Challenges and Channels

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Script Épisode 1

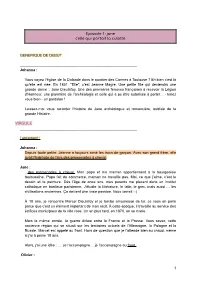

Episode 1 : jane celle qui portait la culotte GENERIQUE DE DEBUT _________________________________________________________ Johanna : Vous voyez l'église de la Dalbade dans le quartier des Carmes à Toulouse ? Eh bien c'est là qu'elle est née. En 1851. "Elle", c'est Jeanne Magre. Une petite fille qui deviendra une grande dame : Jane Dieulafoy. Une des premières femmes françaises à recevoir la Légion d'Honneur, une pionnière de l’archéologie et celle qui a pu être autorisée à porter… - tenez vous bien - un pantalon ! Laissez-moi vous raconter l'histoire de Jane archéologue et romancière, oubliée de la grande Histoire. VIRGULE _________________________________________________________ Lancement : Johanna : Depuis toute petite, Jeanne a toujours aimé les trucs de garçon. Avec son grand frère, elle avait l'habitude de faire des promenades à cheval. Jane : ...des promenades à cheval. Mon papa et ma maman appartiennent à la bourgeoisie toulousaine. Papa fait du commerce, maman ne travaille pas. Moi, ce que j'aime, c'est le dessin et la peinture. Dès l'âge de onze ans, mes parents me placent dans un Institut catholique en banlieue parisienne. J'étudie la littérature, le latin, le grec, mais aussi … les civilisations anciennes. Ça devient une vraie passion. Vous verrez ;-) À 18 ans, je rencontre Marcel Dieulafoy et je tombe amoureuse de lui. Je vous en parle parce que c'est un élément important de mon récit. À cette époque, il travaille au service des édifices municipaux de la ville rose. Un an plus tard, en 1870, on se marie. Mais la même année, la guerre éclate entre la France et la Prusse. -

TIPS for WOMEN TRAVELERS

101 TIPS for WOMEN TRAVELERS ® ® SM Since 1978 1 “ I am not the same having seen the moon shine on the other side of the world.” —Mary Anne Radmacher Artist & author A woman who has dedicated herself to inspiring and celebrating greatness in women, Mary Anne Radmacher is herself inspired by travel, as these words show. 2 Dear Traveler, When did travel first touch your life? For me, travel has been at my core since I was a little girl, sneaking a look at travel books under the covers when I was supposed to be sleeping. In the many years since, I’ve been privileged to visit countries on every continent, meeting wonderful people along the way. Today, my husband Alan and I own and co-chair the Grand Circle family of travel companies: Overseas Adventure Travel, Grand Circle Cruise Line, and Grand Circle Travel (see page 84 to learn more about our different types of travel). And I continue to realize that we can always learn from others when it comes to travel experience and advice. In these pages, you’ll find the best-of-the-best tips offered by OAT and Grand Circle female travelers, our online Travel Forum and Facebook followers, and associates and guides around the world. We are so grateful to all who contributed thoughts and ideas. I hope that this edition of 101 Tips for Women Travelers gives even the most experienced travelers new ideas for making the most of their trips. At the back of this volume, you’ll also find a number of resources that can help you prolong the joy of travel, including travel-related books, films, and Internet resources and apps. -

Tholozan Et La Perse *

Tholozan et la Perse * par Jean THÉODORIDÈS ** Les relations diplomatiques et culturelles entre la France et la Perse(l) remontent au XVIIe siècle avec les récits des voyages dans ce pays de Jean-Baptiste Tavernier (2) et de Jean Chardin (3). En 1715 l'ambassadeur de Perse Mehemet Riza Beg fut reçu en grande pompe à Versailles par Louis XIV (4). Les Lettres Persanes de Montesquieu (1721) constituent un reflet de cette vogue en France de la Perse et des Persans. En 1792 la Convention envoya au Proche-Orient (Empire Ottoman, Perse) une mis sion scientifique et politique composée de deux médecins naturalistes : Jean-Guillaume Bruguière et Guillaume-Antoine Olivier (4 bis). Leur voyage dura six ans et ils visitèrent la Perse (Hamadan, Téhéran, Ispahan, etc.) où régnait alors Aga Mohammed Khan, en 1796. Leurs observations concernent surtout l'histoire naturelle (botanique, zoologie). Napoléon 1er entretint des relations cordiales avec Fath Ali Shah qui régna de 1797 à 1833, ayant signé un traité d'amitié en 1807 et envoyé une mission dirigée par le Général Gardane dont J.M. Tancoigne publia le récit de voyage (4 ter). Jusqu'alors les rapports entre les deux pays étaient principalement d'ordre commer cial et militaire. Les relations médicales ne débutèrent que vers le milieu du siècle der nier lorsque Ernest Cloquet (1818-1854) fut appelé à Téhéran comme médecin du Shah (5). Lors de son arrivée en 1846 sévissait une épidémie de choléra dont il guérit une des épouses et une fille du monarque. Pour lui marquer sa reconnaissance, ce dernier fit de Cloquet son conseiller intime et le décora de l'ordre du Lion et du Soleil. -

This Article Is Published in European Encounters with Georgia in Past and Present

This article is published in European Encounters with Georgia in past and present. Special Issue of Anthropological Researches. Ed. by Françoise Companjen, VU Amsterdam University Press, 2014. George Sanikidze 19TH CENTURY FRENCH PERCEPTION OF GEORGIA: FROM THE TREATY OF FINKENSTEIN TO TRADE AND TOURISM. The 19th century is a turning point in the history of Georgia. After its incorporation into the Russian Empire, radical changes took place in the country. Europeans have taken an ever increasing interest in Georgia, specifically in its capital Tbilisi. This contribution discusses a change in France’s perception of Georgia and its capital during the nineteenth century. The nineteenth century French memoirs and records on Georgia can be divided into three basic groups. These groups reflect changes in the political and economic situation in the East-West relations, and thus a change in motives, which had immediate implications for Georgia. The first period coincides with the “Great Game” during the Napoleonic wars when Georgia inadvertently became part of France’s Eastern policy. The French sources on Georgia are comprised of so-called Treaty of Finkenstein between France and Persia, French newspapers (Le moniteur, Journal de l’Empire, Nouvelles étrangères...) reporting, and data on Georgia by French envoys in Persia (General Ange de Gardane (1766–1818), Amadée Jaubert (1779-1847), Joseph Rousseau (1780-1831), Camille Alphonse Trézel (1880- 1860). The second period was a time of taking interest economically in Georgia and its capital Tbilisi, which by then (especially under the so-called preferential tariff policy) had become a transit trade route for European goods going East, Iran in particular. -

XIX Saukune Saqartvelos Istoriasi Gardamtexi Epoqaa

George Sanikidze G. Tsereteli Institute of Oriental Studies, Ilia State University, Georgia BETWEEN EAST AND WEST: 19TH C. FRENCH PERCEPTION OF GEORGIA The 19th century is a turning point in the history of Georgia. After its incorporation into the Russian Empire radical changes took place in the country. Europeans have taken an ever increasing interest in Georgia, specifically in its capital Tbilisi. This article discusses a change in France’s perception of Georgia and its capital during the nineteenth century. The nineteenth century French memoirs and records on Georgia can be divided into three basic groups. These groups reflect changes in the political and economic situation in the East-West relations which had immediate implications for Georgia. The first period coincides with the “Great Game” during the Napoleonic wars when Georgia inadvertently became part of France’s Eastern policy. The French sources on Georgia are comprised of so- called Treaty of Finkenshtein between France and Persia, French newspapers (Le moniteur, Journal de l’Empire, Nouvelles étrangères...) reporting, and data on Georgia by French envoys in Persia (General Ange de Gardane (1766–1818), Amadée Jaubert (1779-1847), Joseph Rousseau (1780-1831), Camille Alphonse Trézel (1880-1860)...). The second period was a time of taking interest economically in Georgia and its capital Tbilisi, which by then (especially under the so-called preferential tariff policy) had become a transit trade route for European goods going East, Iran in particular. In this regard an invaluable source is the work by the first French consul in Tbilisi Chevalier Jacques François Gamba (1763-1833). Although the economic activity of France in the Caucasus relatively slowed after the preferential tariff was revoked (1831), many French still traveled to Georgia. -

Historical and Cultural Backgrounds of André Godard's Research Activities in Iran

Archive of SID Historical and Cultural Backgrounds of André Godard's Research Activities in Iran Hossein Soltanzadeh* Department of Architecture, Faculty Architecture and Urban Planning, Central Tehran Branch, Islamic Azad University, Tehran, Iran Received: 09 June 2020 - Accepted: 02 August 2020 Abstract Numerous foreign architects and researchers came to Iran from European countries in the first half of the contemporary century to carry out various activities. One of these figures was André Godard, whose cultural and research activities are of special importance in terms of variety and effectiveness. The present study hence aims to discuss the cultural and historical backgrounds that made it possible for André Godard to conduct different activities in Iran. The main objective of this study is to investigate the historical contexts and factors affecting André Godard‟s activities in Iran. The research question is as follows: What historical and cultural phenomena made a distinction between André Godard‟s cultural and research activities and those of other foreign architects in Iran in terms of breadth and diversity? The research theoretical foundation is based on the fact that the cultural and historical features of a country influence the activities of its architects and researchers in other counties. This was a qualitative historical study. The results showed that the frequency of historical and cultural studies on Iran with a positive attitude were higher in France compared to other European countries whose architects came to Iran during the Qajar and Pahlavi eras. In addition, the cultural policies of France in Iran were more effective than those of other foreign countries. -

Journal 2016 –

1 JOURNAL OF THE IRAN SOCIETY Editor: David Blow VOL. 2 NO. 15 CONTENTS Lectures: Javanmardi in the Iranian Tradition 7 17th Century Paintings from Safavid Isfahan 15 Travel Scholars’ Reports: Marc Czarnuszewicz 29 Book Reviews: Sweet Boy Dear Wife: Jane Dieulafoy in Persia 1881-1886 34 Memories of a Bygone Age: Qajar Persia and Imperial Russia 1853-1902 46 Nazi Secret Warfare in Occupied Persia. Espionage and Counter-intelligence in Occupied Persia. 49 Shiva Rahbaran – Writers Uncensored. 54 The Love of Strangers. 58 1a St Martin’s House, Polygon Road, London NW1 1QB Telephone : 020 7235 5122 Fax : 020 7259 6771 Web Site : www.iransociety.org Email : [email protected] Registered Charity No 248678 2 OFFICERS AND COUNCIL 2016 (as of the AGM held on 22 June 2016) President SIR RICHARD DALTON K.C.M.G. Vice-Presidents SIR MARTIN BERTHOUD K.C.V.O., C.M.G. MR M. NOËL-CLARKE MR B. GOLSHAIAN MR H. ARBUTHNOTT C.M.G. Chairman MR A. WYNN Hon. Secretary MR D.H.GYE Hon. Treasurer MR R. M. MACKENZIE Hon. Lecture Secretary MRS J. RADY Members of Council Dr F. Ala Dr M-A. Ala Mr S. Ala Mr D. Blow Hon J.Buchan Ms N Farzad Dr T. Fitzherbert Professor Vanessa Martin Dr A. Tahbaz 3 THE IRAN SOCIETY OBJECTS The objects for which the Society is established are to promote learning and advance education in the subject of Iran, its peoples and culture (but so that in no event should the Society take a position on, or take any part in, contemporary politics) and particularly to advance education through the study of the language, literature, art, history, religions, antiquities, usages, institutions and customs of Iran. -

Preliminary Program, AIS 2020: Salamanca, August 25–28Th 2020

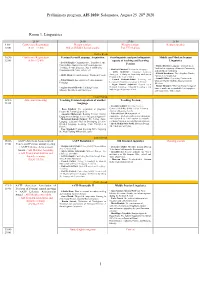

Preliminary program, AIS 2020: Salamanca, August 25–28th 2020 Room 1. Linguistics 25.08 26.08 27.08 28.08 8:30- Conference Registration Plenary session: Plenary session: Keynote speaker 10:00 (8:30 – 12:00) Old and Middle Iranian studies Iran-EU relations Coffee break 10:30- Conference Registration Persian Second Language Acquisition Sociolinguistic and psycholinguistic Middle and Modern Iranian 12:00 (8:30 – 12:00) aspects of teaching and learning Linguistics - Latifeh Hagigi: Communicative, Task-Based, and Persian Content-Based Approaches to Persian Language - Chiara Barbati: Language of Paratexts as Teaching: Second Language, Mixed and Heritage Tool for Investigating a Monastic Community - Mahbod Ghaffari: Persian Interlanguage Classrooms at the University Level in Early Medieval Turfan - Azita Mokhtari: Language Learning - Zohreh Zarshenas: Three Sogdian Words ( Strategies: A Study of University Students of (m and ryżי k .kי rγsי β יי Ali R. Abasi: Second Language Writing in Persian - Persian in the United States - Jamal J. Elias: Preserving Persian in the - Pouneh Shabani-Jadidi: Teaching and - Nahal Akbari: Assessment in Persian Language Ottoman World: Shahidi, Anqaravi and the learning the formulaic language in Persian Pedagogy Mevlevis - Negar Davari Ardakani: Persian as a - Rainer Brunner: Who was Franz Steingass? National Language, Minority Languages and - Asghar Seyed-Ghorab: Teaching Persian Some remarks on a remarkable lexicographer Multilingual Education in Iran Ghazals: The Merits and Challenges of Persian in the 19th century -

The Master Historian of the Middle East » Mosaic

6/10/2018 The Master Historian of the Middle East » Mosaic THE MASTER HISTORIAN OF THE MIDDLE EAST https://mosaicmagazine.com/response/2016/06/the-master-historian-of-the-middle-east/ An entire syllabus on the history of the Middle East could be compiled from the writings of Bernard Lewis. It will be a long time before the field will see another genius of his caliber. June 27, 2016 | Martin Kramer This is a response to The Return of Bernard Lewis, originally published in Mosaic in June 2016 It is gratifying that my essay in Mosaic should have prompted such moving tributes to Bernard Lewis from Robert Irwin, Itamar Rabinovich, Eric Ormsby, and Amir Taheri: distinguished scholars and writers whose friendships with him span many decades. And they are but a few of the many admirers who would have eagerly answered Mosaic’s call. This is all the more remarkable given that Books by Bernard Lewis. Martin Kramer. Lewis’s own contemporaries are gone. If Bernard is so beloved today by so many, it is because he readily assumed the role of a mentor to the young. I was a case in point, having first enrolled in Bernard’s class at Princeton as a twenty-two-year-old graduate student. He was then sixty, almost two full generations older, but within a month he had set me up with an assistantship, giving me a key to his office at the Institute for Advanced Study and tasking me with cataloguing incoming scholarly offprints. There, working after hours and on weekends, I would sit at his desk, marveling at the sheer volume and variety of the incoming mail and catching glimpses of the correspondence of a scholar with a global reputation. -

The Forerunners on Heritage Stones Investigation: Historical Synthesis and Evolution

heritage Review The Forerunners on Heritage Stones Investigation: Historical Synthesis and Evolution David M. Freire-Lista 1,2 1 Departamento de Geologia, Escola de Ciências da Vida e do Ambiente, Universidade de Trás-os-Montes e Alto Douro, 5001-801 Vila Real, Portugal; [email protected] 2 Centro de Geociências, Universidade de Coimbra, 3030-790 Coimbra, Portugal Abstract: Human activity has required, since its origins, stones as raw material for carving, con- struction and rock art. The study, exploration, use and maintenance of building stones is a global phenomenon that has evolved from the first shelters, manufacture of lithic tools, to the construction of houses, infrastructures and monuments. Druids, philosophers, clergymen, quarrymen, master builders, naturalists, travelers, architects, archaeologists, physicists, chemists, curators, restorers, museologists, engineers and geologists, among other professionals, have worked with stones and they have produced the current knowledge in heritage stones. They are stones that have special significance in human culture. In this way, the connotation of heritage in stones has been acquired over the time. That is, the stones at the time of their historical use were simply stones used for a certain purpose. Therefore, the concept of heritage stone is broad, with cultural, historic, artistic, architectural, and scientific implications. A historical synthesis is presented of the main events that marked the use of stones from prehistory, through ancient history, medieval times, and to the modern period. In addition, the main authors who have written about stones are surveyed from Citation: Freire-Lista, D.M. The Ancient Roman times to the middle of the twentieth century. Subtle properties of stones have been Forerunners on Heritage Stones discovered and exploited by artists and artisans long before rigorous science took notice of them and Investigation: Historical Synthesis explained them. -

The Architectural Order of Persian Talar Life of a Form

The Architectural Order of Persian Talar Life of a Form Ludovico Micara1 Tout est forme, et la vie même est une forme. Honoré de Balzac La forme … est d’abord une vie mobile dans un monde changeant. Les métamorphoses, sans fin, recommencent. Henri Focillon Abstract: the architectural order of the Persian talar, which characterized the most significant architecture of Safavid Persia and its capital Isfahan in the seventeenth century, condenses within its spaces a series of quality and characteristics that identify it as a recognizable and independent architectural form. This form syncretically collects and expresses a range of experiences and motives, that render the Persian architectural tradition and its continuity during at least 3000 years, an extraordinary unicum. The analysis of the persistence of the talar form to this day highlights the theme of vitality over time of certain architectural shapes and its meaning, whether overt or implied, almost independently of its temporary interpreters; perhaps proving and preluding a possible “life of forms” in architecture. Keywords: Architectural order, Forms, Talar, Hypostyle Hall, Persia, Safavid, Isfahan, Persepolis, the Arab-Islamic Mosque, Gunnar Asplund, Frank Lloyd Wright, Ludovico Quaroni, Norman Foster. The German naturalist, traveler and writer Engelbert Kaempfer, author in 1712 of the “relations, observations and descriptions of Persian things and farther Asia”2, contained in Amoenitatum exoticarum politico- physico-medicarum fasciculi V3, accurately illustrating the palaces and royal gardens of the Safavid Isfahan, avails himself of the opportunity to introduce and describe the talar palace (Fig. 1). Kaempfer distinguishes the two fundamental areas of the palatial structure of Isfahan, and more generally of the courts and royal residences of the Islamic world. -

STUDENTS, TEACHERS, and EDWARD SAID: TAKING STOCK of ORIENTALISM by Joshua Teitelbaum and Meir Litvak,* Translated from Hebrew by Keren Ribo

STUDENTS, TEACHERS, AND EDWARD SAID: TAKING STOCK OF ORIENTALISM By Joshua Teitelbaum and Meir Litvak,* translated from Hebrew by Keren Ribo Since the publication of Orientalism in 1978, Edward Said's critique has become the hegemonic discourse of Middle Eastern studies in the academy. While Middle Eastern studies can improve, and some part of Said's criticism is valid, it is apparent that the Orientalism critique has done more harm than good. Although Said accuses the West and Western researchers of "essentializing" Islam, he himself commits a similar sin when he writes that Western researchers and the West are monolithic and unchanging. Such a view delegitimizes any search for knowledge--the very foundation of the academy. One of Said 's greatest Arab critics, Syrian philosopher Sadiq Jalal al-Azm, attacked Said for the anti-intellectualism of this view. Since German and Hungarian researchers are not connected to imperialism, Said conveniently leaves them out of his critique. Said also ignores the positive contribution that researchers associated with power made to the understanding of the Middle East. Said makes an egregious error by negating any Islamic influence on the history of the region. His discursive blinders-- for he has created his own discourse--led him before September 11, 2001 to denigrate the idea that Islamist terrorists could blow up buildings and sabotage airplanes. Finally, Said's influence has been destructive: it has contributed greatly to the excessively politicized atmosphere in Middle Eastern studies that rejects a critical self-examination of the field, as well as of Middle Eastern society and politics. The study of the Middle East, or learning that was not integrated in the wider "Oriental studies," as this discipline was discipline of history.