13 More Than They Bargained For

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Theme Park As "De Sprookjessprokkelaar," the Gatherer and Teller of Stories

University of Central Florida STARS Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 2018 Exploring a Three-Dimensional Narrative Medium: The Theme Park as "De Sprookjessprokkelaar," The Gatherer and Teller of Stories Carissa Baker University of Central Florida, [email protected] Part of the Rhetoric Commons, and the Tourism and Travel Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Doctoral Dissertation (Open Access) is brought to you for free and open access by STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STARS Citation Baker, Carissa, "Exploring a Three-Dimensional Narrative Medium: The Theme Park as "De Sprookjessprokkelaar," The Gatherer and Teller of Stories" (2018). Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019. 5795. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd/5795 EXPLORING A THREE-DIMENSIONAL NARRATIVE MEDIUM: THE THEME PARK AS “DE SPROOKJESSPROKKELAAR,” THE GATHERER AND TELLER OF STORIES by CARISSA ANN BAKER B.A. Chapman University, 2006 M.A. University of Central Florida, 2008 A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the College of Arts and Humanities at the University of Central Florida Orlando, FL Spring Term 2018 Major Professor: Rudy McDaniel © 2018 Carissa Ann Baker ii ABSTRACT This dissertation examines the pervasiveness of storytelling in theme parks and establishes the theme park as a distinct narrative medium. It traces the characteristics of theme park storytelling, how it has changed over time, and what makes the medium unique. -

Apr-May 1980

MODERN DRUMMER VOL. 4 NO. 2 FEATURES: NEIL PEART As one of rock's most popular drummers, Neil Peart of Rush seriously reflects on his art in this exclusive interview. With a refreshing, no-nonsense attitude. Peart speaks of the experi- ences that led him to Rush and how a respect formed between the band members that is rarely achieved. Peart also affirms his belief that music must not be compromised for financial gain, and has followed that path throughout his career. 12 PAUL MOTIAN Jazz modernist Paul Motian has had a varied career, from his days with the Bill Evans Trio to Arlo Guthrie. Motian asserts that to fully appreciate the art of drumming, one must study the great masters of the past and learn from them. 16 FRED BEGUN Another facet of drumming is explored in this interview with Fred Begun, timpanist with the National Symphony Orchestra of Washington, D.C. Begun discusses his approach to classical music and the influences of his mentor, Saul Goodman. 20 INSIDE REMO 24 RESULTS OF SLINGERLAND/LOUIE BELLSON CONTEST 28 COLUMNS: EDITOR'S OVERVIEW 3 TEACHERS FORUM READERS PLATFORM 4 Teaching Jazz Drumming by Charley Perry 42 ASK A PRO 6 IT'S QUESTIONABLE 8 THE CLUB SCENE The Art of Entertainment ROCK PERSPECTIVES by Rick Van Horn 48 Odd Rock by David Garibaldi 32 STRICTLY TECHNIQUE The Technically Proficient Player JAZZ DRUMMERS WORKSHOP Double Time Coordination by Paul Meyer 50 by Ed Soph 34 CONCEPTS ELECTRONIC INSIGHTS Drums and Drummers: An Impression Simple Percussion Modifications by Rich Baccaro 52 by David Ernst 38 DRUM MARKET 54 SHOW AND STUDIO INDUSTRY HAPPENINGS 70 A New Approach Towards Improving Your Reading by Danny Pucillo 40 JUST DRUMS 71 STAFF: EDITOR-IN-CHIEF: Ronald Spagnardi FEATURES EDITOR: Karen Larcombe ASSOCIATE EDITORS: Mark Hurley Paul Uldrich MANAGING EDITOR: Michael Cramer ART DIRECTOR: Tom Mandrake The feature section of this issue represents a wide spectrum of modern percussion with our three lead interview subjects: Rush's Neil Peart; PRODUCTION MANAGER: Roger Elliston jazz drummer Paul Motian and timpanist Fred Begun. -

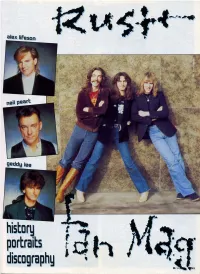

Rush Three of Them Decided to - Geddy Recieved a Phone Reform Rush but Without Call from Alex

history portraits J , • • • discography •M!.. ..45 I geddylee J bliss,s nth.slzers. vDcals neil pearl: percussion • alex liFesDn guitars. synt.hesizers plcs: Relay Photos Ltd (8); Mark Weiss (2); Tom Farrington (1): Georg Chin (1) called Gary Lee, generally the rhythm 'n' blues known as 'Geddy' be combo Ogilvie, who cause of his Polish/Jewish shortly afterwards also roots, and a bassist rarely changed their me to seen playing anything JUdd, splitting up in Sep other than a Yardbirds bass tember of the sa'l1le year. line. John and Alex, w. 0 were In September of the same in Hadrian, contacted year The Projection had Geddy again, and the renamed themselves Rush three of them decided to - Geddy recieved a phone reform Rush but without call from Alex. who was in Lindy Young, who had deep trouble. Jeff Jones started his niversity was nowhere to be found, course by then. In Autumn although a gig was 1969 the first Led Zeppelin planned for that evening. LP was released, and it hit Because the band badly Alex, Geddy an(i John like needed the money, Geddy a hammer. Rush shut them helped them out, not just selves away in their rehe providing his amp, but also arsal rooms, tUfned up the jumping in at short notice amp and discovered the to play bass and sing. He fascination of heavy was familiar with the Rush metaL. set alreadY, as they only The following months played well-known cover were going toJprove tough versions, and with his high for the three fYoung musi voice reminiscent of Ro cians who were either still bert Plant, he comple at school or at work. -

Geddy Lee DI-2112 Signature

POWER REQUIREMENTS •Utilizes two (2) standard 9V alkaline batteries (not included). NOTE: Input jack activates batteries. To conserve energy, unplug when not in use. Power Consumption: approx. 55mA. Geddy Lee Signature •USE DC POWER SUPPLY ONLY! Failure to do so may damage the unit and void warranty. DC Power Supply Specifications: SansAmp DI-2112 -18V DC regulated or unregulated, 100mA minimum; -2.1mm female plug, center negative (-). •Refer to “Power Considerations” in Noteworthy Notes on page 8. WARNINGS: • Attempting to repair unit is not recommended and may void warranty. • Missing or altered serial numbers automatically void warranty. For your own protection: be sure serial number labels on the unit’s back plate and exterior box are intact, and return your warranty registration card. ONE YEAR LIMITED WARRANTY. PROOF OF PURCHASE REQUIRED. Manufacturer warrants unit to be free from defects in materials and workmanship for one (1) year from date of purchase to the original pur - chaser and is not transferable. This warranty does not include damage resulting from accident, misuse, abuse, alteration, or incorrect current or voltage. If unit becomes defective within warranty period, Tech 21 will repair or replace it free of charge. After expiration, Tech 21 will repair defective unit for a fee. ALL REPAIRS for residents of U.S. and Canada: Call Tech 21 for Return Authorization Number . Manufacturer will not accept packages without prior authorization, pre-paid freight (UPS preferred) and proper insurance. FOR PERSONAL ASSISTANCE & SERVICE: Contact Tech 21 weekdays from 9:00 AM to 5:00 PM, EST. Hand-built in the U.S.A. -

Orpe=Civ= V=Kfdeq Italic Flybynightitalic.Ttf

Examples Rush Font Name Rush File Name Album Element Notes Working Man WorkingMan.ttf Rush Logo, Album/Song RUSH Working Man Titles Fly By Night, regular and FlyByNightregular.ttf. orpe=civ=_v=kfdeq italic FlyByNightitalic.ttf Caress Of Steel CaressOfSteel.ttf Rush Logo, Album Title Need to Photoshop to get the correct style RUSH CARESS OF STEEL Syrinx Syrinx.ttf Rush Logo, Album/Song RUSH 2112 Titles ALL THE WORLD'S A STAGE (core font: Arial/Helvetica) Cover text Arial or Helvetica are core fonts for both Windows and Mac Farewell To Kings FarewellToKings.ttf Rush Logo, Album/Song Rush A Farewell To Kings Titles Strangiato Strangiato.ttf Rush Logo Similar to illustrated "Rush" Rush Hemispheres Hemispheres.ttf Album Title Custom font by Dave Ward. Includes special character for "Rush". Hemispheres | RUSH THROUGH TIME RushThroughTime RushThroughTime.ttf Album Title RUSH Jacob's Ladder JacobsLadder.ttf Rush Logo Hybrid font PermanentWaves PermanentWaves.ttf Album Title permanent waves Moving Pictures MovingPictures.ttf Rush Logo, Album Title Same font used for Archives, Permanent Waves general text, RUSH MOVING PICTURES Moving Pictures and Different Stages Exit...Stage Left Bold ExitStageLeftBold.ttf Rush Logo RUSH Exit...Stage Left ExitStageLeft.ttf Album Title Exit...Stage Left SIGNALS (core font: Garamond) Album Title Garamond, a core font in Windows and Mac Grace Under Pressure GraceUnderPressure.ttf Rush Logo, Album Title, Upper Case character set only RUSH GRACE UNDER PRESSURE Song Titles RUSH Grand Designs GrandDesigns.ttf Rush Logo RUSH Grand Designs Lined GrandDesignsLined.ttf Alternate version Best used at 24pt or larger Power Windows PowerWindows.ttf Album Title, Song Titles POWER WINDOWS Hold Your Fire Black HoldYourFireBlack.ttf Rush Logo Need to Photoshop to get the correct style RUSH Hold Your Fire HoldYourFire.ttf Album Title, Song Titles HOLD YOUR FIRE A Show Of Hands AShowofHands.ttf Song Titles Same font as Power Windows. -

(Anesthesia) Pulling Teeth Metallica

(Anesthesia) Pulling Teeth Metallica (How Sweet It Is) To Be Loved By You Marvin Gaye (Legend of the) Brown Mountain Light Country Gentlemen (Marie's the Name Of) His Latest Flame Elvis Presley (Now and Then There's) A Fool Such As I Elvis Presley (You Drive ME) Crazy Britney Spears (You're My) Sould and Inspiration Righteous Brothers (You've Got) The Magic Touch Platters 1, 2 Step Ciara and Missy Elliott 1, 2, 3 Gloria Estefan 10,000 Angels Mindy McCreedy 100 Years Five for Fighting 100% Pure Love Crystal Waters 100% Pure Love (Club Mix) Crystal Waters 1‐2‐3 Len Barry 1234 Coolio 157 Riverside Avenue REO Speedwagon 16 Candles Crests 18 and Life Skid Row 1812 Overture Tchaikovsky 19 Paul Hardcastle 1979 Smashing Pumpkins 1985 Bowling for Soup 1999 Prince 19th Nervous Breakdown Rolling Stones 1B Yo‐Yo Ma 2 Become 1 Spice Girls 2 Minutes to Midnight Iron Maiden 2001 Melissa Etheridge 2001 Space Odyssey Vangelis 2012 (It Ain't the End) Jay Sean 21 Guns Green Day 2112 Rush 21st Century Breakdown Green Day 21st Century Digital Boy Bad Religion 21st Century Kid Jamie Cullum 21st Century Schizoid Man April Wine 22 Acacia Avenue Iron Maiden 24‐7 Kevon Edmonds 25 or 6 to 4 Chicago 26 Miles (Santa Catalina) Four Preps 29 Palms Robert Plant 30 Days in the Hole Humble Pie 33 Smashing Pumpkins 33 (acoustic) Smashing Pumpkins 3am Matchbox 20 3am Eternal The KLF 3x5 John Mayer 4 in the Morning Gwen Stefani 4 Minutes to Save the World Madonna w/ Justin Timberlake 4 Seasons of Loneliness Boyz II Men 40 Hour Week Alabama 409 Beach Boys 5 Shots of Whiskey -

The History of Rock Music: 1970-1975

The History of Rock Music: 1970-1975 History of Rock Music | 1955-66 | 1967-69 | 1970-75 | 1976-89 | The early 1990s | The late 1990s | The 2000s | Alpha index Musicians of 1955-66 | 1967-69 | 1970-76 | 1977-89 | 1990s in the US | 1990s outside the US | 2000s Back to the main Music page Inquire about purchasing the book (Copyright © 2009 Piero Scaruffi) Sound 1973-78 (These are excerpts from my book "A History of Rock and Dance Music") Borderline 1974-78 TM, ®, Copyright © 2005 Piero Scaruffi All rights reserved. In the second half of the 1970s, Brian Eno, Larry Fast, Mickey Hart, Stomu Yamashta and many other musicians blurred the lines between rock and avantgarde. Brian Eno (34), ex-keyboardist for Roxy Music, changed the course of rock music at least three times. The experiment of fusing pop and electronics on Taking Tiger Mountain By Strategy (sep 1974 - nov 1974) changed the very notion of what a "pop song" is. Eno took cheap melodies (the kind that are used at the music-hall, on television commercials, by nursery rhymes) and added a strong rhythmic base and counterpoint of synthesizer. The result was similar to the novelty numbers and the "bubblegum" music of the early 1960s, but it had the charisma of sheer post-modernist genius. Eno had invented meta-pop music: avantgarde music that employs elements of pop music. He continued the experiment on Another Green World (aug 1975 - sep 1975), but then changed its perspective on Before And After Science (? 1977 - dec 1977). Here Eno's catchy ditties acquired a sinister quality. -

Book > Deluxe Guitar TAB Collection Authentic

PK8C8FRUTC \ Deluxe Guitar TAB Collection Authentic Guitar TAB Authentic Guitar-Tab Editions / Book Deluxe Guitar TA B Collection A uth entic Guitar TA B A uth entic Guitar-Tab Editions By Staff Alfred Music. Paperback. Condition: New. 220 pages. Dimensions: 11.8in. x 8.9in. x 0.6in.This collection, covering 30 years in the career of the most successful and influential progressive rock band in history is a tribute to Rushs brilliant guitarist Alex Lifeson, one of the fathers of the progressive rock guitar genre. The book contains 22 prog-rock classics commencing in the mid-70s and concluding with chart success Snakes and Arrows, all in complete TAB. Titles: The Big Money Closer to the Heart Distant Early Warning Dreamline Far Cry Fly by Night Freewill Ghost of a Chance The Larger Bowl Limelight New World Man One Little Victory Red Barchetta Show Dont Tell The Spirit of Radio Subdivisions Test for Echo The Trees Tom Sawyer Vital Signs Working Man YYZ. This item ships from multiple locations. Your book may arrive from Roseburg,OR, La Vergne,TN. Perfect Paperback. READ ONLINE [ 1.16 MB ] Reviews Completely essential read through publication. It normally does not expense excessive. It is extremely diicult to leave it before concluding, once you begin to read the book. -- Morris Cruickshank Here is the best pdf i actually have go through till now. We have study and i also am certain that i am going to planning to go through once again once more in the future. You will not sense monotony at at any time of the time (that's what catalogs are for regarding in the event you question me). -

Psaudio Copper

Issue 116 JULY 27TH, 2020 “Baby, there’s only two more days till tomorrow.” That’s from the Gary Wilson song, “I Wanna Take You On A Sea Cruise.” Gary, an outsider music legend, expresses what many of us are feeling these days. How many conversations have you had lately with people who ask, “what day is it?” How many times have you had to check, regardless of how busy or bored you are? Right now, I can’t tell you what the date is without looking at my Doug the Pug calendar. (I am quite aware of that big “Copper 116” note scrawled in the July 27 box though.) My sense of time has shifted and I know I’m not alone. It’s part of the new reality and an aspect maybe few of us would have foreseen. Well, as my friend Ed likes to say, “things change with time.” Except for the fact that every moment is precious. In this issue: Larry Schenbeck finds comfort and adventure in his music collection. John Seetoo concludes his interview with John Grado of Grado Labs. WL Woodward tells us about Memphis guitar legend Travis Wammack. Tom Gibbs finds solid hits from Sophia Portanet, Margo Price, Gerald Clayton and Gillian Welch. Anne E. Johnson listens to a difficult instrument to play: the natural horn, and digs Wanda Jackson, the Queen of Rockabilly. Ken hits the road with progressive rock masters Nektar. Audio shows are on hold? Rudy Radelic prepares you for when they’ll come back. Roy Hall tells of four weddings and a funeral. -

Getting to the Heart of Cultural Safety in Unama'ki

Getting to the Heart of Cultural Safety in Unama’ki: Considering kesultulinej (Love) De-Ann Sheppard Cape Breton University Cite as: Sheppard, D. M. (2020). Getting to the Heart of Cultural Safety in Unama’ki: Considering kesultulinej (Love). Witness: The Canadian Journal of Critical Nursing Discourse, Vol 2 (1), 51-65 https://doi.org/ 10.25071/2291-5796.57 Abstract Reflecting upon my early knowledge landscapes, situated within the unceded Mi’kmaq territory of Unama’ki (Cape Breton, Nova Scotia), living the Peace & Friendship Treaty and the teachings of Mi’kmaw Elders, I contemplate the essential relationship with land and language, specifically, kesultulinej (love as action) and etuaptmumk (two-eyed seeing) to Cultural Safety. I recognize my position, privilege, and Responsibility in teaching and learning about the contextual meanings of Cultural Safety, situated in specific Indigenous terrains and in relation with the land, across time, and relationships. Critical reflection on my story and experiences challenge me to consider why and how Maori nursing theorizations of Cultural Safety have been indoctrinated into the language of national nursing education by the Canadian Association of Schools of Nursing (CASN), Canadian Nurses Association (CNA) and most provincial nursing regulatory bodies; this is increasingly relevant as nursing education is progressively shaped by neoliberal and Indigenizing agendas. As I contemplate wrapping Cultural Safety with kesultulinej, I see the potential to decolonize nursing. Mi’kmaw teachings of etuaptmumk and kesultulinej call forth Responsibilities to act, and in doing so move us into a space of potential to resist the colonizing forces within nursing. In this moment I realize the interconnected meaning of being amidst these relationships that matter to me as a person and as a nurse; relationships that are marked by love, care and compassion. -

GEDDY EASTON 'LEE Master of the ,Hook Bass + Power = Progressive Pop ERIC 'JOHNSON the Wat M Tone of a TEXAS TWISTER

- 802135 MAY 1986 $2.50 Inside This Issue: A SPECIAL Billy Idol's STEVE STEVENS (not -so-secret) CASSETTE Secret See Page 54 Weapon For Details THE CARS' RUSH'S ELLIOT GEDDY EASTON 'LEE Master Of The ,Hook Bass + Power = Progressive Pop ERIC 'JOHNSON The Wat m Tone Of A TEXAS TWISTER PLUS: Lonnie Mack Albert Collins Roy Buchanan , 'Tony MacAlpine o Curtis Mayfield MORE BASS, MORE SPACE IN THE MODERN WORLD Power Windows is the best Rush albutn in years because the band ----and the bass---- has returned to the roots of its sound ... tneticulously. BY JOHN SWENSON It has been a long, vertiginous and damn exciting roller coaster ride for Rush over the past decade-and-a-half. The group has gone from being unabashed Led Zeppelinites to kings of the concept album to the thinking man's heavy metal band to an uneasy combination of eighties record ing styles and seventies relentlessness. One thing Rush has never done is rest on its collective laurels-bassist Geddy Lee, guitarist Alex Lifeson and drummer Neil Peart have always been the first to point out the band's shortcomings when they feel legitimate deficiencies have surfaced. Accordingly, Lee was quick to admit his dissatisfaction with the band's last album, Grace Under Pressure , even though the record , which went platinum, has con solidated the band's position as one of Mercury/Polygram's most important acts. "We realized with Grace Under Pres sure ," said Lee on completion of the new album , Power Windows, "that we were not a techno-pop band. -

ATTENTION All Planets of the Solar Federationii'

i~~30 . .~,.~.* ~~~ Welcome to the latest issue of 'Spirit'. From this issue we are reverting to quarterly publication, hopefully next year we will go back to bi-monthly, once the band are active again. Please join me in welcoming Stewart Gilray aboard as assistant editor. Good luck to Neil Elliott with the Dream Theater fan zine he is currently producing, Neil's address can be found in the perman ant trades section if you are interested. Alex will be appearing at this years Kumbaya Festival in Toronto on the 2nd September, as .... with previous years this Aids benefit show will feature the cream of Canadian talent, Vol 8 No 1 giving their all for a good cause. Ray our North American corespondent will be attending Published quarterly by:- the show (lucky bastard) he will be fileing a full report (with pictures) for the next issue, won't you Ray? Mick Burnett, Alex should have his solo album (see interview 23, Garden Close, beginning page 3) in the shops by October. Chinbrook Road, If all goes well the album should be released Grove Park, in Europe at the same time as North America. London. Next issue of 'Spirit' should have an exclus S-E-12 9-T-G ive interview with Alex telling us all about England. the album. Editor: Mick Burnett The band should be getting back together to Asst Editor: Stewart Gilray begin work writing the new album in September. Typist: Janet Balmer Recording to commence Jan/Feb of next year Printers: C.J.L. with Peter Collins once more at the helm.