Linguistics 101 Mophology

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Moroccan Arabic Borrowed Circumfix from Berber: Investigating Morphological Categories in a Language Contact Situation

Lingvistika-2011-01-93 1/5/12 1:32 PM Page 231 Georgia Zellou UDK 811.411.21(64)’06:811.413 University of Colorado Boulder* MOROCCAN ARABIC BORROWED CIRCUMFIX FROM BERBER: INVESTIGATING MORPHOLOGICAL CATEGORIES IN A LANGUAGE CONTACT SITUATION 1. INTRODUCTION Moroccan Arabic (MA, hereafter) has a bound derivational noun circumfix /ta-. .-t/. This circumfix productively attaches to base nouns to derive various types of abstract nouns. This /ta-. .-t/ circumfix is unique because it occurs in no other dialect of Arabic (Abdel-Massih 2009, Bergman 2005, Erwin 1963). There is little question that this mor - pheme has been borrowed from Berber into Moroccan Arabic, as has been noted by some of the earliest analyses of the language (c.f. Guay 1918, Colon 1945). This circumfix is highly productive on native MA noun stems but not productive on borrowed Berber stems (which are rare in MA). This pattern of productivity is taken to be evidence in support of direct borrowing of morphology (c.f. Steinkruger and Seifart 2009) and against a theory where borrowed morphology enters a language as part of unanalyzed complex forms which later spread to native stems (c.f. Thomason and Kaufman 1988; Thomason 2001). Furthermore, it challenges the principle of a “borrowability hierarchy” (c.f. Haugen 1950) where lexical morphemes are borrowed before grammatical morphemes. Additionally, the prefixal portion of the MA circumfix, ta- , is a complex (presumably unanalyzed) form from the Berber /t-/ feminine + /a-/ absolute state. Moreover, the morpheme in MA has been bor - rowed as a derivational morpheme while the primary functions of the donor mor - phemes in Berber are inflectional. -

Creating Words: Is Lexicography for You? Lexicographers Decide Which Words Should Be Included in Dictionaries. They May Decide T

Creating Words: Is Lexicography for You? Lexicographers decide which words should be included in dictionaries. They may decide that a word is currently just a fad, and so they’ll wait to see whether it will become a permanent addition to the language. In the past several decades, words such as hippie and yuppie have survived being fads and are now found in regular, not just slang, dictionaries. Other words, such as medicare, were created to fill needs. And yet other words have come from trademark names, for example, escalator. Here are some writing options: 1. While you probably had to memorize vocabulary words throughout your school years, you undoubtedly also learned many other words and ways of speaking and writing without even noticing it. What factors are bringing about changes in the language you now speak and write? Classes? Songs? Friends? Have you ever influenced the language that someone else speaks? 2. How often do you use a dictionary or thesaurus? What helps you learn a new word and remember its meaning? 3. Practice being a lexicographer: Define a word that you know isn’t in the dictionary, or create a word or set of words that you think is needed. When is it appropriate to use this term? Please give some sample dialogue or describe a specific situation in which you would use the term. For inspiration, you can read the short article in the Writing Center by James Chiles about the term he has created "messismo"–a word for "true bachelor housekeeping." 4. Or take a general word such as "good" or "friend" and identify what it means in different contexts or the different categories contained within the word. -

Traditional Grammar

Traditional Grammar Traditional grammar refers to the type of grammar study Continuing with this tradition, grammarians in done prior to the beginnings of modern linguistics. the eighteenth century studied English, along with many Grammar, in this traditional sense, is the study of the other European languages, by using the prescriptive structure and formation of words and sentences, usually approach in traditional grammar; during this time alone, without much reference to sound and meaning. In the over 270 grammars of English were published. During more modern linguistic sense, grammar is the study of the most of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, grammar entire interrelated system of structures— sounds, words, was viewed as the art or science of correct language in meanings, sentences—within a language. both speech and writing. By pointing out common Traditional grammar can be traced back over mistakes in usage, these early grammarians created 2,000 years and includes grammars from the classical grammars and dictionaries to help settle usage arguments period of Greece, India, and Rome; the Middle Ages; the and to encourage the improvement of English. Renaissance; the eighteenth and nineteenth century; and One of the most influential grammars of the more modern times. The grammars created in this eighteenth century was Lindley Murray’s English tradition reflect the prescriptive view that one dialect or grammar (1794), which was updated in new editions for variety of a language is to be valued more highly than decades. Murray’s rules were taught for many years others and should be the norm for all speakers of the throughout school systems in England and the United language. -

Syntax and Morphology Semantics

Parent Tip Sheet Language Syntax & Morphology yntax is the development of sentence structure meaning your child’s first attempts at putting two words together. SMorphology refers to the structure and construction of words and the rules that determine changes in word meaning; it’s knowing plural forms 9 and correct use of verb tense. Introduce words from many different categories: nouns, verbs, adjectives, adverbs, prepositions and conjunctions. The emergence of first words 9 typically begins around 12 months of Use the Plus One Rule: add a word to expand the length of your child’s utterance to model longer sentences. Also use correct grammar, even age. Syntax typically begins when if it means adding more than one word. E.g., if your child says ‘blue a child begins to combine words in ball” you can say “The blue ball is big.” early two word utterances (ex. Daddy 9 work) around 18-24 months. Read books with repetition, such as: We’re Going on a Bear Hunt or I Went Walking. 9 A child needs approximately 50 Watch videos of people or objects in action and describe what is happening. words to begin to combine them 9 Pay attention to the use of plurals with an “s”, add them whenever into short phrases. When children possible. Point out words that do not use an “s” to be plural (e.g., men, begin to learn words, they learn that children) to understand placement in space. some words refer to objects, some 9 Play games with “in” and “on.” To focus on correlation with space. -

The Generative Lexicon

The Generative Lexicon James Pustejovsky" Computer Science Department Brandeis University In this paper, I will discuss four major topics relating to current research in lexical seman- tics: methodology, descriptive coverage, adequacy of the representation, and the computational usefulness of representations. In addressing these issues, I will discuss what I think are some of the central problems facing the lexical semantics community, and suggest ways of best ap- proaching these issues. Then, I will provide a method for the decomposition of lexical categories and outline a theory of lexical semantics embodying a notion of cocompositionality and type coercion, as well as several levels of semantic description, where the semantic load is spread more evenly throughout the lexicon. I argue that lexical decomposition is possible if it is per- formed generatively. Rather than assuming a fixed set of primitives, I will assume a fixed number of generative devices that can be seen as constructing semantic expressions. I develop a theory of Qualia Structure, a representation language for lexical items, which renders much lexical ambiguity in the lexicon unnecessary, while still explaining the systematic polysemy that words carry. Finally, I discuss how individual lexical structures can be integrated into the larger lexical knowledge base through a theory of lexical inheritance. This provides us with the necessary principles of global organization for the lexicon, enabling us to fully integrate our natural language lexicon into a conceptual whole. 1. Introduction I believe we have reached an interesting turning point in research, where linguistic studies can be informed by computational tools for lexicology as well as an appre- ciation of the computational complexity of large lexical databases. -

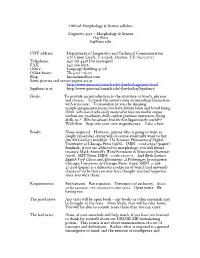

Official! Morphology & Syntax Syllabus

Official Morphology & Syntax syllabus Linguistics 4050 – Morphology & Syntax Haj Ross [email protected] UNT address: Department of Linguistics and Technical Communication 1155 Union Circle, # 305298, Denton, TX 76203-5017 Telephone: 940 565 4458 [for messages] FAX: 940 369 8976 Office: Language Building 407K Office hours: Th 4:00 – 6:00 Blog: haj.nadamelhor.com Some poetics and syntax papers are at http://www-personal.umich.edu/~jlawler/hajpapers.html Squibnet is at http://www-personal.umich.edu/~jlawler/haj/Squibnet/ Goals: To provide an introduction to the structure of words, phrases and clauses. To hook the unwary into an unending fascination with structure. To reawaken in you the sleeping morphopragmantactician you have always been and loved being. (Hint: who was it who easily mastered at least one mother tongue without any vocabulary drills, explicit grammar instruction, boring drills, etc.? Who has always been the best linguist in the world??) Well then. Step into your own magnificence. Take a bow. Books: None required. However, anyone who is going to want to deeply remember syntax will of course eventually want to buy Jim McCawley’s indelible The Syntactic Phenomena of English University of Chicago Press (1988). ISBN: 0226556247 (paper). Similarly, if you are addicted to morphology, you will always treasure Mark Aronoff’s Word Formation in Generative Grammar (1976). MIT Press. ISBN: 0-262-51017-0. And Beth Levin’s English Verb Classes and Alternations: A Preliminary Investigation. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. (1993) ISBN 0-226- 47533-6 (paper) is a delicious cookie jar of weird (and unweird) classes of verbs that you may have thought you had forgotten since you were three. -

Character-Word LSTM Language Models

Character-Word LSTM Language Models Lyan Verwimp Joris Pelemans Hugo Van hamme Patrick Wambacq ESAT – PSI, KU Leuven Kasteelpark Arenberg 10, 3001 Heverlee, Belgium [email protected] Abstract A first drawback is the fact that the parameters for infrequent words are typically less accurate because We present a Character-Word Long Short- the network requires a lot of training examples to Term Memory Language Model which optimize the parameters. The second and most both reduces the perplexity with respect important drawback addressed is the fact that the to a baseline word-level language model model does not make use of the internal structure and reduces the number of parameters of the words, given that they are encoded as one-hot of the model. Character information can vectors. For example, ‘felicity’ (great happiness) is reveal structural (dis)similarities between a relatively infrequent word (its frequency is much words and can even be used when a word lower compared to the frequency of ‘happiness’ is out-of-vocabulary, thus improving the according to Google Ngram Viewer (Michel et al., modeling of infrequent and unknown words. 2011)) and will probably be an out-of-vocabulary By concatenating word and character (OOV) word in many applications, but since there embeddings, we achieve up to 2.77% are many nouns also ending on ‘ity’ (ability, com- relative improvement on English compared plexity, creativity . ), knowledge of the surface to a baseline model with a similar amount of form of the word will help in determining that ‘felic- parameters and 4.57% on Dutch. Moreover, ity’ is a noun. -

Greek and Latin Roots, Prefixes, and Suffixes

GREEK AND LATIN ROOTS, PREFIXES, AND SUFFIXES This is a resource pack that I put together for myself to teach roots, prefixes, and suffixes as part of a separate vocabulary class (short weekly sessions). It is a combination of helpful resources that I have found on the web as well as some tips of my own (such as the simple lesson plan). Lesson Plan Ideas ........................................................................................................... 3 Simple Lesson Plan for Word Study: ........................................................................... 3 Lesson Plan Idea 2 ...................................................................................................... 3 Background Information .................................................................................................. 5 Why Study Word Roots, Prefixes, and Suffixes? ......................................................... 6 Latin and Greek Word Elements .............................................................................. 6 Latin Roots, Prefixes, and Suffixes .......................................................................... 6 Root, Prefix, and Suffix Lists ........................................................................................... 8 List 1: MEGA root list ................................................................................................... 9 List 2: Roots, Prefixes, and Suffixes .......................................................................... 32 List 3: Prefix List ...................................................................................................... -

Basic Morphology

What is Morphology? Mark Aronoff and Kirsten Fudeman MORPHOLOGY AND MORPHOLOGICAL ANALYSIS 1 1 Thinking about Morphology and Morphological Analysis 1.1 What is Morphology? 1 1.2 Morphemes 2 1.3 Morphology in Action 4 1.3.1 Novel words and word play 4 1.3.2 Abstract morphological facts 6 1.4 Background and Beliefs 9 1.5 Introduction to Morphological Analysis 12 1.5.1 Two basic approaches: analysis and synthesis 12 1.5.2 Analytic principles 14 1.5.3 Sample problems with solutions 17 1.6 Summary 21 Introduction to Kujamaat Jóola 22 mor·phol·o·gy: a study of the structure or form of something Merriam-Webster Unabridged n 1.1 What is Morphology? The term morphology is generally attributed to the German poet, novelist, playwright, and philosopher Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (1749–1832), who coined it early in the nineteenth century in a biological context. Its etymology is Greek: morph- means ‘shape, form’, and morphology is the study of form or forms. In biology morphology refers to the study of the form and structure of organisms, and in geology it refers to the study of the configuration and evolution of land forms. In linguistics morphology refers to the mental system involved in word formation or to the branch 2 MORPHOLOGYMORPHOLOGY ANDAND MORPHOLOGICAL MORPHOLOGICAL ANALYSIS ANALYSIS of linguistics that deals with words, their internal structure, and how they are formed. n 1.2 Morphemes A major way in which morphologists investigate words, their internal structure, and how they are formed is through the identification and study of morphemes, often defined as the smallest linguistic pieces with a gram- matical function. -

Types and Functions of Reduplication in Palembang

Journal of the Southeast Asian Linguistics Society JSEALS 12.1 (2019): 113-142 ISSN: 1836-6821, DOI: http://hdl.handle.net/10524/52447 University of Hawaiʼi Press TYPES AND FUNCTIONS OF REDUPLICATION IN PALEMBANG Mardheya Alsamadani & Samar Taibah Wayne State University [email protected] & [email protected] Abstract In this paper, we study the morphosemantic aspects of reduplication in Palembang (also known as Musi). In Palembang, both content and function words undergo reduplication, generating a wide variety of semantic functions, such as pluralization, iteration, distribution, and nominalization. Productive reduplication includes full reduplication and reduplication plus affixation, while fossilized reduplication includes partial reduplication and rhyming reduplication. We employed the Distributed Morphology theory (DM) (Halle and Marantz 1993, 1994) to account for these different patterns of reduplication. Moreover, we compared the functions of Palembang reduplication to those of Malay and Indonesian reduplication. Some instances of function word reduplication in Palembang were not found in these languages, such as reduplication of question words and reduplication of negators. In addition, Palembang partial reduplication is fossilized, with only a few examples collected. In contrast, Malay partial reduplication is productive and utilized to create new words, especially words borrowed from English (Ahmad 2005). Keywords: Reduplication, affixation, Palembang/Musi, morphosemantics ISO 639-3 codes: mui 1 Introduction This paper has three purposes. The first is to document the reduplication patterns found in Palembang based on the data collected from three Palembang native speakers. Second, we aim to illustrate some shared features of Palembang reduplication with those found in other Malayic languages such as Indonesian and Malay. The third purpose is to provide a formal analysis of Palembang reduplication based on the Distributed Morphology Theory. -

Morphophonology of Magahi

International Journal of Science and Research (IJSR) ISSN: 2319-7064 SJIF (2019): 7.583 Morphophonology of Magahi Saloni Priya Jawaharlal Nehru University, SLL & CS, New Delhi, India Salonipriya17[at]gmail.com Abstract: Every languages has different types of word formation processes and each and every segment of morphology has a sound. The following paper is concerned with the sound changes or phonemic changes that occur during the word formation process in Magahi. Magahi is an Indo- Aryan Language spoken in eastern parts of Bihar and also in some parts of Jharkhand and West Bengal. The term Morphophonology refers to the interaction of word formation with the sound systems of a language. The paper finds out the phonetic rules interacting with the morphology of lexicons of Magahi. The observations shows that he most frequent morphophonological process are Sandhi, assimilation, Metathesis and Epenthesis. Whereas, the process of Dissimilation, Lenition and Fortition are very Uncommon in nature. Keywords: Morphology, Phonology, Sound Changes, Word formation process, Magahi, Words, Vowels, Consonants 1. Introduction 3.1 The Sources of Magahi Glossary Morphophonology refers to the interaction between Magahi has three kind of vocabulary sources; morphological and phonological or its phonetic processes. i) In the first category, it has those lexemes which has The aim of this paper is to give a detailed account on the been processed or influenced by Sanskrit, Prakrit, sound changes that take place in morphemes, when they Apbhransh, ect. Like, combine to form new words in the language. धमम> ध륍म> धरम, स셍म> सꥍ셍> सााँ셍 ii) In the second category, it has those words which are 2. -

12 Morphology and Lexical Semantics

248 Beth Levin and Malka Rappaport Hovav 12 Morphology and Lexical Semantics BETH LEVIN AND MALKA RAPPAPORT HOVAV The relation between lexical semantics and morphology has not been the subject of much study. This may seem surprising, since a morpheme is often viewed as a minimal Saussurean sign relating form and meaning: it is a concept with a phonologically composed name. On this view, morphology has both a semantic side and a structural side, the latter sometimes called “morphological realization” (Aronoff 1994, Zwicky 1986b). Since morphology is the study of the structure and derivation of complex signs, attention could be focused on the semantic side (the composition of complex concepts) and the structural side (the composition of the complex names for the concepts) and the relation between them. In fact, recent work in morphology has been concerned almost exclusively with the composition of complex names for concepts – that is, with the struc- tural side of morphology. This dissociation of “form” from “meaning” was foreshadowed by Aronoff’s (1976) demonstration that morphemes are not necessarily associated with a constant meaning – or any meaning at all – and that their nature is basically structural. Although in early generative treat- ments of word formation, semantic operations accompanied formal morpho- logical operations (as in Aronoff’s Word Formation Rules), many subsequent generative theories of morphology, following Lieber (1980), explicitly dissoci- ate the lexical semantic operations of composition from the formal structural