JAN 21 RICMC Concert Program

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download Booklet

572813 bk Zemlinsky EU_572813 bk Zemlinsky EU 23/05/2013 13:45 Page 4 Escher String Quartet Alexander Adam Barnett-Hart, Violin I • Wu Jie, Violin II • Pierre Lapointe, Viola • Dane Johansen, Cello Championed by the Emerson String Quartet, the Escher String ZEMLINSKY Quartet players were BBC New Generation Artists from 2010- 2012, giving débuts at both the Wigmore Hall and the BBC Proms String Quartets • 1 at Cadogan Hall. In their home town of New York, the quartet recently completed a three-year Escher String Quartet Rising Stars residency at The Chamber Music Society of Lincoln Center. Within months of its inception in 2005, the Escher Quartet was invited by both Pinchas Zukerman and Itzhak Perlman to be Quartet-in-Residence at each artist’s summer festival: the Young Artists Programme at Canada’s National Arts Centre; and the Perlman Chamber Music Program on Shelter Island, NY. Photo: Henry Fair In addition, the quartet has collaborated with artists such as Andrés Diaz, Lawrence Dutton, Kurt Elling, Leon Fleisher, Anja Lechner, Vadim Gluzman, Angela Yoffe, Gary Hoffman, Joseph Kalichstein, Kurt Muroki, Joseph Silverstein, Khatia Buniatishvili, Benjamin Grosvenor and Matthew Hunt, as well pop folk singer-songwriter Luke Temple. Recent performances include appearances at the Cheltenham, Lichfield and City of London Festivals, the Auditorium du Louvre in Paris, 92nd Street Y in New York, the Kennedy Center in Washington DC and the Ravinia and Caramoor festivals. Elsewhere, the quartet undertook a tour of China including Beijing, Shanghai and Hangzhou, and made its Australian début with Brett Dean at the Perth International Arts Festival. -

Classical Series 1 2019/2020

classical series 2019/2020 season 1 classical series 2019/2020 Meet us at de Doelen! Bang in the middle of Rotterdam’s vibrant city centre and at a stone’s throw from the magnificent Central Station, you find concert hall de Doelen. A perfect architectural example of the Dutch post-war reconstruction era, as well as a veritable people’s palace, featuring international programming and festivals. Built in the sixties, its spacious state- of-the-art auditoria and foyers continue to make it look and feel like a timelessly modern and dynamic location indeed. De Doelen is home to the Rotterdam Philharmonic Orchestra, with the very young and talented conductor Lahav Shani at its helm. But that is not all! With over 600 concerts held annually, our programming is delightfully varied, ranging from true crowd-pullers to concerts catering to connoisseurs, and from children’s concerts to performances of world music, jazz and hip-hop. What’s more, de Doelen is the beating heart of renowned cultural festivals such as the IFFR, Poetry International, Rotterdam Unlimited, HipHopHouse’s Make A Scene and RPhO’s Gergiev Festival. Check this brochure for this season’s programme. You will hopefully be as thrilled as we are with what’s on offer. Meet us at de Doelen and enjoy! Janneke Staarink, director & de Doelen team Janneke Staarink © Sanne Donders classical series 3 contents classical series 2019/2020 season preface 3 Pierre-Laurent Aimard © Marco Borggreve Grupo Ruta de la Esclavitud © Claire Xavier classical series 6 - 29 suggestions per subject 30 chronological overview 32 piano great baroque ordering information 36 From classics to cross-overs: the versatility of the This series features great themes and signature baroque floor plans 38 piano takes centre stage. -

Escher String Quartet String Quartets: No

MENDELSSOHN · ESCHER STRING QUARTET STRING QUARTETS: NO. 5 IN E FLAT MAJOR & NO. 6 IN F MAJOR Front cover from left: Pierre Lapointe, Adam Barnett-Hart, Aaron Boyd, Dane Johansen BIS-2160 BIS-2160 booklet cover.indd 1 2016-01-29 14:29 MENDELSSOHN BARTHOLDY, Felix (1809–47) Quartet No.5 in E flat major 34'50 Op.44 No.3, MWV R28 (1837–38) 1 I. Allegro vivace 13'22 2 II. Scherzo. Assai leggiero e vivace 4'05 3 III. Adagio non troppo 8'34 4 IV. Molto allegro con fuoco 8'40 from Four Pieces for String Quartet, Op.81 5 3. Capriccio (Andante con moto – Allegro fugato assai vivace) in E minor, MWV R32 (1843) 5'37 6 4. Fugue (A tempo ordinario) in E flat major, MWV R23 (1827) 5'00 Quartet No.6 in F minor, Op.80, MWV R37 (1847) 25'02 7 I. Allegro vivace assai – Presto 7'05 8 II. Allegro assai 4'14 9 III. Adagio 7'52 10 IV. Finale. Allegro molto 5'44 TT: 71'17 Escher String Quartet Adam Barnett-Hart violin · Aaron Boyd violin Pierre Lapointe viola · Dane Johansen cello 3 he quartet has always been regarded as the purest and noblest of mu sical genres, which in particular heightens, educates, refines our appre cia tion ‘Tof music and, with the tiniest of means, achieves the ut most. Its clarity and transparency, which no trickery can cloak, make quartet music the surest yard- stick for measuring genuine composers; in renouncing the sensual lures of sound effects and contrasts, it highlights the gift of musical invention and the art of exploiting a musical idea. -

International Viola Congress

CONNECTING CULTURES AND GENERATIONS rd 43 International Viola Congress concerts workshops| masterclasses | lectures | viola orchestra Cremona, October 4 - 8, 2016 Calendar of Events Tuesday October 4 8:30 am Competition Registration, Sala Mercanti 4:00 pm Tymendorf-Zamarra Recital, Sala Maffei 9:30 am-12:30 pm Competition Semifinal,Teatro Filo 4:00 pm Stanisławska, Guzowska, Maliszewski 10:00 am Congress Registration, Sala Mercanti Recital, Auditorium 12:30 pm Openinig Ceremony, Auditorium 5:10 pm Bruno Giuranna Lecture-Recital, Auditorium 1:00 pm Russo Rossi Opening Recital, Auditorium 6:10 pm Ettore Causa Recital, Sala Maffei 2:00 pm-5:00 pm Competition Semifinal,Teatro Filo 8:30 pm Competition Final, S.Agostino Church 2:00 pm Dalton Lecture, Sala Maffei Post-concert Café Viola, Locanda il Bissone 3:00 pm AIV General Meeting, Sala Mercanti 5:10 pm Tabea Zimmermann Master Class, Sala Maffei Friday October 7 6:10 pm Alfonso Ghedin Discuss Viola Set-Up, Sala Maffei 9:00 am ESMAE, Sala Maffei 8:30 pm Opening Concert, Auditorium 9:00 am Shore Workshop, Auditorium Post-concert Café Viola, Locanda il Bissone 10:00 am Giallombardo, Kipelainen Recital, Auditorium Wednesday October 5 11:10 am Palmizio Recital, Sala Maffei 12:10 pm Eckert Recital, Sala Maffei 9:00 am Kosmala Workshop, Sala Maffei 9:00 am Cuneo Workshop, Auditorium 12:10 pm Rotterdam/The Hague Recital, Auditorium 10:00 am Alvarez, Richman, Gerling Recital, Sala Maffei 1:00 pm Street Concerts, Various Locations 11:10 am Tabea Zimmermann Recital, Museo del Violino 2:00 pm Viola Orchestra -

Schumann Quartett

Candlelight Concert Society Presents SCHUMANN QUARTETT ERIK SCHUMANN, violin KEN SCHUMANN, violin LIISA RANDALU, viola MARK SCHUMANN, cello Saturday, February 22, 2020, 7:30 pm Smith Theatre–Horowitz Visual & Performing Arts Center Howard Community College This performance is sponsored by Rosalie Lijinsky Chadwick in memory of William Lijinsky WOLFGANG AMADEUS MOZART (1756–1791) Quartet in D major, K. 499, “Hoffmeister” Allegretto Menuetto: Allegretto Adagio Allegro DMITRI SHOSTAKOVICH (1906–1975) Quartet no. 9 in E-flat Major, op. 117 Moderato con moto Adagio Allegretto Adagio Allegro Intermission BEDŘICH SMETANA (1824–1884) Quartet no. 1 in E minor, “From my Life” Allegro vivo appassionato Allegro moderato alla Polka Largo sostenuto Vivace Discography: BERLIN CLASSICS Management: ARTS MANAGEMENT GROUP, INC., https://www.artsmg.com/ deepening plot. Some of Mozart’s densest coun- Program Notes terpoint appears in the Menuetto, which is at the same time intense and elegant. Following traditional Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756–1791) minuet and trio form, the robust initial repeated sec- QUARTET IN D MAJOR, K. 499, “HOFFMEISTER” tions give over to a trio, which in this case introduces a tentative element. The trio ends one beat too The publisher and skilled am- early, as if the composer were tripping over him- ateur violinist Franz Anton self in his eagerness to get back to the confidence Hoffmeister (1754-1812) of the minuet. A slow movement, marked Adagio, was a friend, colleague, and brings repose in the form of a homophonic texture, benefactor of Mozart. In but there is a hint of melancholy in the chromatic 1785, Hoffmeister agreed ornamentation and chord progressions. -

John Gilhooly

A RARE INTERVIEW WITH JOHN GILHOOLY PLUS SPRING SCHUMANN PERSPECTIVES 2018 PEKKA KUUSISTO RESIDENCY JAN ÁČEK’S INSTRUMENTAL WORKS FRIENDS OF OF FRIENDS YOUR 2018/19 DATES INSIDE John Gilhooly’s vision for Wigmore Hall extends far into the next decade and beyond. He outlines further dynamic plans to develop artistic quality, financial stability and audience diversity. JOHN GILHOOLY IN CONVERSATION WITH CLASSICAL MUSIC JOURNALIST, ANDY STEWART. FUTURE COMMITMENT “I’M IN FOR THE LONG HAUL!” Wigmore Hall’s Chief Executive and Artistic Director delivers the makings of a modern manifesto in eight words. “This is no longer a hall for hire,” says John Gilhooly, “or at least, very rarely”. The headline leads to a summary of the new season, its themed concerts, special projects, artist residencies and Learning events, programmed in partnership with an array of world-class artists and promoted by Wigmore Hall. It also prefaces a statement of intent by a well-liked, creative leader committed to remain in post throughout the next decade, determined to realise a long list of plans and priorities. “I am excited about the future,” says John, “and I am very grateful for the ongoing help and support of the loyal audience who have done so much already, especially in the past 15 years.” 2 WWW.WIGMORE-HALL.ORG.UK | FRIENDS OFFICE 020 7258 8230 ‘ The Hall is a magical place. I love it. I love the artists, © Kaupo Kikkas © Kaupo the music, the staff and the A glance at next audience. There are so many John’s plans for season’s highlights the Hall pave the confirms the strength characters who add to the way for another 15 and quality of an colour and complexion of the years of success. -

Venice Music Biennale Announces 2021 Programme, ‘Choruses’, September 17-26

VENICE MUSIC BIENNALE ANNOUNCES 2021 PROGRAMME, ‘CHORUSES’, SEPTEMBER 17-26 FIRST MUSIC BIENNALE UNDER ARTISTIC DIRECTOR LUCIA RONCHETTI FIFTEEN WORLD PREMIERES TO BE GIVEN KAIJA SAARIAHO RECEIVES GOLDEN LION LIFETIME ACHIEVEMENT AWARD Lucia Ronchetti. Photo credit: Vanessa Francia The programme for the 2021 Venice Music Biennale, one of the six Biennale di Venezia that showcase the best in contemporary Architecture, Art, Dance, Film, Music and Theatre, has been announced by Artistic Director Lucia Ronchetti. For her first Biennale as Artistic Director the Italian composer is presenting 15 world premieres over 10 days of performances across Venice under the heading of ‘Choruses.’ ‘Choruses’ will focus on contemporary choral writing through performances of new commissions and some of the most important works of the last 50 years that explore the human voice. The Venice Music Biennale 2021 is fostering a dialogue between the Venetian past and the present, and the possible renaissance of vocal polyphony through performances from major Venetian organisations across the city. The 65th Music Biennale will welcome major European vocal and choral ensembles such as Theatre of Voices from Copenhagen, Neue Vocalsolisten from Stuttgart, Accentus choir from Paris, vocal ensemble Sequenza 9.3 from Paris and SWR Vokalensemble from Stuttgart, as well as the renowned historical Venetian choirs the Cappella Marciana di San Marco and the choir of the Teatro La Fenice. The Festival will open at the Teatro La Fenice with a performance of Oltra mar for choir and orchestra by Kaija Saariaho, winner of the Golden Lion for Music, whose chamber work Only the sound remains will also be presented at the Teatro Malibran. -

Even String Quartets— No Longer Sit in Chairs When

It’s not a huge FINE, auprising, but a number of Upst ensembles—nding even string quartets— no longer sit in chairs when EMPIRE BRASS performing. What’s it all about? 26 may/june 2010 a ENSEMBLES ike most art forms, chamber music PROS by Judith Kogan performance has evolved to reflect For many people, it’s simply more com- Upst ndingchanges in society and technology. fortable to play standing up. It’s how we’re L As instruments developed greater power to taught to play and how we perform as solo- project, performances moved from small ists. Standing, it’s easier to establish good chambers to larger spaces, where professional posture with the instrument. musicians played to paying audiences. New Standing also allows freedom to express instrumentations, such as the saxophone with the whole body. With arms, shoulders quartet and the percussion ensemble, and waist liberated, a player’s range of motion emerged. By the late twentieth century, expands. For wind players, there’s better composers had recast what was once thought air flow. The ability to turn the whole body of as “intimate musical conversation” to in- makes it easier to communicate with other corporate abrasive electronically-produced ensemble members and the audience. One sonorities. Some works called for musi- arguably feels the rhythm of a piece better cians to wear headphones with click tracks, on one’s feet, and, perhaps unconsciously, preventing them from hearing each other. produces a bigger, fatter sound. Sometimes they couldn’t even hear them- In terms of acoustics, sound travels farther selves. -

Calendarmailerfinal:Layout 1

Jon Manasse Boston Cello Quartet Julian Schwarz Jon Nakamatsu Martin Beaver Amit Peled Cypress String Quartet Stephanie Chase Yeesun Kim Curtis on Tour Emerson String Quartet Natasha Paremski Noreen Polera Sunday Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday Dennis & Yarmouth Wellfleet & Provincetown Cotuit & Orleans Chatham Wellfleet Wellfleet Cape Cod Gala July 21, Wellfleet 7:30pm July 29, Orleans 7:30pm July 31 7:30pm Sunday, July 27 ~ 6pm Curtis On Tour features a string chamber Boston Cello Quartet Jon Manasse, CLARINET Blaise Déjardin Adam Esbensen Join us for a festive evening at our orchestra performing Antonio Vivaldi’s iconic Emerson String Quartet Cape Cod Gala! Featuring music by The Four Seasons paired with Ástor Piazzolla’s Mihail Jojatu Alexandre Lecarme tango masterpieces Cuatro Estaciones W.A. MOZART Overture to The Abduction from the Eugene Drucker, VIOLIN Philip Setzer, VIOLIN the Manasse/Nakamatsu Duo. Cocktails Seraglio Porteñas (The Four Seasons of Buenos Aires) Lawrence Dutton, VIOLA Paul Watkins, CELLO at 6, music at 6:45 followed by a full F. MENDELSSOHN Scherzo from A Midsummer buffet dinner. featuring celebrated Curtis alumna violinist Night’s Dream J. HAYDN String Quartet in G Minor; Opus 20 No. Elissa Lee Koljonen (’94). C. DEBUSSY Reverie 3, Hob. III.33 Jon Manasse, CLARINET D. POPPER Suite for Two Cellos, Opus 16 W. A. MOZART Quintet in A Major for Clarinet and The proceeds from this concert will help fund Jon Nakamatsu, PIANO E. CHABRIER España, rapsodie pour orchestra Strings, K. 581 Luis Ortiz, PIANO the restoration of the late 18th-early 19th J. WILLIAMS Theme from Angela’s Ashes century “Church Bass” that has been in the L. -

CHAMBER MUSIC SOCIETY of LINCOLN CENTER Broadcast Schedule — Summer 2018

CHAMBER MUSIC SOCIETY OF LINCOLN CENTER Broadcast Schedule — Summer 2018 Please note: these programs are subject to change; please consult cue sheet for details. PROGRAM #: CMS 17-41 RELEASE: July 3, 2018 Beauty and the Beast Haydn Quartet in F major for Strings, Op. 50, No. 5, “The Dream” Orion String Quartet, Todd Phillips, Violin I; Daniel Phillips, Violin II; Steven Tenenbom, Viola; Timothy Eddy, Cello Bloch Quintet No. 1 for Piano, Two Violins, Viola, and Cello Michael Brown, Piano; Kristin Lee, Violin I; Danbi Um, Violin II; Matthew Lipman, Viola; Nicholas Canellakis, Cello PROGRAM #: CMS 17-42 RELEASE: July 10, 2018 Small to Big Ravel Sonata for Violin and Cello Yura Lee, Violin; Jakob Koranyi, Cello Vierne Quintet for Piano, Two Violins, Viola, and Cello, Op. 42 Gilles Vonsattel, Piano; Danish String Quartet PROGRAM #: CMS 17-43 RELEASE: July 17, 2018 Mendelssohn and Schumann Mendelssohn Quartet in F minor for Strings, Op. 80 (ATH) Schumann Quartet: Erik Schumann, Violin I; Ken Schumann, Violin II; Liisa Randalu, Viola; Mark Schumann, Cello Schumann Quartet in E- Flat major for Piano, Violin, Viola, and Cello, Op. 47 (ATH) Wu Qian, Piano; Alexander Sitkovetsky, Violin; Yura Lee, Viola; Jan Vogler, Cello PROGRAM #: CMS 17-44 RELEASE: July 24, 2018 Britten and Dvořák Britten Canticle II: Abraham and Isaac for Countertenor, Tenor, and Piano, Op. 51 Daniel Taylor, countertenor; Anthony Griffey, tenor; Gloria Chien, piano Dvořák Trio in G minor for Piano, Violin, and Cello, Op. 26 Gloria Chien, piano; Nicolas Dautricourt, violin; Nicolas -

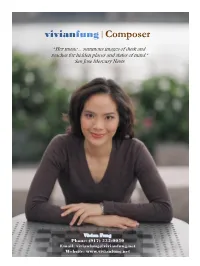

Vivianfung|Composer

vivianfung|Composer “Her music ... summons images of dusk and reaches for hidden places and states of mind.” San Jose Mercury News Vivian Fung Phone: (917) 535-0050 Email: [email protected] Website: www.vivianfung.net Vivian Fung has distinguished herself as a composer with a unique and powerful compositional voice. Since earning her doctorate from The Juilliard School in 2002, she has forged her own approach often merging western forms with non-western vivianfung|Composer influences such as Balinese and Javanese gamelan and folk songs from minority regions of China. The New “…as vital as encountering Steve Reich or the York Times has described her work as ―evocative,‖ Kronos for the first time.” and The Strad hails her Uighur-influenced music to be The Strad ―as vital as encountering Steve Reich or the Kronos for the first time.‖ Chicago Tribune described Fung‘s Yunnan Folk Songs as conveying ―a winning rawness that went beyond exoticism.‖ Fung has traveled extensively for her work. In 2004, she traveled to Bali, Indonesia Highlights of Fung's recent world as part of the Asia Pacific Performance Exchange premieres include: her Violin Concerto for Kristin Program, sponsored by the UCLA Center for Lee and Grammy nominated Metropolis Ensemble, Intercultural Performance. In summer 2010, as an Dust Devils commissioned by the Eastern Music ensemble member of Gamelan Dharma Swara, she Festival celebrating their 50th anniversary, Yunnan completed a performance tour of Bali including Folk Songs by Fulcrum Point New Music Project in competing in the Bali Arts Festival. Chicago; new choral works by the acclaimed Suwon Civic Chorale in South Korea; Chant by pianist Fung‘s works have increasingly Margaret Leng Tan at the Museum of Modern Art in become part of the core repertoire. -

Vivaldi Explosion Program

The following program notes may only be used in conjunction with the one-time streaming term for the corresponding Chamber Music Society of Lincoln Center (CMS) Front Row National program, with the following credit(s): Program notes by Laura Keller, CMS Editorial Manager © 2020 Chamber Music Society of Lincoln Center Any other use of these materials in connection with non-CMS concerts or events is prohibited. VIVALDI EXPLOSION PROGRAM ANTONIO VIVALDI (1678-1741) Sonata in A minor for Cello and Continuo, RV 43 (c. 1739) Largo Allegro Largo Allegro Efe Baltacigil, cello; Dane Johansen, cello; Paul O’Dette, lute; John Gibbons, harpsichord VIVALDI Concerto in G minor for Flute, Oboe, and Bassoon, RV 103 Allegro ma cantabile Largo Allegro non molto Sooyun Kim, flute; Stephen Taylor, oboe; Bram van Sambeek, bassoon VIVALDI Concerto in F major for Three Violins, Strings, and Continuo, RV 551 (1711) Allegro Andante Allegro Todd Phillips, violin; Bella Hristova, violin; Chad Hoopes, violin; Sean Lee, violin; Aaron Boyd, violin; Pierre Lapointe, viola; Timothy Eddy, cello; Anthony Manzo, bass; Michael Sponseller, harpsichord --INTERMISSION (Discussion with artists)-- VIVALDI Sonata in D minor for Two Violins and Continuo, RV 63, “La Follia” (published c. 1705) Adam Barnett-Hart, violin; Aaron Boyd, violin; Brook Speltz, cello; Jason Vieaux, guitar VIVALDI Concerto in D major for Mandolin, Strings, and Continuo, RV 93 (1730-31) Chamber Music Society of Lincoln Center Allegro giusto Largo Allegro Avi Avital, mandolin; Paul Huang, violin; Danbi Um, violin; Ani Kavafian, violin; Chad Hoopes, violin; Mihai Marica, cello; Daniel McDonough, cello; Anthony Manzo, bass; Jiayan Sun, harpsichord NOTES ON THE PROGRAM Violin virtuosity reached a new height around the year 1700.