Rush, Musicians' Rock, and the Progressive Post-Counterculture

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PERFORMED IDENTITIES: HEAVY METAL MUSICIANS BETWEEN 1984 and 1991 Bradley C. Klypchak a Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate

PERFORMED IDENTITIES: HEAVY METAL MUSICIANS BETWEEN 1984 AND 1991 Bradley C. Klypchak A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2007 Committee: Dr. Jeffrey A. Brown, Advisor Dr. John Makay Graduate Faculty Representative Dr. Ron E. Shields Dr. Don McQuarie © 2007 Bradley C. Klypchak All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Dr. Jeffrey A. Brown, Advisor Between 1984 and 1991, heavy metal became one of the most publicly popular and commercially successful rock music subgenres. The focus of this dissertation is to explore the following research questions: How did the subculture of heavy metal music between 1984 and 1991 evolve and what meanings can be derived from this ongoing process? How did the contextual circumstances surrounding heavy metal music during this period impact the performative choices exhibited by artists, and from a position of retrospection, what lasting significance does this particular era of heavy metal merit today? A textual analysis of metal- related materials fostered the development of themes relating to the selective choices made and performances enacted by metal artists. These themes were then considered in terms of gender, sexuality, race, and age constructions as well as the ongoing negotiations of the metal artist within multiple performative realms. Occurring at the juncture of art and commerce, heavy metal music is a purposeful construction. Metal musicians made performative choices for serving particular aims, be it fame, wealth, or art. These same individuals worked within a greater system of influence. Metal bands were the contracted employees of record labels whose own corporate aims needed to be recognized. -

JAMES CUMMINS Bookseller Catalogue 121 James Cummins Bookseller Catalogue 121 to Place Your Order, Call, Write, E-Mail Or Fax

JAMES CUMMINS bookseller catalogue 121 james cummins bookseller catalogue 121 To place your order, call, write, e-mail or fax: james cummins bookseller 699 Madison Avenue, New York City, 10065 Telephone (212) 688-6441 Fax (212) 688-6192 e-mail: [email protected] jamescumminsbookseller.com hours: Monday – Friday 10:00 – 6:00, Saturday 10:00 – 5:00 Members A.B.A.A., I.L.A.B. front cover: item 20 inside front cover: item 12 inside rear cover: item 8 rear cover: item 19 catalogue photography by nicole neenan terms of payment: All items, as usual, are guaranteed as described and are returnable within 10 days for any reason. All books are shipped UPS (please provide a street address) unless otherwise requested. Overseas orders should specify a shipping preference. All postage is extra. New clients are requested to send remittance with orders. Libraries may apply for deferred billing. All New York and New Jersey residents must add the appropriate sales tax. We accept American Express, Master Card, and Visa. 1 ALBIN, Eleazar. A Natural History of English Insects Illustrated with a Hundred Copper Plates, Curiously Engraven from the Life: And (for those whose desire it) Exactly Coloured by the Author [With:] [Large Notes, and many Curious Observations. By W. Derham]. With 100 hand-colored engraved plates, each accompanied by a letterpress description. [2, title page dated 1720 (verso blank)], [2, dedica- tion by Albin], [4, preface], [4, list of subscribers], [2, title page dated 1724 (verso blank)], [2, dedication by Derham; To the Reader (on verso)], 26, [2, Index], [100] pp. -

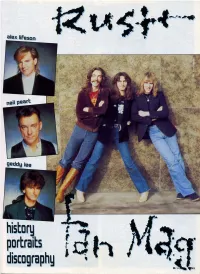

Rush Three of Them Decided to - Geddy Recieved a Phone Reform Rush but Without Call from Alex

history portraits J , • • • discography •M!.. ..45 I geddylee J bliss,s nth.slzers. vDcals neil pearl: percussion • alex liFesDn guitars. synt.hesizers plcs: Relay Photos Ltd (8); Mark Weiss (2); Tom Farrington (1): Georg Chin (1) called Gary Lee, generally the rhythm 'n' blues known as 'Geddy' be combo Ogilvie, who cause of his Polish/Jewish shortly afterwards also roots, and a bassist rarely changed their me to seen playing anything JUdd, splitting up in Sep other than a Yardbirds bass tember of the sa'l1le year. line. John and Alex, w. 0 were In September of the same in Hadrian, contacted year The Projection had Geddy again, and the renamed themselves Rush three of them decided to - Geddy recieved a phone reform Rush but without call from Alex. who was in Lindy Young, who had deep trouble. Jeff Jones started his niversity was nowhere to be found, course by then. In Autumn although a gig was 1969 the first Led Zeppelin planned for that evening. LP was released, and it hit Because the band badly Alex, Geddy an(i John like needed the money, Geddy a hammer. Rush shut them helped them out, not just selves away in their rehe providing his amp, but also arsal rooms, tUfned up the jumping in at short notice amp and discovered the to play bass and sing. He fascination of heavy was familiar with the Rush metaL. set alreadY, as they only The following months played well-known cover were going toJprove tough versions, and with his high for the three fYoung musi voice reminiscent of Ro cians who were either still bert Plant, he comple at school or at work. -

Adult Contemporary Radio at the End of the Twentieth Century

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Theses and Dissertations--Music Music 2019 Gender, Politics, Market Segmentation, and Taste: Adult Contemporary Radio at the End of the Twentieth Century Saesha Senger University of Kentucky, [email protected] Digital Object Identifier: https://doi.org/10.13023/etd.2020.011 Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Senger, Saesha, "Gender, Politics, Market Segmentation, and Taste: Adult Contemporary Radio at the End of the Twentieth Century" (2019). Theses and Dissertations--Music. 150. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/music_etds/150 This Doctoral Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Music at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations--Music by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STUDENT AGREEMENT: I represent that my thesis or dissertation and abstract are my original work. Proper attribution has been given to all outside sources. I understand that I am solely responsible for obtaining any needed copyright permissions. I have obtained needed written permission statement(s) from the owner(s) of each third-party copyrighted matter to be included in my work, allowing electronic distribution (if such use is not permitted by the fair use doctrine) which will be submitted to UKnowledge as Additional File. I hereby grant to The University of Kentucky and its agents the irrevocable, non-exclusive, and royalty-free license to archive and make accessible my work in whole or in part in all forms of media, now or hereafter known. -

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Rocking My Life Away Writing About Music and Other Matters by Anthony Decurtis Rock Critic Lectures on Music

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Rocking My Life Away Writing about Music and Other Matters by Anthony DeCurtis Rock critic lectures on music. 'Rolling Stone' editor Anthony DeCurtis visited Kelly Writers House, but got mixed reviews. By Rebecca Blatt The Daily Pennsylvanian February 22, 2002. Another acclaimed writer visited the Kelly Writers House this week. But this one was not there to discuss poetry or prose -- he was there for rock and roll. On Tuesday afternoon, music critic Anthony DeCurtis spoke to about 25 people in the front room of the Writers House. The crowd included Penn students, professors and local music lovers. DeCurtis is an editor of Rolling Stone magazine, host of an internet music show and the author of Rocking My Life Away: Writing About Music and Other Matters. He won a Grammy Award for his essay accompanying Eric Clapton's Crossroads box set and contributes to many other publications as well. DeCurtis appeared very prepared for the lecture. He took the podium armed with a pad of notes and a pitcher of water. However, some felt that DeCurtis's speech lacked focus. College sophomore Daniel Kaplan was so disappointed with DeCurtis that he left the event early. "He was a writer so pleased with himself and his accomplishments that he seemed to forget that speeches are supposed to be coherent," Kaplan said. Philadelphia resident Hop Wechsler, however, was a little bit more forgiving. "I guess I was expecting more about how he got where he is," Wechsler said. "But what I got was fun for what it was." English Department Chairman David Wallace introduced DeCurtis. -

Orpe=Civ= V=Kfdeq Italic Flybynightitalic.Ttf

Examples Rush Font Name Rush File Name Album Element Notes Working Man WorkingMan.ttf Rush Logo, Album/Song RUSH Working Man Titles Fly By Night, regular and FlyByNightregular.ttf. orpe=civ=_v=kfdeq italic FlyByNightitalic.ttf Caress Of Steel CaressOfSteel.ttf Rush Logo, Album Title Need to Photoshop to get the correct style RUSH CARESS OF STEEL Syrinx Syrinx.ttf Rush Logo, Album/Song RUSH 2112 Titles ALL THE WORLD'S A STAGE (core font: Arial/Helvetica) Cover text Arial or Helvetica are core fonts for both Windows and Mac Farewell To Kings FarewellToKings.ttf Rush Logo, Album/Song Rush A Farewell To Kings Titles Strangiato Strangiato.ttf Rush Logo Similar to illustrated "Rush" Rush Hemispheres Hemispheres.ttf Album Title Custom font by Dave Ward. Includes special character for "Rush". Hemispheres | RUSH THROUGH TIME RushThroughTime RushThroughTime.ttf Album Title RUSH Jacob's Ladder JacobsLadder.ttf Rush Logo Hybrid font PermanentWaves PermanentWaves.ttf Album Title permanent waves Moving Pictures MovingPictures.ttf Rush Logo, Album Title Same font used for Archives, Permanent Waves general text, RUSH MOVING PICTURES Moving Pictures and Different Stages Exit...Stage Left Bold ExitStageLeftBold.ttf Rush Logo RUSH Exit...Stage Left ExitStageLeft.ttf Album Title Exit...Stage Left SIGNALS (core font: Garamond) Album Title Garamond, a core font in Windows and Mac Grace Under Pressure GraceUnderPressure.ttf Rush Logo, Album Title, Upper Case character set only RUSH GRACE UNDER PRESSURE Song Titles RUSH Grand Designs GrandDesigns.ttf Rush Logo RUSH Grand Designs Lined GrandDesignsLined.ttf Alternate version Best used at 24pt or larger Power Windows PowerWindows.ttf Album Title, Song Titles POWER WINDOWS Hold Your Fire Black HoldYourFireBlack.ttf Rush Logo Need to Photoshop to get the correct style RUSH Hold Your Fire HoldYourFire.ttf Album Title, Song Titles HOLD YOUR FIRE A Show Of Hands AShowofHands.ttf Song Titles Same font as Power Windows. -

Bob Dylan Performs “It's Alright, Ma (I'm Only Bleeding),” 1964–2009

Volume 19, Number 4, December 2013 Copyright © 2013 Society for Music Theory A Foreign Sound to Your Ear: Bob Dylan Performs “It’s Alright, Ma (I’m Only Bleeding),” 1964–2009 * Steven Rings NOTE: The examples for the (text-only) PDF version of this item are available online at: http://www.mtosmt.org/issues/mto.13.19.4/mto.13.19.4.rings.php KEYWORDS: Bob Dylan, performance, analysis, genre, improvisation, voice, schema, code ABSTRACT: This article presents a “longitudinal” study of Bob Dylan’s performances of the song “It’s Alright, Ma (I’m Only Bleeding)” over a 45-year period, from 1964 until 2009. The song makes for a vivid case study in Dylanesque reinvention: over nearly 800 performances, Dylan has played it solo and with a band (acoustic and electric); in five different keys; in diverse meters and tempos; and in arrangements that index a dizzying array of genres (folk, blues, country, rockabilly, soul, arena rock, etc.). This is to say nothing of the countless performative inflections in each evening’s rendering, especially in Dylan’s singing, which varies widely as regards phrasing, rhythm, pitch, articulation, and timbre. How can music theorists engage analytically with such a moving target, and what insights into Dylan’s music and its meanings might such a study reveal? The present article proposes one set of answers to these questions. First, by deploying a range of analytical techniques—from spectrographic analysis to schema theory—it demonstrates that the analytical challenges raised by Dylan’s performances are not as insurmountable as they might at first appear, especially when approached with a strategic and flexible methodological pluralism. -

Dec. 22, 2015 Snd. Tech. Album Arch

SOUND TECHNIQUES RECORDING ARCHIVE (Albums recorded and mixed complete as well as partial mixes and overdubs where noted) Affinity-Affinity S=Trident Studio SOHO, London. (TRACKED AND MIXED: SOUND TECHNIQUES A-RANGE) R=1970 (Vertigo) E=Frank Owen, Robin Geoffrey Cable P=John Anthony SOURCE=Ken Scott, Discogs, Original Album Liner Notes Albion Country Band-Battle of The Field S=Sound Techniques Studio Chelsea, London. (TRACKED AND MIXED: SOUND TECHNIQUES A-RANGE) S=Island Studio, St. Peter’s Square, London (PARTIAL TRACKING) R=1973 (Carthage) E=John Wood P=John Wood SOURCE: Original Album liner notes/Discogs Albion Dance Band-The Prospect Before Us S=Sound Techniques Studio Chelsea, London. (PARTIALLY TRACKED. MIXED: SOUND TECHNIQUES A-RANGE) S=Olympic Studio #1 Studio, Barnes, London (PARTIAL TRACKING) R=Mar.1976 Rel. (Harvest) @ Sound Techniques, Olympic: Tracks 2,5,8,9 and 14 E= Victor Gamm !1 SOUND TECHNIQUES RECORDING ARCHIVE (Albums recorded and mixed complete as well as partial mixes and overdubs where noted) P=Ashley Hutchings and Simon Nicol SOURCE: Original Album liner notes/Discogs Alice Cooper-Muscle of Love S=Sunset Sound Recorders Hollywood, CA. Studio #2. (TRACKED: SOUND TECHNIQUES A-RANGE) S=Record Plant, NYC, A&R Studio NY (OVERDUBS AND MIX) R=1973 (Warner Bros) E=Jack Douglas P=Jack Douglas and Jack Richardson SOURCE: Original Album liner notes, Discogs Alquin-The Mountain Queen S= De Lane Lea Studio Wembley, London (TRACKED AND MIXED: SOUND TECHNIQUES A-RANGE) R= 1973 (Polydor) E= Dick Plant P= Derek Lawrence SOURCE: Original Album Liner Notes, Discogs Al Stewart-Zero She Flies S=Sound Techniques Studio Chelsea, London. -

Focus Group 7/26/10 1 FOCUS GROUP for the CITY of NEW BERLIN CITY CENTER JULY 26, 2010 Ted Wysocki, Alderman District 2 Welcome

Focus Group 7/26/10 FOCUS GROUP FOR THE CITY OF NEW BERLIN CITY CENTER JULY 26, 2010 Ted Wysocki, Alderman District 2 welcomed everyone to the Focus Group gathering. Carolyn Esswein and Mark Smith, GRAEF gave a power point presentation which can be found on the City’s website www.newberlin.org . Ms. Esswein asked for questions or comments: Ms. Esswein - How many use the library once a month? A show of hands indicated a few people did. Ms. Esswein - Do you use any of the other businesses in the area? A show of hands indicated a few people did. Ms. Esswein - Are you using services located throughout the entire City Center like where the new Sendik’s is going in, where the Walmart is? Focus Group Comment - Pick ‘n Save, Super Cuts, Subway, Dry Cleaner, Chinese Restaurant, Chumley’s Pub, Print Shop, Bank, Walmart, Hirschloffs, Great Wraps, Vision Cener, Dentist were places mentioned as places or services used in City Center. Sit down, white tablecloth restaurants where someone could entertain a client was indicated as something desired in City Center. Parking and Traffic Ms. Esswein - What is it you like about the area around the library? Is it easy to park when you go to Walmart or Pick ‘n Save? Focus Group Comment – Yes, it is very easy to park. Ms. Esswein – Is it easy to park in the area by Sendik’s? Focus Group Comment – Yes, it is easy to park. Ms. Esswein – Is it easy to park in the area by Great Wraps? Focus Group Comment – No. -

Global Environmental Policy with a Case Study of Brazil

ENVS 360 Global Environmental Policy with a Case Study of Brazil Professor Pete Lavigne, Environmental Studies and Director of the Colorado Water Workshop Taylor Hall 312c Office Hours T–Friday 11:00–Noon or by appointment 970-943-3162 – Mobile 503-781-9785 Course Policies and Syllabus ENVS 360 Global Environmental Policy. This multi-media and discussion seminar critically examines key perspectives, economic and political processes, policy actors, and institutions involved in global environmental issues. Students analyze ecological, cultural, and social dimensions of international environmental concerns and governance as they have emerged in response to increased recognition of global environmental threats, globalization, and international contributions to understanding of these issues. The focus of the course is for students to engage and evaluate texts within the broad policy discourse of globalization, justice and the environment. Threats to Earth's environment have increasingly become globalized and in response to at least ten major global threats—including global warming, deforestation, population growth and persistent organic pollutants—countries, NGOs and corporations have signed hundreds of treaties, conventions and various other types of agreements designed to protect or at least mitigate and minimize damage to the environment. The course provides an overview of developments and patterns in the epistemological, political, social and economic dimensions of global environmental governance as they have emerged over the past three decades. We will also undertake a case study of the interactions of Brazilian environmental policy central to several global environmental threats, including global warming and climate change, land degradation, and freshwater pollution and scarcity. The case study will analyze the intersections of major local, national and international environmental policies. -

Yes Highlights the Very Best of Yes Mp3, Flac, Wma

Yes Highlights The Very Best Of Yes mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Rock Album: Highlights The Very Best Of Yes Country: Australia Released: 1993 Style: Pop Rock, Prog Rock MP3 version RAR size: 1373 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1419 mb WMA version RAR size: 1575 mb Rating: 4.8 Votes: 675 Other Formats: ASF FLAC AHX AC3 AU ADX WAV Tracklist Hide Credits Survival Engineer – Gerald ChevinPerformer – Bill Bruford, Chris Squire, Jon 1 6:18 Anderson, Peter Banks, Tony KayeProducer – Paul Clay, YesWritten- By – Anderson* Time And A Word Arranged By [Orchestral Arrangements] – Tony CoxEngineer – Eddie 2 Offord*Performer – Bill Bruford, Chris Squire, Jon Anderson, Peter 4:31 Banks, Tony KayeProducer – Tony ColtonWritten-By – Foster*, Anderson* Starship Trooper Engineer – Eddie Offord*Performer – Bill Bruford, Chris Squire, (9:26) Jon Anderson, Steve Howe, Tony KayeProducer – Eddie Offord*, Yes Life Seeker 3a. Written-By – Anderson* Disillusion 3b. Written-By – Squire* Würm 3c. Written-By – Howe* I've Seen All Good People Engineer – Eddie Offord*Performer – Bill Bruford, Chris Squire, (6:53) Jon Anderson, Steve Howe, Tony KayeProducer – Eddie Offord*, Yes Your Move 4a. Written-By – Anderson* All Good People 4b. Written-By – Squire* Roundabout Engineer – Eddie Offord*Performer – Bill Bruford, Chris Squire, Jon 5 8:31 Anderson, Rick Wakeman, Steve HoweProducer – Eddie Offord*, YesWritten-By – Anderson*, Howe* Long Distance Runaround Engineer – Eddie Offord*Performer – Bill Bruford, Chris Squire, Jon 6 3:33 Anderson, Rick Wakeman, Steve -

ATTENTION All Planets of the Solar Federationii'

i~~30 . .~,.~.* ~~~ Welcome to the latest issue of 'Spirit'. From this issue we are reverting to quarterly publication, hopefully next year we will go back to bi-monthly, once the band are active again. Please join me in welcoming Stewart Gilray aboard as assistant editor. Good luck to Neil Elliott with the Dream Theater fan zine he is currently producing, Neil's address can be found in the perman ant trades section if you are interested. Alex will be appearing at this years Kumbaya Festival in Toronto on the 2nd September, as .... with previous years this Aids benefit show will feature the cream of Canadian talent, Vol 8 No 1 giving their all for a good cause. Ray our North American corespondent will be attending Published quarterly by:- the show (lucky bastard) he will be fileing a full report (with pictures) for the next issue, won't you Ray? Mick Burnett, Alex should have his solo album (see interview 23, Garden Close, beginning page 3) in the shops by October. Chinbrook Road, If all goes well the album should be released Grove Park, in Europe at the same time as North America. London. Next issue of 'Spirit' should have an exclus S-E-12 9-T-G ive interview with Alex telling us all about England. the album. Editor: Mick Burnett The band should be getting back together to Asst Editor: Stewart Gilray begin work writing the new album in September. Typist: Janet Balmer Recording to commence Jan/Feb of next year Printers: C.J.L. with Peter Collins once more at the helm.