CHUM SALMON Oncorhynchus Keta (Walbaum)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Review of Potential Impacts of Atlantic Salmon Culture on Puget Sound Chinook Salmon and Hood Canal Summer-Run Chum Salmon Evolutionarily Significant Units

NOAA Technical Memorandum NMFS-NWFSC-53 Review of Potential Impacts of Atlantic Salmon Culture on Puget Sound Chinook Salmon and Hood Canal Summer-Run Chum Salmon Evolutionarily Significant Units June 2002 U.S. DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration National Marine Fisheries Service NOAA Technical Memorandum NMFS Series The Northwest Fisheries Science Center of the Na tional Marine Fisheries Service, NOAA, uses the NOAA Technical Memorandum NMFS series to issue informal scientific and technical publications when complete formal review and editorial processing are not appropriate or feasible due to time constraints. Documents published in this series may be referenced in the scientific and technical literature. The NMFS-NWFSC Technical Memorandum series of the Northwest Fisheries Science Center continues the NMFS-F/NWC series established in 1970 by the Northwest & Alaska Fisheries Science Center, which has since been split into the Northwest Fisheries Science Center and the Alaska Fisheries Science Center. The NMFS-AFSC Technical Memorandum series is now being used by the Alaska Fisheries Science Center. Reference throughout this document to trade names does not imply endorsement by the National Marine Fisheries Service, NOAA. This document should be cited as follows: Waknitz, F.W., T.J. Tynan, C.E. Nash, R.N. Iwamoto, and L.G. Rutter. 2002. Review of potential impacts of Atlantic salmon culture on Puget Sound chinook salmon and Hood Canal summer-run chum salmon evolutionarily significant units. U.S. Dept. Commer., NOAA Tech. Memo. NMFS-NWFSC-53, 83 p. NOAA Technical Memorandum NMFS-NWFSC-53 Review of Potential Impacts of Atlantic Salmon Culture on Puget Sound Chinook Salmon and Hood Canal Summer-Run Chum Salmon Evolutionarily Significant Units F. -

Variation in Salmonid Life Histories: Patterns and Perspectives

United States Department of Agriculture Variation in Salmonid Life Forest Service Histories: Patterns and Pacific Northwest Research Station Perspectives Research Paper PNW-RP-498 Mary F. Willson February 1997 Author MARY F. WILLSON is a research ecologist, Forestry Sciences Laboratory, 2770 Sherwood Lane, Juneau, AK 98801. Abstract Willson, Mary F. 1997. Variation in salmonid life histories: patterns and perspectives. Res. Pap. PNW-RP-498. Portland, OR: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Pacific Northwest Research Station. 50 p. Salmonid fishes differ in degree of anadromy, age of maturation, frequency of repro- duction, body size and fecundity, sexual dimorphism, breeding season, morphology, and, to a lesser degree, parental care. Patterns of variation and their possible signif- icance for ecology and evolution and for resource management are the focus of this review. Keywords: Salmon, char, Oncorhynchus, Salmo, Salvelinus, life history, sexual dimor- phism, age of maturation, semelparity, anadromy, phenology, phenotypic variation, parental care, speciation. Summary Salmonid fishes differ in degree of anadromy, age of maturation, frequency of reproduction, body size and fecundity, sexual dimorphism, breeding season, morphology, and to a lesser degree, parental care. The advantages of large body size in reproductive competition probably favored the evolution of ocean foraging, and the advantages of safe breeding sites probably favored freshwater spawning. Both long-distance migrations and reproductive competition may have favored the evolution of semelparity. Reproductive competition has favored the evolution of secondary sexual characters, alternative mating tactics, and probably nest-defense behavior. Salmonids provide good examples of character divergence in response to ecological release and of parallel evolution. The great phenotypic plasticity of these fishes may facilitate speciation. -

The Effect of Static Magnetic Field on Danube Huchen, Hucho Hucho (L.) Sperm Motility Parameters

Arch. Pol. Fish. (2013) 21: 189-197 DOI 10.2478/aopf-2013-0016 RESEARCH ARTICLE The effect of static magnetic field on Danube huchen, Hucho hucho (L.) sperm motility parameters Krzysztof Formicki, Joanna Szulc, Adam Tañski, Agata Korzelecka-Orkisz, Andrzej Witkowski, Przemys³aw Kwiatkowski Received – 21 May 2013/Accepted – 01 August 2013. Published online: 30 September 2013; ©Inland Fisheries Institute in Olsztyn, Poland Citation: Formicki K., Szulc J., Tañski A., Korzelecka-Orkisz A., Witkowski A., Kwiatkowski P. 2013 – The effect of static magnetic field on Danube huchen, Hucho hucho (L.) sperm motility parameters – Arch. Pol. Fish. 21: 189-197. Abstract. The distribution range of Danube huchen, Hucho exposing sperm to magnetic fields might, after more extensive hucho (L.) in Polish waters is decreasing, and is currently only studies, could be used for short-term sperm storage. 25 to 30% of its original area. Since few data are available concerning Danube huchen, it is necessary to develop a better Keywords: Huchen, sperm motility (CASA), morphology, understanding of its reproduction to improve artificial fertilization, magnetic field spawning in hatcheries. Eight sperm motility parameters were assessed using CASA after short-term storage in a static magnetic field. The effect of magnetic field exposure on spermatozoa at fertilization and on sperm morphology (SEM) Introduction was also examined. Static magnetic fields had a positive effect on sperm motility parameters, including VCL, which The Danube huchen, Hucho hucho (L.), is the largest determines fertilization effectiveness; values for this representative of the Salmonidae. Until recently, the parameter after a 24 h exposure period to fields of different species inhabited the Danube River and most of its intensity were as follows: 1 mT – 110.09 μm s-1;5mT– -1 -1 submontane tributaries. -

Acquisition of Potential for Sperm Motility in Rainbow Trout and Chum Salmon

J. exp. Biol. 126, 89-96 (1986) 89 Printed in Great Britain © The Company of Biologists Limited 1986 ACQUISITION OF POTENTIAL FOR SPERM MOTILITY IN RAINBOW TROUT AND CHUM SALMON BY SACHIKO MORISAWA Biological Laboratory, St Marianna University, School of Medicine, 2095 Sugao, Miyamae-ku, Kawasaki 213, Japan AND MASAAKI MORISAWA Laboratory of Physiology, Ocean Research Institute, University of Tokyo, 1-15-1 Minamidai, Nakano-ku, Tokyo 164, Japan Accepted 17 July 1986 SUMMARY The male reproductive organ of rainbow trout and chum salmon consists of a pair of testes and sperm ducts. Spermatozoa in the distal portion of the sperm ducts exhibit full motility in the K+-free medium. However, spermatozoa from the testis were almost immotile in this medium. This suggests that the spermatozoa acquire a capacity for movement during their passage from the testis along the sperm duct. In chum salmon migrating into a bay, the sperm duct was almost empty. However, after the fish have travelled upstream for 1 km to their spawning ground in the river, the spermatozoa have left the testis, moved into the sperm duct and are capable of becoming motile. Thus it is probable that the process of acquiring the ability to move occurs within a relatively short period in this simple reproductive organ. Additionally, testicular spermatozoa demembranated with Triton X-100 exhibited motility, although the motility was less than that of demembranated spermatozoa from the sperm duct, suggesting that the acquisition of motility may correspond with the development of some function of the plasma membrane. INTRODUCTION Since Tournade (1913) demonstrated that mammalian spermatozoa acquire mo- tility during transit through the epididymis from the caput to the cauda after spermiation, much effort has been devoted to understanding the mechanism of this phenomenon (Hoskins, Brandt & Acott, 1978). -

Official Fish List

State-Fish Art Contest Official Fish List Freshwater Fish Species SUNFISH FAMILY SALMONIDAE (SALMON) FAMILY Bluegill Lepomis macrochirus Apache Trout—WNTA Oncorhynchus apache Florida Largemouth Bass Micropterus salmoides floridanus Arctic grayling—WNTA Thymallus arcticus Guadalupe Bass Micropterus treculii Blueback Char Salvelinus alpinus oquassa Largemouth Bass Micropterus salmoides Bull Trout—WNTA Salvelinus confluentus Longear Sunfish Lepomis megalotis California Golden Trout—WNTA Oncorhynchus aguabonita White Bass (Sand Bass) Morone chrysops Gila Trout—WNTA Oncorhynchus gilae Smallmouth Bass Micropterus dolomieu Landlocked Atlantic Salmon Salmo salar Spotted Bass Micropterus punctulatus Rainbow Trout Oncorhynchus mykiss Suwannee Bass Micropterus notius Brook Trout Salvelinus fontinalis PIKE FAMILY Southern Appalachian Brook Trout Muskellunge Esox masquinongy West Virginia Golden Brook Trout Northern Pike Esox lucius Cutthroat Trout Oncorhynchus clarkii PERCH FAMILY Bonneville Cutthroat Trout—WNTA Oncorhynchus clarkii utah Walleye Sander vitreus Coastal Cutthroat Trout —WNTA Oncorhynchus clarkii clarkii White Perch Morone americana Colorado River Cutthroat Trout —WNTA Oncorhynchus clarkii pleuriticus Greenback Cutthroat Trout—WNTA Oncorhynchus clarki stomias CATFISH FAMILY Lahontan Cutthroat Trout—WNTA Oncorhynchus clarkii henshawi Channel Catfish Ictalurus punctatus Rio Grande Cutthroat Trout—WNTA Oncorhynchus clarkii virginalis Yaqui Catfish Ictalurus pricei Westslope Cutthroat Trout—WNTA Oncorhynchus clarkii lewisi Yellowstone Cutthroat -

Information Reports

INFORMATION REPORTS NUMBER 2020-03 FISH DIVISION Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife Migration rates of hatchery Chum Salmon (Oncorhynchus keta) fry in the Columbia River estuary 1 Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife prohibits discrimination in all of its programs and services on the basis of race, color, national origin, age, sex or disability. If you believe that you have been discriminated against as described above in any program, activity, or facility, or if you desire further information, please contact ADA Coordinator, Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife, 4034 Fairview Industrial Drive SE, Salem, OR 97302 503-947-6000. This material will be furnished in alternate format for people with disabilities if needed. Please call 541-757-4263 to request 2 Migration rates of hatchery Chum Salmon (Oncorhynchus keta) fry in the Columbia River estuary Kristen Homel1 and G. Curtis Roegner2 1Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife 17330 SE Evelyn Street Clackamas, Oregon 97015, USA [email protected] (971) 673-0578 2NOAA Fisheries, Northwest Fisheries Science Center Point Adams Field Station 520 Heceta Place Hammond, Oregon 97121, USA May 2020 3 TABLE OF CONTENTS Abstract ............................................................................................................................................................ 5 Introduction ...................................................................................................................................................... 6 Methods .......................................................................................................................................................... -

Eagle Island Chum Salmon Spawning Channel Project Todd Hillson, Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife Outline

Eagle Island Chum Salmon Spawning Channel Project Todd Hillson, Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife Outline • Brief historical overview of Lower Columbia River (LCR) chum salmon • LCR chum salmon limiting factors • Why is this project important for recovery of LCR chum salmon • A time-line and funding history of the Eagle Island spawning channel project • Overview of the design • Pre-proposal comments & questions Historic Overview Based on commercial landings & habitat, 0.5 - 1 million chum salmon returned to Columbia River basin (ISAB 2015-1) • Upper Distribution Celilo Falls Decline in the 1940’s • Loss, degradation, and impeded access to spawning habitat • Changes to estuary ecology and habitat • Altered mainstem & tributary hydrology • Harvest Endangered Species Act (ESA) • Currently, between 1,000s & 10,000s of chum salmon return to the LCR • 17 historic populations in the Columbia River (90% of which are extirpated) • Limited current distribution (Mostly in Washington) • Listed as Threatened under Endangered Species Act in 1999 • 1 ESU for Lower Columbia River • Divided into 3 geographic stratum (Coast, Cascade & Gorge) Lower Columbia River Salmon and Steelhead ESA Recovery Plan, NOAA - 2013 LCR Chum Salmon Limiting Factors Harvest Hydro Hatcheries Habitat Limiting Factor - Harvest Commercial Harvest 1866-1996 Historic Catch • Annual Landings of adults ranged from 100-500K adults • Appropriate harvest rate for a healthy population of chum salmon is 48% (Chapman 1986) • Fisheries Managers reduced harvest in 1950s due to Commercial Fish Ticket and SAFE harvest 400000 1938-2001 declines in abundance Current Harvest • Harvest prohibited on LCR chum salmon Number of chum of Number 100000 • Incidental impacts in Chinook and/or coho salmon targeted 0 commercial fisheries limited 1940 1950 1960 1970 1980 1990 2000 to <5%. -

Fish Smoking Procedures for Forced Convection Smokehouses

Fish Smoking Procedures for Forced Convection Smokehouses revised May 23, 2001 by Kenneth S. Hilderbrand, Jr. Seafood Processing Specialist Oregon State University Extension Sea Grant Program Hatfield Marine Science Center Newport, Oregon 97365 Oregon State University Extension Service Sea Grant ORESU-I-01-001 This publication can be downloaded from: http://seagrant.orst.edu/sgpubs/onlinepubs/i01001.pdf 2 Table of Contents Table of Contents ..........................................................................................................................................2 Table of Figures ............................................................................................................................................3 List of Tables.................................................................................................................................................3 DISCLAIMER: TRADE NAMES ................................................................................................................4 REGULATIONS AND TERMINOLOGY ...................................................................................................4 INFORMATION SOURCES ........................................................................................................................6 SMOKED FOOD PRESERVATION AND CHANGING PRACTICES......................................................6 SMOKED FISH PRESERVATION..............................................................................................................7 Salt Affects -

Salmon Identification

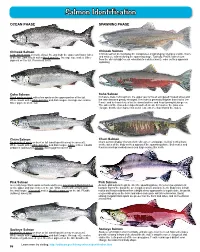

Salmon Identification OCEAN PHASE SPAWNING PHASE Chinook Salmon Chinook Salmon Large black spots on back, dorsal fin, and both the upper and lower lobes Chinook salmon do not display the conspicuous morphological changes of pink, chum, of the tail. Dark mouth with a black gum line. Average size scales. Silver and sockeye salmon during the spawning stage. Typically, Pacific salmon turn pigment on the tail. Prominent teeth. from the silvery bright ocean coloration to a darker bronze color as they approach spawning. Coho Salmon Coho Salmon Black spots on back with a few spots on the upper portion of the tail. In mature male coho salmon, the upper jaw forms an elongated hooked snout and White mouth with a white gum line and dark tongue. Average size scales. the teeth become greatly enlarged. The male is generally brighter than that of the Silver pigment on the tail. female and is characterized by the dorsal surface and head turning bluish-green. The sides of the males develop a broad red streak. In females, the jaws also elongate but the development is much less extreme than that of the males. Chum Salmon Chum Salmon No prominent spots on back or tail (small speckles may be present). Chum salmon display characteristic olive-green and purple (calico) vertical bars White mouth with a white gum line and dark tongue. Large scales. Caudal on the sides of the body as they approach the spawning phase. Both males and peduncle (tail base) is slender. Silver pigment on the tail. females develop hooked noses and large canine-like teeth Pink Salmon Pink Salmon Generally large black spots on back and heavy oval shaped black blotches As male pink salmon begin to enter the spawning phase, they develop a prominent on the upper and lower lobes of the tail. -

Synopsis of Biological Data on the Chum Salmon Oncorhynchus Keta

FAO Fisheries Synopsis No. 41 BCF/S 41 SAST Chum ea1mon - 1,23(O1),009,03 SYNOPSIS OF BlOLOGîCAL DATA ON THE CHUM SALMON,, Oncorhy.nchus kéta (Wàîba urn) 1792 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR U.S. FISH AND WILDLIFE SERVICE BUREAU OF COMMERCIAL FISHERIES Circular 315 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR Walter J. Hickel, Secretary Russell E. Train, Under Secretary Leslie L. Glasgow, Assistant Secretary for Fish and Wildlife, Parks, and Marine Resources Charles H. Meacham, Comlni8eioner, U.S. FISH AND WILDUJFE SERVICE Philip M. Roedel, Director, BUREAU OF COMMERCIAL FISHERIES Synopsis of Biological Data onthe Chum Salmon, Oncorhynchus keta (Walbaum) 1792 By RICHARD G. BAKKALA FAO Species Synopsis No, 41 Circular 315 Washington, D.C. March 1970 CONTENTS Pag e Introduction i Identity i 1.1 Nomenclature i 1.2 Taxonomy i 1.3 Morphology 5 2 Distribution 8 2.1Total areas 8 2.2 Differential distribution 9 2.3 Determinants of distribution 10 2.4 Hybridization il 3 Bionomics and life history 12 3.1 Reproduction 12 3.2 Preadult phase 24 3.3 Adult phase 28 3.4 Nutrition and growth ¿9 3.5 Behavior 39 4 Population 42 4.1 Structure 42 4.2 Abundance and density (of population) 46 4.3 Natality and recruitment 50 4.4 Mortality and morbidity 51 4.5 Dynamics of population 57 4.6 Population in community and ecosystem 59 5 Fishery 60 5.1 Fishing equipment 60 5.2 Fishing areas 64 5.3 Fishing seasons 65 5.4 Fishing operations and results 65 6 Protection and management . -

Danube Salmon

Danube Salmon (Hucho hucho) in Central and South Eastern Europe: A Review for the Development of an International Program for the Rehabilitation and Conservation of Danube Salmon Populations Andrada IHUŢ1), Andreas ZITEK2), Steven WEISS3), Clemens RATSCHAN4), Georg HOLZER5), Thomas KAUFMANN6), Daniel COCAN1), Radu CONSTANTINESCU1), Vioara MIREŞAN*1) 1) Faculty of Animal Science and Biotechnologies, University of Agricultural Sciences and Veterinary Medicine Cluj-Napoca, Romania 2) Department of Chemistry, VIRIS Laboratory for Analytical Ecogeochemistry, University of Natural Resources and Life Sciences Vienna, Austria; [email protected] 3) Institute of Zoology, Karl-Franzens University Graz, Austria; [email protected] 4) ezb / TB Zauner GmbH, Technical Ofice for Applied Aquatic Ecology, Fisheries, Environmental Engineering, Austria; [email protected] 5) Engineering ofice for landscape planning and landscape management, Austria; holzer.georg@chello. at 6) Freiwasser, Association for Ecology, Environmental Engineering, Austria; [email protected] *Corresponding author, email: [email protected] Bulletin UASVM Animal Science and Biotechnologies 71(2) / 2014, Print ISSN 1843-5262; Electronic ISSN 1843-536X DOI:10.15835/buasvmcn-asb:10815 Abstract Danube salmon Hucho hucho (L.), known as one of the world’s largest salmonids, is among the most endangered ish species inhabiting the Danube basin of Central Europe. It is classiied as endangered (EN) by the IUCN due to its very low abundance and continual decline. Historically, the natural distribution range of the Danube salmon included drainages in Austria, Bosnia-Herzegovina, Montenegro, north-western Croatia, Czech Republic, Germany, Poland, Romania, Serbia, Slovakia, Slovenia and western Ukraine. Currently, Danube salmon populations are fragmented within the Danube drainage, with many being supported by artiicial reproduction and stocking programs. -

ICES Marine Science Symposia

II. Fish ICES mar. Sei. Symp., 194: 31-55. 1992 Pacific salmon in Atlantic waters Yves Harache Harache, Y. 1992. Pacific salmon in Atlantic waters. - ICES mar. Sei. Symp., 194:31-55. A century of Pacific salmon introductions to Atlantic waters is summarized. Move ments of fish were initiated in the last century, and in many countries large quantities of eggs have been introduced into rivers on both sides of the North Atlantic Ocean. The motivations for such programmes, the techniques used, and the results arc analysed for most of the documented attempts to introduce these species in the Atlantic area, with special attention being given to recent introductions (since 1950). Programmes for the introduction of Pink salmon (Oncorhynchus gorbuscha) in Newfoundland (Canada) and the Kola Peninsula (USSR) are reviewed in detail, and the use of coho salmon (Oncorhynchus kisutch) for ranching (New Hampshire, USA) and farming (Europe) is described. Pacific salmon released in Atlantic oceanic areas have shown in most cases an aptitude for survival, growth, homing, and spawning, even in areas where environmental characteristics are substantially different from their home waters. Survival rates are generally lower than in the original range and straying relatively important. However, in spite of significant returns, all attempts to establish reproducing sea-going populations have failed in the northern hemisphere. Although not developing rapidly, the use of coho salmon for aquaculture in Europe has an interesting potential. The possible causes of success or failure of the different attempts are discussed; they include an analysis of the adaptive mechanisms of populations which exist in their original habitat, and the influence of the ecological characteristics of the receiving country on the biology of the species.