Felix Mendelssohn Violin Concerto No

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Genre Album Artist and Title Avantgarde Various - Linn SACD Sampler Various - Stay in Tune with Pentatone

Genre Album Artist and Title Avantgarde Various - Linn SACD Sampler Various - Stay in Tune with PentaTone Bluegrass Nickel Creek - This Side Nickel Creek - Nickel Creek Christmas Bach Collegium Japan - Verbum caro factum est Choir of St John's College, Cambridge/Challenger/Nethsingha - On Christmas Night Elena Fink, Le Quatuor Romantique - A Late Romantic Christmas Eve Le Quatuor Romantique - A Late Romantic Christmas Eve Oscar's Motet Choir - Cantate Domino Stile Antico - Puer natus est: Music for Advent and Christmas - Stile Antico Vox Aurea, Sanna Salminen - Matkalla jouluun / A Journey into Christmas Classical Aachen Symphony, Vocapella Choir - Verdi Missa da Requiem Academy of St Martin in the Fields, Marriner - Mozart: Clarinet Concert in A, KV 622 , Clarinet Quintet in A, KV 581 Academy of St Martin in the Fields, Marriner - The Art of the Fugue Angela Hewitt, ACO - Bach Keyboard Concertos Vol 2 Angela Hewitt, ACO - Bach Keyboard Concertos Vol1 Angela Hewitt, piano - J.-P Rameau: Suites Artur Pizarro - Chopin Piano Sonatas Artur Pizarro - Frederic Chopin Artur Pizarro, Scottish Chamber Orchestra - Beethoven Piano Concerto No.5 Artur Pizarro, Scottish Chamber Orchestra - Beethoven Piano Concertos No.3 & No.4 Atlanta Symphony Orchestra - Vaughan Williams: A Sea Symphony Brendel, SCO, Mackerras - Mozart: Piano Concertos K271 & K503 Cincinnati Pops Orchestra, Kunzel - A Celtic Spectacular Cincinnati Pops Orchestra, Kunzel - Tchaikovsky 1812 Donald Runnicles, Atlanta Symphony Orchestra and Chorus - Orff: Carmina Burana Dunedin Consort -

The Authenticity of Genius Transcript

The Authenticity of Genius Transcript Date: Tuesday, 15 February 2011 - 1:00PM Location: Museum of London Gresham Lecture, 15 February 2011 The Authenticity of Genius Professor Christopher Hogwood You see that I have arrived with eight accomplices today, all named on the programme sheet. I shall just tell you how we arrived at this and the purpose. As you know, the overriding theme of these six lectures, this year has been the theme of authenticity. We have done various aspects such as whether the piece in question is what it says on the tin and that sort of thing. Last time, there were many fakes. The next lecture was going to be taking the story of music, as it were, from the manuscript, or from the library stage, into the sort of thing you can pick off the shelf and buy – i.e. the work of the musicologist, the librarian and the historian. The final lecture will carry that story on - dealing with the business of picking the printed volume off the shelf and deciding to include it in a recital, in a concert, in a recording, and for that, I will be joined by Dame Emma Kirby. We will talk about what goes on in a performer’s life and in a performer’s mind when faced with a new piece of repertoire and how you bring it to life respectably from the silent piece of music that you took from the library or bought off the shelf. That does seem to leave one stage missing - the stage before the thing hits the paper, which is what goes on to create this music, and that is why we have “Authenticity of Genius” today. -

23 a 30 De Março Programa

SEMANA DO PIANO 23 a 30 de março programa 23 e 24 de março Masterclasse Luís Pipa Local: Conservatório de Música Calouste Gulbenkian de Braga A S e m a n a d o Pi a n o é u m a at i v i d a d e Os Concertos com Artur Pizarro e Pedro 25 e 26 de março desenvolvida numa parceria entre a Câmara Burmester trazem à cidade de Braga duas das Concurso Regional de Piano Local: Conservatório de Música Calouste Gulbenkian de Braga Municipal de Braga (CMB), pelouro da cultura, e maiores referências do piano em Portugal. O * 25 março | 21.30 horas o Conservatório de Música Calouste Gulbenkian concerto do Bruno Ferreira é o encontro Concerto Piano, Artur Pizarro de Braga (CMCGB), cujo objetivo é celebrar e marcado com um jovem talento, que foi prémio Local: Auditório Vita. Obras de: Chopin, Schumann; José Vianna da Motta, colocar o Piano no centro da atenção da cidade Conservatório na sua edição de 2014/15. Luís Costa e Claudio Carneyro. num convite à fruição de momentos excelentes A componente pedagógica, desta atividade, Entrada: 5 euros. para todos. convida os alunos de Música a usufruírem da 27 de março | 19 horas À volta do Piano Day, dia celebrado em todo o master classe do prof. Luís Pipa, que decorre Concerto Jovem talento- Piano, Bruno Ferreira prémio Conservatório ed. 2014-15. mundo ao 88º dia do ano, coincidindo com as 88 nos dois primeiros dias da semana do piano, e a Local: Conservatório de Música Calouste Gulbenkian de Braga Obras: R. -

November 8, 2020 Twenty-Third Sunday After Pentecost Proper 27 Website: Stpaulsokc.Org

November 8, 2020 Twenty-third Sunday after Pentecost Proper 27 Website: stpaulsokc.org Prelude Wachet auf! ruft uns die Stimme 2. Zion hears the watchman singing; (Sleepers, wake! a voice astounds us) her heart with joyful hope is springing, J.S. Bach she wakes and hurries through the night. Forth he comes, her Bridegroom glorious Welcome in strength of grace, in truth victorious: Welcome to St. Paul’s Episcopal Cathedral; we are her star is risen, her light grows bright. so glad you are here. St. Paul’s is a safe and welcom- Now come, most worthy Lord, ing place for all people. If you are new to St. Paul’s God’s Son, Incarnate Word, we encourage you to get connected with our weekly Alleluia! email newsletter. You can sign up online at We follow all and heed your call stpaulsokc.org. to come into the banquet hall. A friendly reminder to those who are worshiping in- 3. Lamb of God, the heavens adore you; person, please have your mask on (covering your let saints and angels sing before you, mouth and nose) and maintain social distancing at as harps and cymbals swell the sound. all times during the service. Additionally, we cannot Twelve great pearls, the city’s portals: have congregational singing at this time, so during through them we stream to join the immortals the hymns we invite you to listen to the choristers and as we with joy your throne surround. follow along with the words printed in the bulletin. No eye has known the sight, We thank you in advance for adhering to these Dioc- no ear heard such delight: esan protocols which keep us all safe and allow for us Alleluia! to worship in-person. -

The Seventh Season Being Mendelssohn CHAMBER MUSIC FESTIVAL and INSTITUTE July 17–August 8, 2009 David Finckel and Wu Han, Artistic Directors

The Seventh Season Being Mendelssohn CHAMBER MUSIC FESTIVAL AND INSTITUTE July 17–August 8, 2009 David Finckel and Wu Han, Artistic Directors Music@Menlo Being Mendelssohn the seventh season july 17–august 8, 2009 david finckel and wu han, artistic directors Contents 3 A Message from the Artistic Directors 5 Welcome from the Executive Director 7 Being Mendelssohn: Program Information 8 Essay: “Mendelssohn and Us” by R. Larry Todd 10 Encounters I–IV 12 Concert Programs I–V 29 Mendelssohn String Quartet Cycle I–III 35 Carte Blanche Concerts I–III 46 Chamber Music Institute 48 Prelude Performances 54 Koret Young Performers Concerts 57 Open House 58 Café Conversations 59 Master Classes 60 Visual Arts and the Festival 61 Artist and Faculty Biographies 74 Glossary 76 Join Music@Menlo 80 Acknowledgments 81 Ticket and Performance Information 83 Music@Menlo LIVE 84 Festival Calendar Cover artwork: untitled, 2009, oil on card stock, 40 x 40 cm by Theo Noll. Inside (p. 60): paintings by Theo Noll. Images on pp. 1, 7, 9 (Mendelssohn portrait), 10 (Mendelssohn portrait), 12, 16, 19, 23, and 26 courtesy of Bildarchiv Preussischer Kulturbesitz/Art Resource, NY. Images on pp. 10–11 (landscape) courtesy of Lebrecht Music and Arts; (insects, Mendelssohn on deathbed) courtesy of the Bridgeman Art Library. Photographs on pp. 30–31, Pacifica Quartet, courtesy of the Chamber Music Society of Lincoln Center. Theo Noll (p. 60): Simone Geissler. Bruce Adolphe (p. 61), Orli Shaham (p. 66), Da-Hong Seetoo (p. 83): Christian Steiner. William Bennett (p. 62): Ralph Granich. Hasse Borup (p. 62): Mary Noble Ours. -

Download Programme

Programme Mozart: Die Zauberflöte Overture (The Magic Flute) Beethoven: Piano Concerto No. 4 in G major -- Interval -- Brahms: Symphony No. 2 in D major Soloists Aya Kawabata was born in Tokyo. From 1989 to 1991 she lived in England and studied at the Junior Guildhall School of Music with Joan Havill. In 1997 she was offered a place at the Tokyo Metropolitan High School of Music and Arts to study for three years during which time she studied with Professor Teruji Karashima and was awarded a silver medal in the Japan Classical Competition. In 2001 she came back to England to study at the Royal Academy of Music and completed a Bachelor of Music degree with First Class Honours in 2005. She studied with Ian Fountain and Diana Ketler, and was invited to play in master classes with Alexander Satz, Petras Geniusas and Emanuel Krasovsky. During her time at the Academy, she was awarded the Blakiston Prize (Highly Commended), the Mathew Philimore Prize (Winner), the George Award (Winner), the Leslie England Prize (Very Highly Commended), the Wilfred Parry Prize (Very Highly Commended), the Maud Hornsby Award (Winner), and the Peter Latham Gift (Winner) for her performances, and also was awarded a bursary award for her studies. She has taken master classes with Armen Babakhanian, Andrew Ball, Christopher Elton, Ruth Harte, John Lill, Artur Pizarro, and Veronika Vitaitė in various festivals, and has performed extensively in England – London (including performances as a soloist with orchestras), Cambridge, Leeds, Salisbury, and Bristol – and also in Scotland, Austria, France, Italy, Lithuania, Latvia, Kazakhstan (broadcast live on Kazakh TV and satellite), Turkey (filming for NHK), and Japan. -

Naxcat2005 ABRIDGED VERSION

CONTENTS Foreword by Klaus Heymann . 4 Alphabetical List of Works by Composer . 6 Collections . 88 Alphorn 88 Easy Listening 102 Operetta 114 American Classics 88 Flute 106 Orchestral 114 American Jewish Music 88 Funeral Music 106 Organ 117 Ballet 88 Glass Harmonica 106 Piano 118 Baroque 88 Guitar 106 Russian 120 Bassoon 90 Gypsy 109 Samplers 120 Best Of series 90 Harp 109 Saxophone 121 British Music 92 Harpsichord 109 Trombone 121 Cello 92 Horn 109 Tr umpet 121 Chamber Music 93 Light Classics 109 Viennese 122 Chill With 93 Lute 110 Violin 122 Christmas 94 Music for Meditation 110 Vocal and Choral 123 Cinema Classics 96 Oboe 111 Wedding 125 Clarinet 99 Ondes Martenot 111 White Box 125 Early Music 100 Operatic 111 Wind 126 Naxos Jazz . 126 Naxos World . 127 Naxos Educational . 127 Naxos Super Audio CD . 128 Naxos DVD Audio . 129 Naxos DVD . 129 List of Naxos Distributors . 130 Naxos Website: www.naxos.com NaxCat2005 ABRIDGED VERSION2 23/12/2004, 11:54am Symbols used in this catalogue # New release not listed in 2004 Catalogue $ Recording scheduled to be released before 31 March, 2005 † Please note that not all titles are available in all territories. Check with your local distributor for availability. 2 Also available on Mini-Disc (MD)(7.XXXXXX) Reviews and Ratings Over the years, Naxos recordings have received outstanding critical acclaim in virtually every specialized and general-interest publication around the world. In this catalogue we are only listing ratings which summarize a more detailed review in a single number or a single rating. Our recordings receive favourable reviews in many other publications which, however, do not use a simple, easy to understand rating system. -

Musmeds&Notes-October 21, 2020

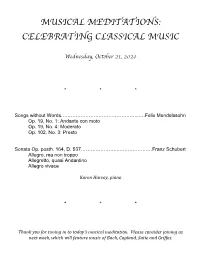

MUSICAL MEDITATIONS: CELEBRATING CLASSICAL MUSIC Wednesday, October 21, 2020 * * * Songs without Words………………………………………...….Felix Mendelssohn Op. 19, No. 1: Andante con moto Op. 19, No. 4: Moderato Op. 102, No. 3: Presto Sonata Op. posth. 164, D. 537…………………..…………………Franz Schubert Allegro, ma non troppo Allegretto, quasi Andantino Allegro vivace Karen Harvey, piano * * * Thank you for tuning in to today’s musical meditation. Please consider joining us next week, which will feature music of Bach, Copland, Satie and Griffes. Notes on today’s music Jakob Ludwig Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy (February 3, 1809 – November 4, 1847), a.k.a. Felix Mendelssohn, was a German composer, pianist, organist and conductor of the early Romantic period. Mendelssohn's compositions incluDe symphonies, concertos, piano music, organ music and chamber music. His best-known works incluDe the overture and incidental music for A Midsummer Night's Dream (containing the famous Wedding March), the Italian Symphony, the Scottish Symphony, the oratorio St. Paul, the oratorio Elijah, the overture The Hebrides, the mature Violin Concerto and the String Octet. The meloDy for the Christmas carol "Hark! The HeralD Angels Sing" is also his. Songs Without Words are his most famous solo piano compositions. A grandson of the philosopher Moses MenDelssohn, Felix MenDelssohn was born into a prominent Jewish family, anD though he was recogniseD early as a musical proDigy, his parents were cautious and did not seek to capitalise on his talent. MenDelssohn enjoyeD early success in Germany, anD singlehandedly reviveD interest in the music of Johann Sebastian Bach with his performance of the St. Matthew Passion in 1829. -

Julian Pellicano Repertoire Copy

JULIAN PELLICANO Resident Conductor Winnipeg Symphony Orchestra CONCERT REPERTOIRE John Adams Scratchband Shaker Loops The Wound Dresser Timo Andres Home Strech George Antheil Ballet Mecanique (ed. 1923) Ballet Mecanique (ed. 1957) J. S. Bach Little Fugue in G minor (arr. Stokowski) Orchestral Suite no. 1 in C major, BWV 1066 Orchestral Suite no. 2 in B minor, BWV 1067 Orchestral Suite no. 3 in D major, BWV 1068 Ricercar a 6 from Musical Offering (orch. Webern) Samuel Barber Adagio for Strings A Hand of Bridge Canzonetta Knoxville: Summer of 1915 Second Essay, op. 17 Bela Bartok Concerto for Orchestra Divertimento Romanian Folk Dances Viola Concerto Ludwig van Beethoven Egmont Overture, op. 84 Fidelo Overture, op. 72 Leonore Overture no. 3, op. 72b Coriolan Overture, op. 62 KIng Stephen Overture, op. 117 Creatures of Prometheus Overture, op. 43 No Non Turbati! Octet, op. 103 Piano Concerti no. 1 - 5 Symphonies no. 1 - 9 Violin Concerto, op. 61 Alban Berg Drei Orchesterstucke, op. 6 Hector Berlioz Roman Carnival Overture Royal Hunt and Storm from Les Troyens Symphonie Fantastique, op. 14 Scene D’Amour from Romeo and Juliet Leonard Bernstein Overture to Candide On the Town: Three Dance Episodes Overture to WEst Side Story (ed. Peress) Symphonic Dances from West Side Story Slava! Georges Bizet Carmen Suite no. 1 Carmen Suite no. 2 L’Arlesienne Suite no. 1 L’Arlesienne Suite no. 2 Alexander Borodin In the Steppes of Central Asia Polovtsian Dances Symphony no. 2 Johannes Brahms Academic Festival Overture, op. 80 Hungarian Dances no. 1,3,5,6,20,21 Symphonies no. -

Mendelssohn Bartholdy

MENDELSSOHN BARTHOLDY Ruy Blas Ouvertüre / Overture Herausgegeben von / Edited by Christopher Hogwood Urtext Partitur / Score Bärenreiter Kassel · Basel · London · New York · Praha BA 9054 INHALT / CONTENTS Preface. III Introduction . IV Vorwort . IX Einführung . X Facsimiles / Faksimiles . XVI Ruy Blas Ouvertüre / Overture Version 1 / Fassung 1 . 1 Version 2 / Fassung 2 . 47 Critical Commentary . 95 ORCHESTRA Flauto I, II, Oboe I, II, Clarinetto I, II, Fagotto I, II; Corno I–IV, Tromba I, II, Trombone I–III; Timpani; Archi Duration / Aufführungsdauer: ca. 7 min. © 2009 by Bärenreiter-Verlag Karl Vötterle GmbH & Co. KG, Kassel Alle Rechte vorbehalten / All rights reserved / Printed in Germany Vervielfältigungen jeglicher Art sind gesetzlich verboten. Any unauthorized reproduction is prohibited by law. ISMN 979-0-006-52290-3 PREFACE “Had Mendelssohn only titled his orchestral works in were popular in their time but set aside by Mendelssohn one movement as ‘symphonic poems’, which Liszt later and published posthumously in less than faithful ver- invented, he would probably be celebrated today as the sions. (e. g. Ruy Blas). Of his revisions, the Overture in C, creator of programme music and would have taken his op. B, received the most drastic enlargement, growing position at the beginning of a new period rather than the from a Nocturno for ? players in F@B to a full Ouvertüre end of an old one. He would then be referred to as the für Harmoniemusik (@ players and percussion) by FAF. ‘first of the moderns’ instead of the ‘last of the classics’ ” In other cases, with the exception of the Ouvertüre zum (Felix Weingartner: Die Sym phonie nach Beethoven, FGF). -

Ingrid Fliter Frédéric Chopin Piano Concertos

Ingrid Fliter Frédéric Chopin Piano Concertos Jun Märkl conductor Scottish Chamber Orchestra Ingrid Fliter Frédéric Chopin Piano Concertos Jun Märkl conductor Scottish Chamber Orchestra Piano Concerto No. 1 in E minor, Opus 11 1. Allegro maestoso 20:02 2. Romanze: Larghetto 9:33 3. Rondo: Vivace 10:11 Piano Concerto No. 2 in F minor, Opus 21 4. Maestoso 15:05 5. Larghetto 9:25 6. Allegro vivace 8:52 Total Time: 73:21 Recorded at Usher Hall, Edinburgh, UK from 7 – 9 June 2013. Produced by John Fraser. Recorded by Philip Hobbs. Assistant engineering by Robert Cammidge. Post-production by Julia Thomas. Design by Red Empire. Colour photographs of Ingrid by Anton Dressler. 2 Chopin: Piano Concertos ‘Hats off, gentlemen, a genius!’ Robert Schumann’s celebrated appraisal of the seventeen-year-old Frédéric Chopin in the Allgemeine musikalische Zeitung of 7 December 1831 thrust the young Polish wunderkind into the European limelight in no uncertain terms. For Schumann, as for many others, the success of the Variations on Là ci darem la mano from Mozart’s Don Giovanni raised considerable expectations for what was to follow, expectations that would, with almost unseemly abruptness, be left unrealised. 3 Composed for piano and orchestra, the Variations had been only the second piece by the teenage prodigy to be published in 1827 (the fi rst, the precocious Rondo in C minor, composed two years earlier when he was just fi fteen, a markedly less ambitious piece for solo piano). It was also Chopin’s fi rst work for a pairing that was to become both touchstone and trial for composers eager to make their mark in the middle of the nineteenth century but one that was soon to lose its allure for Chopin himself. -

Brahms Rhapsodizing: the Alto Rhapsody and Its Expressive Double Author(S): Christopher Reynolds Reviewed Work(S): Source: the Journal of Musicology, Vol

Brahms Rhapsodizing: The Alto Rhapsody and Its Expressive Double Author(s): Christopher Reynolds Reviewed work(s): Source: The Journal of Musicology, Vol. 29, No. 2 (Spring 2012), pp. 191-238 Published by: University of California Press Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1525/jm.2012.29.2.191 . Accessed: 10/07/2012 14:09 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. University of California Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The Journal of Musicology. http://www.jstor.org Brahms Rhapsodizing: The Alto Rhapsody and Its Expressive Double CHristop H er R E Y noL ds For Donald C. Johns Biographers have always recognized the Alto Rhapsody to be one of Brahms’s most personal works; indeed, both the composer and Clara Schumann left several unusually specific com- ments that suggest that this poignant setting of Goethe’s text about a lonely, embittered man had a particular significance for Brahms. Clara 191 wrote in her diary that after her daughter Julie Schumann announced her engagement to an Italian count on 11 July 1869, Brahms suddenly began