In Public-Private Partnerships: Reading the Cultural Heritage Management Practices of Turkey

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

University of Cincinnati

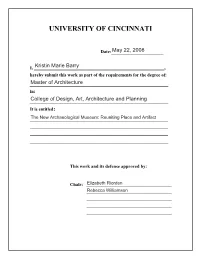

UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI Date:___________________May 22, 2008 I, _________________________________________________________,Kristin Marie Barry hereby submit this work as part of the requirements for the degree of: Master of Architecture in: College of Design, Art, Architecture and Planning It is entitled: The New Archaeological Museum: Reuniting Place and Artifact This work and its defense approved by: Chair: _______________________________Elizabeth Riorden _______________________________Rebecca Williamson _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ The New Archaeological Museum: Reuniting Place and Artifact Kristin Barry Bachelor of Science in Architecture University of Cincinnati May 30, 2008 Submittal for Master of Architecture Degree College of Design, Art, Architecture and Planning Prof. Elizabeth Riorden Abstract Although various resources have been provided at archaeological ruins for site interpretation, a recent change in education trends has led to a wider audience attending many international archaeological sites. An innovation in museum typology is needed to help tourists interpret the artifacts that been found at the site in a contextual manner. Through a study of literature by experts such as Victoria Newhouse, Stephen Wells, and other authors, and by analyzing successful interpretive center projects, I have developed a document outlining the reasons for on-site interpretive centers and their functions and used this material in a case study at the site of ancient Troy. My study produced a research document regarding museology and design strategy for the physical building, and will be applicable to any new construction on a sensitive site. I hope to establish a precedent that sites can use when adapting to this new type of visitors. iii Acknowledgements I would like to thank a number of people for their support while I have been completing this program. -

Rising Economy of Konya

Konya is the capital of; birth of humanity by Çatalhöyük, Anadolu Seljuk Empire by hospitality, tolerance by Mevlana (Rumi), education and culture by deep rooted history, industry and commerce by strong economy. Konya is the centre of agriculture, commerce, industry and tourism in both Turkiye and Central Anatolian Region as a locomotive for other cities. Konya is very important manufacturing base in Turkiye. TOP REASONS TO INVEST IN KONYA FOCUSED SECTORS AGRICULTURE & LIVESTOCK INDUSTRIAL INFRASTRUCTURE UPCOMING PROJECTS WHY KONYA? TOP REASONS TO INVEST IN KONYA Top Reasons to Invest In Konya Konya is the largest city in Turkey with 38.873 km2 area. İSTANBUL İZMİR KONYA Comes 7th in Turkey with 2.161.303 population. (2,7% of Turkey’s Population) Top Reasons to Invest In Konya YOUNG POPULATION Potential of the Konya Economy - Young Population - Population-Age Groups Graph 10,0 9,4 8,7 8,9 8,9 8,7 9,0 8,5 8,0 7,5 7,1 7,0 6,3 6,1 6,0 5,0 5,0 4,1 4,0 3,5 3,0 2,4 2,0 2,0 1,7 0,9 1,0 0,3 0,1 0,0 0-4 5-9 90+ 10-14 15-19 20-24 25-29 30-34 35-39 40-44 45-49 50-54 55-59 60-64 65-69 70-74 75-79 80-84 85-89 ✓60,6 % of the population is below 35 Source: TURKSTAT Konya has the lowest unemployment rate in Turkey. Unemployment Rate/ Konya - Turkey (%) 16 14 14 Konya Gıda ve Tarım Üniversitesi 11,9 12 11 10,9 11,1 9,8 9,9 10,3 9,2 9,7 10 10,7 10,8 8 8,2 6 6,9 6,2 6,5 6,5 5,6 6,1 4 4,7 2 0 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 Turkey Konya CENTER OF ANATOLIA… Ability to reach more than 10 million people in 3 hours by land… (Ankara, Antalya ,Cappadocia) Railway connection to major cities…(İstanbul, Ankara, İzmir, Adana, Mersin) Konya-Ankara travel takes 1 hour 30 minutes with high speed train… Konya-Eskişehir travel takes 1 hour 50 minutes with high speed train… Konya-İstanbul travel takes 4 hours 15 minutes with high speed train… 4 hours to the biggest harbour (Mersin) of Turkey… AIRWAY CONNECTION -Daily flights between İstanbul-Konya and İzmir-Konya periodic flights. -

GAZİANTEP ZEUGMA MOZAİK MÜZESİ We Have a New Museum: Gaziantep Zeugma Mozaic Museum

EKİM-KASIM-ARALIK 2011 OCTOBER-NOVEMBER-DECEMBER 2011 SAYI 3 ISSUE 3 Yeni bir müzemiz oldu: GAZİANTEP ZEUGMA MOZAİK MÜZESİ We have a new museum: Gaziantep Zeugma Mozaic Museum KÜLTÜRE ve SANATA CAN SUYU: DÖSİMM Life line support for history, culture and art: DÖSİMM TOKAT ATATÜRK EVİ ve Etnografya Müzesi The Atatürk House and Etnographic Museum in Tokat Başarısını talanıyla gölgeleyen SCHLIEMANN Schliemann who overshadowed his success with his pillage MEDUSA: Mitolojinin yılan saçlı kahramanı Medusa: Mythological heroine with snakes for hair İSTANBUL ARKEOLOJİ MÜZELERİ KOLEKSİYONUNDAN IYI ÇOBAN ISA İyi Çoban İsa ensesine oturttuğu koçun ayaklarını sağ eli ile tutmuştur. Kısa bir tunik giymiş olup giysisini belinden bir kuşakla bağlamıştır. Başını yukarı doğru kaldırmıştır. Kısa dalgalı saçları yüzünü çevirmektedir. Sırtındaki koçun anatomik yapısı çok iyi işlenmiştir. Ana Sponsor İstanbul Arkeoloji Müzeleri TÜRSAB’ın desteğiyle yenileniyor İstanbul Arkeoloji Müzeleri Osman Hamdi Bey Yokuşu Sultanahmet İstanbul • Tel: 212 527 27 00 - 520 77 40 • www.istanbularkeoloji.gov.tr EKİM-KASIM-ARALIK 2011 OCTOBER-NOVEMBER-DECEMBER 2011 SAYI 3 ISSUE 3 Yeni bir müzemiz oldu: GAZİANTEP ZEUGMA içindekiler MOZAİK MÜZESİ We have a new museum: Gaziantep Zeugma Mozaic Museum KÜLTÜRE ve SANATA CAN SUYU: DÖSİMM Life line support for history, culture and art: DÖSİMM TOKAT ATATÜRK EVİ ve Etnografya Müzesi The Atatürk House and Etnographic Museum in Tokat Başarısını talanıyla gölgeleyen SCHLIEMANN Schliemann who overshadowed his success with his pillage MEDUSA: Mitolojinin yılan saçlı kahramanı Medusa: Mythological heroine with snakes for hair 5 Başyazı Her taşı bir tarih sahnesi 22 Dünya tarihinin ev sahibi BRITISH MUSEUM 8 36 KÜLTÜRE ve SANATA can suyu 46 Taşa çeviren bakışlar Tarihin AYAK İZLERİ.. -

A Sustainable View to Fener ‐ Balat District

Papers A Sustainable View to Fener ‐ Balat District Kishali E. Politecnico di Milano, Building Environment Science Technology (BEST) [email protected] Grecchi M. Politecnico di Milano, Building Environment Science Technology (BEST) [email protected] TRADITIONAL TECHNIQUES AND DISTRICT REHABILITATION Sustainable rehabilitation and preservation strategies in historic quarters Industrialisation, started with Industrial Revolution in mid 18th century by the invention of machines but advanced fast in early 19th century by establishing factories in large areas, has changed various aspects of life in terms of economy, architecture, design, and construction, rate of production, social life and politics. However one aspect, the nature, became very important in architecture field when there have been various and serious problems on four basic elements of planet: earth, air, water and fire. All these elements have been influenced badly after industrialisation period due to high demand for rapid and heavy construction regarding the all aspects above. Nowadays, in architecture it is inevitable to find a link between nature and construction, engineering and design to preserve the resources of life which can be called sustainability. This link is very essential in today's new architectural designs to sustain environment but it is more interesting and difficult to find the sustainable link for historical buildings which were constructed during economical revolutions. The structures were constructed with peculiar technology, serviceability in its own environment and definite district, as the time passes the possibility to withstand changing environment conditions would become complicated. In this paper, historical residential buildings, constructed in 19th century in Fener – Balat Istanbul, Turkey, an important example of cultural heritage district, will be analysed in terms of three different views. -

Advocacy Planning in Urban Renewal: Sulukule Platform As the First Advocacy Planning Experience of Turkey

Advocacy Planning in Urban Renewal: Sulukule Platform As the First Advocacy Planning Experience of Turkey A thesis submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Community Planning of the College of Design, Architecture, Art, and Planning by Albeniz Tugce Ezme Bachelor of City and Regional Planning Mimar Sinan Fine Arts University, Istanbul, Turkey January 2009 Committee Chair: Dr. David Varady Submitted February 19, 2014 Abstract Sulukule was one of the most famous neighborhoods in Istanbul because of the Romani culture and historic identity. In 2006, the Fatih Municipality knocked on the residents’ doors with an urban renovation project. The community really did not know how they could retain their residence in the neighborhood; unfortunately everybody knew that they would not prosper in another place without their community connections. They were poor and had many issues impeding their livelihoods, but there should have been another solution that did not involve eviction. People, associations, different volunteer groups, universities in Istanbul, and also some trade associations were supporting the people of Sulukule. The Sulukule Platform was founded as this predicament began and fought against government eviction for years. In 2009, the area was totally destroyed, although the community did everything possible to save their neighborhood through the support of the Sulukule Platform. I cannot say that they lost everything in this process, but I also cannot say that anything was won. I can only say that the Fatih Municipality soiled its hands. No one will forget Sulukule, but everybody will remember the Fatih Municipality with this unsuccessful project. -

Abstracts-Booklet-Lamp-Symposium-1

Dokuz Eylül University – DEU The Research Center for the Archaeology of Western Anatolia – EKVAM Colloquia Anatolica et Aegaea Congressus internationales Smyrnenses XI Ancient terracotta lamps from Anatolia and the eastern Mediterranean to Dacia, the Black Sea and beyond. Comparative lychnological studies in the eastern parts of the Roman Empire and peripheral areas. An international symposium May 16-17, 2019 / Izmir, Turkey ABSTRACTS Edited by Ergün Laflı Gülseren Kan Şahin Laurent Chrzanovski Last update: 20/05/2019. Izmir, 2019 Websites: https://independent.academia.edu/TheLydiaSymposium https://www.researchgate.net/profile/The_Lydia_Symposium Logo illustration: An early Byzantine terracotta lamp from Alata in Cilicia; museum of Mersin (B. Gürler, 2004). 1 This symposium is dedicated to Professor Hugo Thoen (Ghent / Deinze) who contributed to Anatolian archaeology with his excavations in Pessinus. 2 Table of contents Ergün Laflı, An introduction to the ancient lychnological studies in Anatolia, the eastern Mediterranean, Dacia, the Black Sea and beyond: Editorial remarks to the abstract booklet of the symposium...................................6-12. Program of the international symposium on ancient lamps in Anatolia, the eastern Mediterranean, Dacia, the Black Sea and beyond..........................................................................................................................................12-15. Abstracts……………………………………...................................................................................16-67. Constantin -

An Interpretation of Some Unpublished in Situ and Recorded Rum Seljuk 13Th C. External and Internal Figural Relief Work on the Belkıs (Aspendos) Palace, Antalya

GEPHYRA 8 2011 143–184 Terrance Michael Patrick DUGGAN An interpretation of some unpublished in situ and recorded Rum Seljuk 13th c. external and internal figural relief work on the Belkıs (Aspendos) Palace, Antalya Abstract: This article is divided into four parts. Firstly, it notes the precedent provided by the conversion of the Roman theatre at Bosra in Syria into an Ayyubid Palace, for the conversion of the Roman theater into the Rum Seljuk palace at Belkis–Aspendos and the known extensive use made of Syrian trained architects for important architectural projects by Rum Seljuk Sul- tans in the first half of the 13th c. Secondly, the two bands of Seljuk low relief depictions of fe- lines and a deer on a series of re–carved Roman limestone blocks on the exterior wall by the door leading to the southern köşk–pavilion erected above the parados and upon the lintel over this door, discovered by the author in 2007, extending over a length of nearly 10 m are de- scribed and the deliberate pecking of the surface of these low relief depictions it is suggested, was to provide bonding for applied painted stucco carved relief–work that completed this relief work on the exterior palace facade. The third section describes the painted Seljuk tympanum relief sculpture made of stucco plaster that concealed the Roman relief carving of Dionysus in the pediment of the sceanae frons in the 13th c. A sculptural relief depiction of a nude female figure which was fortunately recorded by Charles Texier early in the 19th c. -

National Roma Integration Strategies

err C EUROPEAN ROMA RIGHTS CENTRE The European Roma Rights Centre (ERRC) is an international public interest law organisation working to combat anti- Roma Rights Romani racism and human rights abuse of Roma. The approach of the ERRC involves strategic litigation, international Journal of the european roma rights Centre advocacy, research and policy development and training of Romani activists. The ERRC has consultative status with the Council of Europe, as well as with the Economic and Social Council of the United Nations. The ERRC has been the recipient of numerous awards for its efforts to advance human rights respect of Roma: The 2013 PL Foundation Freedom Prize; the 2012 Stockholm Human Rights Award, awarded jointly to the ERRC and Tho- mas Hammarberg; in 2010, the Silver Rose Award of SOLIDAR; in 2009, the Justice Prize of the Peter and Patricia Gruber Foundation; in 2007, the Max van der Stoel Award given by the High Commissioner on National Minorities and the Dutch Foreign Ministry; and in 2001, the Geuzenpenning Award (the Geuzen medal of honour) by Her Royal Highness Princess Margriet of the Netherlands; Board of Directors Robert Kushen – (USA - Chair of the Board) | Dan Pavel Doghi (Romania) | James A. Goldston (USA) | Maria Virginia Bras Gomes (Portugal) | Jeno˝ Kaltenbach (Hungary) I Abigail Smith, ERRC Treasurer (USA) Executive Director Dezideriu Gergely Staff Adam Weiss (Legal Director) | Andrea Jamrik (Financial Officer) | Andrea Colak (Lawyer) | Anna Orsós (Pro- grammes Assistant) | Anca Sandescu (Human Rights Trainer) -

Roma and Representative Justice in Turkey

Roma and representative justice in Turkey Basak Akkan This Working Paper was written within the framework of Work Package 5 (justice as lived experience) for Deliverable 5.2 (comparative report on the tensions between institutionalized political justice and experienced (mis)recognition) July 2018 Funded by the Horizon 2020 Framework Programme of the European Union Acknowledgements I would like to express my gratitude to the participants of the research who genuinely shared their views. I would also like to express my thanks to Bridget Anderson and Pier-Luc Dupont for their comments on the earlier version of this report. Want to learn more about what we are working on? Visit us at: Website: https://ethos-europe.eu Facebook: www.facebook.com/ethosjustice/ Blog: www.ethosjustice.wordpress.com Twitter: www.twitter.com/ethosjustice Hashtag: #ETHOSjustice Youtube: www.youtube.com/ethosjustice European Landscapes of Justice (web) app: http://myjustice.eu/ This publication has been produced with the financial support of the Horizon 2020 Framework Programme of the European Union. The contents of this publication are the sole responsibility of the authors and can in no way be taken to reflect the views of the European Commission. Copyright © 2018, ETHOS consortium – All rights reserved ETHOS project The ETHOS project has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under grant agreement No. 727112 2 About ETHOS ETHOS - Towards a European THeory Of juStice and fairness is a European Commission Horizon 2020 research project that seeks to provide building blocks for the development of an empirically informed European theory of justice and fairness. -

The Influences of the Interactive Systems on Museum Visitors’ Experience: a Comparative Study from Turkey

JOURNAL OF TOURISM INTELLIGENCE AND SMARTNESS Year (Yıl): 2019 Volume (Cilt): 2 Issue (Sayı): 1 Pages (Sayfa): 27/38 THE INFLUENCES OF THE INTERACTIVE SYSTEMS ON MUSEUM VISITORS’ EXPERIENCE: A COMPARATIVE STUDY FROM TURKEY Assist. Prof. Sebahattin Emre DİLEK1 Batman University, School of Tourism and Hotel Management, Turkey E-mail: [email protected] ORCID: 0000-0001-7830-1928 Assoc. Prof. Mustafa DOĞAN Batman University, School of Tourism and Hotel Management, Turkey E-mail: [email protected] ORCID: 0000-0001-7648-8469 Prof. Dr. Gülriz KOZBE Batman University, Faculty of Science and Letters, Department of Art History, Turkey E-mail: [email protected] ORCID: 0000-0002-4727-3052 Abstract To the effect, technologically advanced interactive systems, settled in modern-day museums research new ways to offer a Article Info: positive experience to the visitors and encourage them to return, using modern communication and learning tools. This paper Received: 30-04-2019 examines user interaction applications of a recent digital cultural Accepted: 07-05-2019 heritage exploration project concerning of the most popular three museums (Mardin, Şanlıurfa, Gaziantep Museums) that are located in different cities of the southeast region of Turkey. The project aims at enriching the visitor experiences through modern digital technologies. Main modules include 3D scanning of the artifacts, information screens and mobile interaction with Augmented Reality (AR). In this paper, it is explored and Keywords: compared the visitor perceptions and experiences for three Museum, museums. For this purpose, two scales were used for data Interactive Systems, collection. In accordance with the first aim of the study, the scale Augmented Reality, adapted by Chung, Han & Joun (2015) which is to explain Visitor Experience, visitors’ acceptance of based on the interactive systems. -

The Hagia Sophia in Its Urban Context: an Interpretation of the Transformations of an Architectural Monument with Its Changing Physical and Cultural Environment

THE HAGIA SOPHIA IN ITS URBAN CONTEXT: AN INTERPRETATION OF THE TRANSFORMATIONS OF AN ARCHITECTURAL MONUMENT WITH ITS CHANGING PHYSICAL AND CULTURAL ENVIRONMENT A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate School of Engineering and Sciences of İzmir Institute of Technology in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE in Architecture by Nazlı TARAZ August 2014 İZMİR We approve the thesis of Nazlı TARAZ Examining Committee Members: ___________________________ Assist. Prof. Dr. Zeynep AKTÜRE Department of Architecture, İzmir Institute of Technology _____________________________ Assist. Prof. Dr. Ela ÇİL SAPSAĞLAM Department of Architecture, İzmir Institute of Technology ___________________________ Dr. Çiğdem ALAS 25 August 2014 ___________________________ Assist. Prof. Dr. Zeynep AKTÜRE Supervisor, Department of Architecture, İzmir Institute of Technology ____ ___________________________ ______________________________ Assoc. Prof. Dr. Şeniz ÇIKIŞ Prof. Dr. R. Tuğrul SENGER Head of the Department of Architecture Dean of the Graduate School of Engineering and Sciences ACKNOWLEDGMENTS First and foremost, I would like to thank my supervisor Assist.Prof.Dr.Zeynep AKTÜRE for her guidance, patience and sharing her knowledge during the entire study. This thesis could not be completed without her valuable and unique support. I would like to express my sincere thanks to my committee members Assist. Prof. Dr. Ela ÇİL SAPSAĞLAM, Dr. Çiğdem ALAS, Assoc. Prof. Dr. Erdem ERTEN and Assist. Prof. Dr. Zoltan SOMHEGYI for their invaluable comments and recommendations. I owe thanks to my sisters Yelin DEMİR, Merve KILIÇ, Nil Nadire GELİŞKAN and Banu Işıl IŞIK for not leaving me alone and encouraging me all the time. And I also thank to Seçkin YILDIRIMDEMİR who has unabled to sleep for days to help and motivate me in the hardest times of this study. -

The Fener Greek Patriarchate

PERCEPTIONS JOURNAL OF INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS March - May 1998 Volume III - Number 1 THE FENER GREEK PATRIARCHATE A. SUAT BİLGE Dr. A. Suat Bilge is Professor of International Relations and Ambassador (retired). A controversy concerning the Fener Greek Patriarchate started in Turkey in 1997. It was stated that the Patriarchate could be used both for and against the interests of Turkey. On the one hand, it was claimed that the Patriarchate had intentions to establish itself as an ecumenical church and become a state like the Vatican; that the Orthodox world was trying to gain power in Turkey. On the other hand, some people stated that Turkey could benefit from the prestigious position of the Patriarchate and suggested an improvement in its status. First of all, I want to stress that the Patriarchate no longer enjoys the importance it once possessed in Greek-Turkish relations. Today, the Patriarchate is trying to become influential in Turkish-American relations. The Fener Greek Patriarchate is a historical religious institution. After the division of the Roman Empire, it became the church of the Byzantine Empire and obtained the status of an ecumenical church. With the collapse of the Byzantine Empire, the Patriarchate became the church of the Greeks living within the Ottoman Empire. Besides its functions as a religious institution, the Patriarchate was also granted the right to act as a ministry of Greek affairs by Mehmet II. He granted increased authority and privileges to the Patriarch. After the collapse of the Ottoman Empire, the Fener Greek Patriarchate became the church of the Greeks living within the Republic of Turkey.