Copyrighted Sarah Helen Youngblood

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Graham, Catherine, February 2006, Keep Rejects

Catherine Graham Collection: February 2006, 1. Krans, Horatio Sheafe, William Butler Yeats and the Irish Literary Revival. London: William Heinemann, 1905. 2. Moore, George, Confessions of a Young Man. London and Toronto: William Heinemann, 1935. 3. Meredith, George, A Reading of Life: With Other Poems. Westminster: Archibald Constable, 1901. 4. Synge, J.M., (Robin Skelton ed.), Some Sonnets from “Laura in Death” after the Italian of Frencesco Petrarch. Dolmen Eds. Dublin: Dolmen Press Ltd., 1971. 5. Skelton, Robin (ed.), The Collected Plays of Jack B. Yeats. Indianapolis and New York: Bobbs-Merrill Co., 1971. 6. Johnston, Denis, The Brazen Horn: A Non-Book for those, who, in revolt today, could be in command tomorrow. Dublin: Dolmen Press, 1976. 7. Skelton, Robin, An Irish Album. Dublin: Dolmen Press, 1969. 8. Montague, John, All Legendary Obstacles. Dublin: Dolmen Press, 1966. 9. Synge, J.M., My Wallet of Photographs. Dublin: Dolmen Press, 1971. 10. Clarke, Austin, Mnemosyne Lay in Dust. Dublin: Dolmen Press, 1966. 11. O’Grady, Desmond, The Gododdin. Dublin: Dolmen Press, 1977. 12. Bickley, Francis, J.M. Synge and the Irish Dramatic Movement. Toronto: Musson Book Co. 13. Horton, W.T. and W.B. Yeats, A Book of Images. London: Unicorn Press, 1898. 14. Yeats, W.B. (ed.), Beltaine: An Occasional Publication. Nos. 1, 2, 3, 1899-1900. London: Sign of the Unicorn, 1900. 15. Poems and Ballads of Young Ireland, 1888. Dublin: M.H. Gill and Son, 1888. 16. Moore, George, Heloise and Abelard. In two volumes, V.I. New York: Boni and Liveright, 1921. 17. Raine, Kathleen, Yeats, The Tarot and the Golden Dawn. -

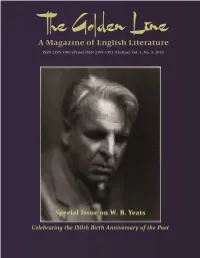

Online Version Available at Special Issue on WB Yeats Volume 1, Number 3, 2015

The Golden Line A Magazine of English Literature Online version available at www.goldenline.bcdedu.net Special Issue on W. B. Yeats Volume 1, Number 3, 2015 Guest-edited by Dr. Zinia Mitra Nakshalbari College, Darjeeling Published by The Department of English Bhatter College, Dantan P.O. Dantan, Dist. Paschim Medinipur West Bengal, India. PIN 721426 Phone: 03229-253238, Fax: 03229-253905 Website: www.bhattercollege.ac.in Email: [email protected] The Golden Line: A Magazine on English Literature Online version available at www.goldenline.bcdedu.net ISSN 2395-1583 (Print) ISSN 2395-1591 (Online) Inaugural Issue Volume 1, Number 1, 2015 Published by The Department of English Bhatter College, Dantan P.O. Dantan, Dist. Paschim Medinipur West Bengal, India. PIN 721426 Phone: 03229-253238, Fax: 03229-253905 Website: www.bhattercollege.ac.in Email: [email protected] © Bhatter College, Dantan Patron Sri Bikram Chandra Pradhan Hon’ble President of the Governing Body, Bhatter College Chief Advisor Pabitra Kumar Mishra Principal, Bhatter College Advisory Board Amitabh Vikram Dwivedi Assistant Professor, Shri Mata Vaishno Devi University, Jammu & Kashmir, India. Indranil Acharya Associate Professor, Vidyasagar University, West Bengal, India. Krishna KBS Assistant Professor in English, Central University of Himachal Pradesh, Dharamshala. Subhajit Sen Gupta Associate Professor, Department of English, Burdwan University. Editor Tarun Tapas Mukherjee Assistant Professor, Department of English, Bhatter College. Editorial Board Santideb Das Guest Lecturer, Department of English, Bhatter College Payel Chakraborty Guest Lecturer, Department of English, Bhatter College Mir Mahammad Ali Guest Lecturer, Department of English, Bhatter College Thakurdas Jana Guest Lecturer, Bhatter College ITI, Bhatter College External Board of Editors Asis De Assistant Professor, Mahishadal Raj College, Vidyasagar University. -

Poetry, Place, and Spiritual Practices by Katharine Bubel BA, Trinity

Edge Effects: Poetry, Place, and Spiritual Practices by Katharine Bubel B.A., Trinity Western University, 2004 M.A., Trinity Western University, 2009 A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of English Katharine Bubel, 2018 University of Victoria All rights reserved. This dissertation may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without the permission of the author. ii Supervisory Committee Edge Effects: Poetry, Place, and Spiritual Practices by Katharine Bubel B.A., Trinity Western University, 2004 M.A., Trinity Western University, 2009 Supervisory Committee Dr. Nicholas Bradley, Department of English Supervisor Dr. Magdalena Kay, Department of English Departmental Member Dr. Iain Higgins, Department of English Departmental Member Dr. Tim Lilburn, Department of Writing Outside Member iii Abstract "Edge Effects: Poetry, Place, and Spiritual Practices” focusses on the intersection of the environmental and religious imaginations in the work of five West Coast poets: Robinson Jeffers, Theodore Roethke, Robert Hass, Denise Levertov, and Jan Zwicky. My research examines the selected poems for their reimagination of the sacred perceived through attachments to particular places. For these writers, poetry is a constitutive practice, part of a way of life that includes desire for wise participation in the more-than-human community. Taking into account the poets’ critical reflections and historical-cultural contexts, along with a range of critical and philosophical sources, the poetry is examined as a discursive spiritual exercise. It is seen as conjoined with other focal practices of place, notably meditative walking and attentive looking and listening under the influence of ecospiritual eros. -

W. B. Yeats Selected Poems

W. B. Yeats Selected Poems Compiled by Emma Laybourn 2018 This is a free ebook from www.englishliteratureebooks.com It may be shared or copied for any non-commercial purpose. It may not be sold. Cover picture shows Ben Bulben, County Sligo, Ireland. Contents To return to the Contents list at any time, click on the arrow ↑ before each poem. Introduction From The Wanderings of Oisin and other poems (1889) The Song of the Happy Shepherd The Indian upon God The Indian to his Love The Stolen Child Down by the Salley Gardens The Ballad of Moll Magee The Wanderings of Oisin (extracts) From The Rose (1893) To the Rose upon the Rood of Time Fergus and the Druid The Rose of the World The Rose of Battle A Faery Song The Lake Isle of Innisfree The Sorrow of Love When You are Old Who goes with Fergus? The Man who dreamed of Faeryland The Ballad of Father Gilligan The Two Trees From The Wind Among the Reeds (1899) The Lover tells of the Rose in his Heart The Host of the Air The Unappeasable Host The Song of Wandering Aengus The Lover mourns for the Loss of Love He mourns for the Change that has come upon Him and his Beloved, and longs for the End of the World He remembers Forgotten Beauty The Cap and Bells The Valley of the Black Pig The Secret Rose The Travail of Passion The Poet pleads with the Elemental Powers He wishes his Beloved were Dead He wishes for the Cloths of Heaven From In the Seven Woods (1904) In the Seven Woods The Folly of being Comforted Never Give All the Heart The Withering of the Boughs Adam’s Curse Red Hanrahan’s Song about Ireland -

Shadows Deep: Change and Continuity in Yeats

Colby Quarterly Volume 22 Issue 4 December Article 3 December 1986 Shadows Deep: Change and Continuity in Yeats Donald Pearce Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.colby.edu/cq Recommended Citation Colby Library Quarterly, Volume 22, no.4, December 1986, p.198-204 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ Colby. It has been accepted for inclusion in Colby Quarterly by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ Colby. Pearce: Shadows Deep: Change and Continuity in Yeats Shadows Deep: Change and Continuity in Yeats by DONALD PEARCE He made songs because he had a will to make songs and not because love moved him thereto. Ue de Saint-eire VERY POET is, at bottom, a kind of alchemist, every poem an ap E paratus for transn1uting the "base metal" of life into the gold of art. Especially is this true of Yeats, not only as regards the ambient world of other people and events, but also the private one of his own art and thought: "Myself must I remake / Till I am Timon and Lear / Or that William Blake...." So persistent was he in this work of transmutation, and so adept at it, that the ordinary affairs of daily life often must have seemed to him little more than a clumsy version of a truer, more intense life lived in the clarified world of his imagination. However that may have been for Yeats, it is certainly true for his readers: incidents, persons, squabbles with which or whom he was intermittently entangled increas ingly owe what importance they still have for us to the fact of occurring somewhere, caught and finalized, in the passionate world of his poems. -

Yeats, Bloom, and the Dialectics of Theory, Criticism, and Poetry

Yeats, Bloom, and the Dialectics of Theory, Criticism, and Poetry by Steven J. Skelley, MA ~:~.:.; .. "<f./ -, '\ .> t.(r{"ri'"'1 I ... <.. II- -. ' Thesis submitted to the University of Nottingham for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, October 1992 Acknowledgments To my supervisors, Dr. Bernard McGuirk (Hispanic Studies and Critical Theory) and Dr. David Murray (American Studies and Head of Postgraduate School of Critical Theory), lowe a great debt of gratitude for their enthusiasm for this proj ect. Their intellectual and practical support was priceless, and their cooperation with each other and with me never failed as a model of supervisorial expertise. All PhD candidates ought to be blessed with such supervision. I also wish to thank Dr. Douglas Tallack (American Studies and former Head of the School of Cri tical Theory) for his encouragement both intellectual and administrative towards the successful completion of this project. To the PhD students and to the supervisorial staff who attended work-in-progress seminars in the School of Critical Theory, and who offered so many helpful comments, suggestions, and opinions, I also give thanks. The staff of the Hallward Library must not go unmentioned, for their fine and courteous assistance throughout these four years. Dedication This dissertation is dedicated to my epipsyche and muse, Hala Darwish, whose inspirational presence in my heart was, it may be said, the magic within these evasions, these wanderings . Until one day I met a star that burned Bright in the heart of my heavenly breast, And then I knew why I was who I was, And why my soul would be forever lost In the folds of her voice raging in my veins SJS, August 1992 ABSTRACT This thesis begins by showing how a strong and subtle challenge to poetry and theories of poetry has been recently argued by writers like Paul de Man and J. -

YEATS ANNUAL No. 18 Frontispiece: Derry Jeffares Beside the Edmund Dulac Memorial Stone to W

To access digital resources including: blog posts videos online appendices and to purchase copies of this book in: hardback paperback ebook editions Go to: https://www.openbookpublishers.com/product/194 Open Book Publishers is a non-profit independent initiative. We rely on sales and donations to continue publishing high-quality academic works. In the same series YEATS ANNUALS Nos. 1, 2 Edited by Richard J. Finneran YEATS ANNUALS Nos. 3-8, 10-11, 13 Edited by Warwick Gould YEATS AND WOMEN: YEATS ANNUAL No. 9: A Special Number Edited by Deirdre Toomey THAT ACCUSING EYE: YEATS AND HIS IRISH READERS YEATS ANNUAL No. 12: A Special Number Edited by Warwick Gould and Edna Longley YEATS AND THE NINETIES YEATS ANNUAL No. 14: A Special Number Edited by Warwick Gould YEATS’S COLLABORATIONS YEATS ANNUAL No. 15: A Special Number Edited by Wayne K. Chapman and Warwick Gould POEMS AND CONTEXTS YEATS ANNUAL No. 16: A Special Number Edited by Warwick Gould INFLUENCE AND CONFLUENCE: YEATS ANNUAL No. 17: A Special Number Edited by Warwick Gould YEATS ANNUAL No. 18 Frontispiece: Derry Jeffares beside the Edmund Dulac memorial stone to W. B. Yeats. Roquebrune Cemetery, France, 1986. Private Collection. THE LIVING STREAM ESSAYS IN MEMORY OF A. NORMAN JEFFARES YEATS ANNUAL No. 18 A Special Issue Edited by Warwick Gould http://www.openbookpublishers.com © 2013 Gould, et al. (contributors retain copyright of their work). The text of this book is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported Licence. This licence allows you to share, copy, distribute and transmit the text; to adapt the text and to make commercial use of the text. -

Protestants Reading Catholicism: Crashaw's Reformed Readership

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University English Theses Department of English 8-14-2009 Protestants Reading Catholicism: Crashaw's Reformed Readership Andrew Dean Davis Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/english_theses Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Davis, Andrew Dean, "Protestants Reading Catholicism: Crashaw's Reformed Readership." Thesis, Georgia State University, 2009. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/english_theses/69 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of English at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in English Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. PROTESTANTS READING CATHOLICISM: CRASHAW’S REFORMED READERSHIP by ANDREW D. DAVIS Under the direction of Dr. Paul Voss ABSTRACT This thesis seeks to realign Richard Crashaw’s aesthetic orientation with a broadly conceptualized genre of seventeenth-century devotional, or meditative, poetry. This realignment clarifies Crashaw’s worth as a poet within the Renaissance canon and helps to dismantle historicist and New Historicist readings that characterize him as a literary anomaly. The methodology consists of an expanded definition of meditative poetry, based primarily on Louis Martz’s original interpretation, followed by a series of close readings executed to show continuity between Crashaw and his contemporaries, not discordance. The thesis concludes by expanding the genre of seventeenth-century devotional poetry to include Edward Taylor, who despite his Puritanism, also exemplifies many of the same generic attributes as Crashaw. INDEX WORDS: Richard Crashaw, Edward Taylor, Steps to the Temple , Metaphysical poets, Catholicism, Puritans, New Historicism, Meditative poetry, Louis Martz, Genre Theory PROTESTANTS READING CATHOLICISM: CRASHAW’S REFORMED READERSHIP by ANDREW D. -

Untitled.Pdf

STRUCTURE IN THE COLLECTED POEMS OF W. B. YEATS A Thesis Presented to the School of Graduate Studies Drake University In Partial Fulfil£ment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in English by Barbara L. Croft August 1970 l- ----'- _ u /970 (~ ~ 7cS"' STRUCTURE IN THE COLLECTED POEMS OF w. B. YEATS by Barbara L. Croft Approved by CGJmmittee: J4 .2fn., k ~~1""-'--- 7~~~ tI It t ,'" '-! -~ " -i L <_ j t , }\\ ) '~'l.p---------"'----------"? - TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter Page 1. INTRODUCTION ••••• . 1 2. COMPLETE OBJECTIVITY . • • . 23 3. THE DISCOVERY OF STRENGTH •••••••• 41 4. C~1PLETE SUBJECTIVITY •• • • • ••• 55 5. THE BREAKING OF STRENGTH ••••••••• 79 BIBLIOGRAPHY • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • 90 i1 CHAPTER I INTRODUCTION There is, needless to say, an abundance of criticism on W. B. Yeats. Obsessed with the peet's occultism, critics have pursued it to a depth which Yeats, a notedly poor scholar, could never have equalled; nor could he have matched their zeal for his politics. While it is not the purpose here to evaluate or even extensively to examine this criticism, two critics in particular, Richard Ellmann and John Unterecker, will preve especially valuable in this discussion. Ellmann's Yeats: ----The Man and The Masks is essentially a critical biography, Unterecker's ! Reader's Guide l! William Butler Yeats, while it uses biographical material, attempts to fecus upon critical interpretations of particular poems and groups of poems from the Collected Poems. In combination, the work of Ellmann and Unterecker synthesize the poet and his poetry and support the thesis here that the pattern which Yeats saw emerging in his life and which he incorporated in his work is, structurally, the same pattern of a death and rebirth cycle which he explicated in his philosophical book, A Vision. -

Hermetic Philosophy and Dual Selfhood in Yeats's

“An Image of Mysterious Wisdom”: Hermetic Philosophy and Dual Selfhood in Yeats’s Poetic Dialogues Treball de Fi de Grau/ BA dissertation Author: Paula Moschini Izquierdo Supervisor: Jordi Coral Escolà Departament de Filologia Anglesa i de Germanística Grau d’Estudis Anglesos June 2018 CONTENTS 0. Introduction ...................................................................................................................... 1 0.1. Methodology and Analysed Concepts ................................................................................... 1 0.2. Yeats and Philosophy: The Self and the Antinomies ......................................................... 2 0.3. The Hermetic Dialogue ............................................................................................................. 7 0.4. The Aesthetics of Artistic Reinterpretation: The Symbol ................................................ 9 1. Ego Dominus Tuus ....................................................................................................... 10 1.1. The Tower as a Symbol for the Self and “the Image” ..................................................... 11 1.2. Unity of Being in Artists ......................................................................................................... 14 1.3. A Poem about the Necessity of the Intuitive Wisdom in Poetry ................................... 16 2. A Dialogue of Self and Soul ........................................................................................ 18 2.1. Love and War: The Eternal -

Yeats As Precursor Readings in Irish, British And

Yeats as Precursor Readings in Irish, British and American Poetry Steven Matthews Yeats as Precursor Copyright material from www.palgraveconnect.com - licensed to Universitetsbiblioteket i Tromso - PalgraveConnect - 2011-03-18 - PalgraveConnect Tromso i - licensed to Universitetsbiblioteket www.palgraveconnect.com material from Copyright 10.1057/9780230599482 - Yeats as Precursor, Steven Matthews Also by Steven Matthews IRISH POETRY: Politics, History, Negotiation LES MURRAY (forthcoming) REWRITING THE THIRTIES: Modernism and After (co-editor with Keith Williams) Copyright material from www.palgraveconnect.com - licensed to Universitetsbiblioteket i Tromso - PalgraveConnect - 2011-03-18 - PalgraveConnect Tromso i - licensed to Universitetsbiblioteket www.palgraveconnect.com material from Copyright 10.1057/9780230599482 - Yeats as Precursor, Steven Matthews Yeats as Precursor Readings in Irish, British and American Poetry Steven Matthews Copyright material from www.palgraveconnect.com - licensed to Universitetsbiblioteket i Tromso - PalgraveConnect - 2011-03-18 - PalgraveConnect Tromso i - licensed to Universitetsbiblioteket www.palgraveconnect.com material from Copyright 10.1057/9780230599482 - Yeats as Precursor, Steven Matthews First published in Great Britain 2000 by MACMILLAN PRESS LTD Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire RG21 6XS and London Companies and representatives throughout the world A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. ISBN 0–333–71147–5 First published in the United States of America 2000 by ST. MARTIN’S PRESS, INC., Scholarly and Reference Division, 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10010 ISBN 0–312–22930–5 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Matthews, Steven, 1961– Yeats as precursor : readings in Irish, British, and American poetry / Steven Matthews. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0–312–22930–5 1. -

The Art of William Butler and Jack Yeats. Artsedge Curricula, Lessons and Activities

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 477 330 CS 511 355 AUTHOR Karsten, Jayne TITLE Magic Words, Magic Brush: The Art of William Butler and Jack Yeats. ArtsEdge Curricula, Lessons and Activities. INSTITUTION John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts, Washington, DC. SPONS AGENCY National Endowment for the Arts (NFAH), Washington, DC.; MCI WorldCom, Arlington, VA.; Department of Education, Washington, DC. PUB DATE 2002-00-00 NOTE 25p. AVAILABLE FROM For full text: http://artsedge.kennedy-center.org/ teaching_materials/curricula/curricula.cfm?subject_id=LNA. PUB TYPE Guides Classroom Teacher (052) EDRS PRICE EDRS Price MF01/PCO2 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Art Expression; Class Activities; *Classroom Techniques; *Cultural Context; *Foreign Countries; Interdisciplinary Approach; Learning Activities; *Poetry; Secondary Education; Student Educational Objectives; Teacher Developed Materials; Units of Study IDENTIFIERS Ireland; *Yeats (William Butler) ABSTRACT This curriculum unit, designed for grades 7-12, integrates various artistic disciplines with geography, history, social studies, media, and technology. This unit on William Butler Yeats, the writer, and Jack Yeats, the painter, seeks to immerse students in a study of the brothers as voices of Ireland and as two of the most renowned artists of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The unit is dedicated also to helping students see how the outlook of an age controls cultural expression, and how this expression is articulated in similar ways throughout genres of art. To help effect these major goals, focus in the unit is placed on: the impact of geography, place, and family on both William Butler Yeats and Jack Yeats; the influence of personalities of the time period on the two artists;.