Diplomarbeit Waltraud WOLFMAYR

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Songs About Joni

Songs About Joni Compiled by: Simon Montgomery, © 2003 Latest Update: Dec. 28, 2020 Please send comments, corrections or additions to: [email protected] © Ed Thrasher, March 1968 Song Title Musician Album / CD Title 1967 Lady Of Rohan Chuck Mitchell Unreleased 1969 Song To A Cactus Tree Graham Nash Unreleased Why, Baby Why Graham Nash Unreleased Guinnevere Crosby, Stills & Nash Crosby, Stills & Nash Pre-Road Downs Crosby, Stills & Nash Crosby, Stills & Nash Portrait Of The Lady As A Young Artist Seatrain Seatrain (Debut LP) 1970 Only Love Can Break Your Heart Neil Young After The Goldrush Our House Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young Déjà Vu 1971 Just Joni Mitchell Charles John Quarto Unreleased Better Days Graham Nash Songs For Beginners I Used To Be A King Graham Nash Songs For Beginners Simple Man Graham Nash Songs For Beginners Love Has Brought Me Around James Taylor Mudslide Slim & The Blue Horizon You Can Close Your Eyes James Taylor Mudslide Slim & The Blue Horizon 1972 New Tune James Taylor One Man Dog 1973 It's Been A Long Time Eric Andersen Stages: The Lost Album You'’ll Never Be The Same Graham Nash Wild Tales Song For Joni Dave Van Ronk songs for ageing children Sweet Joni Neil Young Unreleased Concert Recording 1975 She Lays It On The Line Ronee Blakley Welcome Mama Lion David Crosby / Graham Nash Wind On The Water 1976 I Used To Be A King David Crosby / Graham Nash Crosby-Nash LIVE Simple Man David Crosby / Graham Nash Crosby-Nash LIVE Mama Lion David Crosby / Graham Nash Crosby-Nash LIVE Song For Joni Denise Kaufmann Dream Flight Mellow -

Stephanie Orfano Is the Social Science Librarian at the Downtown Oshawa Branch of the University of Ontario Institute of Technology (UOIT)

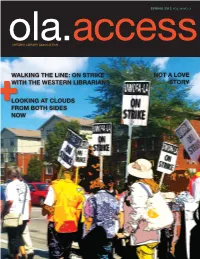

SPRING 2012 vol.18 no. 2 ola.ontario library association access WALKING THE LINE: ON STRIKE NOT A LOVE WITH THE WESTERN LIBRARIANS STORY LOOKING AT CLOUDS FROM BOTH SIDES NOW PrintOLA_Access18.2Spring2012FinalDraft.indd 1 12-03-31 1:11 PM Call today to request your Free catalogue! • Library Supplies • Computer Furniture • Office Furniture • Library Shelving • Book & Media Display • Reading Promotions • Early Learning • Book Trucks • Archival Supplies Call • 1.800.268.2123 Fax • 1.800.871.2397 Shop Online • www.carrmclean.ca PrintOLA_Access18.2Spring2012FinalDraft.indd 2 12-03-31 1:11 PM spring 2012 18:2 contents Features Call today to request Features your Free 11 Risk, Solidarity, Value 21 La place de la bibliothèque publique dans la catalogue! by Kristin hoffmann culture franco-ontarienne During the recent strike by librarians at the University of par steven Kraus Western Ontario, Kristin Hoffmann learned a lot about Vive les bibliothèques publiques du Grand Nord! Steven • Library Supplies her profession, her colleagues and herself. Kraus fait témoignage du rôle que joue la bibliothèque publique dans la promotion de la francophonie. • Computer Furniture 14 Not a Love Story by lisa sloniowsKi 22 Cloudbusting Creating an archive of feminist pornography raises by nicK ruest & john finK • Office Furniture many questions about libraries, librarians, our values and Is all this "cloud" hype ruining your sunny day? Nick • Library Shelving our responsibilities. Lisa Sloniowski guides us through this Ruest and John Fink clear the air and make it all right. The controversial area. forecast is good. • Book & Media Display 18 Visualizing Your Research 24 Governance 101: CEO Evaluation by jenny marvin by jane HILTON • Reading Promotions GeoPortal from Scholars Portal won this year's OLITA As our series on governance continues, Jane Hilton focuses Award for Technological Innovation. -

Seriously Playful and Playfully Serious: the Helpfulness of Humorous Parody Michael Richard Lucas Clemson University

Clemson University TigerPrints All Dissertations Dissertations 5-2015 Seriously Playful and Playfully Serious: The Helpfulness of Humorous Parody Michael Richard Lucas Clemson University Follow this and additional works at: https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_dissertations Recommended Citation Lucas, Michael Richard, "Seriously Playful and Playfully Serious: The eH lpfulness of Humorous Parody" (2015). All Dissertations. 1486. https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_dissertations/1486 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Dissertations at TigerPrints. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Dissertations by an authorized administrator of TigerPrints. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SERIOUSLY PLAYFUL AND PLAYFULLY SERIOUS: THE HELPFULNESS OF HUMOROUS PARODY A Dissertation Presented to the Graduate School of Clemson University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy Rhetorics, Communication, and Information Design by Michael Richard Lucas May 2014 Accepted by: Victor J. Vitanza, Committee Chair Stephaine Barczewski Cynthia Haynes Beth Lauritis i ABSTRACT In the following work I create and define the parameters for a specific form of humorous parody. I highlight specific problematic narrative figures that circulate the public sphere and reinforce our serious narrative expectations. However, I demonstrate how critical public pedagogies are able to disrupt these problematic narrative expectations. Humorous parodic narratives are especially equipped to help us in such situations when they work as a critical public/classroom pedagogy, a form of critical rhetoric, and a form of mass narrative therapy. These findings are supported by a rhetorical analysis of these parodic narratives, as I expand upon their ability to provide a practical model for how to create/analyze narratives both inside/outside of the classroom. -

The Songs Songs That Mention Joni (Or One of Her Songs)

Inspired by Joni - the Songs Songs That Mention Joni (or one of her songs) Compiled by: Simon Montgomery, © 2003 Latest Update: May 15, 2021 Please send comments, corrections or additions to: [email protected] © Ed Thrasher, March 1968 Song Title Musician Album / CD Title 1968 Scorpio Lynn Miles Dancing Alone - Songs Of William Hawkins 1969 Spinning Wheel Blood, Sweat, and Tears Blood, Sweat, and Tears 1971 Billy The Mountain Frank Zappa / The Mothers Just Another Band From L.A. Going To California Led Zeppelin Led Zeppelin IV Going To California Led Zeppelin BBC Sessions 1972 Somebody Beautiful Just Undid Me Peter Allen Tenterfield Saddler Thoughts Have Turned Flo & Eddie The Phlorescent Leech & Eddie Going To California (Live) Led Zeppelin How The West Was Won 1973 Funny That Way Melissa Manchester Home To Myself You Put Me Thru Hell Original Cast The Best Of The National Lampoon Radio Hour (Joni Mitchell Parody) If We Only Had The Time Flo & Eddie Flo & Eddie 1974 Kama Sutra Time Flo & Eddie Illegal, Immoral & Fattening The Best Of My Love Eagles On The Border 1975 Tangled Up In Blue Bob Dylan Blood On The Tracks Uncle Sea-Bird Pete Atkin Live Libel Joni Eric Kloss Bodies' Warmth Passarela Nana Caymmi Ponta De Areia 1976 Superstar Paul Davis Southern Tracks & Fantasies If You Donít Like Hank Williams Kris Kristofferson Surreal Thing Makes Me Think of You Sandy Denny The Attic Tracks Vol. 4: Together Again Turntable Lady Curtis & Wargo 7" 45rpm Single 1978 So Blue Stan Rogers Turnaround Happy Birthday (to Joni Mitchell) Dr. John Period On Horizon 1979 (We Are) The Nowtones Blotto Hello! My Name Is Blotto. -

Rolling Stone Magazine's Top 500 Songs

Rolling Stone Magazine's Top 500 Songs No. Interpret Title Year of release 1. Bob Dylan Like a Rolling Stone 1961 2. The Rolling Stones Satisfaction 1965 3. John Lennon Imagine 1971 4. Marvin Gaye What’s Going on 1971 5. Aretha Franklin Respect 1967 6. The Beach Boys Good Vibrations 1966 7. Chuck Berry Johnny B. Goode 1958 8. The Beatles Hey Jude 1968 9. Nirvana Smells Like Teen Spirit 1991 10. Ray Charles What'd I Say (part 1&2) 1959 11. The Who My Generation 1965 12. Sam Cooke A Change is Gonna Come 1964 13. The Beatles Yesterday 1965 14. Bob Dylan Blowin' in the Wind 1963 15. The Clash London Calling 1980 16. The Beatles I Want zo Hold Your Hand 1963 17. Jimmy Hendrix Purple Haze 1967 18. Chuck Berry Maybellene 1955 19. Elvis Presley Hound Dog 1956 20. The Beatles Let It Be 1970 21. Bruce Springsteen Born to Run 1975 22. The Ronettes Be My Baby 1963 23. The Beatles In my Life 1965 24. The Impressions People Get Ready 1965 25. The Beach Boys God Only Knows 1966 26. The Beatles A day in a life 1967 27. Derek and the Dominos Layla 1970 28. Otis Redding Sitting on the Dock of the Bay 1968 29. The Beatles Help 1965 30. Johnny Cash I Walk the Line 1956 31. Led Zeppelin Stairway to Heaven 1971 32. The Rolling Stones Sympathy for the Devil 1968 33. Tina Turner River Deep - Mountain High 1966 34. The Righteous Brothers You've Lost that Lovin' Feelin' 1964 35. -

Court Green: Dossier: Political Poetry Columbia College Chicago

Columbia College Chicago Digital Commons @ Columbia College Chicago Court Green Publications 3-1-2007 Court Green: Dossier: Political Poetry Columbia College Chicago Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.colum.edu/courtgreen Part of the Poetry Commons This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. Recommended Citation Columbia College Chicago, "Court Green: Dossier: Political Poetry" (2007). Court Green. 4. https://digitalcommons.colum.edu/courtgreen/4 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Publications at Digital Commons @ Columbia College Chicago. It has been accepted for inclusion in Court Green by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Columbia College Chicago. For more information, please contact [email protected]. court green 4 Court Green is published annually at Columbia College Chicago Court Green Editors: Arielle Greenberg, Tony Trigilio, and David Trinidad Managing Editor: Cora Jacobs Editorial Assistants: Ian Harris and Brandi Homan Court Green is published annually in association with the English Department of Columbia College Chicago. Our thanks to Ken Daley, Chair of the English Department; Dominic Pacyga, Interim Dean of Liberal Arts and Sciences; Steven Kapelke, Provost; and Dr. Warrick Carter, President of Columbia College Chicago. “The Late War”, from The Complete Poems of D.H. Lawrence by D.H. Lawrence, edited by V. de Sola Pinto & F. W. Roberts, copyright © 1964, 1971 by Angelo Ravagli and C. M. Weekley, Executors of the Estate of Frieda Lawrence Ravagli. Used by permission of Viking Penguin, a division of Penguin Group (USA) Inc. “In America” by Bernadette Mayer is reprinted from United Artists (No. -

012521-DRAFT-Bothsidesnow

Both Sides Now: Singer-Songwriters Then and Now An Etz Chayim Fifth Friday SHABBAT SERVICE Kabbalat Shabbat • Happy • Shower the People You Love With Love L’Cha Dodi (to Sweet Baby James) Bar’chu • Creation: Big Yellow Taxi • Revelation: I Choose Y0u Sh’ma • Both Sides Now + Traditional Prayer • V’ahavta: All Of Me • Redemption: Brave Hashkiveynu / Lay Us Down: Beautiful Amidah (“Avodah” / Service) • Avot v’Imahot: Abraham’s Daughter • G’vurot: Music To My Eyes • K’dushat haShem: Edge Of Glory • R’Tzeih: Chelsea Morning • Modim: The Secret Of LIfe • Shalom: Make You Feel My Love (instrumental & reflection) D’Var Torah • Miriam’s Song Congregation Etz Chayim Healing Prayer: You’ve Got a Friend Palo Alto, CA Aleynu Rabbi Chaim Koritzinsky Mourners’ Kaddish: Fire And Rain + Traditional Prayer Birchot Hamishpachah / Parents Bless their Children: Circle Game + Inclusive Blessing of Children Closing Song: Adon Olam (to Hallelujah) Both Sides Now Shabbat, 1/29/21 • Shabbat Evening Service, page 1 Kavannah for Our Service For this Fifth Friday Shabbat service we will experience songs by a diverse array of singer- songwriters in place of many of our traditional prayers. The intent is to lift up the prayers by viewing them through a new lens, and perhaps gain new insight into beloved, contemporary songs, whether familiar or new to us. “Both Sides Now” speaks to several relevant themes in our service and in our hearts: • This week’s Torah portion, B’Shallah, begins with our Israeilite ancestors in slavery, on one side of the Sea of Reeds and ends with them as a newly freed people on the other side. -

Magnum Moon-- Naturally--In the Arkansas Derby

SUNDAY, APRIL 15, 2018 MAGNUM MOON-- FAMED SPORTSWRITER BILL NACK DEAD AT 77 By Bill Finley NATURALLY--IN THE Bill Nack, widely recognized as one of the most talented racing writers of all time, passed away Friday at his home in ARKANSAS DERBY Washington D.C. Nack died following a bout with cancer. He was 77. Best known for his work with Sports Illustrated, where he was employed from 1978 to 2001, Nack covered many sports, but racing was his primary assignment and his first love. His 1990 story Pure Heart on the passing of Secretariat was chosen as one of SI=s 60 most iconic stories. His 1975 book on Secretariat, ASecretariat : The Making of a Champion@ is considered the definitive book on the 1973 Triple Crown winner. ABill was a great reporter, a great writer a great friend, a great colleague,@ said Steve Crist, the former racing writer for the New York Times who later became the publisher of the Daily Racing Form. AHis work on Secretariat was the best turf writing ever done.@ Cont. p11 IN TDN EUROPE TODAY Magnum Moon | Coady photography WINX TIES BLACK CAVIAR’S WIN RECORD Trainer Todd Pletcher entered Saturday=s GI Arkansas Derby Winx (Aus) (Street Cry {Ire}) saluted in her 25th consecutive race, having saddled back-to-back winners of the race in the form of tying Black Caviar (Aus) (Bel Esprit {Aus})’s win record, when Overanalyze (Dixie Union) and Danza (Street Boss) in 2013 and scoring in her second G1 Queen Elizabeth S. at Royal Randwick on 2014, respectively. -

Joni Mitchell," 1966-74

"All Pink and Clean and Full of Wonder?" Gendering "Joni Mitchell," 1966-74 Stuart Henderson Just before our love got lost you said: "I am as constant as a northern star." And I said: "Constantly in the darkness - Where 5 that at? Ifyou want me I'll be in the bar. " - "A Case of You," 1971 Joni Mitchell has always been difficult to categorize. A folksinger, a poet, a wife, a Canadian, a mother, a party girl, a rock star, a hermit, a jazz singer, a hippie, a painter: any or all of these descriptions could apply at any given time. Moreover, her musicianship, at once reminiscent of jazz, folk, blues, rock 'n' roll, even torch songs, has never lent itself to easy categorization. Through each successive stage of her career, her songwriting has grown ever more sincere and ever less predictable; she has, at every turn, re-figured her public persona, belied expectations, confounded those fans and critics who thought they knew who she was. And it has always been precisely here, between observers' expec- tations and her performance, that we find contested terrain. At stake in the late 1960s and early 1970s was the central concern for both the artist and her audience that "Joni Mitchell" was a stable identity which could be categorized, recognized, and understood. What came across as insta- bility to her fans and observers was born of Mitchell's view that the honest reflection of growth and transformation is the basic necessity of artistic expres- sion. As she explained in 1979: You have two options. -

1978-05-22 P MACHO MAN Village People RCA 7" Vinyl Single 103106 1978-05-22 P MORE LIKE in the MOVIES Dr

1978-05-22 P MACHO MAN Village People RCA 7" vinyl single 103106 1978-05-22 P MORE LIKE IN THE MOVIES Dr. Hook EMI 7" vinyl single CP 11706 1978-05-22 P COUNT ON ME Jefferson Starship RCA 7" vinyl single 103070 1978-05-22 P THE STRANGER Billy Joel CBS 7" vinyl single BA 222406 1978-05-22 P YANKEE DOODLE DANDY Paul Jabara AST 7" vinyl single NB 005 1978-05-22 P BABY HOLD ON Eddie Money CBS 7" vinyl single BA 222383 1978-05-22 P RIVERS OF BABYLON Boney M WEA 7" vinyl single 45-1872 1978-05-22 P WEREWOLVES OF LONDON Warren Zevon WEA 7" vinyl single E 45472 1978-05-22 P BAT OUT OF HELL Meat Loaf CBS 7" vinyl single ES 280 1978-05-22 P THIS TIME I'M IN IT FOR LOVE Player POL 7" vinyl single 6078 902 1978-05-22 P TWO DOORS DOWN Dolly Parton RCA 7" vinyl single 103100 1978-05-22 P MR. BLUE SKY Electric Light Orchestra (ELO) FES 7" vinyl single K 7039 1978-05-22 P HEY LORD, DON'T ASK ME QUESTIONS Graham Parker & the Rumour POL 7" vinyl single 6059 199 1978-05-22 P DUST IN THE WIND Kansas CBS 7" vinyl single ES 278 1978-05-22 P SORRY, I'M A LADY Baccara RCA 7" vinyl single 102991 1978-05-22 P WORDS ARE NOT ENOUGH Jon English POL 7" vinyl single 2079 121 1978-05-22 P I WAS ONLY JOKING Rod Stewart WEA 7" vinyl single WB 6865 1978-05-22 P MATCHSTALK MEN AND MATCHTALK CATS AND DOGS Brian and Michael AST 7" vinyl single AP 1961 1978-05-22 P IT'S SO EASY Linda Ronstadt WEA 7" vinyl single EF 90042 1978-05-22 P HERE AM I Bonnie Tyler RCA 7" vinyl single 1031126 1978-05-22 P IMAGINATION Marcia Hines POL 7" vinyl single MS 513 1978-05-29 P BBBBBBBBBBBBBOOGIE -

The Modality of Miles Davis and John Coltrane14

CURRENT A HEAD ■ 371 MILES DAVIS so what JOHN COLTRANE giant steps JOHN COLTRANE acknowledgement MILES DAVIS e.s.p. THE MODALITY OF MILES DAVIS AND JOHN COLTRANE14 ■ THE SORCERER: MILES DAVIS (1926–1991) We have encountered Miles Davis in earlier chapters, and will again in later ones. No one looms larger in the postwar era, in part because no one had a greater capacity for change. Davis was no chameleon, adapting himself to the latest trends. His innovations, signaling what he called “new directions,” changed the ground rules of jazz at least fi ve times in the years of his greatest impact, 1949–69. ■ In 1949–50, Davis’s “birth of the cool” sessions (see Chapter 12) helped to focus the attentions of a young generation of musicians looking beyond bebop, and launched the cool jazz movement. ■ In 1954, his recording of “Walkin’” acted as an antidote to cool jazz’s increasing deli- cacy and reliance on classical music, and provided an impetus for the development of hard bop. ■ From 1957 to 1960, Davis’s three major collaborations with Gil Evans enlarged the scope of jazz composition, big-band music, and recording projects, projecting a deep, meditative mood that was new in jazz. At twenty-three, Miles Davis had served a rigorous apprenticeship with Charlie Parker and was now (1949) about to launch the cool jazz © HERMAN LEONARD PHOTOGRAPHY LLC/CTS IMAGES.COM movement with his nonet. wwnorton.com/studyspace 371 7455_e14_p370-401.indd 371 11/24/08 3:35:58 PM 372 ■ CHAPTER 14 THE MODALITY OF MILES DAVIS AND JOHN COLTRANE ■ In 1959, Kind of Blue, the culmination of Davis’s experiments with modal improvisation, transformed jazz performance, replacing bebop’s harmonic complexity with a style that favored melody and nuance. -

Blankg5 Copy 7/1/11 3:56 PM Page 208 5Gerry:Blankg5 Copy 7/1/11 3:56 PM Page 209

5gerry:blankG5 copy 7/1/11 3:56 PM Page 208 5gerry:blankG5 copy 7/1/11 3:56 PM Page 209 TOM GERRY “I Sing My Sorrow and I Paint My Joy”: Joni Mitchell’s Songs and Images ONI MITCHELL is best known as a musician. She is a popular music superstar, and has been since the early 1970s. Surprisingly, considering Mitchell’s Jstatus in the music world, she has often said that for her, painting is primary, music and writing secondary. Regarding Mingus, her 1979 jazz album, she commented that with it she “was trying to become the Jackson Pollock of music.” In a 1998 interview Mitchell reflected, “I think of myself as a painter who writes music.”1 In our era, when many critics and philosophers view interarts relationships with suspicion, it is remarkable that Mitchell persists so vigorously in creating work that involves multiple arts. To consider Mitchell’s art as the productions of a multi-talented person does not get us far with the works themselves, since this approach immediately invokes the abstractions and speculations of psychology. On the other hand, postmodernism has taught us that there is no absolute, tran- scendent meaning available as content for various forms. In the face of such strong objections to coalescing arts, Mitchell insists through her works that her art is intrinsically multidisciplinary and needs to be understood as such. Interarts relationships have been studied at least since Aristotle decreed that the lexis, the words, takes precedence over the opsis, the spectacle, of drama. Although recognized as being distinct, the arts have also commonly been discussed as though they are analogous.