world of Byzantium, a land where emphasis is not on the physical achievements of a person (monuments of unageing intellect). …I have sailed the seas and come To the holy city of Byzantium. Yeats felt that the civilization of Byzantium (a city on the shore of the Bosporus which on the emperor Constantine the Great’s triumph over it in AD 330 got renamed Constantinople and became the imperial capital of the Roman Empire and was again captured by the Ottoman Turks renaming it as Istanbul in 1453) represented a zenith in art, spirituality and philosophy. -

Download at No Cost Under the ‘Subscribe’ Tab on Our to Subscribers for an Annual Fee of $40

Volume 1, Issue 3 Fall 2015 1 READING THEIRELAND LITTLE MAGAZINE Table of Contents 02 Introduction Thomas Kinsella’s close reading of “The Tower,” by William Butler Yeats. Reprinted from Readings in Poetry Peppercanister 25 (2006), with permission of Thomas Kinsella 19 A Reader’s Guide to Thomas Kinsella by Adrienne Leavy 29 “Bringing it All Back Home with Seamus Heaney” by Yvonne Watterson 39 The Critical Commentary of Seamus Heaney by Adrienne Leavy 46 Spotlight on three new poetry titles from Irish Academic Press 49 Spotlight on two new poetry titles from Wake Forest University Press 50 Des Kenny reviews Gerald Dawe’s memoir, 1 The Stoic Man 52 New poem by Gerald Dawe 53 Ellen Birkett Morris reviews Nine Bright Shiners by Theo Dorgan 56 Little Magazine focus: Poetry Ireland Review no.116, Special Issue on W.B. Yeats Subscribe Every quarter, Reading Ireland will publish an E-Journal, Volume 1, issue 1 which appeared in Spring 2015 is available Reading Ireland: The Little Magazine, which will be available to download at no cost under the ‘subscribe’ tab on our to subscribers for an annual fee of $40. The magazine will website, www.readingireland.net, so that you as the reader be published in Spring, Summer, Autumn and Winter. The can decide if this is a publication you would like to receive aim of this publication is to provide in-depth analysis of on a quarterly basis. Irish literature, past and present, through a series of essays and articles written by myself and other Irish and American writers and academics, along with opening a window onto the best of contemporary Irish poetry, prose and drama.