Mendelssohn · Escher String Quartet Quartets No

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Authenticity of Genius Transcript

The Authenticity of Genius Transcript Date: Tuesday, 15 February 2011 - 1:00PM Location: Museum of London Gresham Lecture, 15 February 2011 The Authenticity of Genius Professor Christopher Hogwood You see that I have arrived with eight accomplices today, all named on the programme sheet. I shall just tell you how we arrived at this and the purpose. As you know, the overriding theme of these six lectures, this year has been the theme of authenticity. We have done various aspects such as whether the piece in question is what it says on the tin and that sort of thing. Last time, there were many fakes. The next lecture was going to be taking the story of music, as it were, from the manuscript, or from the library stage, into the sort of thing you can pick off the shelf and buy – i.e. the work of the musicologist, the librarian and the historian. The final lecture will carry that story on - dealing with the business of picking the printed volume off the shelf and deciding to include it in a recital, in a concert, in a recording, and for that, I will be joined by Dame Emma Kirby. We will talk about what goes on in a performer’s life and in a performer’s mind when faced with a new piece of repertoire and how you bring it to life respectably from the silent piece of music that you took from the library or bought off the shelf. That does seem to leave one stage missing - the stage before the thing hits the paper, which is what goes on to create this music, and that is why we have “Authenticity of Genius” today. -

Download Booklet

572813 bk Zemlinsky EU_572813 bk Zemlinsky EU 23/05/2013 13:45 Page 4 Escher String Quartet Alexander Adam Barnett-Hart, Violin I • Wu Jie, Violin II • Pierre Lapointe, Viola • Dane Johansen, Cello Championed by the Emerson String Quartet, the Escher String ZEMLINSKY Quartet players were BBC New Generation Artists from 2010- 2012, giving débuts at both the Wigmore Hall and the BBC Proms String Quartets • 1 at Cadogan Hall. In their home town of New York, the quartet recently completed a three-year Escher String Quartet Rising Stars residency at The Chamber Music Society of Lincoln Center. Within months of its inception in 2005, the Escher Quartet was invited by both Pinchas Zukerman and Itzhak Perlman to be Quartet-in-Residence at each artist’s summer festival: the Young Artists Programme at Canada’s National Arts Centre; and the Perlman Chamber Music Program on Shelter Island, NY. Photo: Henry Fair In addition, the quartet has collaborated with artists such as Andrés Diaz, Lawrence Dutton, Kurt Elling, Leon Fleisher, Anja Lechner, Vadim Gluzman, Angela Yoffe, Gary Hoffman, Joseph Kalichstein, Kurt Muroki, Joseph Silverstein, Khatia Buniatishvili, Benjamin Grosvenor and Matthew Hunt, as well pop folk singer-songwriter Luke Temple. Recent performances include appearances at the Cheltenham, Lichfield and City of London Festivals, the Auditorium du Louvre in Paris, 92nd Street Y in New York, the Kennedy Center in Washington DC and the Ravinia and Caramoor festivals. Elsewhere, the quartet undertook a tour of China including Beijing, Shanghai and Hangzhou, and made its Australian début with Brett Dean at the Perth International Arts Festival. -

November 8, 2020 Twenty-Third Sunday After Pentecost Proper 27 Website: Stpaulsokc.Org

November 8, 2020 Twenty-third Sunday after Pentecost Proper 27 Website: stpaulsokc.org Prelude Wachet auf! ruft uns die Stimme 2. Zion hears the watchman singing; (Sleepers, wake! a voice astounds us) her heart with joyful hope is springing, J.S. Bach she wakes and hurries through the night. Forth he comes, her Bridegroom glorious Welcome in strength of grace, in truth victorious: Welcome to St. Paul’s Episcopal Cathedral; we are her star is risen, her light grows bright. so glad you are here. St. Paul’s is a safe and welcom- Now come, most worthy Lord, ing place for all people. If you are new to St. Paul’s God’s Son, Incarnate Word, we encourage you to get connected with our weekly Alleluia! email newsletter. You can sign up online at We follow all and heed your call stpaulsokc.org. to come into the banquet hall. A friendly reminder to those who are worshiping in- 3. Lamb of God, the heavens adore you; person, please have your mask on (covering your let saints and angels sing before you, mouth and nose) and maintain social distancing at as harps and cymbals swell the sound. all times during the service. Additionally, we cannot Twelve great pearls, the city’s portals: have congregational singing at this time, so during through them we stream to join the immortals the hymns we invite you to listen to the choristers and as we with joy your throne surround. follow along with the words printed in the bulletin. No eye has known the sight, We thank you in advance for adhering to these Dioc- no ear heard such delight: esan protocols which keep us all safe and allow for us Alleluia! to worship in-person. -

Escher String Quartet String Quartets: No

MENDELSSOHN · ESCHER STRING QUARTET STRING QUARTETS: NO. 5 IN E FLAT MAJOR & NO. 6 IN F MAJOR Front cover from left: Pierre Lapointe, Adam Barnett-Hart, Aaron Boyd, Dane Johansen BIS-2160 BIS-2160 booklet cover.indd 1 2016-01-29 14:29 MENDELSSOHN BARTHOLDY, Felix (1809–47) Quartet No.5 in E flat major 34'50 Op.44 No.3, MWV R28 (1837–38) 1 I. Allegro vivace 13'22 2 II. Scherzo. Assai leggiero e vivace 4'05 3 III. Adagio non troppo 8'34 4 IV. Molto allegro con fuoco 8'40 from Four Pieces for String Quartet, Op.81 5 3. Capriccio (Andante con moto – Allegro fugato assai vivace) in E minor, MWV R32 (1843) 5'37 6 4. Fugue (A tempo ordinario) in E flat major, MWV R23 (1827) 5'00 Quartet No.6 in F minor, Op.80, MWV R37 (1847) 25'02 7 I. Allegro vivace assai – Presto 7'05 8 II. Allegro assai 4'14 9 III. Adagio 7'52 10 IV. Finale. Allegro molto 5'44 TT: 71'17 Escher String Quartet Adam Barnett-Hart violin · Aaron Boyd violin Pierre Lapointe viola · Dane Johansen cello 3 he quartet has always been regarded as the purest and noblest of mu sical genres, which in particular heightens, educates, refines our appre cia tion ‘Tof music and, with the tiniest of means, achieves the ut most. Its clarity and transparency, which no trickery can cloak, make quartet music the surest yard- stick for measuring genuine composers; in renouncing the sensual lures of sound effects and contrasts, it highlights the gift of musical invention and the art of exploiting a musical idea. -

The Seventh Season Being Mendelssohn CHAMBER MUSIC FESTIVAL and INSTITUTE July 17–August 8, 2009 David Finckel and Wu Han, Artistic Directors

The Seventh Season Being Mendelssohn CHAMBER MUSIC FESTIVAL AND INSTITUTE July 17–August 8, 2009 David Finckel and Wu Han, Artistic Directors Music@Menlo Being Mendelssohn the seventh season july 17–august 8, 2009 david finckel and wu han, artistic directors Contents 3 A Message from the Artistic Directors 5 Welcome from the Executive Director 7 Being Mendelssohn: Program Information 8 Essay: “Mendelssohn and Us” by R. Larry Todd 10 Encounters I–IV 12 Concert Programs I–V 29 Mendelssohn String Quartet Cycle I–III 35 Carte Blanche Concerts I–III 46 Chamber Music Institute 48 Prelude Performances 54 Koret Young Performers Concerts 57 Open House 58 Café Conversations 59 Master Classes 60 Visual Arts and the Festival 61 Artist and Faculty Biographies 74 Glossary 76 Join Music@Menlo 80 Acknowledgments 81 Ticket and Performance Information 83 Music@Menlo LIVE 84 Festival Calendar Cover artwork: untitled, 2009, oil on card stock, 40 x 40 cm by Theo Noll. Inside (p. 60): paintings by Theo Noll. Images on pp. 1, 7, 9 (Mendelssohn portrait), 10 (Mendelssohn portrait), 12, 16, 19, 23, and 26 courtesy of Bildarchiv Preussischer Kulturbesitz/Art Resource, NY. Images on pp. 10–11 (landscape) courtesy of Lebrecht Music and Arts; (insects, Mendelssohn on deathbed) courtesy of the Bridgeman Art Library. Photographs on pp. 30–31, Pacifica Quartet, courtesy of the Chamber Music Society of Lincoln Center. Theo Noll (p. 60): Simone Geissler. Bruce Adolphe (p. 61), Orli Shaham (p. 66), Da-Hong Seetoo (p. 83): Christian Steiner. William Bennett (p. 62): Ralph Granich. Hasse Borup (p. 62): Mary Noble Ours. -

John Gilhooly

A RARE INTERVIEW WITH JOHN GILHOOLY PLUS SPRING SCHUMANN PERSPECTIVES 2018 PEKKA KUUSISTO RESIDENCY JAN ÁČEK’S INSTRUMENTAL WORKS FRIENDS OF OF FRIENDS YOUR 2018/19 DATES INSIDE John Gilhooly’s vision for Wigmore Hall extends far into the next decade and beyond. He outlines further dynamic plans to develop artistic quality, financial stability and audience diversity. JOHN GILHOOLY IN CONVERSATION WITH CLASSICAL MUSIC JOURNALIST, ANDY STEWART. FUTURE COMMITMENT “I’M IN FOR THE LONG HAUL!” Wigmore Hall’s Chief Executive and Artistic Director delivers the makings of a modern manifesto in eight words. “This is no longer a hall for hire,” says John Gilhooly, “or at least, very rarely”. The headline leads to a summary of the new season, its themed concerts, special projects, artist residencies and Learning events, programmed in partnership with an array of world-class artists and promoted by Wigmore Hall. It also prefaces a statement of intent by a well-liked, creative leader committed to remain in post throughout the next decade, determined to realise a long list of plans and priorities. “I am excited about the future,” says John, “and I am very grateful for the ongoing help and support of the loyal audience who have done so much already, especially in the past 15 years.” 2 WWW.WIGMORE-HALL.ORG.UK | FRIENDS OFFICE 020 7258 8230 ‘ The Hall is a magical place. I love it. I love the artists, © Kaupo Kikkas © Kaupo the music, the staff and the A glance at next audience. There are so many John’s plans for season’s highlights the Hall pave the confirms the strength characters who add to the way for another 15 and quality of an colour and complexion of the years of success. -

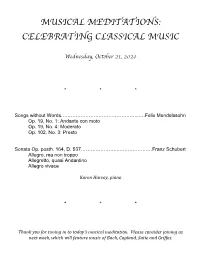

Musmeds&Notes-October 21, 2020

MUSICAL MEDITATIONS: CELEBRATING CLASSICAL MUSIC Wednesday, October 21, 2020 * * * Songs without Words………………………………………...….Felix Mendelssohn Op. 19, No. 1: Andante con moto Op. 19, No. 4: Moderato Op. 102, No. 3: Presto Sonata Op. posth. 164, D. 537…………………..…………………Franz Schubert Allegro, ma non troppo Allegretto, quasi Andantino Allegro vivace Karen Harvey, piano * * * Thank you for tuning in to today’s musical meditation. Please consider joining us next week, which will feature music of Bach, Copland, Satie and Griffes. Notes on today’s music Jakob Ludwig Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy (February 3, 1809 – November 4, 1847), a.k.a. Felix Mendelssohn, was a German composer, pianist, organist and conductor of the early Romantic period. Mendelssohn's compositions incluDe symphonies, concertos, piano music, organ music and chamber music. His best-known works incluDe the overture and incidental music for A Midsummer Night's Dream (containing the famous Wedding March), the Italian Symphony, the Scottish Symphony, the oratorio St. Paul, the oratorio Elijah, the overture The Hebrides, the mature Violin Concerto and the String Octet. The meloDy for the Christmas carol "Hark! The HeralD Angels Sing" is also his. Songs Without Words are his most famous solo piano compositions. A grandson of the philosopher Moses MenDelssohn, Felix MenDelssohn was born into a prominent Jewish family, anD though he was recogniseD early as a musical proDigy, his parents were cautious and did not seek to capitalise on his talent. MenDelssohn enjoyeD early success in Germany, anD singlehandedly reviveD interest in the music of Johann Sebastian Bach with his performance of the St. Matthew Passion in 1829. -

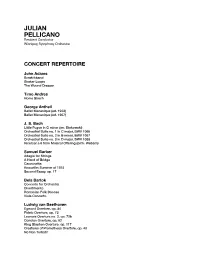

Julian Pellicano Repertoire Copy

JULIAN PELLICANO Resident Conductor Winnipeg Symphony Orchestra CONCERT REPERTOIRE John Adams Scratchband Shaker Loops The Wound Dresser Timo Andres Home Strech George Antheil Ballet Mecanique (ed. 1923) Ballet Mecanique (ed. 1957) J. S. Bach Little Fugue in G minor (arr. Stokowski) Orchestral Suite no. 1 in C major, BWV 1066 Orchestral Suite no. 2 in B minor, BWV 1067 Orchestral Suite no. 3 in D major, BWV 1068 Ricercar a 6 from Musical Offering (orch. Webern) Samuel Barber Adagio for Strings A Hand of Bridge Canzonetta Knoxville: Summer of 1915 Second Essay, op. 17 Bela Bartok Concerto for Orchestra Divertimento Romanian Folk Dances Viola Concerto Ludwig van Beethoven Egmont Overture, op. 84 Fidelo Overture, op. 72 Leonore Overture no. 3, op. 72b Coriolan Overture, op. 62 KIng Stephen Overture, op. 117 Creatures of Prometheus Overture, op. 43 No Non Turbati! Octet, op. 103 Piano Concerti no. 1 - 5 Symphonies no. 1 - 9 Violin Concerto, op. 61 Alban Berg Drei Orchesterstucke, op. 6 Hector Berlioz Roman Carnival Overture Royal Hunt and Storm from Les Troyens Symphonie Fantastique, op. 14 Scene D’Amour from Romeo and Juliet Leonard Bernstein Overture to Candide On the Town: Three Dance Episodes Overture to WEst Side Story (ed. Peress) Symphonic Dances from West Side Story Slava! Georges Bizet Carmen Suite no. 1 Carmen Suite no. 2 L’Arlesienne Suite no. 1 L’Arlesienne Suite no. 2 Alexander Borodin In the Steppes of Central Asia Polovtsian Dances Symphony no. 2 Johannes Brahms Academic Festival Overture, op. 80 Hungarian Dances no. 1,3,5,6,20,21 Symphonies no. -

Even String Quartets— No Longer Sit in Chairs When

It’s not a huge FINE, auprising, but a number of Upst ensembles—nding even string quartets— no longer sit in chairs when EMPIRE BRASS performing. What’s it all about? 26 may/june 2010 a ENSEMBLES ike most art forms, chamber music PROS by Judith Kogan performance has evolved to reflect For many people, it’s simply more com- Upst ndingchanges in society and technology. fortable to play standing up. It’s how we’re L As instruments developed greater power to taught to play and how we perform as solo- project, performances moved from small ists. Standing, it’s easier to establish good chambers to larger spaces, where professional posture with the instrument. musicians played to paying audiences. New Standing also allows freedom to express instrumentations, such as the saxophone with the whole body. With arms, shoulders quartet and the percussion ensemble, and waist liberated, a player’s range of motion emerged. By the late twentieth century, expands. For wind players, there’s better composers had recast what was once thought air flow. The ability to turn the whole body of as “intimate musical conversation” to in- makes it easier to communicate with other corporate abrasive electronically-produced ensemble members and the audience. One sonorities. Some works called for musi- arguably feels the rhythm of a piece better cians to wear headphones with click tracks, on one’s feet, and, perhaps unconsciously, preventing them from hearing each other. produces a bigger, fatter sound. Sometimes they couldn’t even hear them- In terms of acoustics, sound travels farther selves. -

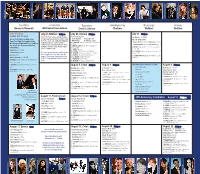

Calendarmailerfinal:Layout 1

Jon Manasse Boston Cello Quartet Julian Schwarz Jon Nakamatsu Martin Beaver Amit Peled Cypress String Quartet Stephanie Chase Yeesun Kim Curtis on Tour Emerson String Quartet Natasha Paremski Noreen Polera Sunday Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday Dennis & Yarmouth Wellfleet & Provincetown Cotuit & Orleans Chatham Wellfleet Wellfleet Cape Cod Gala July 21, Wellfleet 7:30pm July 29, Orleans 7:30pm July 31 7:30pm Sunday, July 27 ~ 6pm Curtis On Tour features a string chamber Boston Cello Quartet Jon Manasse, CLARINET Blaise Déjardin Adam Esbensen Join us for a festive evening at our orchestra performing Antonio Vivaldi’s iconic Emerson String Quartet Cape Cod Gala! Featuring music by The Four Seasons paired with Ástor Piazzolla’s Mihail Jojatu Alexandre Lecarme tango masterpieces Cuatro Estaciones W.A. MOZART Overture to The Abduction from the Eugene Drucker, VIOLIN Philip Setzer, VIOLIN the Manasse/Nakamatsu Duo. Cocktails Seraglio Porteñas (The Four Seasons of Buenos Aires) Lawrence Dutton, VIOLA Paul Watkins, CELLO at 6, music at 6:45 followed by a full F. MENDELSSOHN Scherzo from A Midsummer buffet dinner. featuring celebrated Curtis alumna violinist Night’s Dream J. HAYDN String Quartet in G Minor; Opus 20 No. Elissa Lee Koljonen (’94). C. DEBUSSY Reverie 3, Hob. III.33 Jon Manasse, CLARINET D. POPPER Suite for Two Cellos, Opus 16 W. A. MOZART Quintet in A Major for Clarinet and The proceeds from this concert will help fund Jon Nakamatsu, PIANO E. CHABRIER España, rapsodie pour orchestra Strings, K. 581 Luis Ortiz, PIANO the restoration of the late 18th-early 19th J. WILLIAMS Theme from Angela’s Ashes century “Church Bass” that has been in the L. -

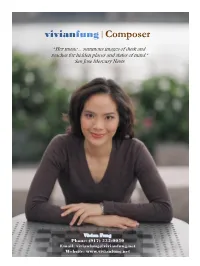

Vivianfung|Composer

vivianfung|Composer “Her music ... summons images of dusk and reaches for hidden places and states of mind.” San Jose Mercury News Vivian Fung Phone: (917) 535-0050 Email: [email protected] Website: www.vivianfung.net Vivian Fung has distinguished herself as a composer with a unique and powerful compositional voice. Since earning her doctorate from The Juilliard School in 2002, she has forged her own approach often merging western forms with non-western vivianfung|Composer influences such as Balinese and Javanese gamelan and folk songs from minority regions of China. The New “…as vital as encountering Steve Reich or the York Times has described her work as ―evocative,‖ Kronos for the first time.” and The Strad hails her Uighur-influenced music to be The Strad ―as vital as encountering Steve Reich or the Kronos for the first time.‖ Chicago Tribune described Fung‘s Yunnan Folk Songs as conveying ―a winning rawness that went beyond exoticism.‖ Fung has traveled extensively for her work. In 2004, she traveled to Bali, Indonesia Highlights of Fung's recent world as part of the Asia Pacific Performance Exchange premieres include: her Violin Concerto for Kristin Program, sponsored by the UCLA Center for Lee and Grammy nominated Metropolis Ensemble, Intercultural Performance. In summer 2010, as an Dust Devils commissioned by the Eastern Music ensemble member of Gamelan Dharma Swara, she Festival celebrating their 50th anniversary, Yunnan completed a performance tour of Bali including Folk Songs by Fulcrum Point New Music Project in competing in the Bali Arts Festival. Chicago; new choral works by the acclaimed Suwon Civic Chorale in South Korea; Chant by pianist Fung‘s works have increasingly Margaret Leng Tan at the Museum of Modern Art in become part of the core repertoire. -

Vivaldi Explosion Program

The following program notes may only be used in conjunction with the one-time streaming term for the corresponding Chamber Music Society of Lincoln Center (CMS) Front Row National program, with the following credit(s): Program notes by Laura Keller, CMS Editorial Manager © 2020 Chamber Music Society of Lincoln Center Any other use of these materials in connection with non-CMS concerts or events is prohibited. VIVALDI EXPLOSION PROGRAM ANTONIO VIVALDI (1678-1741) Sonata in A minor for Cello and Continuo, RV 43 (c. 1739) Largo Allegro Largo Allegro Efe Baltacigil, cello; Dane Johansen, cello; Paul O’Dette, lute; John Gibbons, harpsichord VIVALDI Concerto in G minor for Flute, Oboe, and Bassoon, RV 103 Allegro ma cantabile Largo Allegro non molto Sooyun Kim, flute; Stephen Taylor, oboe; Bram van Sambeek, bassoon VIVALDI Concerto in F major for Three Violins, Strings, and Continuo, RV 551 (1711) Allegro Andante Allegro Todd Phillips, violin; Bella Hristova, violin; Chad Hoopes, violin; Sean Lee, violin; Aaron Boyd, violin; Pierre Lapointe, viola; Timothy Eddy, cello; Anthony Manzo, bass; Michael Sponseller, harpsichord --INTERMISSION (Discussion with artists)-- VIVALDI Sonata in D minor for Two Violins and Continuo, RV 63, “La Follia” (published c. 1705) Adam Barnett-Hart, violin; Aaron Boyd, violin; Brook Speltz, cello; Jason Vieaux, guitar VIVALDI Concerto in D major for Mandolin, Strings, and Continuo, RV 93 (1730-31) Chamber Music Society of Lincoln Center Allegro giusto Largo Allegro Avi Avital, mandolin; Paul Huang, violin; Danbi Um, violin; Ani Kavafian, violin; Chad Hoopes, violin; Mihai Marica, cello; Daniel McDonough, cello; Anthony Manzo, bass; Jiayan Sun, harpsichord NOTES ON THE PROGRAM Violin virtuosity reached a new height around the year 1700.