Lancini Jen-Hao Cheng [email protected]

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Rise and Fall of the Taiwan Independence Policy: Power Shift, Domestic Constraints, and Sovereignty Assertiveness (1988-2010)

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2012 The Rise and Fall of the Taiwan independence Policy: Power Shift, Domestic Constraints, and Sovereignty Assertiveness (1988-2010) Dalei Jie University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the Asian Studies Commons, and the Political Science Commons Recommended Citation Jie, Dalei, "The Rise and Fall of the Taiwan independence Policy: Power Shift, Domestic Constraints, and Sovereignty Assertiveness (1988-2010)" (2012). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 524. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/524 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/524 For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Rise and Fall of the Taiwan independence Policy: Power Shift, Domestic Constraints, and Sovereignty Assertiveness (1988-2010) Abstract How to explain the rise and fall of the Taiwan independence policy? As the Taiwan Strait is still the only conceivable scenario where a major power war can break out and Taiwan's words and deeds can significantly affect the prospect of a cross-strait military conflict, ot answer this question is not just a scholarly inquiry. I define the aiwanT independence policy as internal political moves by the Taiwanese government to establish Taiwan as a separate and sovereign political entity on the world stage. Although two existing prevailing explanations--electoral politics and shifting identity--have some merits, they are inadequate to explain policy change over the past twenty years. Instead, I argue that there is strategic rationale for Taiwan to assert a separate sovereignty. Sovereignty assertions are attempts to substitute normative power--the international consensus on the sanctity of sovereignty--for a shortfall in military- economic-diplomatic assets. -

The History and Politics of Taiwan's February 28

The History and Politics of Taiwan’s February 28 Incident, 1947- 2008 by Yen-Kuang Kuo BA, National Taiwan Univeristy, Taiwan, 1991 BA, University of Victoria, 2007 MA, University of Victoria, 2009 A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in the Department of History © Yen-Kuang Kuo, 2020 University of Victoria All rights reserved. This dissertation may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without the permission of the author. ii Supervisory Committee The History and Politics of Taiwan’s February 28 Incident, 1947- 2008 by Yen-Kuang Kuo BA, National Taiwan Univeristy, Taiwan, 1991 BA, University of Victoria, 2007 MA, University of Victoria, 2009 Supervisory Committee Dr. Zhongping Chen, Supervisor Department of History Dr. Gregory Blue, Departmental Member Department of History Dr. John Price, Departmental Member Department of History Dr. Andrew Marton, Outside Member Department of Pacific and Asian Studies iii Abstract Taiwan’s February 28 Incident happened in 1947 as a set of popular protests against the postwar policies of the Nationalist Party, and it then sparked militant actions and political struggles of Taiwanese but ended with military suppression and political persecution by the Nanjing government. The Nationalist Party first defined the Incident as a rebellion by pro-Japanese forces and communist saboteurs. As the enemy of the Nationalist Party in China’s Civil War (1946-1949), the Chinese Communist Party initially interpreted the Incident as a Taiwanese fight for political autonomy in the party’s wartime propaganda, and then reinterpreted the event as an anti-Nationalist uprising under its own leadership. -

崑 山 科 技 大 學 應 用 英 語 系 Department of Applied English Kun Shan University

崑 山 科 技 大 學 應 用 英 語 系 Department of Applied English Kun Shan University National Parks in Taiwan 臺灣的國家公園 Instructor:Yang Chi 指導老師:楊奇 Wu Hsiu-Yueh 吳秀月 Ho Chen-Shan 何鎮山 Tsai Ming-Tien 蔡茗恬 Wang Hsuan-Chi 王萱琪 Cho Ming-Te 卓明德 Hsieh Chun-Yu 謝俊昱 中華民國九十四年四月 April, 2006 Catalogue Chapter 1 Introduction ............................................................ 2 1.1 Research motivation ...................................................................................... 2 1.2 Research purpose ........................................................................................... 3 1.3 Research procedure ....................................................................................... 6 Chapter 2 Research Information ............................................. 8 2.1 Yangmingshan National Park ....................................................................... 8 2.2 Shei-Pa National Park ................................................................................. 12 2.3 Taroko National Park .................................................................................. 17 2.4 Yushan National Park .................................................................................. 20 2.5 Kenting National Park ................................................................................. 24 2.6 Kinmen National Park ................................................................................. 28 Chapter 3 Questionnarie ........................................................ 32 Chapter 4 Conclusion ............................................................ -

View, Independent Domestications of a Plant This Hypothesis Is Adopted Here, with the Standard Caveat Can Be Expected to Result in Wholly Independent Vocabularies

Rice (2011) 4:121–133 DOI 10.1007/s12284-011-9077-8 How Many Independent Rice Vocabularies in Asia? Laurent Sagart Received: 30 September 2011 /Accepted: 10 December 2011 /Published online: 5 January 2012 # Springer Science+Business Media, LLC 2011 Abstract The process of moving from collecting plants in all have the same underlying cause: the shift to agriculture the wild to cultivating and gradually domesticating them has and its demographic consequences. Populations of farmers as its linguistic corollary the formation of a specific vocab- can support larger families than hunter-gatherers, which ulary to designate the plants and their parts, the fields in gives them higher densities, and lets them expand with their which they are cultivated, the tools and activities required to genes, their crops and their languages. This is the well- cultivate them and the food preparations in which they enter. known Bellwood–Renfrew farming/language hypothesis. From this point of view, independent domestications of a plant This hypothesis is adopted here, with the standard caveat can be expected to result in wholly independent vocabularies. that not all linguistic expansions need to be agriculturally Conversely, when cultivation of a plant spreads from one based (Eskimo–Aleut an obvious case) and with the refine- population to another, one expects elements of the original ment, introduced in Bellwood (2005b) that while agriculture vocabulary to spread with cultivation practices. This paper per se will normally induce an increase in population den- examines the vocabularies of rice in Asian languages for sity, it will not by itself suffice to lead to geographical evidence of linguistic transfers, concluding that there are at expansion: another prerequisite is the possession of a diver- least two independent vocabularies of rice in Asia. -

Consonant Insertions: a Synchronic and Diachronic Account of Amfo'an

Consonant Insertions: A synchronic and diachronic account of Amfo'an Kirsten Culhane A thesis submitted for the degree of Bachelor ofArts with Honours in Language Studies The Australian National University November 2018 This thesis represents an original piece of work, and does not contain, inpart or in full, the published work of any other individual, except where acknowl- edged. Kirsten Culhane November 2018 Abstract This thesis is a study of synchronic consonant insertions' inAmfo an, a variety of Meto (Austronesian) spoken in Western Timor. Amfo'an attests synchronic conso- nant insertion in two environments: before vowel-initial enclitics and to mark the right edge of the noun phrase. This constitutes two synchronic processes; the first is a process of epenthesis, while the second is a phonologically conditioned affixation process. Which consonant is inserted is determined by the preceding vowel: /ʤ/ occurs after /i/, /l/ after /e/ and /ɡw/ after /o/ and /u/. However, there isnoregular process of insertion after /a/ final words. This thesis provides a detailed analysis of the form, functions and distribution of consonant insertion in Amfo'an and accounts for the lack of synchronic consonant insertion after /a/-final words. Although these processes can be accounted forsyn- chronically, a diachronic account is also necessary in order to fully account for why /ʤ/, /l/ and /ɡw/ are regularly inserted in Amfo'an. This account demonstrates that although consonant insertion in Amfo'an is an unusual synchronic process, it is a result of regular sound changes. This thesis also examines the theoretical and typological implications 'of theAmfo an data, demonstrating that Amfo'an does not fit in to the categories previously used to classify consonant/zero alternations. -

Understanding the Nuances of Waishengren History and Agency

China Perspectives 2010/3 | 2010 Taiwan: The Consolidation of a Democratic and Distinct Society Understanding the Nuances of Waishengren History and Agency Dominic Meng-Hsuan et Mau-Kuei Chang Édition électronique URL : http://journals.openedition.org/chinaperspectives/5310 DOI : 10.4000/chinaperspectives.5310 ISSN : 1996-4617 Éditeur Centre d'étude français sur la Chine contemporaine Édition imprimée Date de publication : 15 septembre 2010 ISSN : 2070-3449 Référence électronique Dominic Meng-Hsuan et Mau-Kuei Chang, « Understanding the Nuances of Waishengren », China Perspectives [En ligne], 2010/3 | 2010, mis en ligne le 01 septembre 2013, consulté le 28 octobre 2019. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/chinaperspectives/5310 ; DOI : 10.4000/chinaperspectives.5310 © All rights reserved Special Feature s e v Understanding the Nuances i a t c n i e of Waishengren h p s c r History and Agency e p DOMINIC MENG-HSUAN YANG AND MAU-KUEI CHANG In the late 1940s and early 50s, the world witnessed a massive wave of political migrants out of Mainland China as a result of the Chinese civil war. Those who sought refuge in Taiwan with the KMT came to be known as the “mainlanders” or “ waishengren .” This paper will provide an overview of the research on waishengren in the past few decades, outlining various approaches and highlighting specific political and social context that gave rise to these approaches. Finally, it will propose a new research agenda based on a perspective of migration studies and historical/sociological analysis. The new approach argues for the importance of both history and agency in the study of waishengren in Taiwan. -

Primary Education Kit

Primary Education Kit VISITING THE AUSTRALIAN MUSEUM BRIEFING A Museum staff member will be on hand to greet your group when you arrive. They will brief your groups about how to move around the Museum and direct you to areas of the Museum you intend to visit. BAG STORAGE There is limited bag storage available on site. It is recommended that students just bring a small carry bag with the essentials for the day, however if required, storage can be provided depending on availability. EXHIBITIONS In addition to any booked educator-led sessions, students and teachers may explore the Museum’s exhibitions in their own time. Some special exhibitions may incur an additional charge. It is suggested that students visit the galleries in small groups to prevent overcrowding. LUNCH AND BREAKS It is recommended that students bring their recess and lunch and eat in Hyde Park or Cook & Phillip Park, both of which are across the road from the Museum. Alternative arrangements will be provided in the case of wet weather. BYOD AND PHOTOGRAPHY Students are encouraged to bring their own devices to take photos, video and/or audio to record their excursion. Some temporary exhibitions do not allow photography but you will be advised of this on arrival. FREE WIFI The Museum offers free Wi-fi for onsite visitors. It is available in 30 minute sessions. Students and teachers can log on for more than one session. PHOTOCOPYING Please photocopy the following materials for students and accompanying adults prior to your visit. SUPERVISION Teachers and supervising adults are required to stay with their groups at all times. -

The Taiwan Issue in China-Europe Relations” Shanghai, China September 21-22, 2015

12th Annual Conference on “The Taiwan Issue in China-Europe Relations” Shanghai, China September 21-22, 2015 A workshop jointly organised by the German Institute for International and Security Affairs / Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik (SWP), Berlin and the Shanghai Institutes for International Studies (SIIS), Shanghai. With friendly support of the Friedrich-Ebert- Stiftung (Shanghai Office). Discussion Paper Do not cite or quote without author’s permission New Characteristics of Future Cross-Straits Relations and New Challenges Hu Lingwei Shanghai East Asia Institute New Characteristics of Future Cross-Straits Relations and New Challenges Hu Lingwei In recent years, as seen from the course of observing the Taiwan Straits’ situation, on the one hand, social activities in Taiwan were very active, and many people, especially the young generation, expressed opinions on some topics, and actively participated in social and political life, not only impacting Taiwan’s political situation, but also exerting profound influence on cross-Straits relations; on the other hand, under the joint influence of the mainland, Taiwan and international factors, the cross-Straits relations and Taiwan Straits’ situation maintained a steady trend of development. Through analyzing and studying the current and future cross-Straits relations, we can see that though cross-Straits relations have encountered some new complicated situations emerging in Taiwan’s society, overall cross-Straits relations have maintained the momentum of steady development and shown new characteristics. In view of the new characteristics manifested by cross-Straits relations, actively and properly handling new problems facing future cross-Straits relations is conducive to promoting and maintaining the trend of steady development of cross-Straits relations. -

Gender and the Housing “Questions” in Taiwan

Gender and the Housing “Questions” in Taiwan Yi-Ling Chen Associate Professor Global and Area Studies/ Geography University of Wyoming [email protected] Abstract This paper argues that the housing system is not only capitalist but also patriarchal by analyzing how the interrelations of the state, housing market, and the family reproduce gender divisions. In contrast to the housing condition of the working class in pre-welfare state Europe, as originally described by Friedrich Engels, Taiwan’s housing system was constructed by an authoritarian developmental state that repressed labor movements and emphasized economic development over social welfare. However, since the late 1980s, pro-market housing policies have greatly enhanced the commodification of housing, resulting in a unique combination of high homeownership rates, high vacancy rates, and high housing prices. This paper examines the formation of housing questions in Taiwan and its impact on women. In doing so it reveals how a social housing movement emerged in the context of a recent housing boom – on that that has occurred despite a global economic downturn – and which could provide an opportunity for feminist intervention within the housing system to transform gender relations. Published with Creative Commons licence: Attribution–Noncommercial–No Derivatives Gender and the Housing “Questions” in Taiwan 640 Introduction Housing prices in Taiwan have nearly doubled since the most recent housing boom, which began in 2005. This escalation has led to a strong social housing movement for renters, beginning in Taiwan in 2010. Social rental housing itself is a new idea, because most of the government-constructed housing has been sold to the buyers at subsidized prices, so the number of available social rental properties remains extremely small: with only about 0.08 percent of the housing stock qualifying as social rental housing. -

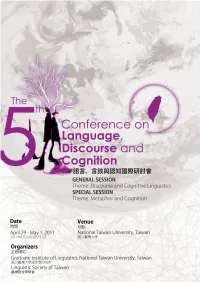

Conference on Language, Discourse and Cognition 第五屆語言、言談與認知國際研討會

CLDC 2011 The 5th Conference on Language, Discourse and Cognition 第五屆語言、言談與認知國際研討會 General Theme: Discourse and Cognitive Linguistics Special Theme: Metaphor and Cognition Date: April 29th – May 1st, 2011 Venue: Tsai Lecture Hall, National Taiwan University Organizers: Graduate Institute of Linguistics, National Taiwan University Linguistic Society of Taiwan Table of Contents Introduction............................................................................................................................................. 1 Organizers................................................................................................................................................. 2 Guidelines ................................................................................................................................................. 3 Program...................................................................................................................................................... 4 PRESENTATIONS Keynote Speech 1. Conceptual Integration across Discourse Gilles Fauconnier ............................................................................................................................. 11 2. Image Grammar and Embodied Rhetoric—A New Approach to Cognitive Linguistics Masa-aki Yamanashi ..................................................................................................................... 12 3. A Two-tiered Analysis of the Case Markers in Formosan Languages Shuanfan Huang ............................................................................................................................. -

Building Panethnic Coalitions in Asian American, Native Hawaiian And

Building Panethnic Coalitions in Asian American, Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander Communities: Opportunities & Challenges This paper is one in a series of evaluation products emerging states around the country were supported through this pro- from Social Policy Research Associates’ evaluation of Health gram, with the Asian & Pacific Islander American Health Forum Through Action (HTA), a $16.5 million, four-year W.K. Kellogg serving as the national advocacy partner and technical assis- Foundation supported initiative to reduce disparities and tance hub. advance healthy outcomes for Asian American, Native Hawai- Each of the HTA partners listed below have made mean- ian, and Pacific Islander (AA and NHPI) children and families. ingful inroads towards strengthening local community capacity A core HTA strategy is the Community Partnerships Grant to address disparities facing AA and NHPIs, as well as sparked Program, a multi-year national grant program designed to a broader national movement for AA and NHPI health. The strengthen and bolster community approaches to improv- voices of HTA partners – their many accomplishments, moving ing the health of vulnerable AA and NHPIs. Ultimately, seven stories, and rich lessons learned from their experience – serve AA and NHPI collaboratives and 11 anchor organizations in 15 as the basis of our evaluation. National Advocacy Partner HTA Organizational Partners Asian & Pacific Islander American Health Forum – West Michigan Asian American Association – Asian Pacific American Network of Oregon HTA Regional -

BOOK of ABSTRACTS June 28 to July 2, 2021 15Th ICAL 2021 WELCOME

15TH INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON AUSTRONESIAN LINGUISTICS BOOK OF ABSTRACTS June 28 to July 2, 2021 15th ICAL 2021 WELCOME The Austronesian languages are a family of languages widely dispersed throughout the islands of The name Austronesian comes from Latin auster ICAL The 15-ICAL wan, Philippines 15th ICAL 2021 ORGANIZERS Department of Asian Studies Sinophone Borderlands CONTACTS: [email protected] [email protected] 15th ICAL 2021 PROGRAMME Monday, June 28 8:30–9:00 WELCOME 9:00–10:00 EARLY CAREER PLENARY | Victoria Chen et al | CHANNEL 1 Is Malayo-Polynesian a primary branch of Austronesian? A view from morphosyntax 10:00–10:30 COFFEE BREAK | CHANNEL 3 CHANNEL 1 CHANNEL 2 S2: S1: 10:30-11:00 Owen Edwards and Charles Grimes Yoshimi Miyake A preliminary description of Belitung Malay languages of eastern Indonesia and Timor-Leste Atsuko Kanda Utsumi and Sri Budi Lestari 11:00-11:30 Luis Ximenes Santos Language Use and Language Attitude of Kemak dialects in Timor-Leste Ethnic groups in Indonesia 11:30-11:30 Yunus Sulistyono Kristina Gallego Linking oral history and historical linguistics: Reconstructing population dynamics, The case of Alorese in east Indonesia agentivity, and dominance: 150 years of language contact and change in Babuyan Claro, Philippines 12:00–12:30 COFFEE BREAK | CHANNEL 3 12:30–13:30 PLENARY | Olinda Lucas and Catharina Williams-van Klinken | CHANNEL 1 Modern poetry in Tetun Dili CHANNEL 1 CHANNEL