Inflation in Serbia and in the European Union*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

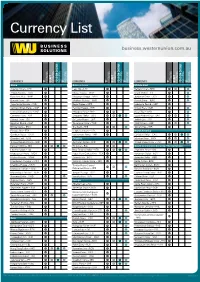

View Currency List

Currency List business.westernunion.com.au CURRENCY TT OUTGOING DRAFT OUTGOING FOREIGN CHEQUE INCOMING TT INCOMING CURRENCY TT OUTGOING DRAFT OUTGOING FOREIGN CHEQUE INCOMING TT INCOMING CURRENCY TT OUTGOING DRAFT OUTGOING FOREIGN CHEQUE INCOMING TT INCOMING Africa Asia continued Middle East Algerian Dinar – DZD Laos Kip – LAK Bahrain Dinar – BHD Angola Kwanza – AOA Macau Pataca – MOP Israeli Shekel – ILS Botswana Pula – BWP Malaysian Ringgit – MYR Jordanian Dinar – JOD Burundi Franc – BIF Maldives Rufiyaa – MVR Kuwaiti Dinar – KWD Cape Verde Escudo – CVE Nepal Rupee – NPR Lebanese Pound – LBP Central African States – XOF Pakistan Rupee – PKR Omani Rial – OMR Central African States – XAF Philippine Peso – PHP Qatari Rial – QAR Comoros Franc – KMF Singapore Dollar – SGD Saudi Arabian Riyal – SAR Djibouti Franc – DJF Sri Lanka Rupee – LKR Turkish Lira – TRY Egyptian Pound – EGP Taiwanese Dollar – TWD UAE Dirham – AED Eritrea Nakfa – ERN Thai Baht – THB Yemeni Rial – YER Ethiopia Birr – ETB Uzbekistan Sum – UZS North America Gambian Dalasi – GMD Vietnamese Dong – VND Canadian Dollar – CAD Ghanian Cedi – GHS Oceania Mexican Peso – MXN Guinea Republic Franc – GNF Australian Dollar – AUD United States Dollar – USD Kenyan Shilling – KES Fiji Dollar – FJD South and Central America, The Caribbean Lesotho Malati – LSL New Zealand Dollar – NZD Argentine Peso – ARS Madagascar Ariary – MGA Papua New Guinea Kina – PGK Bahamian Dollar – BSD Malawi Kwacha – MWK Samoan Tala – WST Barbados Dollar – BBD Mauritanian Ouguiya – MRO Solomon Islands Dollar – -

Exchange Rate Statistics

Exchange rate statistics Updated issue Statistical Series Deutsche Bundesbank Exchange rate statistics 2 This Statistical Series is released once a month and pub- Deutsche Bundesbank lished on the basis of Section 18 of the Bundesbank Act Wilhelm-Epstein-Straße 14 (Gesetz über die Deutsche Bundesbank). 60431 Frankfurt am Main Germany To be informed when new issues of this Statistical Series are published, subscribe to the newsletter at: Postfach 10 06 02 www.bundesbank.de/statistik-newsletter_en 60006 Frankfurt am Main Germany Compared with the regular issue, which you may subscribe to as a newsletter, this issue contains data, which have Tel.: +49 (0)69 9566 3512 been updated in the meantime. Email: www.bundesbank.de/contact Up-to-date information and time series are also available Information pursuant to Section 5 of the German Tele- online at: media Act (Telemediengesetz) can be found at: www.bundesbank.de/content/821976 www.bundesbank.de/imprint www.bundesbank.de/timeseries Reproduction permitted only if source is stated. Further statistics compiled by the Deutsche Bundesbank can also be accessed at the Bundesbank web pages. ISSN 2699–9188 A publication schedule for selected statistics can be viewed Please consult the relevant table for the date of the last on the following page: update. www.bundesbank.de/statisticalcalender Deutsche Bundesbank Exchange rate statistics 3 Contents I. Euro area and exchange rate stability convergence criterion 1. Euro area countries and irrevoc able euro conversion rates in the third stage of Economic and Monetary Union .................................................................. 7 2. Central rates and intervention rates in Exchange Rate Mechanism II ............................... 7 II. -

Countries Codes and Currencies 2020.Xlsx

World Bank Country Code Country Name WHO Region Currency Name Currency Code Income Group (2018) AFG Afghanistan EMR Low Afghanistan Afghani AFN ALB Albania EUR Upper‐middle Albanian Lek ALL DZA Algeria AFR Upper‐middle Algerian Dinar DZD AND Andorra EUR High Euro EUR AGO Angola AFR Lower‐middle Angolan Kwanza AON ATG Antigua and Barbuda AMR High Eastern Caribbean Dollar XCD ARG Argentina AMR Upper‐middle Argentine Peso ARS ARM Armenia EUR Upper‐middle Dram AMD AUS Australia WPR High Australian Dollar AUD AUT Austria EUR High Euro EUR AZE Azerbaijan EUR Upper‐middle Manat AZN BHS Bahamas AMR High Bahamian Dollar BSD BHR Bahrain EMR High Baharaini Dinar BHD BGD Bangladesh SEAR Lower‐middle Taka BDT BRB Barbados AMR High Barbados Dollar BBD BLR Belarus EUR Upper‐middle Belarusian Ruble BYN BEL Belgium EUR High Euro EUR BLZ Belize AMR Upper‐middle Belize Dollar BZD BEN Benin AFR Low CFA Franc XOF BTN Bhutan SEAR Lower‐middle Ngultrum BTN BOL Bolivia Plurinational States of AMR Lower‐middle Boliviano BOB BIH Bosnia and Herzegovina EUR Upper‐middle Convertible Mark BAM BWA Botswana AFR Upper‐middle Botswana Pula BWP BRA Brazil AMR Upper‐middle Brazilian Real BRL BRN Brunei Darussalam WPR High Brunei Dollar BND BGR Bulgaria EUR Upper‐middle Bulgarian Lev BGL BFA Burkina Faso AFR Low CFA Franc XOF BDI Burundi AFR Low Burundi Franc BIF CPV Cabo Verde Republic of AFR Lower‐middle Cape Verde Escudo CVE KHM Cambodia WPR Lower‐middle Riel KHR CMR Cameroon AFR Lower‐middle CFA Franc XAF CAN Canada AMR High Canadian Dollar CAD CAF Central African Republic -

2015 / DEFI 15-08 Detection of Implicit Fluctuation Bands and Their

DOCUMENTOS DE ECONOMÍA Y FINANZAS INTERNACIONALES Working Papers on International Economics and Finance DEFI 15-08 May 2015 Detection of Implicit Fluctuation Bands and their Credibility in Candidate Countries Simón Sosvilla-Rivero María del Carmen Ramos Herrera Asociación Española de Economía y Finanzas Internacionales www.aeefi.com ISSN: 1696-6376 Detection of Implicit Fluctuation Bands and their Credibility in Candidate Countries SIMÓN SOSVILLA-RIVERO Universidad Complutense de Madrid, Facultad de Ciencias Económicas y Empresariales Campus de Somosaguas, 28223, Madrid, Spain. MARÍA DEL CARMEN RAMOS-HERRERA Universidad Complutense de Madrid, Facultad de Ciencias Económicas y Empresariales Campus de Somosaguas, 28223, Madrid, Spain. e-mail: [email protected] Abstract: This paper attempts to identify implicit exchange rate regimes for currencies of candidate countries vis-à-vis the euro. To that end, we apply three sequential procedures that consider the dynamics of exchange rates to data covering the period from 1999:01 to 2012:12. Our results would suggest that implicit bands have existed in many sub-periods for almost all currencies under study. Once we detect de facto discrepancies between de facto and de iure exchange rate regimes, we make use of different methods to study the credibility of the detected fluctuation bands. The detected lack of credibility in a high percentage of the sample is robust using the Drift Adjustment method and discrete choice models, suggesting that economic agents do not behave as if these bands actually were in force at time of making their financial plans. These countries do not improve the confidence on the fluctuation bands as time evolves. -

WM/Refinitiv Closing Spot Rates

The WM/Refinitiv Closing Spot Rates The WM/Refinitiv Closing Exchange Rates are available on Eikon via monitor pages or RICs. To access the index page, type WMRSPOT01 and <Return> For access to the RICs, please use the following generic codes :- USDxxxFIXz=WM Use M for mid rate or omit for bid / ask rates Use USD, EUR, GBP or CHF xxx can be any of the following currencies :- Albania Lek ALL Austrian Schilling ATS Belarus Ruble BYN Belgian Franc BEF Bosnia Herzegovina Mark BAM Bulgarian Lev BGN Croatian Kuna HRK Cyprus Pound CYP Czech Koruna CZK Danish Krone DKK Estonian Kroon EEK Ecu XEU Euro EUR Finnish Markka FIM French Franc FRF Deutsche Mark DEM Greek Drachma GRD Hungarian Forint HUF Iceland Krona ISK Irish Punt IEP Italian Lira ITL Latvian Lat LVL Lithuanian Litas LTL Luxembourg Franc LUF Macedonia Denar MKD Maltese Lira MTL Moldova Leu MDL Dutch Guilder NLG Norwegian Krone NOK Polish Zloty PLN Portugese Escudo PTE Romanian Leu RON Russian Rouble RUB Slovakian Koruna SKK Slovenian Tolar SIT Spanish Peseta ESP Sterling GBP Swedish Krona SEK Swiss Franc CHF New Turkish Lira TRY Ukraine Hryvnia UAH Serbian Dinar RSD Special Drawing Rights XDR Algerian Dinar DZD Angola Kwanza AOA Bahrain Dinar BHD Botswana Pula BWP Burundi Franc BIF Central African Franc XAF Comoros Franc KMF Congo Democratic Rep. Franc CDF Cote D’Ivorie Franc XOF Egyptian Pound EGP Ethiopia Birr ETB Gambian Dalasi GMD Ghana Cedi GHS Guinea Franc GNF Israeli Shekel ILS Jordanian Dinar JOD Kenyan Schilling KES Kuwaiti Dinar KWD Lebanese Pound LBP Lesotho Loti LSL Malagasy -

Serbia Euro-Asia Unitary Country

SERBIA EURO-ASIA UNITARY COUNTRY Basic socio-economic indicators Income group - UPPER MIDDLE INCOME Local currency - SERBIAN DINAR (RSD) Population and geography Economic data AREA: 77 474 km2 GDP: 96.9 billion (current PPP international dollars) i.e. 13 592 dollars per inhabitant (2014) POPULATION: million inhabitants (2014), 7.129 REAL GDP GROWTH: -1.8% (2014 vs 2013) a decrease of 0.6 % per year (2010-2014) UNEMPLOYMENT RATE: 18.9% (2014) 2 DENSITY: 92 inhabitants/km FOREIGN DIRECT INVESTMENT, NET INFLOWS (FDI): 2 000 (BoP, current USD millions, 2014) URBAN POPULATION: 55.6% of national population GROSS FIXED CAPITAL FORMATION (GFCF): 15.6% of GDP (2014) CAPITAL CITY: Belgrade (16.6% of national population) HUMAN DEVELOPMENT INDEX: 0.771 (high), rank 66 Sources: World Bank Development Indicators, UNDP-HDI, ILO Territorial organisation and subnational government RESPONSIBILITIES MUNICIPAL LEVEL INTERMEDIATE LEVEL REGIONAL OR STATE LEVEL TOTAL NUMBER OF SNGs 174 - 2 176 23 Cities (grad) and 2 Autonomous Provinces 150 Municipalities (opstina) (Pokrajine Vojvodina + City of Belgrade aND Kosovo and Metohija) Average municipal size: 40 805 inhabitantS Main features of territorial organisation. Serbia is a unitary country with a one tier structure of government. This tier is composed by 150 municipalities (opstina), 23 Cities (grad) and the City of Belgrade, which are themselves divided into several subordinate administrative units (mesna zajednica). Municipalities (usually>10000hab), has an assembly, public service property and a budget. They comprise local communities. Cities (>100000) have an assembly and budget of its own. Municipalities and cities are gathered into larger entities known as districts which are regional centers of state authority. -

Exchange Rate Statistics

Exchange rate statistics Updated issue Statistical Series Deutsche Bundesbank Exchange rate statistics 2 This Statistical Series is released once a month and pub- Deutsche Bundesbank lished on the basis of Section 18 of the Bundesbank Act Wilhelm-Epstein-Straße 14 (Gesetz über die Deutsche Bundesbank). 60431 Frankfurt am Main Germany To be informed when new issues of this Statistical Series are published, subscribe to the newsletter at: Postfach 10 06 02 www.bundesbank.de/statistik-newsletter_en 60006 Frankfurt am Main Germany Compared with the regular issue, which you may subscribe to as a newsletter, this issue contains data, which have Tel.: +49 (0)69 9566 3512 been updated in the meantime. Email: www.bundesbank.de/contact Up-to-date information and time series are also available Information pursuant to Section 5 of the German Tele- online at: media Act (Telemediengesetz) can be found at: www.bundesbank.de/content/821976 www.bundesbank.de/imprint www.bundesbank.de/timeseries Reproduction permitted only if source is stated. Further statistics compiled by the Deutsche Bundesbank can also be accessed at the Bundesbank web pages. ISSN 2699–9188 A publication schedule for selected statistics can be viewed Please consult the relevant table for the date of the last on the following page: update. www.bundesbank.de/statisticalcalender Deutsche Bundesbank Exchange rate statistics 3 Contents I. Euro area and exchange rate stability convergence criterion 1. Euro area countries and irrevoc able euro conversion rates in the third stage of Economic and Monetary Union .................................................................. 7 2. Central rates and intervention rates in Exchange Rate Mechanism II ............................... 7 II. -

The Big Reset: War on Gold and the Financial Endgame

WILL s A system reset seems imminent. The world’s finan- cial system will need to find a new anchor before the year 2020. Since the beginning of the credit s crisis, the US realized the dollar will lose its role em as the world’s reserve currency, and has been planning for a monetary reset. According to Willem Middelkoop, this reset MIDD Willem will be designed to keep the US in the driver’s seat, allowing the new monetary system to include significant roles for other currencies such as the euro and China’s renminbi. s Middelkoop PREPARE FOR THE COMING RESET E In all likelihood gold will be re-introduced as one of the pillars LKOOP of this next phase in the global financial system. The predic- s tion is that gold could be revalued at $ 7,000 per troy ounce. By looking past the American ‘smokescreen’ surrounding gold TWarh on Golde and the dollar long ago, China and Russia have been accumu- lating massive amounts of gold reserves, positioning them- THE selves for a more prominent role in the future to come. The and the reset will come as a shock to many. The Big Reset will help everyone who wants to be fully prepared. Financial illem Middelkoop (1962) is founder of the Commodity BIG Endgame Discovery Fund and a bestsell- s ing author, who has been writing about the world’s financial system since the early 2000s. Between 2001 W RESET and 2008 he was a market commentator for RTL Television in the Netherlands and also BIG appeared on CNBC. -

Currency List

Americas & Caribbean | Tradeable Currency Breakdown Currency Currency Name New currency/ Buy Spot Sell Spot Deliverable Non-Deliverable Special requirements/ Symbol Capability Forward Forward Restrictions ANG Netherland Antillean Guilder ARS Argentine Peso BBD Barbados Dollar BMD Bermudian Dollar BOB Bolivian Boliviano BRL Brazilian Real BSD Bahamian Dollar CAD Canadian Dollar CLP Chilean Peso CRC Costa Rica Colon DOP Dominican Peso GTQ Guatemalan Quetzal GYD Guyana Dollar HNL Honduran Lempira J MD J amaican Dollar KYD Cayman Islands MXN Mexican Peso NIO Nicaraguan Cordoba PEN Peruvian New Sol PYG Paraguay Guarani SRD Surinamese Dollar TTD Trinidad/Tobago Dollar USD US Dollar UYU Uruguay Peso XCD East Caribbean Dollar 130 Old Street, EC1V 9BD, London | t. +44 (0) 203 475 5301 | [email protected] sugarcanecapital.com Europe | Tradeable Currency Breakdown Currency Currency Name New currency/ Buy Spot Sell Spot Deliverable Non-Deliverable Special requirements/ Symbol Capability Forward Forward Restrictions ALL Albanian Lek BGN Bulgarian Lev CHF Swiss Franc CZK Czech Koruna DKK Danish Krone EUR Euro GBP Sterling Pound HRK Croatian Kuna HUF Hungarian Forint MDL Moldovan Leu NOK Norwegian Krone PLN Polish Zloty RON Romanian Leu RSD Serbian Dinar SEK Swedish Krona TRY Turkish Lira UAH Ukrainian Hryvnia 130 Old Street, EC1V 9BD, London | t. +44 (0) 203 475 5301 | [email protected] sugarcanecapital.com Middle East | Tradeable Currency Breakdown Currency Currency Name New currency/ Buy Spot Sell Spot Deliverabl Non-Deliverabl Special Symbol Capability e Forward e Forward requirements/ Restrictions AED Utd. Arab Emir. Dirham BHD Bahraini Dinar ILS Israeli New Shekel J OD J ordanian Dinar KWD Kuwaiti Dinar OMR Omani Rial QAR Qatar Rial SAR Saudi Riyal 130 Old Street, EC1V 9BD, London | t. -

CURRENCY BOARD FINANCIAL STATEMENTS Currency Board Working Paper

SAE./No.22/December 2014 Studies in Applied Economics CURRENCY BOARD FINANCIAL STATEMENTS Currency Board Working Paper Nicholas Krus and Kurt Schuler Johns Hopkins Institute for Applied Economics, Global Health, and Study of Business Enterprise & Center for Financial Stability Currency Board Financial Statements First version, December 2014 By Nicholas Krus and Kurt Schuler Paper and accompanying spreadsheets copyright 2014 by Nicholas Krus and Kurt Schuler. All rights reserved. Spreadsheets previously issued by other researchers are used by permission. About the series The Studies in Applied Economics of the Institute for Applied Economics, Global Health and the Study of Business Enterprise are under the general direction of Professor Steve H. Hanke, co-director of the Institute ([email protected]). This study is one in a series on currency boards for the Institute’s Currency Board Project. The series will fill gaps in the history, statistics, and scholarship of currency boards. This study is issued jointly with the Center for Financial Stability. The main summary data series will eventually be available in the Center’s Historical Financial Statistics data set. About the authors Nicholas Krus ([email protected]) is an Associate Analyst at Warner Music Group in New York. He has a bachelor’s degree in economics from The Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, where he also worked as a research assistant at the Institute for Applied Economics and the Study of Business Enterprise and did most of his research for this paper. Kurt Schuler ([email protected]) is Senior Fellow in Financial History at the Center for Financial Stability in New York. -

List of Currencies of All Countries

The CSS Point List Of Currencies Of All Countries Country Currency ISO-4217 A Afghanistan Afghan afghani AFN Albania Albanian lek ALL Algeria Algerian dinar DZD Andorra European euro EUR Angola Angolan kwanza AOA Anguilla East Caribbean dollar XCD Antigua and Barbuda East Caribbean dollar XCD Argentina Argentine peso ARS Armenia Armenian dram AMD Aruba Aruban florin AWG Australia Australian dollar AUD Austria European euro EUR Azerbaijan Azerbaijani manat AZN B Bahamas Bahamian dollar BSD Bahrain Bahraini dinar BHD Bangladesh Bangladeshi taka BDT Barbados Barbadian dollar BBD Belarus Belarusian ruble BYR Belgium European euro EUR Belize Belize dollar BZD Benin West African CFA franc XOF Bhutan Bhutanese ngultrum BTN Bolivia Bolivian boliviano BOB Bosnia-Herzegovina Bosnia and Herzegovina konvertibilna marka BAM Botswana Botswana pula BWP 1 www.thecsspoint.com www.facebook.com/thecsspointOfficial The CSS Point Brazil Brazilian real BRL Brunei Brunei dollar BND Bulgaria Bulgarian lev BGN Burkina Faso West African CFA franc XOF Burundi Burundi franc BIF C Cambodia Cambodian riel KHR Cameroon Central African CFA franc XAF Canada Canadian dollar CAD Cape Verde Cape Verdean escudo CVE Cayman Islands Cayman Islands dollar KYD Central African Republic Central African CFA franc XAF Chad Central African CFA franc XAF Chile Chilean peso CLP China Chinese renminbi CNY Colombia Colombian peso COP Comoros Comorian franc KMF Congo Central African CFA franc XAF Congo, Democratic Republic Congolese franc CDF Costa Rica Costa Rican colon CRC Côte d'Ivoire West African CFA franc XOF Croatia Croatian kuna HRK Cuba Cuban peso CUC Cyprus European euro EUR Czech Republic Czech koruna CZK D Denmark Danish krone DKK Djibouti Djiboutian franc DJF Dominica East Caribbean dollar XCD 2 www.thecsspoint.com www.facebook.com/thecsspointOfficial The CSS Point Dominican Republic Dominican peso DOP E East Timor uses the U.S. -

Belgrade, Serbia Destination Guide

Belgrade, Serbia Destination Guide Overview of Belgrade Belgrade has developed into a prominent European capital, its promising growth and optimism seeking to overshadow its turbulent past. The history of Belgrade goes back some 6,000 years, and is filled with tales of conflict and tragedy. But no matter the cost or devastation, the city has always bounced back and is in the midst of a cultural and creative revival. Situated where the Sava and Danube rivers meet on the Balkan Peninsula, the beauty and charm of the city is not found in gorgeous buildings or sweeping parks. Instead, it beats with an identity layered with relics of many generations and the remaining customs of countless invaders. Decidedly Old World with a hint of the Orient, varying cultural influences and architectural styles jostle for attention in Belgrade, combining to imbue the modern city with its own unique aura. The best place to begin understanding the city is at the site of its original ancient settlement, the hill called Kalemegdan, now a fascinating park-like complex of historic structures overlooking the Old Town (Stari Grad). Here, the Military Museum traces the history of the city's bloody past, from its first conflict with the Roman legions in the 1st century BC to its most recent conflagration, when NATO forces bombed the city for 78 straight days in 1999. Those less fascinated by history and who would rather enjoy modern Belgrade will find myriad leisure and pleasure opportunities in the city. From the techno scene of its famed nightclubs to the restaurants and street performances of bohemian Skadarlija Street, visitors to Belgrade will feel welcomed by the warm and proud residents of this indomitable city.