The “Second Quintet”: Miles Davis, the Jazz Avant-Garde, and Change, 1959-68

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Seeing (For) Miles: Jazz, Race, and Objects of Performance

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 2014 Seeing (for) Miles: Jazz, Race, and Objects of Performance Benjamin Park anderson College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the African American Studies Commons, and the American Studies Commons Recommended Citation anderson, Benjamin Park, "Seeing (for) Miles: Jazz, Race, and Objects of Performance" (2014). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539623644. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-t267-zy28 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Seeing (for) Miles: Jazz, Race, and Objects of Performance Benjamin Park Anderson Richmond, Virginia Master of Arts, College of William and Mary, 2005 Bachelor of Arts, Virginia Commonwealth University, 2001 A Dissertation presented to the Graduate Faculty of the College of William and Mary in Candidacy for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy American Studies Program College of William and Mary May 2014 APPROVAL PAGE This Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Benjamin Park Anderson Approved by T7 Associate Professor ur Knight, American Studies Program The College -

Juilliard Jazz Ensembles

The Juilliard School Presents Juilliard Jazz Ensembles Monday, January 29, 2018, 7:30pm Paul Hall The Music of Miles Davis Wynton Marsalis, Guest Coach Dizzy Gillespie Ensemble Swing Spring (Miles Davis, arr. Joel Wenhardt) Flamenco Sketches (Miles Davis and Bill Evans, arr.Andrea Domenici) Nardis (Miles Davis, arr. Jeffery Miller) Paraphernalia (Wayne Shorter, arr. Adam Olszewski) Half Nelson (Miles Davis, arr. David Milazzo) David Milazzo, Alto Saxophone Anthony Hervey, Trumpet Jeffery Miller, Trombone Andrea Domenici, Piano Joel Wenhardt, Piano Adam Olszewski, Bass Cameron MacIntosh, Drums Elio Villafranca, Resident Coach Intermission (Program continues) Juilliard gratefully acknowledges the Talented Students in the Arts Initiative, a collaboration for the Doris Duke Charitable Foundation and the Surdna Foundation, for their generous support of Juilliard Jazz. Major funding for establishing Paul Recital Hall and for continuing access to its series of public programs has been granted by The Bay Foundation and the Josephine Bay Paul and C. Michael Paul Foundation in memory of Josephine Bay Paul. Please make certain that all electronic devices are turned off during the performance. The taking of photographs and the use of recording equipment are not permitted in this auditorium. 1 The Dave Brubeck Ensemble Dig (Miles Davis, arr. Dave Brubeck Ensemble) Fall (Wayne Shorter, arr. Dave Brubeck Ensemble) Milestones (Miles Davis, arr. Dave Brubeck Ensemble) Circle (Miles Davis, arr. Dave Brubeck Ensemble) So Near, So Far (Tony Crombie and Bennie Green, arr. Dave Brubeck Ensemble) Zoe Obadia, Alto Saxophone Noah Halpern, Trumpet Jasim Perales, Trombone Joseph Block, Piano Isaiah Thompson, Piano Adam Olszewski, Bass Francesco Ciniglio, Drums Helen Sung, Resident Coach Program order and selections are subject to change. -

Mike Mangini

/.%/&4(2%% 02):%3&2/- -".#0'(0%4$)3*4"%-&34&55*/(4*()54 7). 9!-!(!$25-3 VALUED ATOVER -ARCH 4HE7ORLDS$RUM-AGAZINE 0/5)& '0$64)*)"5 "$)*&7&5)&$-"44*$ 48*/(406/% "35#-",&: 5)&.&/503 50%%46$)&3."/ 45:-&"/%"/"-:4*4 $2%!-4(%!4%23 Ê / Ê" Ê," Ê/"Ê"6 , /Ê-1 -- (3&(03:)65$)*/40/ 8)&3&+";;41"45"/%'6563&.&&5 #6*-%:06308/ .6-5*1&%"-4&561 -ODERN$RUMMERCOM 3&7*&8&% 5"."4*-7&345"33&.0108&34530,&130-6%8*("5-"4130)"3%8"3&3*.4)05-0$."55/0-"/$:.#"-4 Volume 36, Number 3 • Cover photo by Paul La Raia CONTENTS Paul La Raia Courtesy of Mapex 40 SETTING SIGHTS: CHRIS ADLER Lamb of God’s tireless sticksman embraces his natural lefty tendencies. by Ken Micallef Timothy Saccenti 54 MIKE MANGINI By creating layers of complex rhythms that complement Dream Theater’s epic arrangements, “the new guy” is ushering in a bold and exciting era for the band, its fans, and progressive rock music itself. by Mike Haid 44 GREGORY HUTCHINSON Hutch might just be the jazz drummer’s jazz drummer— historically astute and futuristically minded, with the kind 12 UPDATE of technique, soul, and sophistication that today’s most important artists treasure. • Manraze’s PAUL COOK by Ken Micallef • Jazz Vet JOEL TAYLOR • NRBQ’s CONRAD CHOUCROUN • Rebel Rocker HANK WILLIAMS III Chuck Parker 32 SHOP TALK Create a Stable Multi-Pedal Setup 36 PORTRAITS NYC Pocket Master TONY MASON 98 WHAT DO YOU KNOW ABOUT...? Faust’s WERNER “ZAPPI” DIERMAIER One of Three Incredible 70 INFLUENCES: ART BLAKEY Prizes From Yamaha Drums Enter to Win We all know those iconic black-and-white images: Blakey at the Valued $ kit, sweat beads on his forehead, a flash in the eyes, and that at Over 5,700 pg 85 mouth agape—sometimes with the tongue flat out—in pure elation. -

December 1992

VOLUME 16, NUMBER 12 MASTERS OF THE FEATURES FREE UNIVERSE NICKO Avant-garde drummers Ed Blackwell, Rashied Ali, Andrew JEFF PORCARO: McBRAIN Cyrille, and Milford Graves have secured a place in music history A SPECIAL TRIBUTE Iron Maiden's Nicko McBrain may by stretching the accepted role of When so respected and admired be cited as an early influence by drums and rhythm. Yet amongst a player as Jeff Porcaro passes metal drummers all over, but that the chaos, there's always been away prematurely, the doesn't mean he isn't as vital a play- great discipline and thought. music—and our lives—are never er as ever. In this exclusive interview, Learn how these free the same. In this tribute, friends find out how Nicko's drumming masters and admirers share their fond gears move, and what's tore down the walls. memories of Jeff, and up with Maiden's power- • by Bill Milkowski 32 remind us of his deep ful new album and tour. 28 contributions to our • by Teri Saccone art. 22 • by Robyn Flans THE PERCUSSIVE ARTS SOCIETY For thirty years the Percussive Arts Society has fostered credibility, exposure, and the exchange of ideas for percus- sionists of every stripe. In this special report, learn where the PAS has been, where it is, and where it's going. • by Rick Mattingly 36 MD TRIVIA CONTEST Win a Sonor Force 1000 drumkit—plus other great Sonor prizes! 68 COVER PHOTO BY MICHAEL BLOOM Education 58 ROCK 'N' JAZZ CLINIC Back To The Dregs BY ROD MORGENSTEIN Equipment Departments 66 BASICS 42 PRODUCT The Teacher Fallacy News BY FRANK MAY CLOSE-UP 4 EDITOR'S New Sabian Products OVERVIEW BY RICK VAN HORN, 8 UPDATE 68 CONCEPTS ADAM BUDOFSKY, AND RICK MATTINGLY Tommy Campbell, Footwork: 6 READERS' Joel Maitoza of 24-7 Spyz, A Balancing Act 45 Yamaha Snare Drums Gary Husband, and the BY ANDREW BY RICK MATTINGLY PLATFORM Moody Blues' Gordon KOLLMORGEN Marshall, plus News 47 Cappella 12 ASK A PRO 90 TEACHERS' Celebrity Sticks BY ADAM BUDOFSKY 146 INDUSTRY FORUM AND WILLIAM F. -

Booker Little

1 The TRUMPET of BOOKER LITTLE Solographer: Jan Evensmo Last update: Feb. 11, 2020 2 Born: Memphis, April 2, 1938 Died: NYC. Oct. 5, 1961 Introduction: You may not believe this, but the vintage Oslo Jazz Circle, firmly founded on the swinging thirties, was very interested in the modern trends represented by Eric Dolphy and through him, was introduced to the magnificent trumpet playing by the young Booker Little. Even those sceptical in the beginning gave in and agreed that here was something very special. History: Born into a musical family and played clarinet for a few months before taking up the trumpet at the age of 12; he took part in jam sessions with Phineas Newborn while still in his teens. Graduated from Manassas High School. While attending the Chicago Conservatory (1956-58) he played with Johnny Griffin and Walter Perkins’s group MJT+3; he then played with Max Roach (June 1958 to February 1959), worked as a freelancer in New York with, among others, Mal Waldron, and from February 1960 worked again with Roach. With Eric Dolphy he took part in the recording of John Coltrane’s album “Africa Brass” (1961) and led a quintet at the Five Spot in New York in July 1961. Booker Little’s playing was characterized by an open, gentle tone, a breathy attack on individual notes, a nd a subtle vibrato. His soli had the brisk tempi, wide range, and clean lines of hard bop, but he also enlarged his musical vocabulary by making sophisticated use of dissonance, which, especially in his collaborations with Dolphy, brought his playing close to free jazz. -

Victory and Sorrow: the Music & Life of Booker Little

ii VICTORY AND SORROW: THE MUSIC & LIFE OF BOOKER LITTLE by DYLAN LAGAMMA A Dissertation submitted to the Graduate School-Newark Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Graduate Program in Jazz History & Research written under the direction of Henry Martin and approved by _________________________ _________________________ Newark, New Jersey October 2017 i ©2017 Dylan LaGamma ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION VICTORY AND SORROW: THE MUSICAL LIFE OF BOOKER LITTLE BY DYLAN LAGAMMA Dissertation Director: Henry Martin Booker Little, a masterful trumpeter and composer, passed away in 1961 at the age of twenty-three. Little's untimely death, and still yet extensive recording career,1 presents yet another example of early passing among innovative and influential trumpeters. Like Clifford Brown before him, Theodore “Fats” Navarro before him, Little's death left a gap the in jazz world as both a sophisticated technician and an inspiring composer. However, unlike his predecessors Little is hardly – if ever – mentioned in jazz texts and classrooms. His influence is all but non-existent except to those who have researched his work. More than likely he is the victim of too early a death: Brown passed away at twenty-five and Navarro, twenty-six. Bob Cranshaw, who is present on Little's first recording,2 remarks, “Nobody got a chance to really experience [him]...very few remember him because nobody got a chance to really hear him or see him.”3 Given this, and his later work with more avant-garde and dissonant harmonic/melodic structure as a writing partner with Eric Dolphy, it is no wonder that his remembered career has followed more the path of James P. -

Johnny O'neal

OCTOBER 2017—ISSUE 186 YOUR FREE GUIDE TO THE NYC JAZZ SCENE NYCJAZZRECORD.COM BOBDOROUGH from bebop to schoolhouse VOCALS ISSUE JOHNNY JEN RUTH BETTY O’NEAL SHYU PRICE ROCHÉ Managing Editor: Laurence Donohue-Greene Editorial Director & Production Manager: Andrey Henkin To Contact: The New York City Jazz Record 66 Mt. Airy Road East OCTOBER 2017—ISSUE 186 Croton-on-Hudson, NY 10520 United States Phone/Fax: 212-568-9628 NEw York@Night 4 Laurence Donohue-Greene: Interview : JOHNNY O’NEAL 6 by alex henderson [email protected] Andrey Henkin: [email protected] Artist Feature : JEN SHYU 7 by suzanne lorge General Inquiries: [email protected] ON The Cover : BOB DOROUGH 8 by marilyn lester Advertising: [email protected] Encore : ruth price by andy vélez Calendar: 10 [email protected] VOXNews: Lest We Forget : betty rochÉ 10 by ori dagan [email protected] LAbel Spotlight : southport by alex henderson US Subscription rates: 12 issues, $40 11 Canada Subscription rates: 12 issues, $45 International Subscription rates: 12 issues, $50 For subscription assistance, send check, cash or VOXNEwS 11 by suzanne lorge money order to the address above or email [email protected] obituaries Staff Writers 12 David R. Adler, Clifford Allen, Duck Baker, Fred Bouchard, Festival Report Stuart Broomer, Robert Bush, 13 Thomas Conrad, Ken Dryden, Donald Elfman, Phil Freeman, Kurt Gottschalk, Tom Greenland, special feature 14 by andrey henkin Anders Griffen, Tyran Grillo, Alex Henderson, Robert Iannapollo, Matthew Kassel, Marilyn Lester, CD ReviewS 16 Suzanne Lorge, Mark Keresman, Marc Medwin, Russ Musto, John Pietaro, Joel Roberts, Miscellany 41 John Sharpe, Elliott Simon, Andrew Vélez, Scott Yanow Event Calendar Contributing Writers 42 Brian Charette, Ori Dagan, George Kanzler, Jim Motavalli “Think before you speak.” It’s something we teach to our children early on, a most basic lesson for living in a society. -

Leadership, Teamwork, Innovation and All That Jazz

ENABLING COLLECTIVE IMPROVISATION ADRIAN CHO in AGILE SOFTWARE DEVELOPMENT “Modern Business is Pure Chaos” Fast Company, January 2012 © Copyright Adrian Cho 2009-2012. All Rights Reserved. 2 THE AGILE RESPONSE Change Innovate Complexity Improvise Iterate Confusion © Copyright Adrian Cho 2009-2012. All Rights Reserved. 3 TAKING FALSE COMFORT IN RIGIDITY PREDICT Tools Technology Processes Practices © Copyright Adrian Cho 2009-2012. All Rights Reserved. 4 LEARNING FROM THE MILITARY “We know that the best equipment in the world without the right person operating it will not accomplish the mission. On the other hand, the right person will find a way to succeed with almost any equipment available.” Gen.Wayne A. Downing, Commander, U.S. Special Operations Command “People, ideas, hardware – in that order” Col. John Boyd, fighter pilot, instructor, strategist and aircraft designer The Special Operations Forces Truths 1. Humans are more important than Hardware. 2. Quality is better than Quantity. 3. Special Operations Forces cannot be mass produced. 4. Competent Special Operations Forces cannot be created after emergencies occur. Brig. Gen. David J. Baratto, Commander, JFK Special Warfare Center © Copyright Adrian Cho 2009-2012. All Rights Reserved. 5 LEARNING FROM MANUFACTURING “There is something called standard work, but standards should be changed constantly. Instead, if you think of the standard as the best you can do, it's all over. The standard work is only a baseline for doing further kaizen. It is kai-aku [change for the worse] if things get worse than now, and it is kaizen [change for the better] if things get better than now. Standards are set arbitrarily by humans, so how can they not change?” Taiichi Ohno, originator of the Toyota Production System Aim for continuous improvement Conduct regular retrospectives Beware of taking false comfort in best practices Best practices are the best...until something changes © Copyright Adrian Cho 2009-2012. -

Jazzpress 0615

CZERWIEC 2015 Gazeta internetowa poświęcona muzyce improwizowanej ISSN 2084-3143 ISSN TOP NOTE PeGaPoFo – Świeżość REAKTYWACJA! Bartłomiej Rozmowy: Oleś Piotr Schmidt Jestem uzależniony Asia Czajkowska-Zoń od brzmienia Charles Gayle Majerczyk Kuba fot. Oleś, Bartłomiej dziękujemy! < Od Redakcji Udało się! Reaktywacja RadioJAZZ.FM stała się faktem – a wszystko dzięki Wam! Zorga- nizowana na portalu Wspieram.to zbiórka społecznościowa zakończyła się sukcesem. Zebraliśmy ponad dwa razy więcej pieniędzy, niż przewidywaliśmy, co umożliwi nam lepszy start oraz zapewni stabilne działanie! Jesteśmy teraz w stu procentach pewni, że już niedługo będziemy mogli ruszyć z nadawaniem muzyki – planujemy start na wrze- sień bieżącego roku. Teraz przed nami sporo pracy, aby przygotować sprzęt do naszych jazzowych potrzeb, stworzyć elegancką i przejrzystą stronę internetową oraz aplikację, dzięki której każdy będzie mógł słuchać prezentowanej przez nas muzyki przez komór- kę – na spacerze, na wyjeździe, w komunikacji miejskiej czy w samochodzie. Dziękujemy Wam, drodzy słuchacze RadioJAZZ.FM i czytelnicy JazzPRESSu. To dzię- ki Waszemu zaangażowaniu i Waszym wpłatom nasza akcja się powiodła, a my bę- dziemy mogli z pełną mocą ruszyć i dumnie działać jako jedyne w Polsce radio jazzo- we! Dziękujemy także wszystkim tym, którzy tak pięknie bawili się hasłem #jazzdoit i przysyłali do nas pomysłowe zdjęcia. Z tego miejsca chcemy podziękować także wszystkim naszym ambasadorom oraz przyjaciołom, którzy mają jazz w sercu i pomogli nam rozpowszechnić informację -

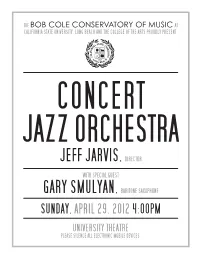

Jeff Jarvis,Director

CONCERT JAZZ ORCHESTRA JEFF JARVIS, DIRECTOR WITH SPECIAL GUEST GARY SMULYAN, BARITONE SAXOPHONE SUNDAY, APRIL 29, 2012 4:00PM UNIVERSITY THEATRE PLEASE SILENCE ALL ELECTRONIC MOBILE DEVICES. TONIGHT’S PROGRAM GENTLY / Bob Mintzer This well-crafted original is the title track of a recording of the Bob Mintzer Big Band. This recording project was unique in that the horn section stood in a circle surrounding a specially designed ribbon microphone that was extremely sensitive and accurate. This microphone would not accept loud dynamic levels, so Bob Mintzer wrote material that showcased the band playing at softer dynamics, which resulted in frequent use of muted brass, flugelhorns, and woodwinds. Today’s soloists include Josh Andree (tenor sax) and Will Brahm (guitar). THEN AND NOW / George Stone This terrific original composition and arrangement is featured on a recent recording of the George Stone Big Band entitled “The Real Deal”, performed by a collection of Southern California’s finest studio musicians. George’s music is frequently featured at our concerts because of its superior quality, both from a compositional standpoint and also in terms of orchestration. This piece has it all—melodic integrity, intense rhythms, lush harmonies, and sufficient solo space. Today’s soloists include Eun young Koh (piano), Josh Andree (tenor sax), Will Brahm (guitar), and Daniel Hutton (alto sax). CHINA BLUE / Jeff Jarvis Originally composed as a commission for a big band in Williamsburg VA, the work features a winding trumpet melody supported by muted trombone parts, warm flugelhorn lines, and beautiful woodwind parts played by the saxophone section. The piece proves challenging since the musicians are faced with executing exposed parts with delicacy and restraint. -

The Evolution of Ornette Coleman's Music And

DANCING IN HIS HEAD: THE EVOLUTION OF ORNETTE COLEMAN’S MUSIC AND COMPOSITIONAL PHILOSOPHY by Nathan A. Frink B.A. Nazareth College of Rochester, 2009 M.A. University of Pittsburgh, 2012 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The Kenneth P. Dietrich School of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2016 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH THE KENNETH P. DIETRICH SCHOOL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES This dissertation was presented by Nathan A. Frink It was defended on November 16, 2015 and approved by Lawrence Glasco, PhD, Professor, History Adriana Helbig, PhD, Associate Professor, Music Matthew Rosenblum, PhD, Professor, Music Dissertation Advisor: Eric Moe, PhD, Professor, Music ii DANCING IN HIS HEAD: THE EVOLUTION OF ORNETTE COLEMAN’S MUSIC AND COMPOSITIONAL PHILOSOPHY Nathan A. Frink, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2016 Copyright © by Nathan A. Frink 2016 iii DANCING IN HIS HEAD: THE EVOLUTION OF ORNETTE COLEMAN’S MUSIC AND COMPOSITIONAL PHILOSOPHY Nathan A. Frink, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2016 Ornette Coleman (1930-2015) is frequently referred to as not only a great visionary in jazz music but as also the father of the jazz avant-garde movement. As such, his work has been a topic of discussion for nearly five decades among jazz theorists, musicians, scholars and aficionados. While this music was once controversial and divisive, it eventually found a wealth of supporters within the artistic community and has been incorporated into the jazz narrative and canon. Coleman’s musical practices found their greatest acceptance among the following generations of improvisers who embraced the message of “free jazz” as a natural evolution in style. -

Stylistic Evolution of Jazz Drummer Ed Blackwell: the Cultural Intersection of New Orleans and West Africa

STYLISTIC EVOLUTION OF JAZZ DRUMMER ED BLACKWELL: THE CULTURAL INTERSECTION OF NEW ORLEANS AND WEST AFRICA David J. Schmalenberger Research Project submitted to the College of Creative Arts at West Virginia University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in Percussion/World Music Philip Faini, Chair Russell Dean, Ph.D. David Taddie, Ph.D. Christopher Wilkinson, Ph.D. Paschal Younge, Ed.D. Division of Music Morgantown, West Virginia 2000 Keywords: Jazz, Drumset, Blackwell, New Orleans Copyright 2000 David J. Schmalenberger ABSTRACT Stylistic Evolution of Jazz Drummer Ed Blackwell: The Cultural Intersection of New Orleans and West Africa David J. Schmalenberger The two primary functions of a jazz drummer are to maintain a consistent pulse and to support the soloists within the musical group. Throughout the twentieth century, jazz drummers have found creative ways to fulfill or challenge these roles. In the case of Bebop, for example, pioneers Kenny Clarke and Max Roach forged a new drumming style in the 1940’s that was markedly more independent technically, as well as more lyrical in both time-keeping and soloing. The stylistic innovations of Clarke and Roach also helped foster a new attitude: the acceptance of drummers as thoughtful, sensitive musical artists. These developments paved the way for the next generation of jazz drummers, one that would further challenge conventional musical roles in the post-Hard Bop era. One of Max Roach’s most faithful disciples was the New Orleans-born drummer Edward Joseph “Boogie” Blackwell (1929-1992). Ed Blackwell’s playing style at the beginning of his career in the late 1940’s was predominantly influenced by Bebop and the drumming vocabulary of Max Roach.