Technologies of Piracy? Exploring the Interplay Between Commercialism and Idealism in the Development of MP3 and Divx

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Zvukový Formát Mp3

UNIVERZITA PARDUBICE DOPRAVNÍ FAKULTA JANA PERNERA KATEDRA ELEKTROTECHNIKY, ELEKTRONIKY A ZABEZPEČOVACÍ TECHNIKY V DOPRAVĚ ZVUKOVÝ FORMÁT MP3 BAKALÁŘSKÁ PRÁCE AUTOR PRÁCE: Petr Gregar VEDOUCÍ PRÁCE: RNDr. Jan Hula 2007 UNIVERZITY OF PARDUBICE JAN PERNER TRAFFIC FACULTY DEPARTMENT OF ELECTRICAL AND ELECTRONICAL ENGINEERING AND SIGNALLING IN TRANSPORT SOUND FORMAT MP3 BACHELOR WORK AUTOR: Petr Gregar SUPERVIZOR: RNDr. Jan Hula 2007 PROHLÁŠENÍ Tuto práci jsem vypracoval samostatně. Veškeré literární prameny a informace, které jsem v práci využil, jsou uvedeny v seznamu použité literatury. Byl jsem seznámen s tím, že se na moji práci vztahují práva a povinnosti vyplývající ze zákona č. 121/2000 Sb., autorský zákon, zejména se skutečností, že Univerzita Pardubice má právo na uzavření licenční smlouvy o užití této práce jako školního díla podle § 60 odst. 1 autorského zákona, a s tím, že pokud dojde k užití této práce mnou nebo bude poskytnuta licence o užití jinému subjektu, je Univerzita Pardubice oprávněna ode mne požadovat přiměřený příspěvek na úhradu nákladů, které na vytvoření díla vynaložila, a to podle okolností až do jejich skutečné výše. Souhlasím s prezenčním zpřístupněním své práce v Univerzitní knihovně Univerzity Pardubice. V Pardubicích dne 8. 5. 2007 …..…………………………… Petr Grgear SOUHRN Bakalářská práce se zabývá popisem kódování digitálně uložených zvukových dat podle standardu MPEG – 1 Layer III (MP3) a strukturou takto vytvořeného souboru. V úvodní části jsou popsány základní pojmy jako zvuk, vnímání zvuků lidským uchem, způsob záznamu zvuku v číslicové formě či princip reprodukce zvuku. Druhá část se věnuje historii formátu od počátků jeho vývoje až do současnosti. Následuje vlastní popis standardu MP3. Významnou výhodou formátu MP3 jsou i tzv. -

Analisis Implantación Software Libre

Libro Blanco Software libre en España. Libro Blanco del Software Libre en España 2003 Derecho de Autor © A.Abella, J. Sánchez, R.Santos y M.A.Segovia Permiso para copiar, distribuir y/o modificar este documento bajo los términos de la Licencia de Documentación Libre GNU, Versión 2 o cualquier otra versión posterior publicada por la Free Software Foundation; con las Secciones Invariantes 1. Principales conclusiones 2. Pan, piedras y software libre 3. Repercusión socioeconómica del software libre 4. El futuro del software libre en España 5. Desafíos a superar por el software libre y siendo Libro Blanco software libre en España 2003 el texto de la Cubierta Frontal, y sin texto de la Cubierta Posterior. Una copia de la licencia es incluida en la sección titulada "Licencia de Documentación Libre GNU". 2003© A.Abella, J.Sanchez, R.Santos y M.A. Segovia Libro Blanco software libre en España 2003. Versión 0.997-2003 1.Objetivo del libro blanco .....................................................................6 2.Conclusiones del libro blanco .............................................................7 Conclusiones generales.................................................................................7 Conclusiones políticas....................................................................................8 Conclusiones técnicas y empresariales.......................................................9 3.Patrocinadores ...................................................................................11 4.Introducción. El software y el software -

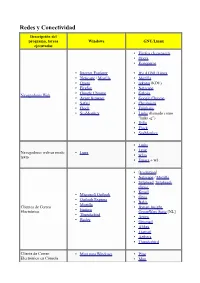

Introducción a Linux Equivalencias Windows En Linux Ivalencias

No has iniciado sesión Discusión Contribuciones Crear una cuenta Acceder Página discusión Leer Editar Ver historial Buscar Introducción a Linux Equivalencias Windows en Linux Portada < Introducción a Linux Categorías de libros Equivalencias Windows en GNU/Linux es una lista de equivalencias, reemplazos y software Cam bios recientes Libro aleatorio análogo a Windows en GNU/Linux y viceversa. Ayuda Contenido [ocultar] Donaciones 1 Algunas diferencias entre los programas para Windows y GNU/Linux Comunidad 2 Redes y Conectividad Café 3 Trabajando con archivos Portal de la comunidad 4 Software de escritorio Subproyectos 5 Multimedia Recetario 5.1 Audio y reproductores de CD Wikichicos 5.2 Gráficos 5.3 Video y otros Imprimir/exportar 6 Ofimática/negocios Crear un libro 7 Juegos Descargar como PDF Versión para im primir 8 Programación y Desarrollo 9 Software para Servidores Herramientas 10 Científicos y Prog s Especiales 11 Otros Cambios relacionados 12 Enlaces externos Subir archivo 12.1 Notas Páginas especiales Enlace permanente Información de la Algunas diferencias entre los programas para Windows y y página Enlace corto GNU/Linux [ editar ] Citar esta página La mayoría de los programas de Windows son hechos con el principio de "Todo en uno" (cada Idiomas desarrollador agrega todo a su producto). De la misma forma, a este principio le llaman el Añadir enlaces "Estilo-Windows". Redes y Conectividad [ editar ] Descripción del programa, Windows GNU/Linux tareas ejecutadas Firefox (Iceweasel) Opera [NL] Internet Explorer Konqueror Netscape / -

![[Amok] S/N: 1299275 a Smaller Note 99 2.08 Firstname](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4079/amok-s-n-1299275-a-smaller-note-99-2-08-firstname-1924079.webp)

[Amok] S/N: 1299275 a Smaller Note 99 2.08 Firstname

LETRA A A Real Validator 1.01 Name: ubique.daemon [AmoK] s/n: 1299275 A Smaller Note 99 2.08 FirstName: ViKiNG LastName: Crackz Company: private Street: ViKiNG Zip: 11111 City: Crackz Code: 19147950 Order: 97234397 A.I.D 2.1 s/n: AD6778-A2G0 A.I.D. 2.0.2 s/n: AD6778-A2G0T A+ Math 1.0 Name: (Anything) s/n: 8826829 A+ MathMAT 1.0.0 Name: TEAM ElilA s/n: 8826829 A-1 Image Screen Saver 4.1 s/n: B5K7ij49p2 A1 Text Finder 4.02 s/n: PCSLT3248034 ABCPager 1.6.4 Name: Sara s/n: 1DQDSSSSSSSS ABCPager Plus 5.0.5 Name: Sara s/n: M5N5SSSSSSSS Ability Office 2000 2.0.007 Name: Ben Hooks s/n: 12878044-01034-40997 Ability Office 2000 2.0.005 Name:Nemesis] Organization:TNT s/n: 15155445-37898- 08511 Ablaze Quick Viewer 1.6 Name: Hazard s/n: 81261184XXXXXXX Abritus Business 2000 3.02 Name/Company: (Anything) s/n: 1034-314-102 Abritus Business 2000 3.02 Name/Company: (Anything) s/n: 1034-314-102 Absolute Fast Taskbar 1.01 Name: (Anything) s/n: nxpwvy Absolute Security 3.6 Name: Evil Ernie 2K [SCB] s/n: GMKKRAPZBJRRXQP Absolute Security Pro 3.3 Name: C0ke2000 s/n: GPBKTCNKYZKWQPJ Absolute Security Standard 3.4 Name: Hazard 2000 s/n: ECHVNZQRCYEHHBB or Name: PhatAzz [e!] s/n: RBFXPLUMBPGDFYW Absolute Security Standard 3.5 Name: embla of phrozen crew s/n: LTPDTDMAEHNKNTR AbsoluteFTP 1.0 beta 6 Name: CORE/JES Company: CORE s/n: 00-00-000000 Exp: never Key: 1074 2875 9697 3324 3564 AbsoluteFTP 1.0 Final Name: CORE/JES Company: CORE s/n: 00-00-000000 Exp: Never Key: 1074 2875 9697 3324 3564 AbsoluteFTP 1.0 RC 11 Name: _RudeBoy_ Company: Phrozen Crew s/n: 02-01- -

Bibliotecas De Edição Disponíveis Nos Softwares Editores De Áudio

Josseimar Altissimo Conrad Bibliotecas de edição disponíveis nos softwares editores de áudio Ijuí 2014 Josseimar Altissimo Conrad Bibliotecas de edição disponíveis nos softwares editores de áudio Trabalho apresentado ao curso de Ciência da Computação da Universidade Regional do No- roeste do Estado do Rio Grande do Sul , como requisito para a obtenção do título de Bacharel em Ciência da Computação. Universidade Regional Do Noroeste Do Estado Do Rio Grande Do Sul Departamento Das Ciências Exatas E Engenharias Ciência Da Computação Orientador: Edson Luiz Padoin Ijuí 2014 Josseimar Altissimo Conrad Bibliotecas de edição disponíveis nos softwares editores de áudio Trabalho apresentado ao curso de Ciência da Computação da Universidade Regional do No- roeste do Estado do Rio Grande do Sul , como requisito para a obtenção do título de Bacharel em Ciência da Computação. Trabalho aprovado. Ijuí, ( ) de dezembro de 2014: Edson Luiz Padoin Orientador Rogério Samuel de Moura Martins Convidado Ijuí 2014 Dedico este trabalho primeiramente a Deus, pois sem Ele, nada seria possível e não estaríamos aqui reunidos, desfrutando, juntos, destes momentos que nos são tão importantes. Aos meus pais Ilvo Conrad e Rosani Altissimo Conrad; pelo esforço, dedicação e compreensão, em todos os momentos desta e de outras caminhadas.. Agradecimentos Primeiramente a Deus pois ele deu a permissão para tudo isso acontecer, no decorrer da minha vida, e não somente nestes anos como universitário, mas em todos os momentos é o maior mestre que alguém pode conhecer. A esta universidade, seu corpo docente, direção e administração que oportunizaram a janela que hoje vislumbro um horizonte superior, eivado pela acendrada confiança no mérito e ética aqui presentes. -

A Multi-Level Perspective Analysis of the Change in Music Consumption 1989-2014

A multi-level perspective analysis of the change in music consumption 1989-2014 by Richard Samuels Thesis submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Geography and Planning Cardiff University 2018 i Abstract This thesis seeks to examine the historical socio-technical transitions in the music industry through the 1990s and 2000s which fundamentally altered the way in which music is consumed along with the environmental resource impact of such transitions. Specifically, the investigation seeks to establish a historical narrative of events that are significant to the story of this transition through the use of the multi-level perspective on socio-technical transitions as a framework. This thesis adopts a multi-level perspective for socio-technical transitions approach to analyse this historical narrative seeking to identify key events and actors that influenced the transition as well as enhance the methodological implementation of the multi-level perspective. Additionally, this thesis utilised the Material Intensity Per Service unit methodology to derive several illustrative scenarios of music consumption and their associated resource usage to establish whether the socio-technical transitions experienced by the music industry can be said to be dematerialising socio-technical transitions. This thesis provides a number of original empirical and theoretical contributions to knowledge. This is achieved by presenting a multi-level perspective analysis of a historical narrative established using over 1000 primary sources. The research identifies, examines and discusses key events, actors and transition pathways denote the complex nature of dematerialising socio-technical systems as well as highlights specifically the influence different actors and actor groups can have on the pathways that transitions take. -

Univerzita Palackého V Olomouci Filozofická Fakulta

UNIVERZITA PALACKÉHO V OLOMOUCI FILOZOFICKÁ FAKULTA MAGISTERSKÁ DIPLOMOVÁ PRÁCE ONDŘEJ GRZEGORZ UNIVERZITA PALACKÉHO V OLOMOUCI FILOZOFICKÁ FAKULTA KATEDRA MUZIKOLOGIE FENOMÉN DIGITÁLNÍHO ZVUKOVÉHO ZÁZNAMU NA PŘÍKLADU OLOMOUCKÉHO STUDIA ČESKÉHO ROZHLASU autor: Bc. Ondřej Grzegorz vedoucí práce: Mgr. Petr Lyko, PhD. PALACKÝ UNIVERSITY OLOMOUC PHILOSOPHICAL FACULTY DEPARTMENT OF MUSICOLOGY THE DIGITAL AUDIO RECORDING PHENOMENON IN A CASE OF THE OLOMOUC RADIO STATION author: Bc. Ondřej Grzegorz supervisor: Mgr. Petr Lyko, Ph.D. Prohlašuji, že předložená práce je mým původním autorským dílem, které jsem vypracoval samostatně. Veškerou literaturu a další zdroje, z nichž jsem při zpracování čerpal, v práci řádně cituji a jsou uvedeny v seznamu použité literatury. V Ostravě ……….... …………………………………... Beru na vědomí, že diplomová práce je majetkem Univerzity Palackého v Olomouci (autorský zákon č. 121/2000 Sb., § 60 odst. 1), bez jejího souhlasu nesmí být nic z obsahu publikováno. Souhlasím s prezenčním zpřístupněním své práce v Knihovně Univerzity Palackého a k poskytnutí práce do celostátní databáze diplomových prací. Naopak nesouhlasím s kopírováním částí práce bez předchozího souhlasu. Poděkování: Děkuji vedoucímu práce Petru Lykovi za užitečné rady a připomínky k obsahu práce. Děkuji profesoru Ivanu Poledňákovi in memoriam za schválení námětu práce a inspiraci. Dále děkuji kolektivu Českého rozhlasu Olomouc za ochotnou spolupráci a Romanu Grzegorzovi a Haně Grzegorzové za nezištnou podporu. Obsah Úvod .....................................................................................................1 -

Naslov Završnog Rada

Agregator internetskih radijskih postaja Rakuša, Juraj Undergraduate thesis / Završni rad 2018 Degree Grantor / Ustanova koja je dodijelila akademski / stručni stupanj: University North / Sveučilište Sjever Permanent link / Trajna poveznica: https://urn.nsk.hr/urn:nbn:hr:122:120665 Rights / Prava: In copyright Download date / Datum preuzimanja: 2021-09-26 Repository / Repozitorij: University North Digital Repository Završni rad br. 606/MM/2018 Agregator internetskih radijskih postaja Juraj Rakuša, 0810/336 Varaždin, listopad 2018. godine Odjel za Multimediju, oblikovanje i primjenu Završni rad br. 606/MM/2018 Agregator internetskih radijskih postaja Student Juraj Rakuša, 0810/336 Mentor dr. sc. Domagoj Frank, pred. Varaždin, listopad 2018. godine Predgovor Upisom na Sveučilište Sjever 2015. godine, upustio sam se u jednu veliku avanturu koje na samom početku nisam bio niti svjestan. Prednosti i mane samostalnog života u drugome gradu pokazale su se već u prvih nekoliko mjeseci studija. Uz svaki loš bilo je deset dobrih trenutaka pa mogu reći da sam u zadnje tri godine stvarno uživao. Ne samo da mi je ovaj način života u Varaždinu pružio jedno veliko iskustvo, već me je i potaknuo da ovako nastavim i krenem u budućnost pozitivniji nego prije. Zauvijek ću biti zadovoljan sa svime što sam iskusio studirajući na Sjeveru te mi je drago što će mi ovo iskustvo pomoći u izgradnji buduće karijere i života. Izrada ovog rada pružila mi je šansu za istraživanje, meni osobno, vrlo zanimljivog područja. Time bih se volio zahvaliti svom mentoru, predavaču Domagoju Franku, ali i ostalim profesorima koji su se tijekom zadnje tri godine trudili da moje kolege i mene nauče i potaknu na rad koji nas zanima. -

Redes Y Conectividad Descripción Del Programa, Tareas Windows GNU/Linux Ejecutadas • Firefox (Iceweasel) • Opera • Konqueror

Redes y Conectividad Descripción del programa, tareas Windows GNU/Linux ejecutadas • Firefox (Iceweasel) • Opera • Konqueror • Internet Explorer • IEs 4 GNU/Linux • Netscape / Mozilla • Mozilla • Opera • rekonq (KDE) • Firefox • Netscape • Google Chrome • Galeón Navegadores Web • Avant Browser • Google Chrome • Safari • Chromium • Flock • Epiphany • SeaMonkey • Links (llamado como "links -g") • Dillo • Flock • SeaMonkey • Links • • Lynx Navegadores web en modo Lynx • texto w3m • Emacs + w3. • [Evolution] • Netscape / Mozilla • Sylpheed , Sylpheed- claws. • Kmail • Microsoft Outlook • Gnus • Outlook Express • Balsa • Mozilla Clientes de Correo • Bynari Insight • Eudora Electrónico GroupWare Suite [NL] • Thunderbird • Arrow • Becky • Gnumail • Althea • Liamail • Aethera • Thunderbird Cliente de Correo • Mutt para Windows • Pine Electrónico en Cónsola • Mutt • Gnus • de , Pine para Windows • Elm. • Xemacs • Liferea • Knode. • Pan • Xnews , Outlook, • NewsReader Lector de noticias Netscape / Mozilla • Netscape / Mozilla. • Sylpheed / Sylpheed- claws • MultiGet • Orbit Downloader • Downloader para X. • MetaProducts Download • Caitoo (former Kget). Express • Prozilla . • Flashget • wxDownloadFast . • Go!zilla • Kget (KDE). Gestor de Descargas • Reget • Wget (console, standard). • Getright GUI: Kmago, QTget, • Wget para Windows Xget, ... • Download Accelerator Plus • Aria. • Axel. • Httrack. • WWW Offline Explorer. • Wget (consola, estándar). GUI: Kmago, QTget, Extractor de Sitios Web Teleport Pro, Webripper. Xget, ... • Downloader para X. • -

Mp3

<d.w.o> mp3 book: Table of Contents <david.weekly.org> January 4 2002 mp3 book Table of Contents Table of Contents auf deutsch en español {en français} Chapter 0: Introduction <d.w.o> ● What's In This Book about ● Who This Book Is For ● How To Read This Book books Chapter 1: The Hype code codecs ● What Is Internet Audio and Why Do People Use It? mp3 book ● Some Thoughts on the New Economy ● A Brief History of Internet Audio news ❍ Bell Labs, 1957 - Computer Music Is Born pictures ❍ Compression in Movies & Radio - MP3 is Invented! poems ❍ The Net Circa 1996: RealAudio, MIDI, and .AU projects ● The MP3 Explosion updates ❍ 1996 - The Release ❍ 1997 - The Early Adopters writings ❍ 1998 - The Explosion video ❍ sidebar - The MP3 Summit get my updates ❍ 1999 - Commercial Acceptance ● Why Did It Happen? ❍ Hardware ❍ Open Source -> Free, Convenient Software ❍ Standards ❍ Memes: Idea Viruses ● Conclusion page source http://david.weekly.org/mp3book/toc.php3 (1 of 6) [1/4/2002 10:53:06 AM] <d.w.o> mp3 book: Table of Contents Chapter 2: The Guts of Music Technology ● Digital Audio Basics ● Understanding Fourier ● The Biology of Hearing ● Psychoacoustic Masking ❍ Normal Masking ❍ Tone Masking ❍ Noise Masking ● Critical Bands and Prioritization ● Fixed-Point Quantization ● Conclusion Chapter 3: Modern Audio Codecs ● MPEG Evolves ❍ MP2 ❍ MP3 ❍ AAC / MPEG-4 ● Other Internet Audio Codecs ❍ AC-3 / Dolbynet ❍ RealAudio G2 ❍ VQF ❍ QDesign Music Codec 2 ❍ EPAC ● Summary Chapter 4: The New Pipeline: The New Way To Produce, Distribute, and Listen to Music ● Digital -

Tabla De Equivalencias De Programas Propietarios Y De Software Libre

ENTORNO PC: TABLA DE EQUIVALENCIAS DE PROGRAMAS PROPIETARIOS Y DE SOFTWARE LIBRE. *PRÓPOSITO. En este documento, se detallan en el momento actual, una tabla de equivalencia de software usado en Windows y software libre. Esta tabla no es estática y está en continuo cambio según se va produciendo software y pasándolo a las licencias libres. En cualquier caso, en la siguiente dirección web, se encuentra una exhaustiva lista de posibilidades: http://linuxshop.ru/linuxbegin/win-lin-soft-spanish/ Notas: · Por principio todos los programas de linux en esta tabla son libres y están liberados. Los programas propietarios para Linux están marcados con una señal [Prop]. Programa, tareas Windows Linux ejecutadas 1) Redes y Conectividad. 1) Netscape / Mozilla . 2) Galeon. 3) Konqueror. Internet Explorer, 4) Opera. [Prop] Netscape / Mozilla for Navegadores Web 5) Phoenix. Windows, Opera, 6) Nautilus. Phoenix for Windows, ... 7) Epiphany. 8) Links. (with "-g" key). 9) Dillo. (Parches lenguaje Ruso - aquí). 1) Links. Navegadores web para 2) Lynx. Lynx para Windows Consola 3) w3m. 4) Xemacs + w3. 1) Evolution. 2) Netscape / Mozilla messenger. 3) Sylpheed, Sylpheed-claws. 4) Kmail. 5) Gnus. Outlook Express, Mozilla 6) Balsa. Clientes de Email for Windows, Eudora, 7) Bynari Insight GroupWare Suite. Becky [Prop] 8) Arrow. 9) Gnumail. 10) Althea. 11) Liamail. 12) Aethera. 1 1) Evolution. Clientes de email al estilo 2) Bynari Insight GroupWare Suite. Outlook MS Outlook [Prop] 3) Aethera. 1) Sylpheed. 2) Sylpheed-claws. Clientes de email al estilo The Bat 3) Kmail. The Bat 4) Gnus. 5) Balsa. 1) Pine. 2) Mutt. Cliente de email en Mutt for Windows [de], 3) Gnus. -

The Table of Equivalents / Replacements / Analogs of Windows Software in Linux

The table of equivalents / replacements / analogs of Windows software in Linux. Last update: 16.07.2003, 31.01.2005, 27.05.2005, 04.12.2006 You can always find the last version of this table on the official site: http://www.linuxrsp.ru/win-lin-soft/. This page on other languages: Russian, Italian, Spanish, French, German, Hungarian, Chinese. One of the biggest difficulties in migrating from Windows to Linux is the lack of knowledge about comparable software. Newbies usually search for Linux analogs of Windows software, and advanced Linux-users cannot answer their questions since they often don't know too much about Windows :). This list of Linux equivalents / replacements / analogs of Windows software is based on our own experience and on the information obtained from the visitors of this page (thanks!). This table is not static since new application names can be added to both left and the right sides. Also, the right column for a particular class of applications may not be filled immediately. In future, we plan to migrate this table to the PHP/MySQL engine, so visitors could add the program themselves, vote for analogs, add comments, etc. If you want to add a program to the table, send mail to winlintable[a]linuxrsp.ru with the name of the program, the OS, the description (the purpose of the program, etc), and a link to the official site of the program (if you know it). All comments, remarks, corrections, offers and bugreports are welcome - send them to winlintable[a]linuxrsp.ru. Notes: 1) By default all Linux programs in this table are free as in freedom.