Population Ecology and Summer Habitat Selection of Mule Deer in the White Mountains: Implications of Changing Landscapes and Variable Climate

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 Trans-Sierra Ranges Guide No. 1.6 White Mountain Peak

1 TRANS-SIERRA RANGES GUIDE NO. 1.6 WHITE MOUNTAIN PEAK 14246 FEET CLASS 1 MILEAGE: 275 miles of paved road, 16 miles of excellent dirt road DRIVE: From US Highway 395 at Big Pine, CA. turn right (E) on paved State Route 168. At a fork in 2.2 miles bear left (right will put you on the Waucoba-Saline Valley Road) and drive 10.8 miles to the paved, signed White Mountain Road. Turn left (N) and drive 10.3 miles to the end of pavement at the signed Schulman Grove. Continuing N on the excellent dirt road and following signs toward Patriarch Grove, drive 16 miles to a locked gate at 11680 feet elevation, passing the turnoff for Patriarch Grove approximately 12 miles from the end of pavement. Park. CLIMB: Hike up the road past the locked gate for 2 miles to the University of California's Barcroft Laboratory at 12,400 feet elevation. From the laboratory, continue following the road N for 0.5 miles as it climbs more steeply now to a flat spot at approximately the 12,800 foot level near an astronomical observatory. From this vantage point White Mountain can be clearly seen as the prominent red and black colored peak to the north, 5 miles distant via the road. Continue hiking the road N as it drops slightly to an expansive plateau and then gently rises to a spot just W of point 13189. Here, follow the road as it turns W and drops sharply some 250 feet to a saddle before continuing its long switchbacking path to the summit. -

California's Fourteeners

California’s Fourteeners Hikes to Climbs Sean O’Rourke Cover photograph: Thunderbolt Peak from the Paliasde Traverse. Frontispiece: Polemonium Peak’s east ridge. Copyright © 2016 by Sean O’Rourke. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form without express permission from the author. ISBN 978-0-98557-841-1 Contents 1 Introduction 1 1.1 Who should read this .......................... 1 1.2 Route difficulty ............................. 2 1.3 Route points .............................. 3 1.4 Safety and preparedness ........................ 4 1.5 Climbing season ............................ 7 1.6 Coming from Colorado ........................ 7 2 Mount Langley 9 2.1 Southwest slope ............................ 10 2.2 Tuttle Creek ............................... 11 3 Mount Muir 16 3.1 Whitney trail .............................. 17 4 Mount Whitney 18 4.1 Whitney trail .............................. 19 4.2 Mountaineer’s route .......................... 20 4.3 East buttress *Classic* ......................... 21 5 Mount Russell 24 5.1 East ridge *Classic* ........................... 25 5.2 South Face ............................... 26 5.3 North Arête ............................... 26 6 Mount Williamson 29 6.1 West chute ............................... 30 7 Mount Tyndall 31 7.1 North rib ................................ 32 7.2 Northwest ridge ............................ 32 8 Split Mountain 36 8.1 North slope ............................... 37 i 8.2 East Couloir .............................. 37 8.3 St. Jean Couloir -

United States Department of the Interior Geological Survey

UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Bibliographies and location maps of publications on aeromagnetic and aeroradiometric surveys for the states west of approximately 104° longitude (exclusive of Hawaii and Alaska) by Patricia L. Hill Open-File Report 91-370-A 1991 This report is preliminary and has not been reviewed for conformity with U.S. Geological Survey editorial standards. TABLE OF CONTENTS Page General Information.................................................... 2 Arizona................................................................ 4 California............................................................. 18 Colorado............................................................... 41 Idaho.................................................................. 54 Montana................................................................ 67 Nevada................................................................. 80 New Mexico ............................................................. 101 Oregon................................................................. 113 Utah................................................................... 122 Washington............................................................. 135 Wyoming................................................................ 145 Western Area DOE-NURE .................................................. 153 rev. 3-1-91 GENERAL INFORMATION FOR THE AEROMAGNETIC AND AERORADIOMETRIC INDEXES Bibliographies and location maps of selected publications containing aeromagnetic -

Plant Ecological Research in the White Mountains, Harold A

* University of California, Berkeley Supported under NASA Grant-GR-05-003-018 ,Formerly NaG-39'r FINAL TECHNICAL REPORT "AR (NASA-CR-138137) WHITE 11OUTAIN RESEARCH N74-22097 STATION: 25 YEARS OF HIGH-ALTITUDE RESEARCH Final Technical Report (California Univ.) 62 p HC $6.25 Unclas CSCL,-141 G3/14 __16056 univrs Ca orias ~~ 01i ff1 '~'' 0 Abv: a o aayisapaauhieMunan ek Cove phoo:ountin Wite Pak rom istat rok oucroping 37'40' 18'20' 1I8* 0' .- Lone Tree CrekN-SUMMIT LABORATORY a WHITE MOUNTAIN PEAK, 14246 1 o - HIGH ALTITUDE7 RESEARCH AREA BARCROFT LABORATORY MAedo . Barcrot,. 13023 UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA L g WHITE MOUNTAIN RESEARCH STATION Loe Eva Belle Mine AND VICINITY 100i '- , 0 1 2 3 4 5 -Plute Mountain, 12555'A Miles <f r- Coftonwood Contour interval1000 feet Sheep Mountain, 12487 Sre*kPrimitive Area Campito Meadow - 3730 Compito Mountain, 11543'A 10150 r i Prospector Meadow CROOKED CREEK LABORATORY Co l iforni ElectrC po 122 OM Bianco Mountain 1178 MONO COUNTYthe WHITE MOUNTAIN INYO COUNTY C, ou Schulm n Memoril o It Is andertWhere RnchWhy .' t Spring LAWSorganizedCalifornia,researchunit of the University Californiaofthe Summtrit Laboratory atop White Mountain Peak at11033 head- of the Assistant Director.ninAdministrative OwensValley Laboratory, atmileseastofBishop an vision BISOPOWENS VALLEY LABORATORY The WhiteResearch Mountain Station is a statewide Barcroft Laboratory at an elevation of 12,470 feet; and A history of the first 25 years of the WHITE MOUNTAIN RESEARCH STA TION by some Locatedthe vicinity in of Bishop, California, the sta- The Stationof laboratoriesthe scientists are who manned made the that year history round Where It Is and Why The White Mountain Research Station is a statewide Barcroft Laboratory at an elevation of 12,470 feet; and organized research unit of the University of California, the Summit Laboratory atop White Mountain Peak at toryestablished facilities for for two any purposes: qualified (1) research to provide investigator labora- anabove elevation 10,000 feetof 14,250are within feet. -

Wallrocks of the Central Sierra Nevada Batholith, California: a Collage of Accreted Tectono-Stratigraphic Terranes

Wallrocks of the Central Sierra Nevada Batholith, California: A Collage of Accreted Tectono-Stratigraphic Terranes GEOLOGICAL SURVEY PROFESSIONAL PAPER 1255 Wallrocks of the Central Sierra Nevada Batholith, California: A Collage of Accreted Tectono-Stratigraphic Terranes By WARREN J. NOKLEBERG GEOLOGICAL SURVEY PROFESSIONAL PAPER 1255 UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE, WASHINGTON : 1983 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR JAMES G. WATT, Secretary GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Dallas L. Peck, Director Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Nokleberg, Warren J. Wallrocks of the central Sierra Nevada batholith, California. (Geological Survey Professional Paper 1255) Bibliography: 28 p. Supt. of Doca. No.: I 19.16:1255 1. Batholiths Sierra Nevada Mountains (Calif, and Nev.) I. Title. II. Series. QE461.N64 552'.3 81-607153 AACR2 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Washington, D.C. 20402 CONTENTS Page Abstract .................................... 1 Cretaceous metavolcanic rocks ..................... 14 Introduction .................................. 1 Occurrence ............................... 14 Definitions ................................ 2 Stratigraphy and structure .................... 14 Acknowledgments ........................... 2 Kings terrane ................................ 14 Relation of multiple regional deformation to terrane Occurrence ............................... 14 accretion .................................. 2 Stratigraphy .............................. 15 Relation of terranes -

Mountain Views

Mountain Views Th e Newsletter of the Consortium for Integrated Climate Research in Western Mountains CIRMOUNT Informing the Mountain Research Community Vol. 8, No. 2 November 2014 White Mountain Peak as seen from Sherwin Grade north of Bishop, CA. Photo: Kelly Redmond Editor: Connie Millar, USDA Forest Service, Pacifi c Southwest Research Station, Albany, California Layout and Graphic Design: Diane Delany, USDA Forest Service, Pacifi c Southwest Research Station, Albany, California Front Cover: Rock formations, Snow Valley State Park, near St George, Utah. Photo: Kelly Redmond Back Cover: Clouds on Piegan Pass, Glacier National Park, Montana. Photo: Martha Apple Read about the contributing artists on page 71. Mountain Views The Newslett er of the Consortium for Integrated Climate Research in Western Mountains CIRMOUNT Volume 8, No 2, November 2014 www.fs.fed.us/psw/cirmount/ Table of Contents Th e Mountain Views Newsletter Connie Millar 1 Articles Parque Nacional Nevado de Tres Cruces, Chile: A Signifi cant Philip Rundel and Catherine Kleier 2 Coldspot of Biodiversity in a High Andean Ecosystem Th e Mountain Invasion Research Network (MIREN), reproduced Christoph Kueff er, Curtis Daehler, Hansjörg Dietz, Keith 7 from GAIA Zeitschrift McDougall, Catherine Parks, Anibal Pauchard, Lisa Rew, and the MIREN Consortium MtnClim 2014: A Report on the Tenth Anniversary Conference; Connie Millar 10 September 14-18, 2014, Midway, Utah Post-MtnClim Workshop for Resource Managers, Midway, Utah; Holly Hadley 19 September 18, 2014 Summary of Summaries: -

Interpreting the Timberline: an Aid to Help Park Naturalists to Acquaint Visitors with the Subalpine-Alpine Ecotone of Western North America

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 1966 Interpreting the timberline: An aid to help park naturalists to acquaint visitors with the subalpine-alpine ecotone of western North America Stephen Arno The University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Arno, Stephen, "Interpreting the timberline: An aid to help park naturalists to acquaint visitors with the subalpine-alpine ecotone of western North America" (1966). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 6617. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/6617 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INTEKFRETING THE TIMBERLINE: An Aid to Help Park Naturalists to Acquaint Visitors with the Subalpine-Alpine Ecotone of Western North America By Stephen F. Arno B. S. in Forest Management, Washington State University, 196$ Presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Forestry UNIVERSITY OF MONTANA 1966 Approved by: Chairman, Board of Examiners bean. Graduate School Date Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. UMI Number: EP37418 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. -

Alpine Ecosystems

TWENTY-NINE Alpine Ecosystems PHILIP W. RUNDEL and CONSTANCE I. MILLAR Introduction Alpine ecosystems comprise some of the most intriguing hab writing about the alpine meadows of the Sierra Nevada, felt itats of the world for the stark beauty of their landscapes and his words were inadequate to describe “the exquisite beauty for the extremes of the physical environment that their resi of these mountain carpets as they lie smoothly outspread in dent biota must survive. These habitats lie above the upper the savage wilderness” (Muir 1894). limit of tree growth but seasonally present spectacular flo ral shows of low-growing herbaceous perennial plants. Glob ally, alpine ecosystems cover only about 3% of the world’s Defining Alpine Ecosystems land area (Körner 2003). Their biomass is low compared to shrublands and woodlands, giving these ecosystems only a Alpine ecosystems are classically defined as those communi minor role in global biogeochemical cycling. Moreover, spe ties occurring above the elevation of treeline. However, defin cies diversity and local endemism of alpine ecosystems is rela ing the characteristics that unambiguously characterize an tively low. However, alpine areas are critical regions for influ alpine ecosystem is problematic. Defining alpine ecosystems encing hydrologic flow to lowland areas from snowmelt. based on presence of alpine-like communities of herbaceous The alpine ecosystems of California present a special perennials is common but subject to interpretation because case among alpine regions of the world. Unlike most alpine such communities may occur well below treeline, while other regions, including the American Rocky Mountains and the areas well above treeline may support dense shrub or matted European Alps (where most research on alpine ecology has tree cover. -

BRIGHAM YOUNG UNIVERSITY GEOLOGY STUDIES Volume 42, Part I, 1997

BRIGHAM YOUNG UNIVERSITY GEOLOGICAL SOCIETY OF AMERICA FIELD TRIP GUIDE BOOK 1997 ANNUAL MEETING SALT LAKE CITY, UTAH PAR' EDITED BY PAUL KARL LINK AND BART J. KOWALLIS VOIUME 42 I997 PROTEROZOIC TO RECENT STRATIGRAPHY, TECTONICS, AND VOLCANOLOGY, UTAH, NEVADA, SOUTHERN IDAHO AND CENTRAL MEXICO Edited by Paul Karl Link and Bart J. Kowallis BRIGHAM YOUNG UNIVERSITY GEOLOGY STUDIES Volume 42, Part I, 1997 CONTENTS Neoproterozoic Sedimentation and Tectonics in West-Central Utah ..................Nicholas Christie-Blick 1 Proterozoic Tidal, Glacial, and Fluvial Sedimentation in Big Cottonwood Canyon, Utah ........Todd A. Ehlers, Marjorie A. Chan, and Paul Karl Link 31 Sequence Stratigraphy and Paleoecology of the Middle Cambrian Spence Shale in Northern Utah and Southern Idaho ............... W. David Liddell, Scott H. Wright, and Carlton E. Brett 59 Late Ordovician Mass Extinction: Sedimentologic, Cyclostratigraphic, and Biostratigraphic Records from Platform and Basin Successions, Central Nevada ............Stan C. Finney, John D. Cooper, and William B. N. Beny 79 Carbonate Sequences and Fossil Communities from the Upper Ordovician-Lower Silurian of the Eastern Great Basin .............................. Mark T. Harris and Peter M. Sheehan 105 Late Devonian Alamo Impact Event, Global Kellwasser Events, and Major Eustatic Events, Eastern Great Basin, Nevada and Utah .......................... Charles A. Sandberg, Jared R. Morrow and John E. Warme 129 Overview of Mississippian Depositional and Paleotectonic History of the Antler Foreland, Eastern Nevada and Western Utah ......................................... N. J. Silberling, K. M. Nichols, J. H. Trexler, Jr., E W. Jewel1 and R. A. Crosbie 161 Triassic-Jurassic Tectonism and Magmatism in the Mesozoic Continental Arc of Nevada: Classic Relations and New Developments ..........................S. J. -

The White Mountains Traverse Trip Notes

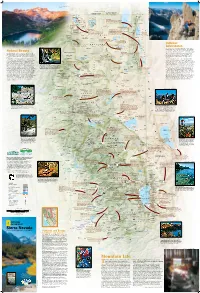

The White Mountains Traverse Trip Notes The White Mountains Crest Hike This is one of the most amazing hikes of its length in the country. This is also a rugged cross country trip, trailless except for a couple of miles on a closed road and it takes place at elevations above 11,000' for more than 95% of the distance. The White Mountains are the first of the Great Basin desert ranges and rise to over fourteen thousand feet on the east side of the Owens Valley. The Whites are home to some of the oldest known living things, the bristlecone pine, which can live for over four thousand years. For a while White Mountain was rumored to be higher than Mt. Whitney -it is not, but is a mere 250 feet lower and is perhaps the "easiest" fourteener in California. The Whites are remote, little traveled and true wilderness and the 2009 designation of them as a Wilderness area recognized these values. We hope that you will join us to explore this area with its fantastic views of the whole Sierra Nevada range from Olancha to the Tahoe area. Golden eagles, mountain lions, and groups of desert bighorn sheep are amongst the wildlife here and we hope to be lucky enough to see them. Itinerary Camp elevations are high (higher generally than those in the Sierra Nevada) on this trip so it is essential that you get at least one night and preferably three nights sleeping at 9,000' or higher prior to this trip. Day 1: We will meet at the Sierra Mountain Center office for the pre trip meeting. -

Sierra Nevada’S Endless Landforms Are Playgrounds for to Admire the Clear Fragile Shards

SIERRA BUTTES AND LOWER SARDINE LAKE RICH REID Longitude West 121° of Greenwich FREMONT-WINEMA OREGON NATIONAL FOREST S JOSH MILLER PHOTOGRAPHY E E Renner Lake 42° Hatfield 42° Kalina 139 Mt. Bidwell N K WWII VALOR Los 8290 ft IN THE PACIFIC ETulelake K t 2527 m Carr Butte 5482 ft . N.M. N. r B E E 1671 m F i Dalton C d Tuber k Goose Obsidian Mines w . w Cow Head o I CLIMBING THE NORTHEAST RIDGE OF BEAR CREEK SPIRE E Will Visit any of four obsidian mines—Pink Lady, Lassen e Tule Homestead E l Lake Stronghold l Creek Rainbow, Obsidian Needles, and Middle Fork Lake Lake TULE LAKE C ENewell Clear Lake Davis Creek—and take in the startling colors and r shapes of this dense, glass-like lava rock. With the . NATIONAL WILDLIFE ECopic Reservoir L proper permit you can even excavate some yourself. a A EM CLEAR LAKE s EFort Bidwell REFUGE E IG s Liskey R NATIONAL WILDLIFE e A n N Y T REFUGE C A E T r W MODOC R K . Y A B Kandra I Blue Mt. 5750 ft L B T Y S 1753 m Emigrant Trails Scenic Byway R NATIONAL o S T C l LAVA E Lava ows, canyons, farmland, and N E e Y Cornell U N s A vestiges of routes trod by early O FOREST BEDS I W C C C Y S B settlers and gold miners. 5582 ft r B K WILDERNESS Y . C C W 1701 m Surprise Valley Hot Springs I Double Head Mt. -

Edward Stuhl Papers MSS 150

Edward Stuhl Papers MSS 150 Special Collections• Meriam Library •California State University, Chico Contact Information Special Collections Meriam Library California State University, Chico Chico, CA 95929-0295 Phone: 530.898.6342 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.csuchico.edu/lbib/spc/iepages/home.html Collection Summary Title Edward Stuhl Papers, 1901-1981 Call Number MSS 150 Creator Stuhl, Edward, 1887-1984. Language of Materials English Extent Items: 31 boxes Linear Feet: 14.4 Abstract Diaries and journals of Edward Stuhl. Also includes correspondences, clippings, photographs, maps, water color paintings. Most of material relates to mountain climbing in California, Oregon, Washington, and Mexico. Four boxes contain material about Mount Shasta. Information for Researchers Access Restrictions Collection is open for research without restriction. MSS 150 23 August 2016 1 Usage Restrictions No restrictions. Digital Access http://archives.csuchico.edu/cdm/landingpage/collection/coll40 http://archives.csuchico.edu/cdm/landingpage/collection/coll5 Publication Rights The library can only claim physical ownership of the collection. Users are responsible for satisfying any claimants of literary property. Alternate Form of Material No alternative forms available. Acquisition Information Lare Tanner, gift 1988 Processing Information Processed by: Mary Ellen Bailey, 1999, Pamela Nett Kruger, June 1, 2012 Encoded by: Preferred Citation Edward Stuhl Papers, MSS 150, Special Collections, Meriam Library, California State University, Chico. Online Catalog Headings These and related materials may be found under the following headings in online catalogs. Stuhl, Edward, 1887-1984. Mountaineering. Mountains -- California. Mountains -- Oregon. Mountains -- Washington. White Mountains (Calif. and Nev.) Thompson Peak (Calif.) Eddy, Mount (Calif.) Preston Peak (Calif.) Linn, Mount (Calif.) Whitney, Mount (Calif.) Lola, Mount (Calif.) Rose, Mount (Calif.) Devils Postpile National Monument (Calif.) Walker Pass.