Saussure's Value(S)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Inside Africa

INSIDE AFRICA 17 February 2017 Now is the time to invest in Africa BRIEFS Africa • G20 foreign ministers to tackle fight against poverty in Africa • West African CFA franc zone to see strong growth, increased CONTENTS risks: IMF • Ecobank CEO wants 100 mln customers by 2020 In-Depth: Angola - Africa can become a global economic powerhouse. This is • Angola's economy contracted 4.3 percent in Q3, 2016 - stats how .......................................................................................... 2 agency • - Making Renewable Energy More Accessible in Sub-Saharan Angola inflation slows to 40.4 percent year/year in January • Non-resident investors will be able to invest in Angola Stock Africa ................................................................................. 3 Exchange • IMF, WORLD BANK& AFDB ................................................... 5 Eni starts production of East Pole field in Angola - state oil firm • INVESTMENTS ........................................................................... 8 Angola’s Endiama negotiates financing for another diamond project BANKING Egypt • Banks ....................................................................................................... 10 Italy's Eni to start production in Egypt by end of year Ivory Coast Markets 11 .................................................................................................... • Ivory Coast consumer inflation rises to 1.1 pct yr/yr in January ENERGY .................................................................................... -

GIPE-011123-Contents.Pdf (1.391Mb)

THE PROBLEM OF INTERNATIONAL INVESTMENT The .Riiyal I ...tiIIute oj Intemalional Affairs i8 _ ..""jftcial tJnrl """.po!ilicaZ body,Joon.dtd ... 1920 to .....",..,.ag. tJnrl Jat>iZital. Ike 8cientific 8ttu% oj intemalionaZ qu<8t1of18. The 11l81i1ut., ... BUCh, i8 precluded by;u rvlu from upruring an opinion 011 any CUlpect oJ...,.,.• ....eionaZ "ffaVr8; opinionB upru.ed ... 1MB book or.. /hereJor., pur'11I indWiduoZ. THE PROBLEM OF INTERNATIONAL • INVESTMENT . A Report by a Study Group of Members of the Royal Institute of International Mairs OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS LONDON NEW YORK TORONTO 1 __ -urIM .....,.;_ ~IM R'¥IlI"- ~I-.. ..... -'~ 1937 ODORD UNIVERSITY PRBSS AMBN ROUBH, B.C. 4 London Bdlnbmgb Glalgow New York 'l'OlOIlto Melbourne Capetown Bomb., Calcutta Madru HUIIPHREY IIILII'ORD PVBLIBBBB W nm VIn'D8lfl' XbSZ;-. \.N3t &7 /1 ( 2.. J FOREWORD TIm Council of the Royal Institute of International Affairs believe that this a.ddition to the series of Study Group Reports will fill an important gap in the literature of international economics. It is an attempt, in the first ple.ce, to e.na.lyse objectively the conditions under which long-term oapital may move between countries and to consider oe.refully the speoie.l fe.otors in the world economy of to-day which tend to limit the extent to which such movements e.re possible or desirable. Secondly, the book contains a careful study of the post war history of international investments which brings together facts and figures whioh e.re ine.ocessible to most students and business men. The Council is indebted to the following group of members of the Institute for the preparation of the Report: Mr. -

The World Bank

Document of The World Bank FOR OFFICIAL USE ONLY Ca- ZC~ / 3 7 Public Disclosure Authorized Report No. 7630-BO STAFF APPRAISALREPORT Public Disclosure Authorized REPUBLICOF BOLIVIA MINING SECTORREHABILITATION PROJECT APRIL 17, 1989 Public Disclosure Authorized Industry,Trade and FinanceOperations Division Country DepartmentIII Public Disclosure Authorized Latin America and the CaribbeanRegion This document hasa resticted dsibuto0vand may be used by oenpienlsoly In the perdonnanoe of their official duties. Its contents may - A otherwise be disclosed wt World Bank authorizatin CURRENCYEQUIVALENTS Currency Name - Boliviano US$1.00 - Bolivianos 2.47 Bolivianos 1.00 - US$0.405 FISCAL YEAR January 1 to December 31 WEIGHTS AND MEASURES 1 meter (m) G 3.281 feet (ft) 1 kilometer (km) = 0.622 miles (mi) 1 kilogram (kg) 2.205 pounds (lb) 1 troy ounce (troy oz) - 31.: grams 1 gram (g) - .032 troy ox 1 metric tonne (mt) - S2,151 troy oz | 2.205 lbs 1 short ton (T) - 2,000 lbs PRINCIPAL ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS BAMIN - Banco Minero BCB - Banco Central de Bolivia SA - Banco Industrial SA . - Centro de Investigacion Minero Metalurgica IMITBOL - Corporacion Hinera de Bolivia -'D - Development Credit Department (Central Bank) ,TAW - Empresa Nacional de Fundiciones FCNEM - Fondo Nacional de Exploracion Minera FSE - Fondo Social de Emergencia FSTMN - Federacion Sindical de Trabajadores Mineros de Bolivia GEOBOL - Servicio Geologico de Bolivia IDB - Interamerican Developi*ent Bank IDM - Instituto de Desarrollo Minero INK - Instituto de Investigacion Minero Metalurgica MMK - Ministry of Mining and Metallurgy STCM - Servicio Tecnico del Cadastro Minero FOR OMFCIL USE ONLY STAFF APPRAISAL REPORT BOLIVIA MINING SECTOR REHABILITATION PROJECT TABLE OF CONTENTS Page No. -

Marketing Semiotics

Marketing Semiotics Professor Christian Pinson Semiosis, i.e. the process by which things and events come to be recognized as signs, is of particular relevance to marketing scholars and practitioners. The term marketing encompasses those activities involved in identifying the needs and wants of target markets and delivering the desired satisfactions more effectively and efficiently than competitors. Whereas early definitions of marketing focused on the performance of business activities that direct the flow of goods and services from producer to consumer or user, modern definitions stress that marketing activities involve interaction between seller and buyer and not a one- way flow from producer to consumer. As a consequence, the majority of marketers now view marketing in terms of exchange relationships. These relationships entail physical, financial, psychological and social meanings. The broad objective of the semiotics of marketing is to make explicit the conditions under which these meanings are produced and apprehended. Although semioticians have been actively working in the field of marketing since the 1960s, it is only recently that semiotic concepts and approaches have received international attention and recognition (for an overview, see Larsen et al. 1991, Mick, 1986, 1997 Umiker- Sebeok, 1988, Pinson, 1988). Diffusion of semiotic research in marketing has been made difficult by cultural and linguistic barriers as well as by divergence of thought. Whereas Anglo-Saxon researchers base their conceptual framework on Charles Pierce's ideas, Continental scholars tend to refer to the sign theory in Ferdinand de Saussure and to its interpretation by Hjelmslev. 1. The symbolic nature of consumption. Consumer researchers and critics of marketing have long recognized the symbolic nature of consumption and the importance of studying the meanings attached by consumers to the various linguistic and non-linguistic signs available to them in the marketplace. -

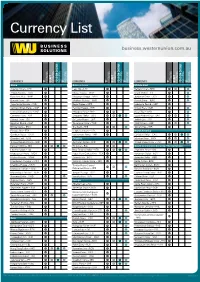

View Currency List

Currency List business.westernunion.com.au CURRENCY TT OUTGOING DRAFT OUTGOING FOREIGN CHEQUE INCOMING TT INCOMING CURRENCY TT OUTGOING DRAFT OUTGOING FOREIGN CHEQUE INCOMING TT INCOMING CURRENCY TT OUTGOING DRAFT OUTGOING FOREIGN CHEQUE INCOMING TT INCOMING Africa Asia continued Middle East Algerian Dinar – DZD Laos Kip – LAK Bahrain Dinar – BHD Angola Kwanza – AOA Macau Pataca – MOP Israeli Shekel – ILS Botswana Pula – BWP Malaysian Ringgit – MYR Jordanian Dinar – JOD Burundi Franc – BIF Maldives Rufiyaa – MVR Kuwaiti Dinar – KWD Cape Verde Escudo – CVE Nepal Rupee – NPR Lebanese Pound – LBP Central African States – XOF Pakistan Rupee – PKR Omani Rial – OMR Central African States – XAF Philippine Peso – PHP Qatari Rial – QAR Comoros Franc – KMF Singapore Dollar – SGD Saudi Arabian Riyal – SAR Djibouti Franc – DJF Sri Lanka Rupee – LKR Turkish Lira – TRY Egyptian Pound – EGP Taiwanese Dollar – TWD UAE Dirham – AED Eritrea Nakfa – ERN Thai Baht – THB Yemeni Rial – YER Ethiopia Birr – ETB Uzbekistan Sum – UZS North America Gambian Dalasi – GMD Vietnamese Dong – VND Canadian Dollar – CAD Ghanian Cedi – GHS Oceania Mexican Peso – MXN Guinea Republic Franc – GNF Australian Dollar – AUD United States Dollar – USD Kenyan Shilling – KES Fiji Dollar – FJD South and Central America, The Caribbean Lesotho Malati – LSL New Zealand Dollar – NZD Argentine Peso – ARS Madagascar Ariary – MGA Papua New Guinea Kina – PGK Bahamian Dollar – BSD Malawi Kwacha – MWK Samoan Tala – WST Barbados Dollar – BBD Mauritanian Ouguiya – MRO Solomon Islands Dollar – -

Qualia NICHOLAS HARKNESS Harvard University, USA

Qualia NICHOLAS HARKNESS Harvard University, USA Qualia (singular, quale) are cultural emergents that manifest phenomenally as sensuous features or qualities. The anthropological challenge presented by qualia is to theorize elements of experience that are semiotically generated but apperceived as non-signs. Qualia are not reducible to a psychology of individual perceptions of sensory data, to a cultural ontology of “materiality,” or to philosophical intuitions about the subjective properties of consciousness. The analytical solution to the challenge of qualia is to con- sider tone in relation to the familiar linguistic anthropological categories of token and type. This solution has been made methodologically practical by conceptualizing qualia, in Peircean terms, as “facts of firstness” or firstness “under its form of secondness.” Inthephilosophyofmind,theterm“qualia”hasbeenusedtodescribetheineffable, intrinsic, private, and directly or immediately apprehensible experiences of “the way things seem,” which have been taken to constitute the atomic subjective properties of consciousness. This concept was challenged in an influential paper by Daniel Dennett, who argued that qualia “is a philosophers’ term which fosters nothing but confusion, and refers in the end to no properties or features at all” (Dennett 1988, 387). Dennett concluded, correctly, that these diverse elements of feeling, made sensuously present atvariouslevelsofattention,wereactuallyidiosyncraticresponsestoapperceptions of “public, relational” qualities. Qualia were, in effect, -

Sponsored by the Department of Science and Technology Volume

Volume 26 Number 3 • August 2015 Sponsored by the Department of Science and Technology Volume 26 Number 3 • August 2015 CONTENTS 2 Reliability benefit of smart grid technologies: A case for South Africa Angela Masembe 10 Low-income resident’s preferences for the location of wind turbine farms in the Eastern Cape Province, South Africa Jessica Hosking, Mario du Preez and Gary Sharp 19 Identification and characterisation of performance limiting defects and cell mismatch in photovoltaic modules Jacqui L Crozier, Ernest E van Dyk and Frederick J Vorster 27 A perspective on South African coal fired power station emissions Ilze Pretorius, Stuart Piketh, Roelof Burger and Hein Neomagus 41 Modelling energy supply options for electricity generations in Tanzania Baraka Kichonge, Geoffrey R John and Iddi S N Mkilaha 58 Options for the supply of electricity to rural homes in South Africa Noor Jamal 66 Determinants of energy poverty in South Africa Zaakirah Ismail and Patrick Khembo 79 An overview of refrigeration and its impact on the development in the Democratic Republic of Congo Jean Fulbert Ituna-Yudonago, J M Belman-Flores and V Pérez-García 90 Comparative bioelectricity generation from waste citrus fruit using a galvanic cell, fuel cell and microbial fuel cell Abdul Majeed Khan and Muhammad Obaid 100 The effect of an angle on the impact and flow quantity on output power of an impulse water wheel model Ram K Tyagi CONFERENCE PAPERS 105 Harnessing Nigeria’s abundant solar energy potential using the DESERTEC model Udochukwu B Akuru, Ogbonnaya -

Financial Panics and Scandals

Wintonbury Risk Management Investment Strategy Discussions www.wintonbury.com Financial Panics, Scandals and Failures And Major Events 1. 1343: the Peruzzi Bank of Florence fails after Edward III of England defaults. 2. 1621-1622: Ferdinand II of the Holy Roman Empire debases coinage during the Thirty Years War 3. 1634-1637: Tulip bulb bubble and crash in Holland 4. 1711-1720: South Sea Bubble 5. 1716-1720: Mississippi Bubble, John Law 6. 1754-1763: French & Indian War (European Seven Years War) 7. 1763: North Europe Panic after the Seven Years War 8. 1764: British Currency Act of 1764 9. 1765-1769: Post war depression, with farm and business foreclosures in the colonies 10. 1775-1783: Revolutionary War 11. 1785-1787: Post Revolutionary War Depression, Shays Rebellion over farm foreclosures. 12. Bank of the United States, 1791-1811, Alexander Hamilton 13. 1792: William Duer Panic in New York 14. 1794: Whiskey Rebellion in Western Pennsylvania (Gallatin mediates) 15. British currency crisis of 1797, suspension of gold payments 16. 1808: Napoleon Overthrows Spanish Monarchy; Shipping Marques 17. 1813: Danish State Default 18. 1813: Suffolk Banking System established in Boston and eventually all of New England to clear bank notes for members at par. 19. Second Bank of the United States, 1816-1836, Nicholas Biddle 20. Panic of 1819, Agricultural Prices, Bank Currency, and Western Lands 21. 1821: British restoration of gold payments 22. Republic of Poyais fraud, London & Paris, 1820-1826, Gregor MacGregor. 23. British Banking Crisis, 1825-1826, failed Latin American investments, etc., six London banks including Henry Thornton’s Bank and sixty country banks failed. -

The Unicode Standard, Version 6.3

Currency Symbols Range: 20A0–20CF This file contains an excerpt from the character code tables and list of character names for The Unicode Standard, Version 6.3 This file may be changed at any time without notice to reflect errata or other updates to the Unicode Standard. See http://www.unicode.org/errata/ for an up-to-date list of errata. See http://www.unicode.org/charts/ for access to a complete list of the latest character code charts. See http://www.unicode.org/charts/PDF/Unicode-6.3/ for charts showing only the characters added in Unicode 6.3. See http://www.unicode.org/Public/6.3.0/charts/ for a complete archived file of character code charts for Unicode 6.3. Disclaimer These charts are provided as the online reference to the character contents of the Unicode Standard, Version 6.3 but do not provide all the information needed to fully support individual scripts using the Unicode Standard. For a complete understanding of the use of the characters contained in this file, please consult the appropriate sections of The Unicode Standard, Version 6.3, online at http://www.unicode.org/versions/Unicode6.3.0/, as well as Unicode Standard Annexes #9, #11, #14, #15, #24, #29, #31, #34, #38, #41, #42, #44, and #45, the other Unicode Technical Reports and Standards, and the Unicode Character Database, which are available online. See http://www.unicode.org/ucd/ and http://www.unicode.org/reports/ A thorough understanding of the information contained in these additional sources is required for a successful implementation. -

Media Theory and Semiotics: Key Terms and Concepts Binary

Media Theory and Semiotics: Key Terms and Concepts Binary structures and semiotic square of oppositions Many systems of meaning are based on binary structures (masculine/ feminine; black/white; natural/artificial), two contrary conceptual categories that also entail or presuppose each other. Semiotic interpretation involves exposing the culturally arbitrary nature of this binary opposition and describing the deeper consequences of this structure throughout a culture. On the semiotic square and logical square of oppositions. Code A code is a learned rule for linking signs to their meanings. The term is used in various ways in media studies and semiotics. In communication studies, a message is often described as being "encoded" from the sender and then "decoded" by the receiver. The encoding process works on multiple levels. For semiotics, a code is the framework, a learned a shared conceptual connection at work in all uses of signs (language, visual). An easy example is seeing the kinds and levels of language use in anyone's language group. "English" is a convenient fiction for all the kinds of actual versions of the language. We have formal, edited, written English (which no one speaks), colloquial, everyday, regional English (regions in the US, UK, and around the world); social contexts for styles and specialized vocabularies (work, office, sports, home); ethnic group usage hybrids, and various kinds of slang (in-group, class-based, group-based, etc.). Moving among all these is called "code-switching." We know what they mean if we belong to the learned, rule-governed, shared-code group using one of these kinds and styles of language. -

Exchange Rate Statistics

Exchange rate statistics Updated issue Statistical Series Deutsche Bundesbank Exchange rate statistics 2 This Statistical Series is released once a month and pub- Deutsche Bundesbank lished on the basis of Section 18 of the Bundesbank Act Wilhelm-Epstein-Straße 14 (Gesetz über die Deutsche Bundesbank). 60431 Frankfurt am Main Germany To be informed when new issues of this Statistical Series are published, subscribe to the newsletter at: Postfach 10 06 02 www.bundesbank.de/statistik-newsletter_en 60006 Frankfurt am Main Germany Compared with the regular issue, which you may subscribe to as a newsletter, this issue contains data, which have Tel.: +49 (0)69 9566 3512 been updated in the meantime. Email: www.bundesbank.de/contact Up-to-date information and time series are also available Information pursuant to Section 5 of the German Tele- online at: media Act (Telemediengesetz) can be found at: www.bundesbank.de/content/821976 www.bundesbank.de/imprint www.bundesbank.de/timeseries Reproduction permitted only if source is stated. Further statistics compiled by the Deutsche Bundesbank can also be accessed at the Bundesbank web pages. ISSN 2699–9188 A publication schedule for selected statistics can be viewed Please consult the relevant table for the date of the last on the following page: update. www.bundesbank.de/statisticalcalender Deutsche Bundesbank Exchange rate statistics 3 Contents I. Euro area and exchange rate stability convergence criterion 1. Euro area countries and irrevoc able euro conversion rates in the third stage of Economic and Monetary Union .................................................................. 7 2. Central rates and intervention rates in Exchange Rate Mechanism II ............................... 7 II. -

Countries Codes and Currencies 2020.Xlsx

World Bank Country Code Country Name WHO Region Currency Name Currency Code Income Group (2018) AFG Afghanistan EMR Low Afghanistan Afghani AFN ALB Albania EUR Upper‐middle Albanian Lek ALL DZA Algeria AFR Upper‐middle Algerian Dinar DZD AND Andorra EUR High Euro EUR AGO Angola AFR Lower‐middle Angolan Kwanza AON ATG Antigua and Barbuda AMR High Eastern Caribbean Dollar XCD ARG Argentina AMR Upper‐middle Argentine Peso ARS ARM Armenia EUR Upper‐middle Dram AMD AUS Australia WPR High Australian Dollar AUD AUT Austria EUR High Euro EUR AZE Azerbaijan EUR Upper‐middle Manat AZN BHS Bahamas AMR High Bahamian Dollar BSD BHR Bahrain EMR High Baharaini Dinar BHD BGD Bangladesh SEAR Lower‐middle Taka BDT BRB Barbados AMR High Barbados Dollar BBD BLR Belarus EUR Upper‐middle Belarusian Ruble BYN BEL Belgium EUR High Euro EUR BLZ Belize AMR Upper‐middle Belize Dollar BZD BEN Benin AFR Low CFA Franc XOF BTN Bhutan SEAR Lower‐middle Ngultrum BTN BOL Bolivia Plurinational States of AMR Lower‐middle Boliviano BOB BIH Bosnia and Herzegovina EUR Upper‐middle Convertible Mark BAM BWA Botswana AFR Upper‐middle Botswana Pula BWP BRA Brazil AMR Upper‐middle Brazilian Real BRL BRN Brunei Darussalam WPR High Brunei Dollar BND BGR Bulgaria EUR Upper‐middle Bulgarian Lev BGL BFA Burkina Faso AFR Low CFA Franc XOF BDI Burundi AFR Low Burundi Franc BIF CPV Cabo Verde Republic of AFR Lower‐middle Cape Verde Escudo CVE KHM Cambodia WPR Lower‐middle Riel KHR CMR Cameroon AFR Lower‐middle CFA Franc XAF CAN Canada AMR High Canadian Dollar CAD CAF Central African Republic