The Record of the Association of the Bar of the City of New York

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Orpe=Civ= V=Kfdeq Italic Flybynightitalic.Ttf

Examples Rush Font Name Rush File Name Album Element Notes Working Man WorkingMan.ttf Rush Logo, Album/Song RUSH Working Man Titles Fly By Night, regular and FlyByNightregular.ttf. orpe=civ=_v=kfdeq italic FlyByNightitalic.ttf Caress Of Steel CaressOfSteel.ttf Rush Logo, Album Title Need to Photoshop to get the correct style RUSH CARESS OF STEEL Syrinx Syrinx.ttf Rush Logo, Album/Song RUSH 2112 Titles ALL THE WORLD'S A STAGE (core font: Arial/Helvetica) Cover text Arial or Helvetica are core fonts for both Windows and Mac Farewell To Kings FarewellToKings.ttf Rush Logo, Album/Song Rush A Farewell To Kings Titles Strangiato Strangiato.ttf Rush Logo Similar to illustrated "Rush" Rush Hemispheres Hemispheres.ttf Album Title Custom font by Dave Ward. Includes special character for "Rush". Hemispheres | RUSH THROUGH TIME RushThroughTime RushThroughTime.ttf Album Title RUSH Jacob's Ladder JacobsLadder.ttf Rush Logo Hybrid font PermanentWaves PermanentWaves.ttf Album Title permanent waves Moving Pictures MovingPictures.ttf Rush Logo, Album Title Same font used for Archives, Permanent Waves general text, RUSH MOVING PICTURES Moving Pictures and Different Stages Exit...Stage Left Bold ExitStageLeftBold.ttf Rush Logo RUSH Exit...Stage Left ExitStageLeft.ttf Album Title Exit...Stage Left SIGNALS (core font: Garamond) Album Title Garamond, a core font in Windows and Mac Grace Under Pressure GraceUnderPressure.ttf Rush Logo, Album Title, Upper Case character set only RUSH GRACE UNDER PRESSURE Song Titles RUSH Grand Designs GrandDesigns.ttf Rush Logo RUSH Grand Designs Lined GrandDesignsLined.ttf Alternate version Best used at 24pt or larger Power Windows PowerWindows.ttf Album Title, Song Titles POWER WINDOWS Hold Your Fire Black HoldYourFireBlack.ttf Rush Logo Need to Photoshop to get the correct style RUSH Hold Your Fire HoldYourFire.ttf Album Title, Song Titles HOLD YOUR FIRE A Show Of Hands AShowofHands.ttf Song Titles Same font as Power Windows. -

Foreword 5 Introduction 6 About This Book 8 the Making of Taking Center Stage 14 Drum Key 30

TAKING CENTER STAGE a lifetime of live performance NEIL PEART by Joe Bergamini © 2012 Hudson Music LLC International Copyright Secured. All Rights Reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher. www.hudsonmusic.com ConTenTsConTenTsConTenTs Foreword 5 Introduction 6 About This Book 8 The Making of Taking Center Stage 14 Drum Key 30 CHAPTER 1: 2112 and All the World’s a Stage Tours (1976-77) 33 Drum Setup 35 CHAPTER 2: A Farewell to Kings Tour (1977) 36 Drum Setup 39 CHAPTER 3: Hemispheres Tour (1978-79) 40 Drum Setup 42 ”The Trees” 43 Analysis 43 Drum Transcription 45 “La Villa Strangiato” 49 Analysis 49 Drum Transcription 51 CHAPTER 4: Permanent Waves Tour (1979-80) 58 Drum Setup 60 ”The Spirit of Radio” 61 Analysis 61 Drum Transcription 62 ”Free Will” 66 Analysis 66 Drum Transcription 68 ”Natural Science” 73 Analysis 73 Drum Transcription 75 CHAPTER 5: Moving Pictures Tour (1980-81) 81 Drum Setup 84 ”Tom Sawyer” 85 Analysis 85 Drum Transcription 87 ”YYZ” 91 Analysis 91 Drum Transcription 93 CHAPTER 6: Signals Tour (1982-83) 97 Drum Setup 101 ”Subdivisions” 102 Analysis 102 Drum Transcription 104 CHAPTER 7: Grace Under Pressure and Power Windows Tours (1984-86) 108 Drum Setup 113 ”Marathon” 114 Analysis 115 Drum Transcription 116 2 CHAPTER 8: Hold Your Fire Tour (1987-88) 122 Drum Setup 126 ”Time Stand Still” 128 Analysis 128 Drum Transcription 129 CHAPTER 9: Presto Tour (1990) 134 Drum Setup 136 ”Presto” 138 Analysis 138 Drum Transcription 140 CHAPTER -

Rush Counterparts Complete Album Sheet Music

Rush Counterparts Complete Album Sheet Music Download rush counterparts complete album sheet music pdf now available in our library. We give you 6 pages partial preview of rush counterparts complete album sheet music that you can try for free. This music notes has been read 3136 times and last read at 2021-09-21 22:16:48. In order to continue read the entire sheet music of rush counterparts complete album you need to signup, download music sheet notes in pdf format also available for offline reading. Instrument: Drum Set, Percussion Ensemble: Musical Ensemble Level: Advanced [ READ SHEET MUSIC ] Other Sheet Music Rush Fly By Night Complete Album Rush Fly By Night Complete Album sheet music has been read 2927 times. Rush fly by night complete album arrangement is for Advanced level. The music notes has 6 preview and last read at 2021-09-24 11:32:01. [ Read More ] Rush Hold Your Fire Complete Album Rush Hold Your Fire Complete Album sheet music has been read 4258 times. Rush hold your fire complete album arrangement is for Advanced level. The music notes has 6 preview and last read at 2021-09-25 01:20:58. [ Read More ] Rush Vapor Trails Complete Album Rush Vapor Trails Complete Album sheet music has been read 1651 times. Rush vapor trails complete album arrangement is for Advanced level. The music notes has 6 preview and last read at 2021-09-21 11:44:42. [ Read More ] Rush Snakes Arrows Complete Album Rush Snakes Arrows Complete Album sheet music has been read 1585 times. -

Rush We Hold on Sheet Music

Rush We Hold On Sheet Music Download rush we hold on sheet music pdf now available in our library. We give you 2 pages partial preview of rush we hold on sheet music that you can try for free. This music notes has been read 2828 times and last read at 2021-09-24 02:25:25. In order to continue read the entire sheet music of rush we hold on you need to signup, download music sheet notes in pdf format also available for offline reading. Instrument: Drum Set, Percussion Ensemble: Musical Ensemble Level: Advanced [ READ SHEET MUSIC ] Other Sheet Music Rush Hold Your Fire Complete Album Rush Hold Your Fire Complete Album sheet music has been read 4258 times. Rush hold your fire complete album arrangement is for Advanced level. The music notes has 6 preview and last read at 2021-09-25 01:20:58. [ Read More ] Hold Up Hold Up sheet music has been read 3917 times. Hold up arrangement is for Intermediate level. The music notes has 1 preview and last read at 2021-09-24 15:46:52. [ Read More ] Rush Rush sheet music has been read 5325 times. Rush arrangement is for Advanced level. The music notes has 2 preview and last read at 2021-09-23 10:09:24. [ Read More ] Rush Different Strings Rush Different Strings sheet music has been read 3818 times. Rush different strings arrangement is for Intermediate level. The music notes has 2 preview and last read at 2021-09-22 11:11:16. [ Read More ] Hold Me While You Wait Hold Me While You Wait sheet music has been read 20120 times. -

Textu(R)Al Undercoding and the Music of the Rock Band Rush: String Quartets, Death Metal, Trip-Hop, and Other Tributes Durrell Bowman

Textu(r)al Undercoding and the Music of the Rock Band Rush: String Quartets, Death Metal, Trip-Hop, and other Tributes Durrell Bowman Rush Pre-professional period (1968-69) Original members included: Alex Lifeson (b. 1953), John Rutsey (b. 1953) Other early member: Geddy Lee (b. 1953) Early professional period (1969-74: one single, one album) Lee, Lifeson, Rutsey; mainly original songs by 1971 (Led Zeppelin influence) Single: “Not Fade Away” (1973, cover version of original by Buddy Holly, 1957-58) Album: Rush (1974, recorded 1973), including “Working Man” (written in 1971) 1974 – 2004 period (28 albums; 22 U.S. gold, platinum, or multi-platinum, 142 songs) Geddy Lee’s virtuosic bass playing and countertenor (high, falsetto-related) singing Alex Lifeson’s precise-yet-tuneful guitar playing Neil Peart’s (b. 1952) elaborately constructed drumming and lyrics 1974-78 (after Rush, five more studio albums, one live album, one anthology) individualism & progressive (“art”) rock influences, with heavy metal & hard rock example: “2112” (title suite from 2112, 1976) examples: “Closer to the Heart,” “Xanadu,” “Cygnus X-1” (A Farewell to Kings, 1977) example: “The Trees” (from Hemispheres, 1978) 1980-89 (six studio albums, one live album) toning down the more extreme individualism and “prog” (progressive) features other influences (post-punk, jazz-rock, synth-rock, music technology) examples: Permanent Waves (1980, including “The Spirit of Radio,” “Freewill”) Moving Pictures (1981, incl. “Tom Sawyer,” “Red Barchetta,” “YYZ,” “Limelight”) Signals -

UDLS: Friday, Sept 23, 2011 Murray Patterson What You See

UDLS: Friday, Sept 23, 2011 Murray Patterson What you see... I typical 70's band (formed in 1968 actually) I solid, timeless rock band { one of their initial inspirations: Led Zeppelin (example: What You're Doing) I well-known songs include: Limelight, Tom Sawyer, (maybe 2112, Subdivisions) What you see... I typical 70's band (formed in 1968 actually) I solid, timeless rock band { one of their initial inspirations: Led Zeppelin (example: What You're Doing) I well-known songs include: Limelight, Tom Sawyer, (maybe 2112, Subdivisions) In Pop Culture I some pretty weird dudes: sort of nerdy, outcast I lyrics: Subdivisions, The Body Electric I tour with Kiss (interview with Gene Simmons) I not mainstream, but has a huge cult following: quoted as \the most successful cult band next to Kiss" I featured in: Family Guy, South Park, Futurama, an episode of Trailer Park Boys, and in the movie \I Love you Man" I great documentary on the band { Rush: Beyond the Lighted Stage Wikipedia Sez: Rush is a Canadian rock band formed in August 1968, in the Willowdale neighbourhood of Toronto, Ontario. The band is composed of bassist, keyboardist, and lead vocalist Geddy Lee, guitarist Alex Lifeson, and drummer and lyricist Neil Peart. The band and its membership went through a number of re-configurations between 1968 and 1974, achieving their current form when Peart replaced original drummer John Rutsey in July 1974, two weeks before the group's first United States tour. Since the release of the band's self-titled debut album in March 1974, Rush has become known for its musicianship, complex compositions, and eclectic lyrical motifs drawing heavily on science fiction, fantasy, and philosophy, as well as addressing humanitarian, social, emotional, and environmental concerns. -

RUSH ... Albums & Lyrics

Finding My Way – RUSH track 1 – 5:06 You’ve done me no right, but you’ve done me some wrong. Yeah, oh yeah! Left me lonely each night Ooh, said I, while I sing my sad song. I’m comin’ out to get you. Ooh, sit down. Look out! I’m comin’. I’m comin’ out to find you. Whoa, whoa. Ooh, yeah. Ooh yeah. Look out! I’m comin’. Findin’ my way! Whoa, yeah. I’ve been gone so long I’m runnin’, I’ve lost count of the years. findin’ my way back home. Well, I sang some sad songs, I’m comin’. oh yes, and cried some bad tears. Ooh, babe, I said I’m runnin’. Whoa, babe, I said I’m comin’ Look out! I’m comin’. to get you, mama. Whoa, whoa. Said I’m runnin’. Look out! I’m comin’. Whoa, yeah. Ooh, babe, I said I’m comin’ for you, babe. I’m runnin’, I said I’m runnin’. finding my way back home. Ooh yes, babe, I said I’m comin’ Oh yeah! to get you, babe. I said I’m comin’. Yeah, oh yeah! Ooh, yeah. Ooh, said I, I’m findin’, I’m comin’ back to look for you. I’m findin’ my way back home. Ooh, sit down. Well, I’ve had it for now, I’m goin’ by the back door. livin’ on the road. Ooh, yeah. Ooh yeah. Ooh, yeah. Findin’ my way! Ooh, yeah. Findin’ my way! I Need Some Love – RUSH track 2 – 2:19 I’m runnin’ here, I’m runnin’ there. -

Rush, Musicians' Rock, and the Progressive Post-Counterculture

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Permanent Change: Rush, Musicians’ Rock, and the Progressive Post-Counterculture A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Musicology by Durrell Scott Bowman 2003 © Copyright by Durrell Scott Bowman 2003 The dissertation of Durrell Scott Bowman is approved. ____________________________________ _ Susan McClary ____________________________________ Mitchell Morris ____________________________________ Christopher Waterman ____________________________________ Robert Walser, Committee Chair University of California, Los Angeles 2003 ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Figures and Tables (lists of) ......................................................................................... iv Musical Examples (lists of).............................................................................................v Acknowledgements ....................................................................................................... vi Vita ............................................................................................................................... viii Publications and Presentations.................................................................................... ix Abstract of the Dissertation ......................................................................................... xi Introduction ....................................................................................................................1 Chapter 1 Cast in This Unlikely -

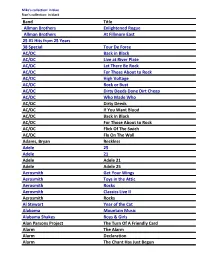

Band Title Allman Brothers Enlightened Rogue Allman

Mike's collection: in blue Stan's collection: in black Band Title Allman Brothers Enlightened Rogue Allman Brothers At Fillmore East 25 #1 Hits from 25 Years 38 Special Tour De Force AC/DC Back in Black AC/DC Live at River Plate AC/DC Let There Be Rock AC/DC For Those About to Rock AC/DC High Voltage AC/DC Rock or Bust AC/DC Dirty Deeds Done Dirt Cheap AC/DC Who Made Who AC/DC Dirty Deeds AC/DC If You Want Blood AC/DC Back In Black AC/DC For Those About to Rock AC/DC Flick Of The Swich AC/DC Fly On The Wall Adams, Bryan Reckless Adele 25 Adele 21 Adele Adele 21 Adele Adele 25 Aerosmith Get Your Wings Aerosmith Toys in the Attic Aerosmith Rocks Aerosmith Classics Live II Aerosmith Rocks Al Stewart Year of the Cat Alabama Mountain Music Alabama Shakes Boys & Girls Alan Parsons Project The Turn Of A Friendly Card Alarm The Alarm Alarm Declaration Alarm The Chant Has Just Begun Mike's collection: in blue Stan's collection: in black Alarm The Deceiver Alarm Absolute Reality Alarm Spirit Of 76 Alarm Strength Alarm Presence Of Love Alarm Change Aldean, Jason Old Boots New Dirt Aldo Nova Subject Alice in Chains Black Gives Way to Blue Alice In Chains Black Gives Way To Blue Alice In Chains The Devil Put Dinosaurs Here Allman Brothers Live at Beacon Theatre Allman Brothers Eat a Peach Allman Brothers Beginnings Allman Brothers Brothers and Sisters Allman Brothers The Allman Brothers Band Allman Brothers Live at Fillmore East Allman Brothers Duane Allman Anthology Allman Brothers Eat A Peach Allman Brothers Beginnings Allman Brothers The Greg Allman -

Chart-Chronology Singles and Albums

www.chart-history.net vdw56 PDF-files with all chart-entries plus covers on https://chart-history.net/chart-chronologie/ RUSH Chart-Chronology Singles and Albums 1976 Germany United Kingdom From the 1950ies U S A to the current charts compiled by Volker Dörken Chart - Chronology The Top-100 Singles and Albums from Germany, the United Kingdom and the USA Rush Rush was a Canadian rock band formed in Toronto in 1968, consisting of Geddy Lee (bass, vocals, keyboards, composer), Alex Lifeson (guitars, composer), and Neil Peart (drums, percussion, lyricist). After its formation in 1968, the band went through several configurations before arriving at its classic power trio lineup with the addition of Peart in 1974, who replaced original drummer John Rutsey right after the release of their self-titled debut album, which contained their first radio hit, "Working Man". This lineup had remained intact for the duration of the band's career. Singles 15 5 --- --- Longplay 31 25 13 --- B P Top 100 Top 40 Top 10 # 1 B P Top 100 Top 40 Top 10 # 1 xxx --- --- --- --- 11 17 6 --- --- 13 12 4 --- --- 3 24 17 8 --- 21 8 1 --- --- 2 30 24 12 --- Singles D G B U S A 1 Fly By Night/In The Mood 01/1977 88 2 Closer To The Heart 02/1978 36 11/1977 76 3 The Spirit Of Radio 03/1980 13 02/1980 51 4 Limelight 03/1981 55 5 Vital Signs / A Passage To Bangkok 03/1981 41 6 Tom Sawyer 10/1981 25 06/1981 44 7 Closer To The Heart [live] 12/1981 69 8 New World Man 09/1982 42 09/1982 21 ► # 1 - Hit in Canada 9 Subdivsions 10/1982 53 10 Countdown / New World Man 05/1983 36 11 The Body Electric 05/1984 56 12 The Big Money 10/1985 46 11/1985 45 13 Time Stand Still 10/1987 42 14 Prime Mover 04/1988 43 15 Roll The Bones 03/1992 49 Longplay D G B U S A 1 2112 05/1976 61 2 All The World's A Stage 10/1976 40 3 A Farewell To Kings 10/1977 22 09/1977 33 4 Hemispheres 11/1978 14 12/1978 47 5 Permanent Waves 06/2020 47 01/1980 3 02/1980 4 ►The album entered the German charts not before June 2020 6 Moving Pictures 02/1981 3 03/1981 3 ►# 1 - Album in Canada 7 Exit Stage Left .. -

Geddy Lee, Alex Lifeson Und Neil Peart Sind Seit 38 Lahren Das Rock-Trio Rush - Eine Band, Die Unter Musikern Hochste Anerkennung Genief3t

Geddy Lee, Alex Lifeson und Neil Peart sind seit 38 lahren das Rock-Trio Rush - eine Band, die unter Musikern hochste Anerkennung genief3t. Das Erfolgskonzept besteht aus komplexen Songstrukturen, einem unverwechselbaren Bombast-Sound und der Bereitschafi, sich stetig weiterzuentwickeln. 1m luni 2012 erscheint das zwanzigste Rush-Studioalbum. Wir sprachen mit Frontmann Geddy Lee. nwiefern unterscheidet sich euer neues Songs llnd einer besonderen Atmosphare. Es auf diese Weise von jedem StUck spontane Album Clockwork Angels von Alben wie erzahlt eine Geschichte und ist musikalisch Versionen entstanden, die sehr unterschiedlich I Snakes Et Arrows oder Vapor Trails? weniger berechenbar als einige seiner ausflelen. Nick oder "The Mighty Booujzhe", Geddy Lee: In vielerlei Hinsicht sind die Vorganger. wie wir ihn seitdem nennen, hat dann die Unterschiede zu den Vorgangeralben gar besten Takes ausgesucht. nicht so gravierend: Es ist seit 38 Jahren die Wurden die Songs im Studio live eingespielt? gleiche hyperaktive Rhythmusgruppe, die in Wahrend Ne il seine Parts eingespielt hat, saB Warum nennt ihr ihn "The Mighty Booujzhe"? regelmaJ3igen Abstanden Alben aufnimmt. ich im Kontrollraum des Studios und habe Weil er, um Neil zu erklaren, wie er sich einen [Lachtl Der Sound ist derselbe, typisch Rush: ihn am Bass begleitet. Normalerweise ist Neil Drum-Part vorsteLlt, die Schlagzeugsounds bombastisch und energiegeladen. Aber wir jemand, der sich vor den Aufnahmen extrem mit dem Mund nachmacht. "Booujzhe" ist der haben diesmal bei der Performance sehr gut vorbereitet. Er libt j eden einzelnen Drum Abschlag mit Crash-Becken und Bass-Drum. viel mehr Wert auf Spontaneitat gelegt. Break unzahlige Male und spielt ihn spater auf Die Songs sollen frisch und atmospharisch dem Album genau so. -

Rush Hold Your Fire Complete Album Sheet Music

Rush Hold Your Fire Complete Album Sheet Music Download rush hold your fire complete album sheet music pdf now available in our library. We give you 6 pages partial preview of rush hold your fire complete album sheet music that you can try for free. This music notes has been read 4302 times and last read at 2021-09-28 11:18:56. In order to continue read the entire sheet music of rush hold your fire complete album you need to signup, download music sheet notes in pdf format also available for offline reading. Instrument: Drum Set, Percussion Ensemble: Musical Ensemble Level: Advanced [ READ SHEET MUSIC ] Other Sheet Music Rush Counterparts Complete Album Rush Counterparts Complete Album sheet music has been read 3169 times. Rush counterparts complete album arrangement is for Advanced level. The music notes has 6 preview and last read at 2021-09-28 19:34:00. [ Read More ] Rush Fly By Night Complete Album Rush Fly By Night Complete Album sheet music has been read 2971 times. Rush fly by night complete album arrangement is for Advanced level. The music notes has 6 preview and last read at 2021-09-28 06:52:33. [ Read More ] Rush Vapor Trails Complete Album Rush Vapor Trails Complete Album sheet music has been read 1706 times. Rush vapor trails complete album arrangement is for Advanced level. The music notes has 6 preview and last read at 2021-09-28 13:55:51. [ Read More ] Rush Power Windows Complete Album Rush Power Windows Complete Album sheet music has been read 2124 times.