Social Formation and Cultural Patterns of the Medieval World

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NAEVIUS After Livius Andronicus, Naevius1 Was the Second

CHAPTER THREE NAEVIUS Dispositio. The Clash of Myth and History Double Identity: Campanian and Roman After Livius Andronicus, Naevius1 was the second Latin epic poet. He was of "Campanian" origin (Gellius 1. 20. 14), which, according to Latin usage, means that he was from Capua,2 a city allegedly founded by Romulus, and his thoughts and feelings were those of a Roman, not without a large admixture of Campanian pride. Capua in his day was almost as important economically as Rome and Carthage and its citizens were fully aware of this (though it was not until the Second Punic War that it abandoned Rome). Naevius himself tells us (Varro apud Gell. 17. 21. 45) that he actively participated in the First Punic War. The experience of that great historical conflict led to the birth of the Bellum Poenicum, the first Roman national epic. Similarly, Ennius would write his Annales after the Second Punic War and Virgil his Aeneid after the Civil Wars. In 235 B.C., only five years after the first performance of a Latin play by Livius Andronicus, Naevius staged a drama of his own. Soon he became the greatest comic playwright, unsurpassed until Plautus. He did not restrain his sharp tongue even when speaking of the noblest families. Although he did not mention anyone by name, he unequivocally alluded to a rather unheroic moment in the life of the young Scipio (Com. 108-110 R), and his quarrel with the Metelli (ps. Ascon., Ad Cic. Verr. 1. 29), formerly dismissed as fiction,3 is accepted today as having some basis in fact. -

Roman Literature from Its Earliest Period to the Augustan Age

The Project Gutenberg EBook of History of Roman Literature from its Earliest Period to the Augustan Age. Volume I by John Dunlop This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at http://www.gutenberg.org/license Title: History of Roman Literature from its Earliest Period to the Augustan Age. Volume I Author: John Dunlop Release Date: April 1, 2011 [Ebook 35750] Language: English ***START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK HISTORY OF ROMAN LITERATURE FROM ITS EARLIEST PERIOD TO THE AUGUSTAN AGE. VOLUME I*** HISTORY OF ROMAN LITERATURE, FROM ITS EARLIEST PERIOD TO THE AUGUSTAN AGE. IN TWO VOLUMES. BY John Dunlop, AUTHOR OF THE HISTORY OF FICTION. ivHistory of Roman Literature from its Earliest Period to the Augustan Age. Volume I FROM THE LAST LONDON EDITION. VOL. I. PUBLISHED BY E. LITTELL, CHESTNUT STREET, PHILADELPHIA. G. & C. CARVILL, BROADWAY, NEW YORK. 1827 James Kay, Jun. Printer, S. E. Corner of Race & Sixth Streets, Philadelphia. Contents. Preface . ix Etruria . 11 Livius Andronicus . 49 Cneius Nævius . 55 Ennius . 63 Plautus . 108 Cæcilius . 202 Afranius . 204 Luscius Lavinius . 206 Trabea . 209 Terence . 211 Pacuvius . 256 Attius . 262 Satire . 286 Lucilius . 294 Titus Lucretius Carus . 311 Caius Valerius Catullus . 340 Valerius Ædituus . 411 Laberius . 418 Publius Syrus . 423 Index . 453 Transcriber's note . 457 [iii] PREFACE. There are few subjects on which a greater number of laborious volumes have been compiled, than the History and Antiquities of ROME. -

TRADITIONAL POETRY and the ANNALES of QUINTUS ENNIUS John Francis Fisher A

REINVENTING EPIC: TRADITIONAL POETRY AND THE ANNALES OF QUINTUS ENNIUS John Francis Fisher A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE FACULTY OF PRINCETON UNIVERSITY IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY RECOMMENDED FOR ACCEPTANCE BY THE DEPARTMENT OF CLASSICS SEPTEMBER 2006 UMI Number: 3223832 UMI Microform 3223832 Copyright 2006 by ProQuest Information and Learning Company. All rights reserved. This microform edition is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest Information and Learning Company 300 North Zeeb Road P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, MI 48106-1346 © Copyright by John Francis Fisher, 2006. All rights reserved. ii Reinventing Epic: Traditional Poetry and the Annales of Quintus Ennius John Francis Fisher Abstract The present scholarship views the Annales of Quintus Ennius as a hybrid of the Latin Saturnian and Greek hexameter traditions. This configuration overlooks the influence of a larger and older tradition of Italic verbal art which manifests itself in documents such as the prayers preserved in Cato’s De agricultura in Latin, the Iguvine Tables in Umbrian, and documents in other Italic languages including Oscan and South Picene. These documents are marked by three salient features: alliterative doubling figures, figurae etymologicae, and a pool of traditional phraseology which may be traced back to Proto-Italic, the reconstructed ancestor of the Italic languages. A close examination of the fragments of the Annales reveals that all three of these markers of Italic verbal art are integral parts of the diction the poem. Ennius famously remarked that he possessed three hearts, one Latin, one Greek and one Oscan, which the second century writer Aulus Gellius understands as ability to speak three languages. -

The Maltese Islands and the Sea in Antiquity

THE MALTESE ISLANDS AND THE SEA IN ANTIQUITY The Maltese Islands and the Sea in Antiquity TIMMY GAMBIN The events of history often lead to the islands… F. Braudel THE STRETCHES OF SEA EXTANT BETWEEN ISLANDS AND mainland may be observed as having primary-dual functionalities: that of ‘isolating’ islands and that of providing connectivity with land masses that lay beyond the islands’ shores. On smaller islands especially, access to the sea provided a gateway from which people, goods and ideas could flow. This chapter explores how, via their surrounding seas, events of history often led to the islands of Malta and Gozo. The timeframe covered consists of over one thousand years (circa 700 BC to circa 400 AD); a fluid period that saw the island move in and out of the political, military and economic orbits of various powers that dominated the Mediterranean during these centuries. Another notion of duality can be observed in the interaction that plays out between those coming from the outside and those inhabiting the islands. It would be mistaken to analyze Maltese history solely in the context of great powers that touched upon and ‘colonized’ the islands. This historical narrative will also cover important aspects such as how the islands were perceived from those approaching from out at sea: were the islands a hazard, a haven or possibly both at one and the same time? It is also essential to look at how the sea was perceived by the islanders: did the sea bring welcome commercial activity to the islands shores; did it carry 1 THE MALTESE ISLANDS AND THE SEA pirate vessels and enemy ships? As important as these questions are, this narrative would be incomplete without reference to how the sea helped shape and mould the way in which the people living on Malta and Gozo chose (or were forced) to live. -

A Stranger in a Strange Land: Medea in Roman Republican Tragedy1 Robert Cowan

CHAPTER 3 A Stranger in a Strange Land: Medea in Roman Republican Tragedy1 Robert Cowan The first performance of a Roman version of a Greek tragedy in 240 BC was a momentous event. It was not the beginning of Roman appropriation of Greek culture- Rome had had contact and complex interaction with Greek communities in Magna Graecia and elsewhere from earliest times - but it was an important landmark in the relationship between Greece and Rome. 2 When a tragedy by Livius Andronicus was performed to celebrate victory over Carthage in the First Punic War, a central cultural practice of an alien culture was adopted, adapted, appropriated and transformed to serve as a central cultural practice of Rome. It is significant that the first tragedy celebrated a victory (albeit over Carthage), since the appropriation of Greek tragedy was an act of cultural conquest, as Roman actors marched into and occupied the stage of Attic drama. Yet the event was more complex than that description suggests. In Horace's phrase, captured Greece captured its savage master.3 The writing ofRoman tragedy in the Greek style was simultaneously an act of self-confident literary invasion and of cultural submission to the thrall of a more established theatrical tradition. In terms of literary history, this complex interrelationship marks the beginning of Latin literature, in conjunction with Livius's Latin, Saturnian version of the Odyssey. In terms of culture, the flourishing of Roman drama coincided with the massive expansion of Roman territory and the accompanying challenge to its sense of identity. Dramas were performed at public festivals, /rrdi scaenici, organized by state officials, the aediles, and sponsored by influential elites. -

Introduction: Medea in Greece and Rome

INTRODUCTION: MEDEA IN GREECE AND ROME A J. Boyle maiusque mari Medea malum. Seneca Medea 362 And Medea, evil greater than the sea. Few mythic narratives of the ancient world are more famous than the story of the Colchian princess/sorceress who betrayed her father and family for love of a foreign adventurer and who, when abandoned for another woman, killed in revenge both her rival and her children. Many critics have observed the com plexities and contradictions of the Medea figure—naive princess, knowing witch, faithless and devoted daughter, frightened exile, marginalised alien, dis placed traitor to family and state, helper-màiden, abandoned wife, vengeful lover, caring and filicidal mother, loving and fratricidal sister, oriental 'other', barbarian saviour of Greece, rejuvenator of the bodies of animals and men, killer of kings and princesses, destroyer and restorer of kingdoms, poisonous stepmother, paradigm of beauty and horror, demi-goddess, subhuman monster, priestess of Hecate and granddaughter of the sun, bride of dead Achilles and ancestor of the Medes, rider of a serpent-drawn chariot in the sky—complex ities reflected in her story's fragmented and fragmenting history. That history has been much examined, but, though there are distinguished recent exceptions, comparatively little attention has been devoted to the specifically 'Roman' Medea—the Medea of the Republican tragedians, of Cicero, Varro Atacinus, Ovid, the younger Seneca, Valerius Flaccus, Hosidius Geta and Dracontius, and, beyond the literary field, the Medea of Roman painting and Roman sculp ture. Hence the present volume of Ramus, which aims to draw attention to the complex and fascinating use and abuse of this transcultural heroine in the Ro man intellectual and visual world. -

Download Horace: the SATIRES, EPISTLES and ARS POETICA

+RUDFH 4XLQWXV+RUDWLXV)ODFFXV 7KH6DWLUHV(SLVWOHVDQG$UV3RHWLFD Translated by A. S. Kline ã2005 All Rights Reserved This work may be freely reproduced, stored, and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non- commercial purpose. &RQWHQWV Satires: Book I Satire I - On Discontent............................11 BkISatI:1-22 Everyone is discontented with their lot .......11 BkISatI:23-60 All work to make themselves rich, but why? ..........................................................................................12 BkISatI:61-91 The miseries of the wealthy.......................13 BkISatI:92-121 Set a limit to your desire for riches..........14 Satires: Book I Satire II – On Extremism .........................16 BkISatII:1-22 When it comes to money men practise extremes............................................................................16 BkISatII:23-46 And in sexual matters some prefer adultery ..........................................................................................17 BkISatII:47-63 While others avoid wives like the plague.17 BkISatII:64-85 The sin’s the same, but wives are more trouble...............................................................................18 BkISatII:86-110 Wives present endless obstacles.............19 BkISatII:111-134 No married women for me!..................20 Satires: Book I Satire III – On Tolerance..........................22 BkISatIII:1-24 Tigellius the Singer’s faults......................22 BkISatIII:25-54 Where is our tolerance though? ..............23 BkISatIII:55-75 -

View of the Great

This dissertation has been 62—769 microfilmed exactly as received GABEL, John Butler, 1931- THE TUDOR TRANSLATIONS OF CICERO'S DE OFFICIIS. The Ohio State University, Ph.D., 1961 Language and Literature, modern University Microfilms, Inc., Ann Arbor, Michigan THE TUDOR TRANSLATIONS OP CICERO'S DE OFFICIIS DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of the Ohio State University By John Butler Gabel, B. A., M. A., A. M. ****** The Ohio State University 1961 Approved by Adviser Department of Ehglis7 PREFACE The purpose of this dissertation is to throw light on the sixteenth-century English translations of De Offioiis, one of Cicero’s most popular and most influential works. The dissertation first surveys the history and reputation of the Latin treatise to I600 and sketchs the lives of the English translators. It then establishes the facts of publication of the translations and identifies the Latin texts used in them. Finally it analyzes the translations themselves— their syntax, diction, and English prose style in general— against the background of the theory and prac tice of translation in their respective periods. I have examined copies of the numerous editions of the translations in the Folger Shakespeare Library, the Library of Congress, and the libraries of the Ohio State University and the University of Illinois. I have also made use of films of copies in the British Museum and the Huntington Library. I have indicated the location of the particular copies upon which the bibliographical descrip tions in Chapter 3 are based. -

Curriculum Vitae of Ruth Rothaus Caston March 2016 Dept. Of

Curriculum Vitae of Ruth Rothaus Caston March 2016 Dept. of Classical Studies 2160 Angell Hall, 435 S. State St. 1117 Lincoln Ave University of Michigan Ann Arbor, MI 48104 Ann Arbor, MI 48109 (734) 369-2699 (734) 764-1332 e-mail: [email protected] Employment University of Michigan, Dept. of Classical Studies, Associate Professor 2014- University of Michigan, Dept. of Classical Studies, Assistant Professor, 2008-2014 University of Michigan, Dept. of Classical Studies, Lecturer & Research Investigator, 2005-2008. University of California at Davis, Classics Program, Assistant Professor, 2000–2005. Education Brown University, 1995–2000; Ph.D. in Classics, 2000. The University of Texas at Austin, 1988–91; M.A. in Classics, 1990. Cornell University, 1984–88; B.A. in Classics, 1988. Academic Exchanges: 1994–95: DAAD Annual Grant Recipient, Universität Heidelberg. 1991–94: Visiting Scholar at Brown University. Summer 1989: Internationaler Ferienkurs, Universität Heidelberg. Spring 1987: The Intercollegiate Center for Classical Studies in Rome. Fall 1986: Classes at the Sorbonne, École des Sciences Politiques, Paris. Honors and Awards Michigan Humanities Award 2015-16. University Musical Society Mellon Faculty Fellow 2014-16. Life Member, Clare Hall, Elected Fall 2013. Visiting Fellow, Clare Hall, Cambridge, 2012-13. Loeb Classical Library Foundation Grant, 2003-4. Faculty Research Grants (UC Davis), 2000-1, 2003-4, 2004-5. University Fellowship (Brown University), Spring 1998, Fall 1998, Spring 1999. DAAD Annual Grant, Universität Heidelberg, 1994–95. Areas of Specialization Augustan poetry, Roman comedy, Roman satire, Ancient theories of the passions. Areas of Competence Greek & Roman rhetoric, the family in antiquity. Languages: Ancient Greek, Latin, French, German, Italian. -

Reading Death in Ancient Rome

Reading Death in Ancient Rome Reading Death in Ancient Rome Mario Erasmo The Ohio State University Press • Columbus Copyright © 2008 by The Ohio State University. All rights reserved. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Erasmo, Mario. Reading death in ancient Rome / Mario Erasmo. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN-13: 978-0-8142-1092-5 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN-10: 0-8142-1092-9 (cloth : alk. paper) 1. Death in literature. 2. Funeral rites and ceremonies—Rome. 3. Mourning cus- toms—Rome. 4. Latin literature—History and criticism. I. Title. PA6029.D43E73 2008 870.9'3548—dc22 2008002873 This book is available in the following editions: Cloth (ISBN 978-0-8142-1092-5) CD-ROM (978-0-8142-9172-6) Cover design by DesignSmith Type set in Adobe Garamond Pro by Juliet Williams Printed by Thomson-Shore, Inc. The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials. ANSI 39.48-1992. 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Contents List of Figures vii Preface and Acknowledgments ix INTRODUCTION Reading Death CHAPTER 1 Playing Dead CHAPTER 2 Staging Death CHAPTER 3 Disposing the Dead 5 CHAPTER 4 Disposing the Dead? CHAPTER 5 Animating the Dead 5 CONCLUSION 205 Notes 29 Works Cited 24 Index 25 List of Figures 1. Funerary altar of Cornelia Glyce. Vatican Museums. Rome. 2. Sarcophagus of Scipio Barbatus. Vatican Museums. Rome. 7 3. Sarcophagus of Scipio Barbatus (background). Vatican Museums. Rome. 68 4. Epitaph of Rufus. -

Latin Literature 1

Latin Literature 1 Latin Literature The Project Gutenberg EBook of Latin Literature, by J. W. Mackail Copyright laws are changing all over the world. Be sure to check the copyright laws for your country before downloading or redistributing this or any other Project Gutenberg eBook. This header should be the first thing seen when viewing this Project Gutenberg file. Please do not remove it. Do not change or edit the header without written permission. Please read the "legal small print," and other information about the eBook and Project Gutenberg at the bottom of this file. Included is important information about your specific rights and restrictions in how the file may be used. You can also find out about how to make a donation to Project Gutenberg, and how to get involved. **Welcome To The World of Free Plain Vanilla Electronic Texts** **eBooks Readable By Both Humans and By Computers, Since 1971** *****These eBooks Were Prepared By Thousands of Volunteers!***** Title: Latin Literature Author: J. W. Mackail Release Date: September, 2005 [EBook #8894] [Yes, we are more than one year ahead of schedule] [This file was first posted on August 21, 2003] Edition: 10 Latin Literature 2 Language: English Character set encoding: ISO−8859−1 *** START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK LATIN LITERATURE *** Produced by Distributed Proofreaders LATIN LITERATURE BY J. W. MACKAIL, Sometime Fellow of Balliol College, Oxford A history of Latin Literature was to have been written for this series of Manuals by the late Professor William Sellar. After his death I was asked, as one of his old pupils, to carry out the work which he had undertaken; and this book is now offered as a last tribute to the memory of my dear friend and master. -

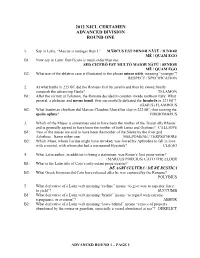

2012 Njcl Certamen Advanced Division Round One

2012 NJCL CERTAMEN ADVANCED DIVISION ROUND ONE 1. Say in Latin, “Marcus is younger than I.” MĀRCUS EST MINOR NĀTŪ / IUNIOR MĒ / QUAM EGO B1: Now say in Latin: But Cicero is much older than me. SED CICERŌ EST MULTŌ MAIOR NĀTŪ / SENIOR MĒ / QUAM EGO B2: What use of the ablative case is illustrated in the phrase minor nātū, meaning “younger”? RESPECT / SPECIFICATION 2. At what battle in 225 BC did the Romans first by javelin and then by sword finally vanquish the advancing Gauls? TELAMON B1: After the victory at Telamon, the Romans decided to counter-invade northern Italy. What general, a plebeian and novus homō, first successfully defeated the Insubrēs in 223 BC? (GAIUS) FLAMINIUS B2: What Insubrian chieftain did Marcus Claudius Marcellus slay in 222 BC, thus earning the spolia opīma? VIRIDOMARUS 3. Which of the Muses is sometimes said to have been the mother of the Trojan ally Rhesus and is generally agreed to have been the mother of both Linus and Orpheus? CALLIOPE B1: Two of the muses are said to have been the mother of the Sirens by the river god Achelous. Name either one. MELPOMENE / TERPSICHORE B2: Which Muse, whom Tacitus might have invoked, was forced by Aphrodite to fall in love with a mortal, with whom she had a son named Hyacinth? CL(E)IO 4. What Latin author, in addition to being a statesman, was Rome’s first prose writer? (MARCUS PORCIUS) CATO THE ELDER B1: What is the Latin title of Cato’s only extant prose treatise? DĒ AGRĪ CULTŪRĀ / DĒ RĒ RUSTICĀ B2: What Greek historian did Cato have released after he was captured by the Romans? POLYBIUS 5.