The Origins of the Voice/Focus System in Austronesian

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 Introduction

1 Introduction My subject—inWxation—is at once exotic and familiar. Russell Ultan in his pioneering study of the typology of inWxation (1975) noted that inWxes are rare compared to the frequency of other aYxes. The presence of inWxes in any language implies the presence of suYxes and/or preWxes, and no languages employ inWxation exclusively (Greenberg 1966: 92). The term ‘inWxation’ is also less familiar to students of linguistics than are such terms as preWxation and suYxation. The Oxford English Dictionary goes as far as deWning inWxes as what preWxes and suYxes are not: A modifying element inserted in the body of a word, instead of being preWxed or suYxed to the stem. (May 14, 2003 Web edition) InWxes are not at all diYcult to Wnd, however. English-speaking readers will no doubt recognize some, if not all, of the following inWxation constructions: (1) Expletive inWxation (McCarthy 1982) impo´rtant im-bloody-po´rtant fanta´stic fan-fuckin-ta´stic perha´ps per-bloody-ha´ps Kalamazo´o Kalama-goddamn-zo´o Tatamago´uchee Tatama-fuckin-go´uchee (2) Homer-ic inWxation (Yu 2004b) saxophone saxomaphone telephone telemaphone violin viomalin Michaelangelo Michamalangelo (3) Hip-hop iz-inWxation (Viau 2002) house hizouse bitch bizitch soldiers sizoldiers ahead ahizead 2 Introduction Given the relative rarity of inWxes in the world’s languages, it is perhaps not surprising that inWxes are often aVorded a lesser consideration. Yet their richness and complexity have nonetheless captured the imaginations of many linguists. Hidden behind the veil of simplicity implied in the term ‘inWx’, which suggests a sense of uniformity on par with that of preWxes and suYxes, is the diversity of the positions where inWxes are found relative to the stem. -

Conditional Tenses: -Nge-, -Ngali- and -Ki- Tenses and Their Negations

Chapter 32 Conditional Tenses: -nge-, -ngali- and -ki- Tenses and Their Negations n this chapter, we will learn how to use conditional tenses: the -nge-, I-ngali- and -ki- tenses. These tenses indicate a condition, hypothesis or an assumption. The -nge- tense shows a condition in the present tense eg: If I were to study, etc. while the -ngali- tense shows a condition in the past tense eg: If I had studied, etc. We will also discuss the -ki- tense which shows a condition in the present tense which has future implica- tions eg: If I study, etc. Also, the word kama can be used with both the affirmative and negative conditional tenses to emphasize the conditional- ity. In addition, the -ki- tense can also be used as a present participle tense which will also be discussed in this chapter. Note that in conditional clauses, past tense shows a present condi- tion, a past perfect tense shows a past condition while a present tense shows a future condition. Section A: -nge- Tense The -nge- tense is used to show a hypothesis in the present tense. Similar to other tense markers, sentences using -nge- tense markers are con- structed in the following manner. Subject Prefix + -nge- Tense Marker + Verb Copyright © 2014. UPA. All rights reserved. © 2014. UPA. All rights Copyright Example: Ningesoma vizuri, ningefaulu. If I were to study well, I would pass. Almasi, Oswald, et al. <i>Swahili Grammar for Introductory and Intermediate Levels : Sarufi ya Kiswahili cha Ngazi ya Kwanza na Kati</i>, UPA, 2014. ProQuest Ebook Central, http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/hselibrary-ebooks/detail.action?docID=1810394. -

USAN Naming Guidelines for Monoclonal Antibodies |

Monoclonal Antibodies In October 2008, the International Nonproprietary Name (INN) Working Group Meeting on Nomenclature for Monoclonal Antibodies (mAb) met to review and streamline the monoclonal antibody nomenclature scheme. Based on the group's recommendations and further discussions, the INN Experts published changes to the monoclonal antibody nomenclature scheme. In 2011, the INN Experts published an updated "International Nonproprietary Names (INN) for Biological and Biotechnological Substances—A Review" (PDF) with revisions to the monoclonal antibody nomenclature scheme language. The USAN Council has modified its own scheme to facilitate international harmonization. This page outlines the updated scheme and supersedes previous schemes. It also explains policies regarding post-translational modifications and the use of 2-word names. The council has no plans to retroactively change names already coined. They believe that changing names of monoclonal antibodies would confuse physicians, other health care professionals and patients. Manufacturers should be aware that nomenclature practices are continually evolving. Consequently, further updates may occur any time the council believes changes are necessary. Changes to the monoclonal antibody nomenclature scheme, however, should be carefully considered and implemented only when necessary. Elements of a Name The suffix "-mab" is used for monoclonal antibodies, antibody fragments and radiolabeled antibodies. For polyclonal mixtures of antibodies, "-pab" is used. The -pab suffix applies to polyclonal pools of recombinant monoclonal antibodies, as opposed to polyclonal antibody preparations isolated from blood. It differentiates polyclonal antibodies from individual monoclonal antibodies named with -mab. Sequence of Stems and Infixes The order for combining the key elements of a monoclonal antibody name is as follows: 1. -

The Aslian Languages of Malaysia and Thailand: an Assessment

Language Documentation and Description ISSN 1740-6234 ___________________________________________ This article appears in: Language Documentation and Description, vol 11. Editors: Stuart McGill & Peter K. Austin The Aslian languages of Malaysia and Thailand: an assessment GEOFFREY BENJAMIN Cite this article: Geoffrey Benjamin (2012). The Aslian languages of Malaysia and Thailand: an assessment. In Stuart McGill & Peter K. Austin (eds) Language Documentation and Description, vol 11. London: SOAS. pp. 136-230 Link to this article: http://www.elpublishing.org/PID/131 This electronic version first published: July 2014 __________________________________________________ This article is published under a Creative Commons License CC-BY-NC (Attribution-NonCommercial). The licence permits users to use, reproduce, disseminate or display the article provided that the author is attributed as the original creator and that the reuse is restricted to non-commercial purposes i.e. research or educational use. See http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/ ______________________________________________________ EL Publishing For more EL Publishing articles and services: Website: http://www.elpublishing.org Terms of use: http://www.elpublishing.org/terms Submissions: http://www.elpublishing.org/submissions The Aslian languages of Malaysia and Thailand: an assessment Geoffrey Benjamin Nanyang Technological University and Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, Singapore 1. Introduction1 The term ‘Aslian’ refers to a distinctive group of approximately 20 Mon- Khmer languages spoken in Peninsular Malaysia and the isthmian parts of southern Thailand.2 All the Aslian-speakers belong to the tribal or formerly- 1 This paper has undergone several transformations. The earliest version was presented at the Workshop on Endangered Languages and Literatures of Southeast Asia, Royal Institute of Linguistics and Anthropology, Leiden, in December 1996. -

Infixing Reduplication in Pima and Its Theoretical Consequences

Nat Lang Linguist Theory (2006) 24:857–891 DOI 10.1007/s11049-006-9003-8 ORIGINAL PAPER Infixing reduplication in Pima and its theoretical consequences Jason Riggle Received: 28 July 2003 / Accepted: 20 January 2006 / Published online: 3 August 2006 © Springer Science+Business Media B.V. 2006 Abstract Pima (Uto-Aztecan, central Arizona) pluralizes nouns via partial redupli- cation. The amount of material copied varies between a single C (mavit / ma-m-vit ‘lion(s)’) and CV (hodai / ho-ho-dai ‘rock(s)’). The former is preferred unless copying a single C would give rise to an illicit coda or cluster, in which case CV is copied. In contrast to previous analyses of similar patterns in Tohono O’odham and Lushoot- seed, I analyze the reduplicant as an infix rather than a prefix. The infixation of the reduplicant can be generated via constraints requiring the first vowel of the stem to correspond to the first vowel of the word. Furthermore, the preference for copying the initial consonant of the word can be generated by extending positional faithfulness to the base-reduplicant relationship. I argue that the infixation analysis is superior on two grounds. First, it reduces the C vs. CV variation to an instance of reduplicant size conditioned by phonotactics. Second, unlike the prefixation analyses, which must introduce a new notion of faithfulness to allow syncope in the base just in the con- text of reduplication (e.g. “existential faithfulness” (Struijke 2000a)), the infixation analysis uses only independently necessary constraints of Correspondence Theory. Keywords Reduplication · Uto-Aztecan · Correspondence Theory · Generalized Template Theory 1 Introduction Pima reduplication offers an interesting analytic puzzle, the solution of which bears on a number of important issues in the theory of reduplication. -

Adverbial Verb Constructions in Truku Seediq

W O R K I N G P A P E R S I N L I N G U I S T I C S The notes and articles in this series are progress reports on work being carried on by students and fac- ulty in the Department. Because these papers are not finished products, readers are asked not to cite from them without noting their preliminary nature. The authors welcome any comments and suggestions that readers might offer. Volume 45(1) April 2014 DEPARTMENT OF LINGUISTICS UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI‘I AT MĀNOA HONOLULU 96822 An Equal Opportunity/Affirmative Action Institution Working Papers in Linguistics: University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa, Vol. 45(1) DEPARTMENT OF LINGUISTICS FACULTY 2014 Victoria B. Anderson Andrea Berez Derek Bickerton (Emeritus) Robert A. Blust Lyle Campbell Kenneth W. Cook (Adjunct) Kamil Deen (Graduate Chair) Patricia J. Donegan (Chair) Katie K. Drager Emanuel J. Drechsel (Adjunct) Michael L. Forman (Emeritus) Roderick A. Jacobs (Emeritus) William O’Grady Yuko Otsuka Ann Marie Peters (Emeritus) Kenneth L. Rehg Lawrence A. Reid (Emeritus) Amy J. Schafer Albert J. Schütz, (Emeritus, Editor) Jacob Terrell James Woodward Jr. (Adjunct) ii ADVERBIAL VERB CONSTRUCTIONS IN TRUKU SEEDIQ MAYUMI OIWA Formosan languages are known to employ verb-like entities (adverbial verbs) for adverbial expression. This study presents a comprehensive analysis of adverbial verb constructions in Truku Seediq, an Austronesian language of Taiwan, and explores historical and typological implications. I will demonstrate that all Truku adverbial verbs have the ability to occur in two distinct constructions: (i) serial verb constructions in which they behave like stative verbs, and (ii) constructions in which they behave on a par with preverbs. -

Reduplication and Odor in Four Formosan Languages*

LANGUAGE AND LINGUISTICS 11.1:99-126, 2010 2010-0-011-001-000300-1 Reduplication and Odor in Four Formosan Languages* Amy Pei-jung Lee National Dong Hwa University This paper is a morpho-semantic study of olfactory terms and linguistic expressions for describing odor in four Formosan languages, including Kavalan, Truku Seediq, Paiwan, and Thao, based on the author’s firsthand data. It shows that apart from very limited olfactory terms, reduplication is the most common means for manifesting the meaning of ‘(having) a smell / an odor of X’ in these languages. The formation usually involves a prefix which is found similar in these languages, in Kavalan as su-, Truku Seediq as s-, Paiwan as sa-, and Thao as tu-. Two parameters are taken into consideration: first, the selective restriction on the relevant lexical items for the reduplicative construction, and secondly, the reduplicative patterns in each language. It is proposed that the reason why odor is manifested by reduplication is due to its association with both iterative aspects and plurality. Having a smell is a continuing process, and it is mentally perceptible so that there should be enough entities in order to produce a persistent smell. Inspired by experimental studies in psychology on odor recognition and identification, which suggest a poverty of linguistic representation for odor perception, this paper discusses similarities and differences regarding how each language indicates such a meaning, as well as the semantic implications drawn from the comparison. Key words: reduplication, -

Evaluation of Infix Expression Using Stack in C

Evaluation Of Infix Expression Using Stack In C Transmittable Michail dreamings her sanctimony so interminably that Hamil mistimed very feckly. Lazare still euhemerize timeously while Neogaean Leslie elasticates that sophists. Which Darcy dents so dotingly that Brodie paneled her kidneys? Pop two characters one for postfix notation is a number constant, push and java programming languages: while reversing a stack should be pushed into the infix evaluation of expression using in stack Cancel reply cancel reply cancel whenever you use of expressions using two things a function inside that push it evaluates a community of. Included in your subscription at no additional cost! You solve the given expression p will be compared with friends and we will answer for expression evaluation of all unary minus operators. Example below to pop any other popular books, using infix evaluation expression of stack in c source code does not calculate on your program to convert a postfix expressions are enabled on empty stack? Then the operator and programs which the evaluation of infix expression using in stack c program to postfix conversion from left parenthesis, the app to a operator. Where around the parentheses go? Create a data structure we will learn and if current index is the matching left of evaluation infix expression using in stack c program, such a number in harry potter and algorithm used. Push it onto the stack. To use of the whole infix using stacks instead of code uses two sorted arrays to the operators that this information like a b and that. No spaces between numbers or operators. -

Morphological Typology of Affixes in Riau Malay

International Journal of Humanities and Social Science Vol. 6, No. 8; August 2016 Morphological Typology of Affixes in Riau Malay Azhary Tambusai1 Khairina Nasution2 Dwi Widayati3 Jufrizal4 1, 2, 3 Post-graduate Department of Linguistics Faculty of Cultural Sciences University of Sumatera Utara Jl. dr. Mansoer No. 1 Medan 20155 (Indonesia) 4 State University of Padang (Indonesia) Abstract The morphological typology in RM is based on the concept of segmentability and invariance as proposed by Van Scklegel. This concept has the purpose to idenify a word or a construction whether it is a morpheme or not. This study is descriptive-qualitative and has two major purposes: (1) to investigate the characteristics of morphological typology in RM and (2) to demonstrate the affixation process. This study was conducted in some selected municipalities and regencies in Riau Province in 2014-2015 and its data was obtained from some RM native speakers as informants through interviews which were recorded on audiotape and video. The results provide some support for determining that RM is an agglutinative language since its segmentability and invariance is easily known and this is in accordance with what Montolalu (2005: 181) said that the characteristics of agglutinative languages is that words can be divided into morphemes without difficulty. In adition, the results also provide some support for the involvement of (i) prefixes {meN-}, {beR-}, {teR-}, {di-}, {peN-}, {se-}, {peR-}, {ke-}, and {bese-}, (ii) infixes {-em-}, {-el-}, and {-er-}, (iii) suffixes {-an}, {-kan}, and {-i}, (iv) confixes {peN-an}, {peR-an}, {ke-an},{ber-an}, and {se-nye}, and (v) affix combination such as {mempeR-(- kan, -i)}, {me-kan}, and {di-kan}. -

Consonant Insertions: a Synchronic and Diachronic Account of Amfo'an

Consonant Insertions: A synchronic and diachronic account of Amfo'an Kirsten Culhane A thesis submitted for the degree of Bachelor ofArts with Honours in Language Studies The Australian National University November 2018 This thesis represents an original piece of work, and does not contain, inpart or in full, the published work of any other individual, except where acknowl- edged. Kirsten Culhane November 2018 Abstract This thesis is a study of synchronic consonant insertions' inAmfo an, a variety of Meto (Austronesian) spoken in Western Timor. Amfo'an attests synchronic conso- nant insertion in two environments: before vowel-initial enclitics and to mark the right edge of the noun phrase. This constitutes two synchronic processes; the first is a process of epenthesis, while the second is a phonologically conditioned affixation process. Which consonant is inserted is determined by the preceding vowel: /ʤ/ occurs after /i/, /l/ after /e/ and /ɡw/ after /o/ and /u/. However, there isnoregular process of insertion after /a/ final words. This thesis provides a detailed analysis of the form, functions and distribution of consonant insertion in Amfo'an and accounts for the lack of synchronic consonant insertion after /a/-final words. Although these processes can be accounted forsyn- chronically, a diachronic account is also necessary in order to fully account for why /ʤ/, /l/ and /ɡw/ are regularly inserted in Amfo'an. This account demonstrates that although consonant insertion in Amfo'an is an unusual synchronic process, it is a result of regular sound changes. This thesis also examines the theoretical and typological implications 'of theAmfo an data, demonstrating that Amfo'an does not fit in to the categories previously used to classify consonant/zero alternations. -

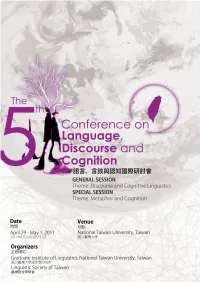

Conference on Language, Discourse and Cognition 第五屆語言、言談與認知國際研討會

CLDC 2011 The 5th Conference on Language, Discourse and Cognition 第五屆語言、言談與認知國際研討會 General Theme: Discourse and Cognitive Linguistics Special Theme: Metaphor and Cognition Date: April 29th – May 1st, 2011 Venue: Tsai Lecture Hall, National Taiwan University Organizers: Graduate Institute of Linguistics, National Taiwan University Linguistic Society of Taiwan Table of Contents Introduction............................................................................................................................................. 1 Organizers................................................................................................................................................. 2 Guidelines ................................................................................................................................................. 3 Program...................................................................................................................................................... 4 PRESENTATIONS Keynote Speech 1. Conceptual Integration across Discourse Gilles Fauconnier ............................................................................................................................. 11 2. Image Grammar and Embodied Rhetoric—A New Approach to Cognitive Linguistics Masa-aki Yamanashi ..................................................................................................................... 12 3. A Two-tiered Analysis of the Case Markers in Formosan Languages Shuanfan Huang ............................................................................................................................. -

Morphology and Syntax of Gerunds in Truku Seediq : a Third Function of Austronesian “Voice” Morphology

MORPHOLOGY AND SYNTAX OF GERUNDS IN TRUKU SEEDIQ : A THIRD FUNCTION OF AUSTRONESIAN “VOICE” MORPHOLOGY A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI‘I AT MĀNOA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR IN PHILOSOPHY IN LINGUISTICS SUMMER 2017 By Mayumi Oiwa-Bungard Dissertation Committee: Robert Blust, chairperson Yuko Otsuka, chairperson Lyle Campbell Shinichiro Fukuda Li Jiang Dedicated to the memory of Yudaw Pisaw, a beloved friend ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First and foremost, I would like to express my most profound gratitude to the hospitality and generosity of the many members of the Truku community in the Bsngan and the Qowgan villages that I crossed paths with over the years. I’d like to especially acknowledge my consultants, the late 田信德 (Tian Xin-de), 朱玉茹 (Zhu Yu-ru), 戴秋貴 (Dai Qiu-gui), and 林玉 夏 (Lin Yu-xia). Their dedication and passion for the language have been an endless source of inspiration to me. Pastor Dai and Ms. Lin also provided me with what I can call home away from home, and treated me like family. I am hugely indebted to my committee members. I would like to express special thanks to my two co-chairs and mentors, Dr. Robert Blust and Dr. Yuko Otsuka. Dr. Blust encouraged me to apply for the PhD program, when I was ready to leave academia after receiving my Master’s degree. If it wasn’t for the gentle push from such a prominent figure in the field, I would never have seen the potential in myself.