Noun Phrase Conjunction in Three Puyuma Dialects*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Consonant Insertions: a Synchronic and Diachronic Account of Amfo'an

Consonant Insertions: A synchronic and diachronic account of Amfo'an Kirsten Culhane A thesis submitted for the degree of Bachelor ofArts with Honours in Language Studies The Australian National University November 2018 This thesis represents an original piece of work, and does not contain, inpart or in full, the published work of any other individual, except where acknowl- edged. Kirsten Culhane November 2018 Abstract This thesis is a study of synchronic consonant insertions' inAmfo an, a variety of Meto (Austronesian) spoken in Western Timor. Amfo'an attests synchronic conso- nant insertion in two environments: before vowel-initial enclitics and to mark the right edge of the noun phrase. This constitutes two synchronic processes; the first is a process of epenthesis, while the second is a phonologically conditioned affixation process. Which consonant is inserted is determined by the preceding vowel: /ʤ/ occurs after /i/, /l/ after /e/ and /ɡw/ after /o/ and /u/. However, there isnoregular process of insertion after /a/ final words. This thesis provides a detailed analysis of the form, functions and distribution of consonant insertion in Amfo'an and accounts for the lack of synchronic consonant insertion after /a/-final words. Although these processes can be accounted forsyn- chronically, a diachronic account is also necessary in order to fully account for why /ʤ/, /l/ and /ɡw/ are regularly inserted in Amfo'an. This account demonstrates that although consonant insertion in Amfo'an is an unusual synchronic process, it is a result of regular sound changes. This thesis also examines the theoretical and typological implications 'of theAmfo an data, demonstrating that Amfo'an does not fit in to the categories previously used to classify consonant/zero alternations. -

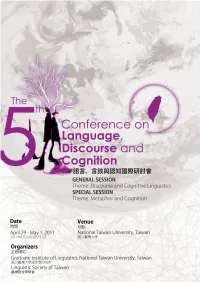

Conference on Language, Discourse and Cognition 第五屆語言、言談與認知國際研討會

CLDC 2011 The 5th Conference on Language, Discourse and Cognition 第五屆語言、言談與認知國際研討會 General Theme: Discourse and Cognitive Linguistics Special Theme: Metaphor and Cognition Date: April 29th – May 1st, 2011 Venue: Tsai Lecture Hall, National Taiwan University Organizers: Graduate Institute of Linguistics, National Taiwan University Linguistic Society of Taiwan Table of Contents Introduction............................................................................................................................................. 1 Organizers................................................................................................................................................. 2 Guidelines ................................................................................................................................................. 3 Program...................................................................................................................................................... 4 PRESENTATIONS Keynote Speech 1. Conceptual Integration across Discourse Gilles Fauconnier ............................................................................................................................. 11 2. Image Grammar and Embodied Rhetoric—A New Approach to Cognitive Linguistics Masa-aki Yamanashi ..................................................................................................................... 12 3. A Two-tiered Analysis of the Case Markers in Formosan Languages Shuanfan Huang ............................................................................................................................. -

BOOK of ABSTRACTS June 28 to July 2, 2021 15Th ICAL 2021 WELCOME

15TH INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON AUSTRONESIAN LINGUISTICS BOOK OF ABSTRACTS June 28 to July 2, 2021 15th ICAL 2021 WELCOME The Austronesian languages are a family of languages widely dispersed throughout the islands of The name Austronesian comes from Latin auster ICAL The 15-ICAL wan, Philippines 15th ICAL 2021 ORGANIZERS Department of Asian Studies Sinophone Borderlands CONTACTS: [email protected] [email protected] 15th ICAL 2021 PROGRAMME Monday, June 28 8:30–9:00 WELCOME 9:00–10:00 EARLY CAREER PLENARY | Victoria Chen et al | CHANNEL 1 Is Malayo-Polynesian a primary branch of Austronesian? A view from morphosyntax 10:00–10:30 COFFEE BREAK | CHANNEL 3 CHANNEL 1 CHANNEL 2 S2: S1: 10:30-11:00 Owen Edwards and Charles Grimes Yoshimi Miyake A preliminary description of Belitung Malay languages of eastern Indonesia and Timor-Leste Atsuko Kanda Utsumi and Sri Budi Lestari 11:00-11:30 Luis Ximenes Santos Language Use and Language Attitude of Kemak dialects in Timor-Leste Ethnic groups in Indonesia 11:30-11:30 Yunus Sulistyono Kristina Gallego Linking oral history and historical linguistics: Reconstructing population dynamics, The case of Alorese in east Indonesia agentivity, and dominance: 150 years of language contact and change in Babuyan Claro, Philippines 12:00–12:30 COFFEE BREAK | CHANNEL 3 12:30–13:30 PLENARY | Olinda Lucas and Catharina Williams-van Klinken | CHANNEL 1 Modern poetry in Tetun Dili CHANNEL 1 CHANNEL -

Lancini Jen-Hao Cheng [email protected]

Lancini Jen-hao Cheng [email protected] Ens.hist.teor.arte Afiliación institucional Investigador Independiente Lancini Jen-hao Cheng, “Native Terminology and Classification of Taiwanese Musical Instruments”, Lancini Jen-hao Cheng, nacido en Ensayos. Historia y teoría del arte, Bogotá, D. C., Taiwan finalizó sus estudios de PhD en Universidad Nacional de Colombia, Vol. XIX, el Department of Music, University of No. 28 (enero-junio 2015), pp. 65-139. Otago de Nueva Zelanda en Agosto de 2015. Obtuvo también el grado M.Litt. en ABSTRACT Ethnología y Folklore en el Elphinstone This study aims to be a comprehensive investigation into Institute, University of Aberdeen, Escocia, the native terminology and classification of Taiwanese aboriginal musical instruments based on ethnographic Reino Unido. Además, se ha desempeñado fieldwork. Its main result is new information concerning por espacio de catorce años como profesor indigenous instruments and taxonomic schemes and above de música y artes y humanidades en su all the discovery of many unknown musical instruments país. Sus principales intereses investigativos from different aboriginal groups (Bunun, Kavalan, Pazih- son la etnomusicología y la organología Kahabu, Puyuma, Rukai, Sakizaya, Siraya and Tsou). Concluding, many factors influence Taiwanese native así como la exploración de contextos classifications of musical instruments and they include interpretativos en la música tradicional. linguistic factors, playing techniques, materials used in their construction, performance contexts, as well as gender, social status and religion. Key Words Taiwan, Classification, Native terminology, musical instruments TÍtulo Terminología local y clasificación de los instrumentos musicales de Taiwan RESUMEN Este estudio intenta ser una investigación exhaustiva de la terminología y sistemas de clasificación de los instrumentos musicales de los aborígenes de Taiwan con base en trabajo etnográfico de campo. -

Research Note

Research Note The Austronesian Comparative Dictionary: A Work in Progress Robert Blust and Stephen Trussel UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI‘I AT MĀNOA AND TRUSSEL SOFTWARE DEVELOPMENT The Austronesian comparative dictionary (ACD) is an open-access online resource that currently (June 2013) includes 4,837 sets of reconstructions for nine hierarchically ordered protolanguages. Of these, 3,805 sets consist of single bases, and the remaining 1,032 sets contain 1,032 bases plus 1,781 derivatives, including affixed forms, reduplications, and compounds. His- torical inferences are based on material drawn from more than 700 attested languages, some of which are cited only sparingly, while others appear in over 1,500 entries. In addition to its main features, the ACD contains sup- plementary sections on widely distributed loanwords that could potentially lead to erroneous protoforms, submorphemic “roots,” and “noise” (in the information-theoretic sense of random lexical similarity that arises from historically independent processes). Although the matter is difficult to judge, the ACD, which prints out to somewhat over 3,000 single-spaced pages, now appears to be about half complete. 1. INTRODUCTION. 1 The December 2011 issue of this journal carried a Research Note that described the history and present status of POLLEX, the Polynesian Lexicon project initiated by the late Bruce Biggs in 1965, which over time has grown into one of the premier comparative dictionaries available for any language family or major subgroup (Greenhill and Clark 2011). A theme that runs through this piece is the remark- able growth over the 46 years of its life (at that time), not just in the content of the dictio- nary, but in the technological medium in which the material is embedded. -

University of California Santa Cruz

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA SANTA CRUZ TRANSMEDIA ARTS ACTIVISM AND LANGUAGE REVITALIZATION: CRITICAL DESIGN, ETHICS AND PARTICIPATION IN THIRD DIGITAL DOCUMENTARY A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in FILM AND DIGITAL MEDIA by Anita Wen-Shin Chang June 2016 The Dissertation of Anita Wen-Shin Chang is approved: ____________________________________ Professor Soraya Murray, chair ____________________________________ Professor Jennifer A. González ____________________________________ Professor Jonathan Kahana ____________________________________ Professor Lisa Nakamura ____________________________________ Tyrus Miller Vice Provost and Dean of Graduate Studies Copyright © by Anita W. Chang 2016 TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Figures iv Abstract vi Dedication viii Acknowledgements ix Introduction 1 CHAPTER 1 A Discourse of “Image Sovereignty”: Variations on an Ideal/Image of Native Self-representation 15 2 Digital Documentary Praxis: Tongues of Heaven 45 3 An Essay on Editing Tongues of Heaven 93 4 Networked Audio-Visual Culture and New Digital Publics 123 5 Documentary and Online Transmediality: Tongues of Heaven/Root Tongue 166 Conclusion 228 Supplemental File 235 Bibliography 236 Filmography 254 iii LIST OF FIGURES 1. 228 Hand-in-Hand Rally, Northern Taiwan (Central News Agency) 2 1.1. Merian Cooper and Ernest Schoedsack during the production of Grass 18 1.2. Animated map of disputed territory in You Are On Indian Land 24 1.3. Mike Mitchell speaks to Canadian government representatives in You Are On Indian Land. 27 1.4. Mike Mitchell and protestors speak with Cornwall police. 29 1.5. Cornwall police force protestors into cars heading to jail. 29 1.6. Still from You Are On Indian Land 31 1.7. -

LCSH Section T

T (Computer program language) T cell growth factor T-Mobile G1 (Smartphone) [QA76.73.T] USE Interleukin-2 USE G1 (Smartphone) BT Programming languages (Electronic T-cell leukemia, Adult T-Mobile Park (Seattle, Wash.) computers) USE Adult T-cell leukemia UF Safe, The (Seattle, Wash.) T (The letter) T-cell leukemia virus I, Human Safeco Field (Seattle, Wash.) [Former BT Alphabet USE HTLV-I (Virus) heading] T-1 (Reading locomotive) (Not Subd Geog) T-cell leukemia virus II, Human Safeco Park (Seattle, Wash.) BT Locomotives USE HTLV-II (Virus) The Safe (Seattle, Wash.) T.1 (Torpedo bomber) T-cell leukemia viruses, Human BT Stadiums—Washington (State) USE Sopwith T.1 (Torpedo bomber) USE HTLV (Viruses) t-norms T-6 (Training plane) (Not Subd Geog) T-cell receptor genes USE Triangular norms UF AT-6 (Training plane) BT Genes T One Hundred truck Harvard (Training plane) T cell receptors USE Toyota T100 truck T-6 (Training planes) [Former heading] USE T cells—Receptors T. rex Texan (Training plane) T-cell-replacing factor USE Tyrannosaurus rex BT North American airplanes (Military aircraft) USE Interleukin-5 T-RFLP analysis Training planes T cells USE Terminal restriction fragment length T-6 (Training planes) [QR185.8.T2] polymorphism analysis USE T-6 (Training plane) UF T lymphocytes T. S. Hubbert (Fictitious character) T-18 (Tank) Thymus-dependent cells USE Hubbert, T. S. (Fictitious character) USE MS-1 (Tank) Thymus-dependent lymphocytes T. S. W. Sheridan (Fictitious character) T-18 light tank Thymus-derived cells USE Sheridan, T. S. W. (Fictitious -

The Typology of Nominalization*

LANGUAGE AND LINGUISTICS 13.4:803-844, 2012 2012-0-013-004-000308-1 The Typology of Nominalization* Review article on: Foong Ha Yap, Karen Grunow-Hårsta and Janick Wrona. Nominalization in Asian Languages: Diachronic and Typological Perspectives. Amsterdam & Philadelphia: John Benjamins, 2011. Matthias Gerner City University of Hong Kong In this review article, I propose a new organization of the data in Yap, Grunow-Hårsta & Wrona (2011)’s edited volume on nominalization in about sixty Asian languages. The chapters lack systemic integration into a coherent system. There is no systematic exposition of the logically possible expression types of each variable. The editors do not systematically identify nominalizers with specialized functions. This article classifies the data contained in the volume into a logical system of morphological, syntactic, semantic, pragmatic and diachronic types. Key words: nominalization, specialized nominalizers, logical types 1. Introduction This volume consists of twenty-six chapters on nominalization in about sixty languages spoken in Asia: one Indo-European, eighteen Tibeto-Burman, three Sinitic, one Korean, two Japanese, thirty-one Austronesian and one Trans-New-Guinea languages. Most chapters concentrate on one language (e.g. Rhee on Korean), several chapters survey small groups of languages (e.g. Noonan on Tamangic). All papers are descriptive but vary in the coverage of syntactic, semantic, pragmatic and diachronic phenomena. This compilation of new, mainly undescribed, data on nominalization offers new insights on typological research of other authors (Comrie & Thompson 1985). In the introduction (Yap, Grunow-Hårsta & Wrona 2011:1-57), the editors YG-HW summarize certain facts discussed by the contributors but do not systemically integrate the data. -

賽夏語詞彙的結構與語義研究 a Morphological and Semantic Study on Word Formation in Saysiyat

國立新竹教育大學臺灣語言與語文教育研究所 Graduate Institute of Taiwan Languages And Language Education National Hsin-chu University of Education 碩士論文 Master Thesis 賽夏語詞彙的結構與語義研究 A Morphological and Semantic Study on Word Formation in SaySiyat 指導教授:葉美利 Adviser: Dr. Marie Meili Yeh 研究生:高清菊 By ya’aw kalahae’ kaybaybaw 中華民國九十八年七月 July 2009 i 摘 要 本論文旨在探討賽夏語詞彙的結構與語義。賽夏語詞彙的結構有三種,分別 為衍生結構(derivation) 、重疊結構(reduplication) 和複合結構(compounding) ,其中 以衍生結構數量最為豐富且語義多樣。 第一章介紹賽夏語的基本背景、語法簡介。第二章是相關文獻的回顧。第三 章討論賽夏語的衍生結構、重疊結構以及複合結構。賽夏語的衍生結構依詞綴出 現的位置比較,發現前綴的數量最多,環綴次之,中綴及後綴最少;賽夏語的重 疊結構豐富,有 Ca-、CV-、CVC-、Full 等重疊,語義豐富且多樣,是賽夏語的 主要構詞之一;複合結構數量不多,有時需加入格位或連詞才能形成語義。第四 章是將前綴部分依承載的語義分為空間與移動、變化及動作等類別,並比較同類 屬的前綴語義間的差別;屬「動作」的前綴相較於其他語義的前綴數量較多,也 印證文化上對於重視的事物,不但表現豐富,而且出現頻率較高。.第五章從語言 看文化。語言是一種文化現象,例如表示「吃」的詞彙,除了 si’ael 之外,還有 前綴 San-、pa:-、ko-有分工現象,有時也可互通語義。也討論姓氏名是人群識別 的標誌,也是居住地的地理特徵描述。從這些詞彙的解構可以看到語言、文化、 環境之間的關係。第六章則將本論文的研究發現加以整合與歸納,並提出一些本 論文的貢獻與缺失,以及未來可繼續研究的方向與目標。 關鍵詞:賽夏語、構詞、衍生、重疊、複合、語義、前綴。 ii Abstract This thesis aims to discuss the lexical structures of Saisiyat and their derivational meanings. There are three lexical structures in Saisiyat, derivation, reduplication and compounding. Among these structures, derivation is productive, and it has more diverse meanings. Chapter 1 provides a sketch of Saiiyat. Chapter 2 is literature review. Chapter 3 discusses the structure of derivation, reduplication and compounding. Compared the affixes in Saisiyat, prefixes are the most, circumfixes are less, and infixes and suffixes are the least. The reduplication, includes Ca-, CV-, CVC- and full reduplication, is abundant and various. Reduplication is one of the main word formations of Saysiyat. There are few words formed by compounding because they need case markers or conjunctions to form new meanings. In Chapter 4, according to the meanings, affixes are divided into three categories, including space and movement, change as well as action, and we compare the meanings of the affixes. -

An Overview of Saisiyat Morphology Elizabeth Zeitoun

An overview of Saisiyat morphology Elizabeth Zeitoun (Academia Sinica) ABSTRACT Among the fourteen Formosan languages, Saisiyat forms a small communalect, both in terms of population (estimated at 6,200 as of the end of 2012 -- http://www.apec.gov.tw) and diffusion of the language. Saisiyat is divided into two major dialects, Taai (shaykilapa: [Sajkilapa˘] in Saisiyat), known as the Northern dialect, spoken in Wufeng Township, Hsinchu County and Tungho (shaymahahebon [Sajmahah´Bon] in Saisiyat), referred to as the Southern dialect, spoken in Nanchuang and Shihtan Townships, Miaoli County (see Map 1). The major difference between these two dialects is said to lie in their phonologies: the voiced flap /R/ is preserved in Taai but has been lost in Tungho (Li 1978). The Tungho dialect is spoken by three communities (’aehae’ baala’ [/QhQ/ Baala/]) which are delimited by three different rivers (see Map 2), viz. Tungho shaywalo’ [Sajwalo/], Penglai shayrai’in [Sajrai/in] and Shihtan shayshawi’ [SajSawi/], dispersed in a number of villages (’aehae ’asang [/QhQ/ /asaŋ]). Map 1: Distribution of the Saisiyat dialects r e v i R . S Shangping River Shangping n a r u e h iv C R n . ta E ih h S 1 The present talk, based on a monograph of about 600 pages on the same topic, will provide an overview of Tungho Saisiyat verbal morphology, by focusing on nominal and verbal morphology. Selected references Kaybaybaw, Ya’aw Kalahae’. 2009. A Morphological and Semantic Study on Word Formation in Saisiyat. M.A. thesis. Hsinchu: National Hsinchu University of Education. [in Chinese] Li, Paul Jen-kuei. -

The Revitalization of Saisiyat

StartingStarting fromfrom thethe villages:villages: TheThe revitalizationrevitalization ofof SaisiyatSaisiyat DongheDonghe ElementaryElementary SchoolSchool ChingChing ChuChu GaoGao Distribution • Saisiyat: living in the mountain areas between Hsinchu and Miaoli; next to the Atayal and Hakka • Mainly distributed in Nanchuang and Shitan Townships, Miaoli County, and Wufeng township in Hsinchu County; divided into southern and northern groups • High rate of outward migration (Total population of migration: 6192 till June 2015) • Social system mainly consists of patrilineal clanships. Traditionally, each clanship has its own symbol. The beginning... • Reconstruction of villages, subproject of the community development project conducted by the Council for Cultural Affairs, 2001 • Key model of indigenous villages project conducted by the Council of Indigenous People, 2005 • Project of lexicography of indigenous languages: Saisiyat, 2007 • The project on revitalization of endangered languages, has been conducted since 2012 A. Work lists for 2012 1. Establishing language conservation and development group 2. Investigating and building databases of basic information 3. Establishing volunteer groups 4. Recording elders 5. Implementing Master-Apprentice language learning programs 6. Language learning families 7. Intensifying aboriginal language proficiency 8. Encouraging speaking native languages at conferences B. Work lists for 2013 1. The Saisiyat language conservation and development group 2. Employing full-time staff and volunteers groups 3. Project of recording elders 4. Implementing Master-Apprentice language learning program 5. Language learning families 6. Annual presentation of accomplishment of the project 7. Indigenous language learning program 8. Digital video programs of indigenous languages and e- learning books 9. Creating fine learning environments in the villages and intensifying promotion of the concept of learning indigenous languages 10. -

Two Aspectual Puzzles in Saisiyat

Two Aspectual Puzzles in Saisiyat 1. Introduction: Two Puzzles with [ila] In this paper I investigate two puzzles with the Saisiyat aspect marker [ila]. With states and activities, [ila] gives two distinct readings: a universal perfect reading and an inchoative reading (Puzzle One). These two readings can be illustrated by the following scenario: at first, Ataw weighed 100 kg. Over time he lost some weight, and has gotten comparatively skinnier. Now he only weighs 70 kg, which is still quite large in Taiwan. Both (1-2) are felicitous in this scenario, with different aspectual meanings despite analogous surface structure. 1) Ataw balih ila Ataw skinny ILA “Ataw has become/gotten skinny(-ier)” 2) Ataw kerpee ila Ataw fat ILA “Ataw has been and is (still) fat” The difference in meaning between (1) and (2) is not due at all to the semantic content of the state. The meanings can be switched: in a different scenario, (1) can mean “Ataw has been skinny” and (2) can mean “Ataw has become fat.” As these examples show, a stative predicate with [ila] can generate both an inchoative and a universal perfect reading. With accomplishments and achievements, [ila] implies culmination of the event: the natural goal or endpoint has been reached. This is unlike another Saisiyat aspect marker, the perfective [ina], that only marks termination of the event, which can be at an arbitrary point (Puzzle Two). In (3), [ila] implies that all the rice cakes are completely eaten, i.e., the natural result has been accomplished; thus it is contradictory to state that the rice cakes have not been finished.