Operation Chastise

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

As the Upkeep Bomb Was Not Only a Different Shape to Contemporary

CARRYING UPKEEP As the Upkeep bomb was not only a different shape to contemporary bombs but also had to be spun before release, Barnes Wallis and Vickers-Armstrongs had to come up with a purpose built mounting to be fitted to the Type 464 Lancasters. This section was the most significant and important of all the Type 464 modifications, yet due to its position, in shadow under the black painted belly of the Lancaster, it has never clearly been illustrated before. 14 15 starboard front port rear the calliper arms The four calliper arms were made of cast aluminium with the connecting piece at the apex made of machined steel. Each apex piece contained a circular hub upon which the Upkeep would be suspended. The four arms were attached to the fuselage by heavy duty brackets which allowed the arms to rotate freely outwards to allow a clean release of the bomb. To load the Upkeep, the arms were closed onto it and retained in that position by means of a heavy-duty cable in an inverted ‘Y’ shaped form, with each of the V shaped lengths being connected to one of the front calliper arms, while the stem was attached to a standard 4000lb ‘Type F’ bomb release unit. After the arms were closed, the threaded ends of the cables were fitted through eyelets in the front calliper arms, and retained in position by large bolts, which also allowed for some adjustment and tensioning. 16 17 port front starboard spinning the Upkeep To enable the Upkeep to be spun, A Vickers Variable Speed Gear (VSG) unit was installed forward of the calliper arms and securely bolted to the roof of the bomb bay. -

Crew Members: AJ-F (For Freddie)

April 2019 Issue 01 VM1904C This is the first time we have had such a fantastic selection of signed Dambuster covers. I have included each crew member, even though some may not have signed. I am sure many of you will not be able to resist!! On the night of 16-17 May 1943, Wing Commander Guy Gibson led 617 Squadron, later called the Dambusters, of the Royal Air Force on a bombing raid to destroy three dams in the Ruhr valley, the industrial heartland of Germany. The mission was codenamed Operation ‘Chastise’. The dams were fiercely protected. Torpedo nets in the water stopped underwater attacks and anti-aircraft guns defended them against enemy bombers. But 617 Squadron had a secret weapon: the ‘bouncing bomb’, which was developed by Barnes Wallis. The surviving aircrew of 617 Squadron were lauded as heroes, and Guy Gibson was awarded the Victoria Cross for his actions during the raid. The raid also established 617 Squadron as a specialist precision bombing unit, experimenting with new bomb sights, target marking techniques and colossal new ‘earthquake’ bombs developed by Barnes Wallis. AJ-F (for Freddie) RYD617FN £75 Our choice of Crew Members: cover, signed by Dudley P Heal. F/Sgt Kenneth Brown CGM (Pilot), Sgt Harold B Feneron (Engineer), Sgt Dudley P Heal DFM (Navigator), Sgt H J Hewstone (Wireless Operator), Sgt S Oancia (Bomb Aimer), Sgt D Allaston (Front Gunner), F/Sgt Grant S MacDonald (Rear Gunner). RYD617FR £100 Our choice of cover signed by F/Sgt Grant S MacDonald. £50 per month over 2 months RYD617FRB £100 £50 per month over 2 months RYD617FRA £100 2007 Operation 2007 Formation of 617 Squadron. -

Inscribed 6 (2).Pdf

Inscribed6 CONTENTS 1 1. AVIATION 33 2. MILITARY 59 3. NAVAL 67 4. ROYALTY, POLITICIANS, AND OTHER PUBLIC FIGURES 180 5. SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY 195 6. HIGH LATITUDES, INCLUDING THE POLES 206 7. MOUNTAINEERING 211 8. SPACE EXPLORATION 214 9. GENERAL TRAVEL SECTION 1. AVIATION including books from the libraries of Douglas Bader and “Laddie” Lucas. 1. [AITKEN (Group Captain Sir Max)]. LARIOS (Captain José, Duke of Lerma). Combat over Spain. Memoirs of a Nationalist Fighter Pilot 1936–1939. Portrait frontispiece, illustrations. First edition. 8vo., cloth, pictorial dust jacket. London, Neville Spearman. nd (1966). £80 A presentation copy, inscribed on the half title page ‘To Group Captain Sir Max AitkenDFC. DSO. Let us pray that the high ideals we fought for, with such fervent enthusiasm and sacrifice, may never be allowed to perish or be forgotten. With my warmest regards. Pepito Lerma. May 1968’. From the dust jacket: ‘“Combat over Spain” is one of the few first-hand accounts of the Spanish Civil War, and is the only one published in England to be written from the Nationalist point of view’. Lerma was a bomber and fighter pilot for the duration of the war, flying 278 missions. Aitken, the son of Lord Beaverbrook, joined the RAFVR in 1935, and flew Blenheims and Hurricanes, shooting down 14 enemy aircraft. Dust jacket just creased at the head and tail of the spine. A formidable Vic formation – Bader, Deere, Malan. 2. [BADER (Group Captain Douglas)]. DEERE (Group Captain Alan C.) DOWDING Air Chief Marshal, Lord), foreword. Nine Lives. Portrait frontispiece, illustrations. First edition. -

3.1 the Dambusters Revisited

The Dambusters Revisited J.L. HINKS, Halcrow Group Ltd. C. HEITEFUSS, Ruhr River Association M. CHRIMES, Institution of Civil Engineers SYNOPSIS. The British raid on the Möhne, Eder and Sorpe dams on the night of 16/17 May, 1943 caused the breaching of the 40m high Möhne and 48m high Eder dams and serious damage to the 69m high Sorpe dam. This paper considers the planning for the raid, model testing, the raid itself, the effects of the breaches and the subsequent rehabilitation of the dams. Whilst the subject is of considerable historical interest it also has significant contemporary relevance. Events following the breaching of the dams have been used for the calibration of dambreak studies and emphasise the vulnerability of road and railway bridges which is not always acknowledged in contemporary studies. INTRODUCTION In researching this paper the authors have been very struck by the human interest in the story of English, German and Ukrainian people, whether civilian or in uniform, who participated in some aspect of the raid or who lost their lives or homes. As befits a paper for the British Dam Society, this paper, however, concentrates on the technical questions that arise, leaving the human story to others. This paper was prompted by the BDS sponsored visit, in April 2009, to the Derwent Reservoir by 43 members of the Association of Friends of the Hubert-Engels Institute of Hydraulic Engineering and Applied Hydromechanics at Dresden University of Technology. There is a small museum at the dam run by Vic Hallam, an employee of Severn Trent Water. -

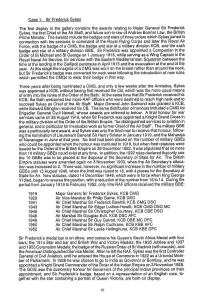

Case 1: Sir Frederick Sykes the First Display in the Gallery Contains

Case 1: Sir Frederick Sykes The first display in the gallery contains the awards relating to Major General Sir Frederick Sykes, the first Chief of the Air Staff, and future son-in-law of Andrew Bonnar Law, the British Prime Minister. The awards include the badges and stars of three orders which Sykes joined in connection with his services in command of the Royal Flying Corps and later the Royal Air Force, with the badge of a CMG, the badge and star of a military division KCB, and the sash badge and star of a military division GBE. Sir Frederick was appointed a Companion in the Order of St Michael and St George on 1 January 1916, while serving as a Wing Captain in the Royal Naval Air Service, for services with the Eastern Mediterranean Squadron between the time of the landing in the Gallipoli peninsula in April 1915 and the evacuation at the end of the year. At this stage the insignia of a CMG was worn on the breast rather than around the neck, but Sir Frederick’s badge was converted for neck wear following the introduction of new rules which permitted the CMGs to wear their badge in that way. Three years after being nominated a CMG, and only a few weeks after the Armistice, Sykes was appointed a KCB, without having first received the CB, which was the more usual means of entry into the ranks of the Order of the Bath. At the same time that Sir Frederick received his KCB, the Bath welcomed two more RAF officers who were destined to reach high rank and to succeed Sykes as Chief of the Air Staff: Major General John Salmond was granted a KCB, while Edward Ellington received his CB. -

Cat No Ref Title Author 3170 H3 an Airman's

Cat Ref Title Author OS Sqdn and other info No 3170 H3 An Airman's Outing "Contact" 1842 B2 History of 607 Sqn R Aux AF, County of 607 Sqn Association 607 RAAF 2898 B4 AAF (Army Air Forces) The Official Guide AAF 1465 G2 British Airship at War 1914-1918 (The) Abbott, P 2504 G2 British Airship at War 1914-1918 (The) Abbott, P 790 B3 Post War Yorkshire Airfields Abraham, Barry 2654 C3 On the Edge of Flight - Development and Absolon, E W Engineering of Aircraft 3307 H1 Looking Up At The Sky. 50 years flying with Adcock, Sid the RAF 1592 F1 Burning Blue: A New History of the Battle of Addison, P/Craig JA Britain (The) 942 F5 History of the German Night Fighter Force Aders, Gerbhard 1917-1945 2392 B1 From the Ground Up Adkin, F 462 A3 Republic P-47 Thunderbolt Aero Publishers' Staff 961 A1 Pictorial Review Aeroplane 1190 J5 Aeroplane 1993 Aeroplane 1191 J5 Aeroplane 1998 Aeroplane 1192 J5 Aeroplane 1992 Aeroplane 1193 J5 Aeroplane 1997 Aeroplane 1194 J5 Aeroplane 1994 Aeroplane 1195 J5 Aeroplane 1990 Aeroplane Cat Ref Title Author OS Sqdn and other info No 1196 J5 Aeroplane 1994 Aeroplane 1197 J5 Aeroplane 1989 Aeroplane 1198 J5 Aeroplane 1991 Aeroplane 1200 J5 Aeroplane 1995 Aeroplane 1201 J5 Aeroplane 1996 Aeroplane 1525 J5 Aeroplane 1974 Aeroplane (Pub.) 1526 J5 Aeroplane 1975 Aeroplane (Pub.) 1527 J5 Aeroplane 1976 Aeroplane (Pub.) 1528 J5 Aeroplane 1977 Aeroplane (Pub.) 1529 J5 Aeroplane 1978 Aeroplane (Pub.) 1530 J5 Aeroplane 1979 Aeroplane (Pub.) 1531 J5 Aeroplane 1980 Aeroplane (Pub.) 1532 J5 Aeroplane 1981 Aeroplane (Pub.) 1533 J5 -

![Guide to the MS-196: “Meine Fahrten 1925-1938” Scrapbook [My Trips 1925-1938]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6096/guide-to-the-ms-196-meine-fahrten-1925-1938-scrapbook-my-trips-1925-1938-296096.webp)

Guide to the MS-196: “Meine Fahrten 1925-1938” Scrapbook [My Trips 1925-1938]

________________________________________________________________________ Guide to the MS-196: “Meine Fahrten 1925-1938” Scrapbook [My Trips 1925-1938] Jesse Siegel ’16, Smith Project Intern July 2016 MS – 196: “Meine Fahrten” Scrapbook (Title page, 36 pages) Inclusive Dates: October 1925—April 1938 Bulk Dates: 1927, 1929-1932 Processed by: Jesse Siegel ’16, Smith Project Intern July 15, 2016 Provenance Purchased from Between the Covers Company, 2014. Biographical Note Possibly a group of three brothers—G. Leiber, V. Erich Leiber, and R. Leiber— participated in the German youth movement during the 1920s and 1930s. The probable maker of the photo album, Erich Leiber, was probably born before 1915 in north- western Germany, most likely in the federal state of North Rhine-Westphalia. His early experiences with the youth movement appear to have been in conjunction with school outings and Christian Union for Young Men (CVJM) in Austria. He also travelled to Sweden in 1928, but most of his travels are concentrated in northwestern Germany. Later in 1931 he became an active member in a conservative organization, possibly the Deutsche Pfadfinderschaft St. Georg,1 participating in outings to nationalistic locations such as the Hermann Monument in the Teutoburg Forest and to the Naval Academy at Mürwik in Kiel. In 1933 Erich Leiber joined the SA and became a youth leader or liaison for a Hitler Youth unit while still maintaining a connection to a group called Team Yorck, a probable extension of prior youth movement associates. After 1935 Erich’s travels seem reduced to a small group of male friends, ending with an Easter trip along the Rhine River in 1938. -

Extracts From…

Extracts from…. The Dambusters & the T1154/R1155 The VMARS News Sheet Issue 122 May 2013 During operations over enemy territory, wireless communications between Bomber Command aircraft and their operations rooms were strictly limited, with total wireless silence being enforced at least until the target area had been reached to avoid alerting the enemy. Between aircraft flying in defensive formations en-route to the target, the normal practice was to signal using Aldis lamps for sharing navigational and other essential operational information, although even this basic method of communication was kept to a minimum. Because the dam attacks required close co-ordination of aircraft operating sequentially over the target area, 617 Squadron’s Lancasters were fitted with VHF sets in order to provide Gibson with effective command and control of the Squadron during the attack. These wireless sets are believed to have been the TR1143 VHF units fitted to most RAF fighters at that time, but not normally to heavy bombers. They were crystal controlled four channel sets operating at 10 W between 100 Mc/s and 120 Mc/s. Using T1154 transmitters on an HF link and to keep HF wireless transmissions brief, a series of code words were pre-arranged for sending initial target damage assessments the several hundred miles back to the Squadron’s operations room located in Grantham, 30 miles south of their Scampton airfield base. There was an extensive list of codes available for the reports. For example, the code “Goner 58A” was designated “weapon released at Mohne VMARS Committee Member Pete Shepherd G7DXV, with the Dam, exploded 50 yards from dam with no breach made”. -

Imperial Airways

IMPERIAL AIRWAYS 1 ARMSTRONG WHITWORTH. AW.XV Atlanta, G-ABPI, Imperial Airways. Photograph, 9 x 14 cm. 6,00 2 ARMSTRONG WHITWORTH. G-ADSR, Ensign Imperial Airways, air to air. Photograph, 9 x 14 cm. 6,00 3 ARMSTRONG WHITWORTH. AW15 Atlanta, G-ABPI, Imperial Airways, air to air, 1932. Photograph, 9 x 14 cm. 6,00 4 ARMSTRONG WHITWORTH. Argosy I, G-EBLF, Imperial Airways, 1929. Photograph, 9 x 14 cm. 6,00 5 ARMSTRONG WHITWORTH. Ensign, G-ADSR, Imperial Airways, 1937. Photograph, 9 x 14 cm. 6,00 6 ARMSTRONG WHITWORTH. Atlanta, G-ABTL, Astraea Imperial Airways, Royal Mail GR. Photograph, 9 x 14 cm. 6,00 7 ARMSTRONG WHITWORTH. Atalanta, G-ABTK, Athena, Imperial Airways. Photograph, 9 x 14 cm. 6,00 8 ARMSTRONG WHITWORTH. AW Argosy, G-EBLO, Imperial Airways. Photograph, 9 x 14 cm. 6,00 9 ARMSTRONG WHITWORTH. AW Ensign, G-ADSR, Imperial Airways, air to air. Photograph, 9 x 14 cm. 6,00 10 ARMSTRONG WHITWORTH. Ensign, G-ADSR, Imperial Airways, air to air. Photograph, 9 x 14 cm. 6,00 11 ARMSTRONG WHITWORTH. Argosy I, G-EBOZ, Imperial Airways. Photograph, 9 x 14 cm. 6,00 12 ARMSTRONG WHITWORTH. AW 27 Ensign, G-ADSR, Imperial Airways, air to air. Photograph, 9 x 14 cm. 6,00 13 AVRO. 652, G-ACRM, Imperial Airways. Photograph, 9 x 14 cm. 6,00 14 AVRO. 652, G-ACRN, Imperial Airways. Photograph, 9 x 14 cm. 6,00 15 AVRO. Avalon, G-ACRN, Imperial Airways. Photograph, 9 x 14 cm. 6,00 16 BENNETT, D. C. -

Canadian Airmen Lost in Wwii by Date 1943

CANADA'S AIR WAR 1945 updated 21/04/08 January 1945 424 Sqn. and 433 Sqn. begin to re-equip with Lancaster B.I & B.III aircraft (RCAF Sqns.). 443 Sqn. begins to re-equip with Spitfire XIV and XIVe aircraft (RCAF Sqns.). Helicopter Training School established in England on Sikorsky Hoverfly I helicopters. One of these aircraft is transferred to the RCAF. An additional 16 PLUTO fuel pipelines are laid under the English Channel to points in France (Oxford). Japanese airstrip at Sandakan, Borneo, is put out of action by Allied bombing. Built with forced labour by some 3,600 Indonesian civilians and 2,400 Australian and British PoWs captured at Singapore (of which only some 1,900 were still alive at this time). It is decided to abandon the airfield. Between January and March the prisoners are force marched in groups to a new location 160 miles away, but most cannot complete the journey due to disease and malnutrition, and are killed by their guards. Only 6 Australian servicemen are found alive from this group at the end of the war, having escaped from the column, and only 3 of these survived to testify against their guards. All the remaining enlisted RAF prisoners of 205 Sqn., captured at Singapore and Indonesia, died in these death marches (Jardine, wikipedia). On the Russian front Soviet and Allied air forces (French, Czechoslovakian, Polish, etc, units flying under Soviet command) on their front with Germany total over 16,000 fighters, bombers, dive bombers and ground attack aircraft (Passingham & Klepacki). During January #2 Flying Instructor School, Pearce, Alberta, closes (http://www.bombercrew.com/BCATP.htm). -

US Army Air Forces.Pdf

U.S. Army Military History Institute Air-WWII 950 Soldiers Drive Carlisle Barracks, PA 17013-5021 11 Aug 2012 U.S. ARMY AIR FORCES, WWII A Working Bibliography of MHI Sources CONTENTS General Sources......p.1 Organization/Administration/Training/Equipment......p.3 Bombing Technique.....p.4 Aircraft.....p.4 Overseas Operations/Units General Sources......p.6 Europe.......p.7 -Air Attacks on Ploesti…..p.10 -Firebombing of Dresden…..p.11 -Accidental Bombing of Switzerland…..p.13 Mediterranean.....p.13 -Lady-Be-Good…..p.14 Asia-Pacific.....p.14 The “Confederate” Air Force…..p.16 GENERAL SOURCES Air Force/AAF Review, 1942-46. Per. Official service journal. Arnold, Henry H. "The Army Air Forces." Army Navy Journal (22 Aug 1942): pp. 1441-42. Per. Bowman, Martin W. Clash of Eagles: USAAF 8th Air Force Bombers Versus the Luftwaffe in World War 2. South Yorkshire, England: Pen & Sword Aviation, 2006. 254 p. D785.B6962. Bright, Charles D., editor. Historical Dictionary of the U.S. Air Force. NY: Greenwood, 1992. 710 p. UH23.3.H36. Eaker, Ira. Oral history transcripts & clippings. Arch. Ehlers, Robert S., Jr. Targeting the Third Reich: Air Intelligence and the Allied Bombing Campaigns. Lawrence, KS: UP of KS, 2009. 422 p. D810.S7.E45. U.S. Army Air Forces, WWII p.2 Jablonski, Edward. America in the Air War. Alexandria, VA: Time-Life, 1982. 176 p. D790.J33. Merry, Lois K. Women Military Pilots of World War II: A History with Biographies of American, British, Russian and German Aviators. Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2011. 212 p. D785.M47. Mireles, Anthony J Fatal Army Air Forces Aviation Accidents in the United States, 1941-1945. -

Publisher's Note

Adam Matthew Publications is an imprint of Adam Matthew Digital Ltd, Pelham House, London Road, Marlborough, Wiltshire, SN8 2AG, ENGLAND Telephone: +44 (1672) 511921 Fax: +44 (1672) 511663 Email: [email protected] POPULAR NEWSPAPERS DURING WORLD WAR II Parts 1 to 5: 1939-1945 (The Daily Express, The Mirror, The News of The World, The People and The Sunday Express) Publisher's Note This microfilm publication makes available complete runs the Daily Express, The Daily Mirror, the News of the World, The People, and the Sunday Express for the years 1939 through to 1945. The project is organised in five parts and covers the newspapers in chronological sequence. Part 1 provides full coverage for 1939; Part 2: 1940; Part 3: 1941; Part 4: 1942-1943; and finally, Part 5 covers 1944-1945. At last social historians and students of journalism can consult complete war-time runs of Britain’s popular newspapers in their libraries. Less august than the papers of record, it is these papers which reveal most about the impact of the war on the home front, the way in which people amused themselves in the face of adversity, and the way in which public morale was kept high through a mixture of propaganda and judicious reporting. Most importantly, it is through these papers that we can see how most ordinary people received news of the war. For, with a combined circulation of over 23 million by 1948, and a secondary readership far in excess of these figures, the News of the World, The People, the Daily Express, The Daily Mirror, and the Sunday Express reached into the homes of the majority of the British public and played a critical role in shaping public perceptions of the war.