An Edition of Selected Orchestral Works of Sir John Blackwood Mcewen (1868 - 1948)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

University of Florida Thesis Or Dissertation Formatting

IRISH MUSIC AND HOME-RULE POLITICS, 1800-1922 By AARON C. KEEBAUGH A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2011 1 © 2011 Aaron C. Keebaugh 2 ―I received a letter from the American Quarter Horse Association saying that I was the only member on their list who actually doesn‘t own a horse.‖—Jim Logg to Ernest the Sincere from Love Never Dies in Punxsutawney To James E. Schoenfelder 3 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS A project such as this one could easily go on forever. That said, I wish to thank many people for their assistance and support during the four years it took to complete this dissertation. First, I thank the members of my committee—Dr. Larry Crook, Dr. Paul Richards, Dr. Joyce Davis, and Dr. Jessica Harland-Jacobs—for their comments and pointers on the written draft of this work. I especially thank my committee chair, Dr. David Z. Kushner, for his guidance and friendship during my graduate studies at the University of Florida the past decade. I have learned much from the fine example he embodies as a scholar and teacher for his students in the musicology program. I also thank the University of Florida Center for European Studies and Office of Research, both of which provided funding for my travel to London to conduct research at the British Library. I owe gratitude to the staff at the Library of Congress in Washington, D.C. for their assistance in locating some of the materials in the Victor Herbert Collection. -

Download Booklet

557439bk Bax US 2/07/2004 11:02am Page 5 in mind some sort of water nymph of Greek vignette In a Vodka Shop, dated 22nd January 1915. It Ashley Wass mythological times.’ In a newspaper interview Bax illustrates, however, Bax’s problem trying to keep his himself described it as ‘nothing but tone colour – rival lady piano-champions happy, for Myra Hess gave The young British pianist, Ashley Wass, is recognised as one of the rising stars BAX changing effects of tone’. the first performance at London’s Grafton Galleries on of his generation. Only the second British pianist in twenty years to reach the In January 1915, at a tea party at the Corders, the 29th April 1915, and as a consequence the printed finals of the Leeds Piano Competition (in 2000), he was the first British pianist nineteen-year-old Harriet Cohen appeared wearing as a score bears a dedication to her. ever to win the top prize at the World Piano Competition in 1997. He appeared Piano Sonatas Nos. 1 and 2 decoration a single daffodil, and Bax wrote almost in the ‘Rising Stars’ series at the 2001 Ravinia Festival and his promise has overnight the piano piece To a Maiden with a Daffodil; been further acknowledged by the BBC, who selected him to be a New he was smitten! Over the next week two more pieces Generations Artist over two seasons. Ashley Wass studied at Chethams Music Dream in Exile • Nereid for her followed, the last being the pastiche Russian Lewis Foreman © 2004 School and won a scholarship to the Royal Academy of Music to study with Christopher Elton and Hamish Milne. -

Download Booklet

557592 bk Bax UK/US 8/03/2005 02:22pm Page 5 Ashley Wass Also available: The young British pianist, Ashley Wass, is recognised as one of the rising stars of his generation. Only the second British pianist in twenty years to reach the finals of the Leeds Piano Competition (in 2000), he was the first British BAX pianist ever to win the top prize at the World Piano Competition in 1997. He appeared in the ‘Rising Stars’ series at the 2001 Ravinia Festival and his promise has been further acknowledged by the BBC, who selected him to be a New Generations Artist over two seasons. Ashley Wass studied at Chethams Music School and won a scholarship to the Royal Academy of Music to study with Christopher Elton and Hamish Milne. He was made an Associate of the Piano Sonatas Nos. 3 and 4 Royal Academy in 2002. In 2000/1 he was a participant at the Marlboro Music Festival, playing chamber music with musicians such as Mitsuko Uchida, Richard Goode and David Soyer. He has given recitals at most of the major British concert halls including the Wigmore Hall, Queen Elizabeth Hall, Purcell Room, Bridgewater Hall and St Water Music • Winter Waters David’s Hall. His concerto performances have included Beethoven and Brahms with the Philharmonia, Mendelssohn with the Orchestre National de Lille and Mozart with the Vienna Chamber Orchestra at the Vienna Konzerthaus and the Brucknerhaus in Linz. He has also worked with Sir Simon Rattle and the City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra, the London Mozart Players, the BBC Scottish Symphony Orchestra and the BBC Ashley Wass Philharmonic. -

British and Commonwealth Concertos from the Nineteenth Century to the Present

BRITISH AND COMMONWEALTH CONCERTOS FROM THE NINETEENTH CENTURY TO THE PRESENT A Discography of CDs & LPs Prepared by Michael Herman Composers I-P JOHN IRELAND (1879-1962) Born in Bowdon, Cheshire. He studied at the Royal College of Music with Stanford and simultaneously worked as a professional organist. He continued his career as an organist after graduation and also held a teaching position at the Royal College. Being also an excellent pianist he composed a lot of solo works for this instrument but in addition to the Piano Concerto he is best known for his for his orchestral pieces, especially the London Overture, and several choral works. Piano Concerto in E flat major (1930) Mark Bebbington (piano)/David Curti/Orchestra of the Swan ( + Bax: Piano Concertino) SOMM 093 (2009) Colin Horsley (piano)/Basil Cameron/Royal Philharmonic Orchestra EMI BRITISH COMPOSERS 352279-2 (2 CDs) (2006) (original LP release: HMV CLP1182) (1958) Eileen Joyce (piano)/Sir Adrian Boult/London Philharmonic Orchestra (rec. 1949) ( + The Forgotten Rite and These Things Shall Be) LONDON PHILHARMONIC ORCHESTRA LPO 0041 (2009) Eileen Joyce (piano)/Leslie Heward/Hallé Orchestra (rec. 1942) ( + Moeran: Symphony in G minor) DUTTON LABORATORIES CDBP 9807 (2011) (original LP release: HMV TREASURY EM290462-3 {2 LPs}) (1985) Piers Lane (piano)/David Lloyd-Jones/Ulster Orchestra ( + Legend and Delius: Piano Concerto) HYPERION CDA67296 (2006) John Lenehan (piano)/John Wilson/Royal Liverpool Philharmonic Orchestra ( + Legend, First Rhapsody, Pastoral, Indian Summer, A Sea Idyll and Three Dances) NAXOS 8572598 (2011) MusicWeb International Updated: August 2020 British & Commonwealth Concertos I-P Eric Parkin (piano)/Sir Adrian Boult/London Philharmonic Orchestra ( + These Things Shall Be, Legend, Satyricon Overture and 2 Symphonic Studies) LYRITA SRCD.241 (2007) (original LP release: LYRITA SRCS.36 (1968) Eric Parkin (piano)/Bryden Thomson/London Philharmonic Orchestra ( + Legend and Mai-Dun) CHANDOS CHAN 8461 (1986) Kathryn Stott (piano)/Sir Andrew Davis/BBC Symphony Orchestra (rec. -

July 1934) James Francis Cooke

Gardner-Webb University Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University The tudeE Magazine: 1883-1957 John R. Dover Memorial Library 7-1-1934 Volume 52, Number 07 (July 1934) James Francis Cooke Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.gardner-webb.edu/etude Part of the Composition Commons, Ethnomusicology Commons, Fine Arts Commons, History Commons, Liturgy and Worship Commons, Music Education Commons, Musicology Commons, Music Pedagogy Commons, Music Performance Commons, Music Practice Commons, and the Music Theory Commons Recommended Citation Cooke, James Francis. "Volume 52, Number 07 (July 1934)." , (1934). https://digitalcommons.gardner-webb.edu/etude/824 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the John R. Dover Memorial Library at Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University. It has been accepted for inclusion in The tudeE Magazine: 1883-1957 by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE ETUDE * <Music *%Cagazine PADEREWSKI July 1934 Price 25 Cents n WHERE SHALL I GO Information for Etude Readers & Advertisers TO STUDY? THE ETUDE MUSIC MAGAZINE THE ETUDE Founded by Theodore Presser, 1883 The Etude Music Magazine “Music for Everybody” tJXCusic <^J)(Cagazine Private Teachers THEODORE PRESSER (Eastern) Philadelphia, Pa. Copyright, ISS4. by Theodore Presser Co. for U. S. A. and Oreca Britain Entered as second-class matter January lfi 1 II // WILLIAM C. CARL, Dir. 1884, at the P. 0. at Phila., Pa f^n- ’ A MONTHLY JOURNAL FOR THE MUSICIAN, THE MUSIC STUDENT AND ALL MUSIC LOVERS der the Act of March 3, 1879. Copy- Guilmant Organ School 51 FIFTH AVENUE, NEW YORK VOLUME LII. -

Contents Price Code an Introduction to Chandos

CONTENTS AN INTRODUCTION TO CHANDOS RECORDS An Introduction to Chandos Records ... ...2 Harpsichord ... ......................................................... .269 A-Z CD listing by composer ... .5 Guitar ... ..........................................................................271 Chandos Records was founded in 1979 and quickly established itself as one of the world’s leading independent classical labels. The company records all over Collections: Woodwind ... ............................................................ .273 the world and markets its recordings from offices and studios in Colchester, Military ... ...208 Violin ... ...........................................................................277 England. It is distributed worldwide to over forty countries as well as online from Brass ... ..212 Christmas... ........................................................ ..279 its own website and other online suppliers. Concert Band... ..229 Light Music... ..................................................... ...281 Opera in English ... ...231 Various Popular Light... ......................................... ..283 The company has championed rare and neglected repertoire, filling in many Orchestral ... .239 Compilations ... ...................................................... ...287 gaps in the record catalogues. Initially focussing on British composers (Alwyn, Bax, Bliss, Dyson, Moeran, Rubbra et al.), it subsequently embraced a much Chamber ... ...245 Conductor Index ... ............................................... .296 -

Tocc0262notes.Pdf

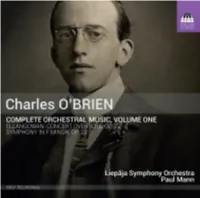

CHARLES O’BRIEN: A SCOTTISH ROMANTIC REDISCOVERED by John Purser Charles O’Brien was born in 1882 in Eastbourne, where his parents, normally based in Edinburgh, were staying for the summer season. His father, Frederick Edward Fitzgerald O’Brien, had worked as a trombonist in the first orchestra to be established in Eastbourne and there, in 1881, he had met and married Elise Ware. They would return there now and again, perhaps to visit her family, whose roots were in France: Elise’s grandfather had been a Girondin who had plotted against Robespierre and, in the words of Charles O’Brien’s son, Sir Frederick,1 ‘had to choose between exile and the guillotine. He chose the former and escaped to England, hence the Eastbourne connection’.2 Elise died tragically in 1919, after being struck by an army vehicle. As well as the trombone, Frederick Edward O’Brien played violin and viola and attempted, unsuccessfully, to teach his grandchildren the violin: ‘it was like snakes and ladders – one minor mistake and we had to start at the beginning again’, Sir Frederick recalled.3 Music went further back in the family than Charles’ father. His grandfather, Charles James O’Brien (1821–76) was also a composer and played the French horn, and his great-grandfather, Cornelius O’Brien (1775 or 1776–1867), who was born in Cork, was principal horn at Covent Garden. Charles O’Brien’s musical education was of the best. One of his early teachers was Thomas Henry Collinson (1858–1928) – father of the Francis Collinson who wrote The Traditional and National Music of Scotland.4 The elder Collinson was organist at St Mary’s Cathedral, Edinburgh, as well as conductor of the Edinburgh Choral Union, in which he was succeeded by O’Brien himself. -

Nonatonic Harmonic Structures in Symphonies by Ralph Vaughan Williams and Arnold Bax Cameron Logan [email protected]

University of Connecticut OpenCommons@UConn Doctoral Dissertations University of Connecticut Graduate School 12-2-2014 Nonatonic Harmonic Structures in Symphonies by Ralph Vaughan Williams and Arnold Bax Cameron Logan [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://opencommons.uconn.edu/dissertations Recommended Citation Logan, Cameron, "Nonatonic Harmonic Structures in Symphonies by Ralph Vaughan Williams and Arnold Bax" (2014). Doctoral Dissertations. 603. https://opencommons.uconn.edu/dissertations/603 i Nonatonic Harmonic Structures in Symphonies by Ralph Vaughan Williams and Arnold Bax Cameron Logan, Ph.D. University of Connecticut, 2014 This study explores the pitch structures of passages within certain works by Ralph Vaughan Williams and Arnold Bax. A methodology that employs the nonatonic collection (set class 9-12) facilitates new insights into the harmonic language of symphonies by these two composers. The nonatonic collection has received only limited attention in studies of neo-Riemannian operations and transformational theory. This study seeks to go further in exploring the nonatonic‟s potential in forming transformational networks, especially those involving familiar types of seventh chords. An analysis of the entirety of Vaughan Williams‟s Fourth Symphony serves as the exemplar for these theories, and reveals that the nonatonic collection acts as a connecting thread between seemingly disparate pitch elements throughout the work. Nonatonicism is also revealed to be a significant structuring element in passages from Vaughan Williams‟s Sixth Symphony and his Sinfonia Antartica. A review of the historical context of the symphony in Great Britain shows that the need to craft a work of intellectual depth, simultaneously original and traditional, weighed heavily on the minds of British symphonists in the early twentieth century. -

A MATTHAY Miscellany

A MATTHAY Miscellany Rare and unissued recordings by Tobias Matthay and his pupils Tobias Matthay ................ Columbia DX 444; matrices CAX 6582-1/83-1; recorded on 16 November 1932 MATTHAY Studies in the form of a Suite Op 16 1. No 1 Prelude ......................................................................................... (2.09) 2. No 8 Bravura ......................................................................................... (2.11) MATTHAY On Surrey Hills Op 30 3. No 1 Twilight Hills ................................................................................... (1.34) 4. No 4 Wind-Sprites .................................................................................... (1.56) Irene Scharrer SCHUMANN Piano Sonata No 2 in G minor Op 22 ........................ HMV (previously unissued) 5. I So rasch wie möglich ................................ matrices Cc 4295-1 and 4302-2; recorded on 4 March 1924 (4.47) 6. III Scherzo: Sehr rasch und markiert .................................................................. (1.33) 7. IV Rondo: Presto (beginning) ......................................................................... (2.14) 8. CHOPIN Prelude No 23 in F major Op 28 .............. HMV (previously unissued); matrix Cc 7096-3 [part] (0.54) recorded on 28 October 1925 9. SCHUBERT Impromptu in A flat major Op 90 No 4 (D899) ............... Columbia (previously unissued) (5.50) matrices WA 10248-2 and 10249; recorded on 12 May 1930 Raie Da Costa 10. VERDI/LISZT Rigoletto de Verdi – Paraphrase de Concert S434 .................. HMV C 1967 (6.37) matrices Cc 19809-1 and 19810-2; recorded on 13 June 1930 11. J STRAUSS II/GRÜNFELD Soirée de Vienne Op 56 ............ HMV B 3500; matrices Bb 19811-2 and 19812-1 (5.20) recorded on 13 June 1930 Ethel Bartlett 12. BACH/RUMMEL Beloved Jesus, we are here BWV731 .................... NGS 152; matrix WAX5311-1 (3.30) recorded on 23 December 1929 2 Denise Lassimonne BACH Two-Part Inventions BWV772–786 .............. -

Lionel Tertis, York Bowen, and the Rise of the Viola

THE VIOLA MUSIC OF YORK BOWEN: LIONEL TERTIS, YORK BOWEN, AND THE RISE OF THE VIOLA IN EARLY TWENTIETH-CENTURY ENGLAND A THESIS IN Musicology Presented to the Faculty of the University of Missouri-Kansas City in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree MASTER OF MUSIC by WILLIAM KENTON LANIER B.A., Thomas Edison State University, 2009 Kansas City, Missouri 2020 © 2020 WILLIAM KENTON LANIER ALL RIGHTS RESERVED THE VIOLA MUSIC OF YORK BOWEN: LIONEL TERTIS, YORK BOWEN, AND THE RISE OF THE VIOLA IN EARLY TWENTIETH-CENTURY ENGLAND William Kenton Lanier, Candidate for the Master of Music Degree in Musicology University of Missouri-Kansas City, 2020 ABSTRACT The viola owes its current reputation largely to the tireless efforts of Lionel Tertis (1876-1975), who, perhaps more than any other individual, brought the viola to light as a solo instrument. Prior to the twentieth century, numerous composers are known to have played the viola, and some even preferred it, but none possessed the drive or saw the necessity to establish it as an equal solo counterpart to the violin or cello. Likewise, no performer before Tertis had established themselves as a renowned exponent of the viola. Tertis made it his life’s work to bring the viola to the fore, and his musical prowess and technical ability on the instrument gave him the tools to succeed. Tertis was primarily a performer, thus collaboration with composers also comprised a necessary element of his viola crusade. He commissioned works from several British composers, including one of the first and most prolific composers for the viola, York Bowen (1884-1961). -

Musica Scotica

MUSICA SCOTICA 800 years of Scottish Music Proceedings from the 2005 and 2006 Conferences Edited by Heather Kelsall, Graham Hair & Kenneth Elliott Musica Scotica Trust Glasgow 2008 First published in 2008 by The Musica Scotica Trust c/o Dr Gordon Munro RSAMD 100 Renfrew Street Glasgow G2 3DB Scotland UK email: [email protected] website: www.musicascotica.org.uk Musica Scotica Editorial Board Dr. Kenneth Elliott, Glasgow University (General Editor) Dr. Gordon Munro, RSAMD (Assistant General Editor) Dr Stuart Campbell, Glasgow University Ms Celia Duffy, RSAMD Dr. Greta-Mary Hair, Edinburgh University Professor Graham Hair, Glasgow University Professor Alistair A. Macdonald, Gronigen University, Netherlands Dr. Margaret A. Mackay, Edinburgh University Dr. Kirsteen McCue, Glasgow University Dr. Elaine Moohan, The Open University Dr. Jane Mallinson, Glasgow University Dr. Moira Harris, Glasgow University Copyright © individual authors, 2005 and 2006 This book is copyright. Apart from fair dealing for the purposes of private study, research, criticism or review as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechaniscal, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior permission. Enquiries to be made to the publisher. Copying for Educational Purposes Where copies of part or the whole of the book are made under Section 53B or 53D of the Copyright Act 1968, the law requires that records of such copying be kept. In such cases, -

The Music of Sir Alexander Campbell Mackenzie (1847-1935): a Critical Study

The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. No quotation from it should be published without the written consent of the author and infomation derived from it should be acknowledged. The Music of Sir Alexander Campbell Mackenzie (1847-1935): A Critical Study Duncan James Barker A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Ph.D.) Music Department University of Durham 1999 Volume 2 of 2 23 AUG 1999 Contents Volume 2 Appendix 1: Biographical Timeline 246 Appendix 2: The Mackenzie Family Tree 257 Appendix 3: A Catalogue of Works 260 by Alexander Campbell Mackenzie List of Manuscript Sources 396 Bibliography 399 Appendix 1: Biographical Timeline Appendix 1: Biographical Timeline NOTE: The following timeline, detailing the main biographical events of Mackenzie's life, has been constructed from the composer's autobiography, A Musician's Narrative, and various interviews published during his lifetime. It has been verified with reference to information found in The Musical Times and other similar sources. Although not fully comprehensive, the timeline should provide the reader with a useful chronological survey of Mackenzie's career as a musician and composer. ABBREVIATIONS: ACM Alexander Campbell Mackenzie MT The Musical Times RAM Royal Academy of Music 1847 Born 22 August, 22 Nelson Street, Edinburgh. 1856 ACM travels to London with his father and the orchestra of the Theatre Royal, Edinburgh, and visits the Crystal Palace and the Thames Tunnel. 1857 Alexander Mackenzie admits to ill health and plans for ACM's education (July). ACM and his father travel to Germany in August: Edinburgh to Hamburg (by boat), then to Hildesheim (by rail) and Schwarzburg-Sondershausen (by Schnellpost).