Imidacloprid Does Not Enhance Growth and Yield of Muskmelon In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

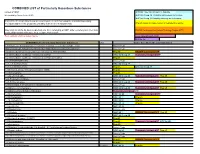

COMBINED LIST of Particularly Hazardous Substances

COMBINED LIST of Particularly Hazardous Substances revised 2/4/2021 IARC list 1 are Carcinogenic to humans list compiled by Hector Acuna, UCSB IARC list Group 2A Probably carcinogenic to humans IARC list Group 2B Possibly carcinogenic to humans If any of the chemicals listed below are used in your research then complete a Standard Operating Procedure (SOP) for the product as described in the Chemical Hygiene Plan. Prop 65 known to cause cancer or reproductive toxicity Material(s) not on the list does not preclude one from completing an SOP. Other extremely toxic chemicals KNOWN Carcinogens from National Toxicology Program (NTP) or other high hazards will require the development of an SOP. Red= added in 2020 or status change Reasonably Anticipated NTP EPA Haz list COMBINED LIST of Particularly Hazardous Substances CAS Source from where the material is listed. 6,9-Methano-2,4,3-benzodioxathiepin, 6,7,8,9,10,10- hexachloro-1,5,5a,6,9,9a-hexahydro-, 3-oxide Acutely Toxic Methanimidamide, N,N-dimethyl-N'-[2-methyl-4-[[(methylamino)carbonyl]oxy]phenyl]- Acutely Toxic 1-(2-Chloroethyl)-3-(4-methylcyclohexyl)-1-nitrosourea (Methyl-CCNU) Prop 65 KNOWN Carcinogens NTP 1-(2-Chloroethyl)-3-cyclohexyl-1-nitrosourea (CCNU) IARC list Group 2A Reasonably Anticipated NTP 1-(2-Chloroethyl)-3-cyclohexyl-1-nitrosourea (CCNU) (Lomustine) Prop 65 1-(o-Chlorophenyl)thiourea Acutely Toxic 1,1,1,2-Tetrachloroethane IARC list Group 2B 1,1,2,2-Tetrachloroethane Prop 65 IARC list Group 2B 1,1-Dichloro-2,2-bis(p -chloropheny)ethylene (DDE) Prop 65 1,1-Dichloroethane -

Impact of Imidacloprid and Horticultural Oil on Nonâ•Fitarget

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Masters Theses Graduate School 8-2007 Impact of Imidacloprid and Horticultural Oil on Non–target Phytophagous and Transient Canopy Insects Associated with Eastern Hemlock, Tsuga canadensis (L.) Carrieré, in the Southern Appalachians Carla Irene Dilling University of Tennessee - Knoxville Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes Part of the Entomology Commons Recommended Citation Dilling, Carla Irene, "Impact of Imidacloprid and Horticultural Oil on Non–target Phytophagous and Transient Canopy Insects Associated with Eastern Hemlock, Tsuga canadensis (L.) Carrieré, in the Southern Appalachians. " Master's Thesis, University of Tennessee, 2007. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes/120 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a thesis written by Carla Irene Dilling entitled "Impact of Imidacloprid and Horticultural Oil on Non–target Phytophagous and Transient Canopy Insects Associated with Eastern Hemlock, Tsuga canadensis (L.) Carrieré, in the Southern Appalachians." I have examined the final electronic copy of this thesis for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree of Master of Science, with a major in Entomology and Plant Pathology. Paris L. Lambdin, Major Professor We have read this thesis and recommend its acceptance: Jerome Grant, Nathan Sanders, James Rhea, Nicole Labbé Accepted for the Council: Carolyn R. -

Genetically Modified Baculoviruses for Pest

INSECT CONTROL BIOLOGICAL AND SYNTHETIC AGENTS This page intentionally left blank INSECT CONTROL BIOLOGICAL AND SYNTHETIC AGENTS EDITED BY LAWRENCE I. GILBERT SARJEET S. GILL Amsterdam • Boston • Heidelberg • London • New York • Oxford Paris • San Diego • San Francisco • Singapore • Sydney • Tokyo Academic Press is an imprint of Elsevier Academic Press, 32 Jamestown Road, London, NW1 7BU, UK 30 Corporate Drive, Suite 400, Burlington, MA 01803, USA 525 B Street, Suite 1800, San Diego, CA 92101-4495, USA ª 2010 Elsevier B.V. All rights reserved The chapters first appeared in Comprehensive Molecular Insect Science, edited by Lawrence I. Gilbert, Kostas Iatrou, and Sarjeet S. Gill (Elsevier, B.V. 2005). All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers. Permissions may be sought directly from Elsevier’s Rights Department in Oxford, UK: phone (þ44) 1865 843830, fax (þ44) 1865 853333, e-mail [email protected]. Requests may also be completed on-line via the homepage (http://www.elsevier.com/locate/permissions). Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Insect control : biological and synthetic agents / editors-in-chief: Lawrence I. Gilbert, Sarjeet S. Gill. – 1st ed. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-12-381449-4 (alk. paper) 1. Insect pests–Control. 2. Insecticides. I. Gilbert, Lawrence I. (Lawrence Irwin), 1929- II. Gill, Sarjeet S. SB931.I42 2010 632’.7–dc22 2010010547 A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library ISBN 978-0-12-381449-4 Cover Images: (Top Left) Important pest insect targeted by neonicotinoid insecticides: Sweet-potato whitefly, Bemisia tabaci; (Top Right) Control (bottom) and tebufenozide intoxicated by ingestion (top) larvae of the white tussock moth, from Chapter 4; (Bottom) Mode of action of Cry1A toxins, from Addendum A7. -

Large-Scale Field Trials of Imidacloprid for Control of The

PEST MANAGEMENT HORTSCIENCE 38(4):555–559. 2003. 5 mL/100 L (half-rate), were compared with endosulfan (350 g·L–1 a.i.) at the industry standard rate of 57 mL/100 L. The higher of Large-scale Field Trials of the two rates for imidacloprid corresponds to the discriminate dose (100% kill) of the Imidacloprid for Control of the insecticide against SCB (James and Nicholas, 2000). A water-only treatment was provided as Spined Citrus Bug control in all but one trial. Applications of the treatments were made with air-blast sprayers J. Mo1 and K. Philpot at a spray volume of 10 L/tree. Yanco Agricultural Institute, PMB Yanco, NSW 2703, Australia Trial-1 was conducted from 25 Oct. to 24 Nov. 2000 in Leeton. Lemon trees from three Additional index words. endosulfan withdrawal, alternative insecticide, beneficials, lemon, neighbouring citrus farms (separated by 1–2 Biprorulus bibax km) were used in this trial. The test trees were in six separate blocks (>100 m apart) containing Abstract. Four large-scale field trials were carried out in 2001 and 2002 in lemon or- from 60 to 453 trees. Fifteen plots of 60–100 chards in south-western New South Wales to assess the suitability of imidacloprid as a trees each were set up in the six lemon blocks. replacement for endosulfan in controlling the spined citrus bug (SCB), Biprorulus bibax Where more than one plot was set up in a Breddin (Hemiptera: Pentatomidae). The results showed that imidacloprid was at least single block, the boundaries were chosen in as effective as endosulfan in controlling SCB, even when it was applied at a rate cor- such a way that each plot contained a similar responding to half of its discriminate dose (100% kill). -

Proposed Interim Registration Review Decision for Imidacloprid

Docket Number EPA-HQ-OPP-2008-0844 www.regulations.gov Imidacloprid Proposed Interim Registration Review Decision Case Number 7605 January 2020 Approved by: Elissa Reaves, Ph.D. Acting Director Pesticide Re-evaluation Division Date: __ 1-22-2020 __ Docket Number EPA-HQ-OPP-2008-0844 www.regulations.gov Table of Contents I. INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................................. 4 A. Summary of Imidacloprid Registration Review............................................................... 5 B. Summary of Public Comments on the Draft Risk Assessments and Agency Responses 7 II. USE AND USAGE ............................................................................................................... 14 III. SCIENTIFIC ASSESSMENTS ......................................................................................... 15 A. Human Health Risks....................................................................................................... 15 1. Risk Summary and Characterization .......................................................................... 15 2. Human Incidents and Epidemiology .......................................................................... 17 3. Tolerances ................................................................................................................... 18 4. Human Health Data Needs ......................................................................................... 18 B. Ecological Risks ............................................................................................................ -

Pesticides and Toxic Substances

UNITED STATES ENVIRONMENTAL PROTECTION AGENCY WASHINGTON D.C., 20460 OFFICE OF PREVENTION, PESTICIDES AND TOXIC SUBSTANCES MEMORANDUM DATE: July 31, 2006 SUBJECT: Finalization of Interim Reregistration Eligibility Decisions (IREDs) and Interim Tolerance Reassessment and Risk Management Decisions (TREDs) for the Organophosphate Pesticides, and Completion of the Tolerance Reassessment and Reregistration Eligibility Process for the Organophosphate Pesticides FROM: Debra Edwards, Director Special Review and Reregistration Division Office of Pesticide Programs TO: Jim Jones, Director Office of Pesticide Programs As you know, EPA has completed its assessment of the cumulative risks from the organophosphate (OP) class of pesticides as required by the Food Quality Protection Act of 1996. In addition, the individual OPs have also been subject to review through the individual- chemical review process. The Agency’s review of individual OPs has resulted in the issuance of Interim Reregistration Eligibility Decisions (IREDs) for 22 OPs, interim Tolerance Reassessment and Risk Management Decisions (TREDs) for 8 OPs, and a Reregistration Eligibility Decision (RED) for one OP, malathion.1 These 31 OPs are listed in Appendix A. EPA has concluded, after completing its assessment of the cumulative risks associated with exposures to all of the OPs, that: (1) the pesticides covered by the IREDs that were pending the results of the OP cumulative assessment (listed in Attachment A) are indeed eligible for reregistration; and 1 Malathion is included in the OP cumulative assessment. However, the Agency has issued a RED for malathion, rather than an IRED, because the decision was signed on the same day as the completion of the OP cumulative assessment. -

Pests of the Flower Garden Phillip E

Pests of the Flower Garden Phillip E. Sloderbeck Entomologist Southwest Area Office This publication is meant to help ent names. One of the more popular prey, predators and parasites. It is im- gardeners select insecticides for use groups of insecticides labeled for portant to select and use insecticides in flower gardens. It lists some of the home use are the pyrethroids, which carefully. common pests associated with flow- come in a variety of names such as When selecting insecticides, buy in ers and some of the active ingredients bifenthrin, cyfluthrin, permethrin and quantities that can be used in a reason- found in insecticides labeled for use esefenvalerate. Many of these com- able amount of time. Look for prod- on ornamental plants. The list contains pounds end in “-thrin,” but not all. ucts that can be used for more than common active ingredients for each Many have a broad spectrum, but the one pest. For example, if a gardener pest from the Kansas pesticide data- lists of pests controlled by each pyre- has problems with aphids and mealy- base. Other effective materials may throid varies. bugs, it might be best to buy a product also be available. Gardeners should Remember that to be a pest, insects that controls both rather than buying check labels carefully and visit local have to be present in substantial num- separate products for each pest. Re- retail outlets to determine which prod- bers. Spotting one or two insects in a member that if it is necessary to treat ucts are best suited for a particular garden should not trigger an insecti- pests several times during the season, pest problem. -

Imidacloprid Fact Sheet

Proposed Groundwater Standards Wis. Admin. Code NR 140 Cycle 10 Imidacloprid How is it used in Wisconsin? A standard will help homeowners and state agencies make Imidacloprid is a neonicotinoid insecticide that is used decisions about future water use and potential public health widely in Wisconsin. It is the active ingredient in a large concerns. number of insecticide products used to control soil insect What are the proposed standards? pests, insects that feed on plant tissues, structures, and pets. • Enforcement standard: 0.2 µg/L (micrograms per liter) Its largest volume of use is in agriculture products as seed • treatments and spraying leaves for corn, soybeans, beans, Preventive action limit standard: 0.02 µg/L potatoes, small grains, vegetables, fruit crops, and more. It is Has this substance been detected above the also used in non-agriculture products in pet and companion proposed groundwater standards? animal collars and sprays, in products for residential trees Yes. Since 2006, for private wells it has been detected in and ornamentals, and in products used in and around homes 55 samples above the proposed enforcement standard and for ants, roaches and other household pests. It was first in 75 samples above the proposed preventive action limit. registered by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency in The highest concentration of imidacloprid detected in a 1994. private well sample by DATCP was 2.19 µg/L. Of the What are some products that contain this 208 monitoring well samples, it has been detected at substance? concentrations of 0.0512–6.7 µg/L. Some common products that use imidacloprid include Where can I find more information? ® ® Admire (soil and leaf pests), Advantage (flea control pet • Information about this and other neonicotinoid ® collars and sprays), Gaucho (seed treatment), Imicide insecticides: ® (ornamental tree pests), Merit (for commercial nurseries https://datcp.wi.gov/Documents/NeonicotinoidReport.pdf ® and lawn and landscape pest control), and Premise (for • Health-based standards: termites and structural pests). -

Prohibited and Restricted Pesticides List Fair Trade USA® Agricultural Production Standard Version 1.1.0

Version 1.1.0 Prohibited and Restricted Pesticides List Fair Trade USA® Agricultural Production Standard Version 1.1.0 Introduction Through the implementation of our standards, Fair Trade USA aims to promote sustainable livelihoods and safe working conditions, protection of the environment, and strong, transparent supply chains.. Our standards work to limit negative impacts on communities and the environment. All pesticides can be potentially hazardous to human health and the environment, both on the farm and in the community. They can negatively affect the long-term sustainability of agricultural livelihoods. The Fair Trade USA Agricultural Production Standard (APS) seeks to minimize these risks from pesticides by restricting the use of highly hazardous pesticides and enhancing the implementation of risk mitigation practices for lower risk pesticides. This approach allows greater flexibility for producers, while balancing controls on impacts to human and environmental health. This document lists the pesticides that are prohibited or restricted in the production of Fair Trade CertifiedTM products, as required in Objective 4.4.2 of the APS. It also includes additional rules for the use of restricted pesticides. Purpose The purpose of this document is to outline the rules which prohibit or restrict the use of hazardous pesticides in the production of Fair Trade Certified agricultural products. Scope • The Prohibited and Restricted Pesticides List (PRPL) applies to all crops certified against the Fair Trade USA Agricultural Production Standard (APS). • Restrictions outlined in this list apply to active ingredients in any pesticide used by parties included in the scope of the Certificate while handling Fair Trade Certified products. -

Toxicological Profile for Toxaphene

TOXAPHENE 199 9. REFERENCES ACGIH. 2009. Chlorinated camphene. In: 2009 TLVs and BEIs: Threshold limit values for chemical substances and physical agents and biological exposure indices. Cincinnati, OH: American Conference of Governmental Industrial Hygienists. Adams RS. 1967. The fate of pesticide residue in soil. J Minn Acad Sci 34:44-48. Adinolfi M. 1985. The development of the human blood-CSF-brain barrier. Dev Med Child Neurol 27(4):532-537. Adlercreutz H. 1995. Phytoestrogens: Epidemiology and a possible role in cancer protection. Environ Health Perspect Suppl 103(7):103-112. Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry. 1989. Decision guide for identifying substance- specific data needs related to toxicological profiles; Notice. Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry, Division of Toxicology. Fed Regist 54(174):37618-37634. Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry. 1990. Biomarkers of organ damage or dysfunction for the renal, hepatobiliary, and immune systems. Subcommittee on Biomarkers of Organ Damage and Dysfunction. Atlanta, GA: Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry. Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry. 2005. Health consultation. Organic chemical residue in schoolyard soils, Goodyear and Burroughs-Mollette Elementary Schools and Risley Middle School and Edo-Miller Park/Lanier Field, city of Brunswick, Glynn County, Georgia. http://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/HAC/pha/OrganicChemicalResidueInSchoolyardSoils/BWKSchoolHCFinal020 905.pdf. June 3, 2010. Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry. 2009. Health consultation. Technical support document for a toxaphene reference dose (RfD) as a basis for fish consumption screening values (FCSVs). State of Michigan. Atlanta, GA: Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry. AIHA. 2010. -

Recommended Classification of Pesticides by Hazard and Guidelines to Classification 2019 Theinternational Programme on Chemical Safety (IPCS) Was Established in 1980

The WHO Recommended Classi cation of Pesticides by Hazard and Guidelines to Classi cation 2019 cation Hazard of Pesticides by and Guidelines to Classi The WHO Recommended Classi The WHO Recommended Classi cation of Pesticides by Hazard and Guidelines to Classi cation 2019 The WHO Recommended Classification of Pesticides by Hazard and Guidelines to Classification 2019 TheInternational Programme on Chemical Safety (IPCS) was established in 1980. The overall objectives of the IPCS are to establish the scientific basis for assessment of the risk to human health and the environment from exposure to chemicals, through international peer review processes, as a prerequisite for the promotion of chemical safety, and to provide technical assistance in strengthening national capacities for the sound management of chemicals. This publication was developed in the IOMC context. The contents do not necessarily reflect the views or stated policies of individual IOMC Participating Organizations. The Inter-Organization Programme for the Sound Management of Chemicals (IOMC) was established in 1995 following recommendations made by the 1992 UN Conference on Environment and Development to strengthen cooperation and increase international coordination in the field of chemical safety. The Participating Organizations are: FAO, ILO, UNDP, UNEP, UNIDO, UNITAR, WHO, World Bank and OECD. The purpose of the IOMC is to promote coordination of the policies and activities pursued by the Participating Organizations, jointly or separately, to achieve the sound management of chemicals in relation to human health and the environment. WHO recommended classification of pesticides by hazard and guidelines to classification, 2019 edition ISBN 978-92-4-000566-2 (electronic version) ISBN 978-92-4-000567-9 (print version) ISSN 1684-1042 © World Health Organization 2020 Some rights reserved. -

Pesticide Residues : Maximum Residue Limits

THAI AGRICULTURAL STANDARD TAS 9002-2013 PESTICIDE RESIDUES : MAXIMUM RESIDUE LIMITS National Bureau of Agricultural Commodity and Food Standards Ministry of Agriculture and Cooperatives ICS 67.040 ISBN UNOFFICAL TRANSLATION THAI AGRICULTURAL STANDARD TAS 9002-2013 PESTICIDE RESIDUES : MAXIMUM RESIDUE LIMITS National Bureau of Agricultural Commodity and Food Standards Ministry of Agriculture and Cooperatives 50 Phaholyothin Road, Ladyao, Chatuchak, Bangkok 10900 Telephone (662) 561 2277 Fascimile: (662) 561 3357 www.acfs.go.th Published in the Royal Gazette, Announcement and General Publication Volume 131, Special Section 32ง (Ngo), Dated 13 February B.E. 2557 (2014) (2) Technical Committee on the Elaboration of the Thai Agricultural Standard on Maximum Residue Limits for Pesticide 1. Mrs. Manthana Milne Chairperson Department of Agriculture 2. Mrs. Thanida Harintharanon Member Department of Livestock Development 3. Mrs. Kanokporn Atisook Member Department of Medical Sciences, Ministry of Public Health 4. Mrs. Chuensuke Methakulawat Member Office of the Consumer Protection Board, The Prime Minister’s Office 5. Ms. Warunee Sensupa Member Food and Drug Administration, Ministry of Public Health 6. Mr. Thammanoon Kaewkhongkha Member Office of Agricultural Regulation, Department of Agriculture 7. Mr. Pisan Pongsapitch Member National Bureau of Agricultural Commodity and Food Standards 8. Ms. Wipa Thangnipon Member Office of Agricultural Production Science Research and Development, Department of Agriculture 9. Ms. Pojjanee Paniangvait Member Board of Trade of Thailand 10. Mr. Charoen Kaowsuksai Member Food Processing Industry Club, Federation of Thai Industries 11. Ms. Natchaya Chumsawat Member Thai Agro Business Association 12. Mr. Sinchai Swasdichai Member Thai Crop Protection Association 13. Mrs. Nuansri Tayaputch Member Expert on Method of Analysis 14.