Final Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Annual Report

Christian Schools Sports Association Annual Report Executive Officers Report 26 years ago on the 28 September 1988 the Christian Schools Sports Association was formed and became an incorporated body. Many of our founding Principals have retired in the past few years leaving the responsibility of upholding & maintaining their vision to foster Christian thought and practice through sporting events within and between schools with you and me. Many outside the Associations may ask “Why have a Christian Sports Association?” The motto of Covenant Christian School is "All Knowledge through Christ". They state: …..The Christian believes that there are no neutral facts, that everything is related to God and has significance beyond this life. ... Christian education involves every subject of knowledge.. ... Christian education requires a Christian point of view for the whole curriculum; a God-centred program in every department ... A Christian School seeks to be Christian every hour of the school day. www.covenant.nsw.edu.au/why-christian-school.html As sports teachers and coaches we have a unique relationship with our students. We have the opportunity to share our faith with them and show them what it means to be a Christian both on and off the sporting field. By doing this we are not only proclaiming the Kingdom of God but bringing glory & honour to our Lord Jesus Christ. A former coach from Washington Redskins “Vince Lombardi” was famous for his statement: “Winning isn’t the most important thing: it is the only thing” Shortly before Vince Lombardi died he declared: “I wish I’d never said it. -

Inaburra School Annual Report 2017 Contents

INABURRAFAITH KNOWLEDGE LOVE INABURRA SCHOOL ANNUAL REPORT 2017 CONTENTS THEME ONE A message from key school bodies 2-4 THEME TWO Contextual information about the school and characteristics of the student body 6 THEME THREE Student outcomes in standardized national literacy and numeracy testing 8 THEME FOUR Senior secondary outcomes (student achievement) 10 THEME FIVE Teacher qualifications and professional learning 12 THEME SIX Workforce composition 13 THEME SEVEN Student attendance and retention rates and post-school destinations in secondary schools 14 THEME EIGHT Enrolment policies 15 Guidelines for Enrolment at Inaburra School 16-19 THEME NINE Other school policies 20 THEME TEN School determined priority areas for improvement 22 THEME ELEVEN Initiatives promoting respect and responsibility 24 THEME TWELVE Parent, student and teacher satisfaction 25-26 THEME THIRTEEN Summary financial information 28 B What I value about Inaburra - A safe and caring environment where my children are encouraged and supported to grow as individuals while being caring and respectful to Inaburra Parent others. 1 THEME ONE A MESSAGE FROM KEY SCHOOL BODIES Inaburra is a significant project Mr Tim Bowden tendered his resignation as Principal of Inaburra of Menai Baptist Church (MBC). School, with effect from the end of the 2017 school year as a Together with Inaburra Preschool, consequence of being offered and accepting the Headmastership MBC seeks to minister to the of Trinity Grammar School from the beginning of 2018. A number local community in a relevant of leaving events, with the school community, were held in the final and practical way. Inaburra is a term to celebrate Tim’s seven years at Inaburra and his significant learning community and not just contribution and godly leadership over that time. -

July 29, 2019 Key Week 2 CIS Primary Golf Paper Selection Date

NSW Combined Independent Schools Newsletter No.22 – July 29, 2019 Key Primary Nomination Event Secondary Nomination PSSA Events Meetings Primary Trial/Championship Secondary Trial/Championship All Schools Events Other Events Week 2 CIS Primary Golf Paper Selection Date only Mon 29 Jul 2019 NSWPSSA Netball Championships (W) Tue 30 Jul 2019 - Thu 01 Aug 2019 CIS Primary Girls Softball Nominations Close Wed 31 Jul 2019 CIS AGM & Board Meeting 3 Wed 31 Jul 2019 NSW All Schools 15 Years & Under Touch Football Championships Sat 03 Aug 2019 - Sun 04 Aug 2019 Week 3 CIS 15 Years & Under and Open Netball Challenge Day Mon 05 Aug 2019 Association Team Entries Due CIS Management Meeting 3 Tue 06 Aug 2019 CIS Primary Girls Cricket Nominations Close Wed 07 Aug 2019 CIS Primary Girls Softball Trials Wed 07 Aug 2019 NSWPSSA Athletics Selection Trial Thu 08 Aug 2019 CIS Nomination Guidelines - General 1. CIS does not accept Late Nominations. 2. Nominations will only be accepted online from NSWCISSC Member Schools or Member Associations 3. Once a student or teacher has been registered with CIS any subsequent sport nomination will be a renewal rather than a registration. 4. As a nominating teacher or association please ensure the students name, and date of birth have been entered correctly and the Parent/Guardian email is correct and frequently used. The system will send an email to the parent to enable them to complete the registration /renewal process. 5. A sport nomination fee of $25.03 will be charged for all sports in 2019 except for triathlon. -

Child Protection Policy 2013

C NSW COMBINED INDEPENDENT SCHOOLS SPORTS COUNCIL (CIS) CHILD PROTECTION POLICY INTENDED USE This Policy document is intended to be provided and made available to staff including employees, workers, volunteers, agents and/or contractors during their employment or engagement with CIS to ensure a clear understanding of their duties and obligations under the key items of child protection legislation in NSW. This Policy outlines the key concepts and definitions under the relevant legislation including mandatory reporters, reportable conduct, and risk management. It also sets out expected standards of behaviour in relation to employees, workers, volunteers, agents and/or contractors and their relationships with students. DEFINITIONS CIS worker means for the Purposes of this Child Protection Policy, all CIS employees whether full-time, part-time, temporary or casual, and all member school employees appointed as CIS convenors, coaches, managers or officials and all other CIS volunteers or contractors. CEO means the current Chief Executive Officer of CIS. CIS events means any sporting activities, events and/or competitions organised and/or operated by CIS. Member Schools – Members schools are the schools affiliated to CIS who participate in the sporting activities run by CIS. Refer to Attachment A for a full list of CIS member schools. INTRODUCTION 1.1. General The safety, protection and well-being of all students is of fundamental importance to CIS. CIS and CIS workers have a range of different obligations relating to the safety, protection and welfare of students including: a) a duty of care to ensure that reasonable steps are taken to prevent harm to students; b) obligations under child protection legislation; and c) obligations under work health and safety legislation. -

Answers to Questions on Notice

QoN E60_08 Funding of Schools 2001 - 2007 ClientId Name of School Location State Postcode Sector year Capital Establishment IOSP Chaplaincy Drought Assistance Flagpole Country Areas Parliamentary Grants Grants Program Measure Funding Program and Civics Education Rebate 3 Corpus Christi School BELLERIVE TAS 7018 Catholic systemic 2002 $233,047 3 Corpus Christi School BELLERIVE TAS 7018 Catholic systemic 2006 $324,867 3 Corpus Christi School BELLERIVE TAS 7018 Catholic systemic 2007 $45,000 4 Fahan School SANDY BAY TAS 7005 independent 2001 $182,266 4 Fahan School SANDY BAY TAS 7005 independent 2002 $130,874 4 Fahan School SANDY BAY TAS 7005 independent 2003 $41,858 4 Fahan School SANDY BAY TAS 7005 independent 2006 $1,450 4 Fahan School SANDY BAY TAS 7005 independent 2007 $22,470 5 Geneva Christian College LATROBE TAS 7307 independent 2002 $118,141 5 Geneva Christian College LATROBE TAS 7307 independent 2003 $123,842 5 Geneva Christian College LATROBE TAS 7307 independent 2004 $38,117 5 Geneva Christian College LATROBE TAS 7307 independent 2005 $5,000 $2,825 5 Geneva Christian College LATROBE TAS 7307 independent 2007 $32,500 7 Holy Rosary School CLAREMONT TAS 7011 Catholic systemic 2005 $340,490 7 Holy Rosary School CLAREMONT TAS 7011 Catholic systemic 2007 $49,929 $1,190 9 Immaculate Heart of Mary School LENAH VALLEY TAS 7008 Catholic systemic 2006 $327,000 $37,500 10 John Calvin School LAUNCESTON TAS 7250 independent 2005 $41,083 10 John Calvin School LAUNCESTON TAS 7250 independent 2006 $44,917 $1,375 10 John Calvin School LAUNCESTON -

Top 50 Secondary Schools ‐ Overall

Top 50 Secondary Schools ‐ Overall This ranking is based on the schools average performance in years 7 and 9. The results in each area; reading, writing, spelling, grammar and punctuation, and numeracy are based on each school's average results in only year 9. School Suburb Rank James Ruse Agricultural High School Carlingford 1 North Sydney Girls High School Crows Nest 2 North Sydney Boys High School Crows Nest 3 Sydney Girls High School Surry Hills 4 Hornsby Girls High School Hornsby 5 St George Girls High School Kogarah 6 Baulkham Hills High School Baulkham Hills 7 SydneySydney BoBoysys HiHighgh School SurrSurryy Hills 8 Sydney Grammar School Darlinghurst 9 Girraween High School Girraween 10 Fort Street High School Petersham 11 Northern Beaches Secondary College Manly Campus North Curl Curl 12 Hurlstone Agricultural High School Glenfield 13 Normanhurst Boys High School Normanhurst 14 PenrithPenrith HighHigh SchoolSchool PenrithPenrith 15 Merewether High School Broadmeadow 16 Smiths Hill High School Wollongong 17 Sydney Technical High School Bexley 18 Caringbah High School Caringbah 19 Gosford High School Gosford 20 Conservatorium High School Sydney 21 St Aloysius' College Milsons Point 22 SCEGGS, Darlinghurst Darlinghurst 22 Abbotsleigh Wahroonga 23 Ascham School Ltd Edgecliff 24 Pymble Ladies' College Pymble 25 Ravenswood School for Girls Gordon 26 Meriden School Strathfield 27 MLC School Burwood 28 Presbyterian Ladies College Croydon 29 Sefton High School Sefton 30 Loreto Kirribilli Kirribilli 31 Queenwood School for Girls Ltd Mosman -

Download Brochure

Welcome home Imagine coming home to a spacious premium residence, set in an idyllic natural wonderland in the sought-after suburb of Barden Ridge in Sydney’s Sutherland Shire. 3 A BOUTIQUE SETTING FOR Aspirational living awaits at The Ridgeway where natural harmony blends with urban connection for an enviable lifestyle. The Ridgeway is a boutique land estate in the welcoming neighbourhood affectionately known as ‘The Ridge’. Create the lifestyle Your Dream Lifestyle that you always dreamed of as you exchange city bustle for harmonious living with an abundance of open green space and parklands. SYDNEY M5 CBD NEW ILLAWARRA BANGOR PRI N C ES ROAD CRONULLA MENAI BYPASS HIGHWAY MARKETPLACE THE RIDGE MENAI LUCAS HEIGHTS BARDEN RIDGE GOLF COURSE COMMUNITY SCHOOL OVAL ROYA L NATIONAL PARK WORONORA SHIRE CHRISTIAN RIVER SCHOOL 5 PERFECTLY DESIGNED FOR Aspirational Living With prime connectivity to the established amenity at neighbouring Menai, achieve a lifestyle of convenience and endless possibilities. Your growing or established family will blossom as you step up to aspirational living at The Ridgeway. Artist Impression 7 Live in a natural paradise with the pristine woodlands of the Heathcote National AN IDYLLIC COMMUNITY TO Park surrounding The Ridgeway. The sweeping green spaces of The Ridge Golf Course & Driving Range and the majestic Sydney Turpentine-Ironbark Forest are on your doorstep. Walk or cycle the meandering pathways of your leafy Welcome Home community with its bespoke native landscaping. Look forward to your very own neighbourhood -

Annual Report

Christian Schools Sports Association Annual Report Executive Officers Report As I start writing this report I am sitting at the CSSA Primary State Tennis GD watching the Yr 5/6 Boys finals. It is so encouraging to see the boys play with not only the determination to win but with a spirit of good sportsmanship, congratulating each other after a winning shot. The day began in prayer acknowledging God for all that He has done and thanking Him for the gifts and talents He has given us. It is such a privilege to be part of a school system where we can be open about our faith in God and speak to our students about their relationship with Jesus. I would like to share the following story from Lisa Mallard at Northern Beaches CS which shows how blessed we are to be part of the Christian Schools Sports Association: The day before we played our 1st game in the Primary State Cricket KO Competition one of our Yr 5 boys passed away from a brain tumour. He was part of our team and was amazingly passionate about his cricket. The boys in the team only found out the night before the game and had to leave early the next day before they could meet with school counselors & the rest of their class mates. There were lots of tears and the boys wore arm bands for their friend. Their coach & the boys prayed together before the game and there was a real sense of looking after each other - our opponents Pacific Hills CS were so supportive. -

2013 – Issue 2

2013 – Issue 2 Journal of the Economics and Business Educators New South Wales Economics and Business Educators NSW Board of Directors PRESIDENT: Mr Joe Alvaro, Marist College North Shore VICE PRESIDENTS: Ms Kate Dally, Birrong Girls High School Mr Stuart Jones, Inaburra School TREASURER: Ms Bronwyn Hession, Board of Studies NSW and Business Educators Australasia Inc. (President) COMPANY SECRETARY: Ms Pauline Sheppard, Australian Islamic College DIRECTORS: Mr Andrew Athavle, William Carey Christian School Ms Cheryl Brennan, Illawarra Christian School Professor John Lodewijks, University of Western Sydney Ms Rhonda Thompson, Catholic Education Office – Southern Region EDITORS: Ms Kate Dally, Birrong Girls High School Professor John Lodewijks, University of Western Sydney DESKTOP PUBLISHING: Ms Jill Sillar, Professional Teachers’ Council NSW PUBLISHED BY: Economics & Business Educators NSW ABN 29 002 677 750 ISSN 1488-3696 3B Smalls Road, Ryde NSW 2112 Telephone: (02) 9886 7786 Fax: (02) 9886 7673 Email: [email protected] Website: www.ebe.nsw.edu.au “THE EBE JOURNAL” / “ECONOMICS” is indexed APAIS: Australian Public Affairs Information Service produced by the National Library of Australia in both online and CD-ROM format. Access to APAIS is now available via database subscription from: RMIT Publishing / INFORMIT – PO Box 12058 A’Beckett Street, Melbourne 8006; Tel. (03) 9925 8100; http://www.rmitpublishing.com.au; email: [email protected]. The phone for APAIS information is (02) 625 1650; the phone for printed APAIS is (02) 625 1560. Information about APAIS is also available via the National Library website at: http//www.nla.gov.au/apais/index.html The ISSN assigned to The EBE Journal is 1834-1780. -

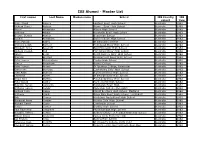

ISS Alumni - Master List

ISS Alumni - Master List First names Last Name Maiden name School ISS Country ISS cohort Year Brian David Aarons Fairfield Boys' High School Australia 1962 Richard Daniel Aldous Narwee Boys' High School Australia 1962 Alison Alexander Albury High School Australia 1962 Anthony Atkins Hurstville Boys' High School Australia 1962 George Dennis Austen Bega High School Australia 1962 Ronald Avedikian Enmore Boys' High School Australia 1962 Brian Patrick Bailey St Edmund's College Australia 1962 Anthony Leigh Barnett Homebush Boys' High School Australia 1962 Elizabeth Anne Beecroft East Hills Girls' High School Australia 1962 Richard Joseph Bell Fort Street Boys' High School Australia 1962 Valerie Beral North Sydney Girls' High School Australia 1962 Malcolm Binsted Normanhurst Boys' High School Australia 1962 Peter James Birmingham Casino High School Australia 1962 James Bradshaw Barker College Australia 1962 Peter Joseph Brown St Ignatius College, Riverview Australia 1962 Gwenneth Burrows Canterbury Girls' High School Australia 1962 John Allan Bushell Richmond River High School Australia 1962 Christina Butler St George Girls' High School Australia 1962 Bruce Noel Butters Punchbowl Boys' High School Australia 1962 Peter David Calder Hunter's Hill High School Australia 1962 Malcolm James Cameron Balgowlah Boys' High Australia 1962 Anthony James Candy Marcellan College, Randwich Australia 1962 Richard John Casey Marist Brothers High School, Maitland Australia 1962 Anthony Ciardi Ibrox Park Boys' High School, Leichhardt Australia 1962 Bob Clunas -

Innovative-Schools-2016-Report

EDUCATORONLINE.COM.AU ISSUE 2.3 THE BIG INTERVIEW Graham Eather, Callaghan College LEGAL INSIGHT Your ‘duty of care’ obligations explained BRINGING SCHOOL BRANDS ALIVE How to engage sta , students and the community INNOVATIVE SCHOOLS The change merchants shaping tomorrow’s leaders Special Report: Master of Education Guide 2016 00_OFC_SUBBED.indd 2 19/08/2016 1:48:39 PM COVER STORY INNOVATIVE SCHOOLS 2016 THE CHANGE MERCHANTS In our second annual Innovative Schools list, The Educator once again profiles the schools leading the charge in transforming Australia’s educational framework 20 www.educatoronline.com.au Sponsored by SCHOOL INDEX NAME PAGE STATE TYPE Aitkenvale Public School 22 QLD P All Hallows School 31 QLD I Aspect Hunter School 22 NSW P Bendigo South East College 22 VIC P Bethania Lutheran School 24 QLD I Brighton Secondary School 35 SA P Callaghan College 32 NSW I Catholic Regional College, Sydenham 23 VIC C East Hills Girls Technology High School 23 NSW P WELCOME TO The Educator’s second shortlist, but we’re now proud to be Giant Steps 25 NSW P annual Innovative Schools list. able to highlight the work of 40 schools Grace Lutheran College 30 QLD I Following the exceptional response we whose endeavours deserve special Hale School 28 WA I received to our request for submissions for recognition. Over the following pages, Hastings Secondary College 35 NSW P our inaugural list, we were overwhelmed we recognise these exceptional schools, Humpybong State School 22 QLD P again this year by the number of entries with 12 of them being spotlighted in from schools right across the country, greater detail. -

Inaburra School Annual Report 2016

INABURRAFAITH KNOWLEDGE LOVE INABURRA SCHOOL ANNUAL REPORT 2016 A Project of Menai Baptists CONTENTS THEME ONE A message from key school bodies 2-4 THEME TWO Contextual information about the school and characteristics of the student body 6 THEME THREE Student outcomes in standardized national literacy and numeracy testing 8 THEME FOUR Senior secondary outcomes (student achievement) 10 THEME FIVE Teacher qualifications and professional learning 12 THEME SIX Workforce composition 13 THEME SEVEN Student attendance and retention rates and post-school destinations in secondary schools 14 THEME EIGHT Enrolment policies 15 Guidelines for Enrolment at Inaburra School 16-19 THEME NINE Other school policies 20 THEME TEN School determined priority areas for improvement 22 THEME ELEVEN Initiatives promoting respect and responsibility 24 THEME TWELVE Parent, student and teacher satisfaction 25-26 THEME THIRTEEN Summary financial information 28 B What I value about Inaburra - Knowing that my son has been valued as a person. It has been nice to be complimented on my son’s manner in which he conducts himself. I have been very proud to say that my son was at Inaburra. Inaburra Parent 1 THEME ONE A MESSAGE FROM KEY SCHOOL BODIES The School remains a significant This year has seen a substantial building project undertaken, which ministry of Menai Baptist Church includes: (MBC). Together with the Inaburra • More playground space for the Junior School through the Preschool, MBC seeks to work hand removal of the demountable classrooms. in hand with the local community. • The establishment of a new Learning Commons for K-12 At Inaburra, we see ourselves as a students, supplementing the existing libraries.