ANGELS in DISGUISE” SERMON Rev

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Order of Worship 12 20 2020

December 20, 2020 Fourth Sunday of Advent Order of Worship Welcome and Call to Worship Rev. Dr. David D. Young Prelude An Advent Prelude Charles Callahan Linda Repking - flute, Dr. Hyunju Hwang - organ Lighting of the Fourth Advent Candle Opening Sentences Michael Moorhead Scripture Genesis 12: 1-4 Bell Carol O Come, O Come, Emmanuel Neighborhood Brass Rings Prayer O God, who in this Advent season speaks again the word of blessing which calls us to new faith journeys, help us to have ears to hear and eyes to see the unfolding of your promise in the coming of Jesus Christ our Lord. Amen. Lighting of the Fourth Advent Candle We light the fourth Advent candle which points to promise as we remember father Abraham who heard God’s voice and was not afraid to take the first step in faithful response to God’s promised tomorrow. Scripture Reading Matthew 1: 18-25 Now the birth of Jesus the Messiah took place in this way. When his mother Mary had been engaged to Joseph, but before they lived together, she was found to be with child from the Holy Spirit. Her husband Joseph, being a righteous man and unwilling to expose her to public disgrace, planned to dismiss her quietly. But just when he had resolved to do this, an angel of the Lord appeared to him in a dream and said, “Joseph, son of David, do not be afraid to take Mary as your wife, for the child conceived in her is from the Holy Spirit. She will bear a son, and you are to name him Jesus, for he will save his people from their sins.” All this took place to fulfill what had been spoken by the Lord through the prophet: “Look, the virgin shall conceive and bear a son, and they shall name him Emmanuel,” which means “God is with us.” When Joseph awoke from sleep, he did as the angel of the Lord commanded him; he took her as his wife, but had no marital relations with her until she had borne a son; and he named him Jesus.” December 20, 2020 Fourth Sunday of Advent Hymn of Preparation Angels We Have Heard on High Christopher Craig, David Sateren, Dr. -

Buffy & Angel Watching Order

Start with: End with: BtVS 11 Welcome to the Hellmouth Angel 41 Deep Down BtVS 11 The Harvest Angel 41 Ground State BtVS 11 Witch Angel 41 The House Always Wins BtVS 11 Teacher's Pet Angel 41 Slouching Toward Bethlehem BtVS 12 Never Kill a Boy on the First Date Angel 42 Supersymmetry BtVS 12 The Pack Angel 42 Spin the Bottle BtVS 12 Angel Angel 42 Apocalypse, Nowish BtVS 12 I, Robot... You, Jane Angel 42 Habeas Corpses BtVS 13 The Puppet Show Angel 43 Long Day's Journey BtVS 13 Nightmares Angel 43 Awakening BtVS 13 Out of Mind, Out of Sight Angel 43 Soulless BtVS 13 Prophecy Girl Angel 44 Calvary Angel 44 Salvage BtVS 21 When She Was Bad Angel 44 Release BtVS 21 Some Assembly Required Angel 44 Orpheus BtVS 21 School Hard Angel 45 Players BtVS 21 Inca Mummy Girl Angel 45 Inside Out BtVS 22 Reptile Boy Angel 45 Shiny Happy People BtVS 22 Halloween Angel 45 The Magic Bullet BtVS 22 Lie to Me Angel 46 Sacrifice BtVS 22 The Dark Age Angel 46 Peace Out BtVS 23 What's My Line, Part One Angel 46 Home BtVS 23 What's My Line, Part Two BtVS 23 Ted BtVS 71 Lessons BtVS 23 Bad Eggs BtVS 71 Beneath You BtVS 24 Surprise BtVS 71 Same Time, Same Place BtVS 24 Innocence BtVS 71 Help BtVS 24 Phases BtVS 72 Selfless BtVS 24 Bewitched, Bothered and Bewildered BtVS 72 Him BtVS 25 Passion BtVS 72 Conversations with Dead People BtVS 25 Killed by Death BtVS 72 Sleeper BtVS 25 I Only Have Eyes for You BtVS 73 Never Leave Me BtVS 25 Go Fish BtVS 73 Bring on the Night BtVS 26 Becoming, Part One BtVS 73 Showtime BtVS 26 Becoming, Part Two BtVS 74 Potential BtVS 74 -

Friday, 9/25/20 Announcements • the Jesuit's Dads Club Is Sponsoring A

Friday, 9/25/20 Announcements • The Jesuit’s Dads Club is sponsoring a Feeding Tampa Bay Mobile Pantry on Saturday, October 3rd at Hillsborough Community College. This is an opportunity for Jesuit students to volunteer alongside their fathers to help serve the hungry throughout the Tampa Bay area. The Dad’s Club is looking for 50-75 father-son pairs to help make this event a success. Interested volunteers should check the X2Vol bulletin board or email Coach Wood with any questions. • Auditions for The Masque’s fall production TWELVE INCOMPETENT JURORS will take place via Zoom today and Monday at 4pm. It is not too late to sign up, and no prior acting experience is required. To register, see the Masque Fall Play Auditions module on the Student Life Canvas page. • Yesterday, the Tiger Golf team, led by Carter Dill and Chase Johns, defeated Tampa Catholic by sweeping the Crusaders in what was their final meeting this season. Next up, the team will participate in The Lakewood Ranch Invitational on Monday. • Yesterday, the Jesuit Swimming and Diving team moved to 3-0 on the season by defeating Robinson, 145-26. Winners included: -200 Medley Relay: Liam Schindler, Nick Shaffer, Jordan Jansen, Sam Prabhakaran -200 Freestyle: Ryan Finster -200 IM: Sam Prabhakaran -50 Freestyle: Nick Shaffer -Diving: Sasha Fiola -100 Fly: Brayden Hohman -100 Freestyle: Jordan Jansen -500 Freestyle: Nick Shaffer -200 Freestyle Relay: Sam Prabhakaran, Ryan Finster, Sean Kenny, Erick Magalhaes -100 Backstroke: Aidan Clements -100 Breaststroke: Sam Prabhakaran -400 Freestyle Relay: Brayden Hohman, Liam Schindler, Jordan Jansen, Nick Shaffer The team looks to continue their dominance next Tuesday against Plant. -

The Vision Thing”: George H.W

“The Vision Thing”: George H.W. Bush and the Battle For American Conservatism 19881992 Paul Wilson A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of BACHELOR OF ARTS WITH HONORS DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN April 1, 2012 Advised by Professor Maris Vinovskis For my Grandfather, who financed this project (and my education). For my beautiful Bryana, who encouraged me every step of the way. Introduction............................................................................................................................................. 6 Chapter One: The Clash of Legacies.......................................................................................... 14 Chapter Two: The End of the Cold War and the New European Order ................ 42 Chapter Three: 1992 and the Making of Modern American Conservatism....... 70 Conclusion............................................................................................................................................ 108 Bibliography....................................................................................................................................... 114 4 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Many thanks to the University of Michigan library system for providing access to the material used in the making of this thesis. Thanks to Professor Maris Vinovskis, who provided invaluable knowledge and mentorship throughout the whole writing process. Much gratitude goes to Dr. Sigrid Cordell, who always found the resources I needed to complete this -

Fallen Angels: the Investment Opportunity

Fallen Angels: The investment opportunity Authors: Prof. Andrew Clare, Prof. Stephen Thomas, Dr. Nick Motson This document is for Professional Clients only in Dubai, Jersey, Guernsey, the Isle of Man and the UK, Professional Clients and Financial Advisers in Continental Europe and Qualifi ed Investors in Switzerland and is not for consumer use. Centre for Asset Management Research Cass Business School in cooperation with Invesco PowerShares September 2016 Table of content 1 What is a fallen angel? 3 2 What’s the potential investment opportunity? 3 - 4 2.1 The overreaction hypothesis 2.2 Institutional factors 2.3 Summary 3 Evidence of the impact on bond prices 4 - 8 4 How could investing in this idea fit into a portfolio? 8 - 10 5 Summary 10 References • Barron, M., A. Clare and S.H. Thomas, The information content of credit rating changes in the UK stock market, The Journal of Business Finance and Accounting, (1997), Vol. 24, 497-509. • Cantor, R., O. Ap Gwilym and S.H. Thomas, The Use of Credit Ratings in Investment Management in the U.S. and Europe, The Journal of Fixed Income, (Fall 2007), Vol. 17, No. 2: 13-26. • Clare, A. and S.H. Thomas, Winners and losers: UK evidence for the overreaction hypothesis, The Journal of Business Finance and Accounting, (October 1995), 961-973. • DeBondt, W.F.M. and R.H. Thaler (1985), Does the stock market overreact? Journal of Finance, Vol. 40, 793-805. • Hite, G. and A. Warga, The Effect of Bond-Rating Changes on Bond Price Performance, Financial Analysts Journal, Vol. -

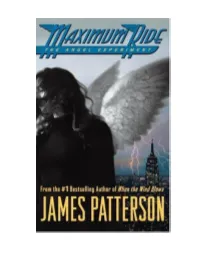

Maximum Ride T H E ANGEL EXPERIMENT

Maximum Ride T H E ANGEL EXPERIMENT James Patterson WARNER BOOKS NEW YORK BOSTON Copyright © 2005 by Suejack, Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote brief passages in a review. Warner Vision and the Warner Vision logo are registered trademarks of Time Warner Book Group Inc. Time Warner Book Group 1271 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10020 Visit our Web site at www.twbookmark.com First Mass Market Edition: May 2006 First published in hardcover by Little, Brown and Company in April 2005 The characters and events portrayed in this book are fictitious. Any similarity to real persons, living or dead, is coincidental and not intended by the author. Cover design by Gail Doobinin Cover image of girl © Kamil Vojnar/Photonica, city © Roger Wood/Corbis Logo design by Jon Valk Produced in cooperation with Alloy Entertainment Library of Congress Cataloguing-in-Publication Data Maximum Ride : the angel experiment / by James Patterson. — 1st ed. p.cm. Summary: After the mutant Erasers abduct the youngest member of their group, the "bird kids," who are the result of genetic experimentation, take off in pursuit and find themselves struggling to understand their own origins and purpose. ISBN: 0-316-15556-X(HC) ISBN: 0-446-61779-2 (MM) [1. Genetic engineering — Fiction. 2. Adventure and adventurers — Fiction.] 1. Title. 10 9876543 2 1 Q-BF Printed in the United States of America For Jennifer Rudolph Walsh; Hadley, Griffin, and Wyatt Zangwill Gabrielle Charbonnet; Monina and Piera Varela Suzie and Jack MaryEllen and Andrew Carole, Brigid, and Meredith Fly, babies, fly! To the reader: The idea for Maximum Ride comes from earlier books of mine called When the Wind Blows and The Lake House, which also feature a character named Max who escapes from a quite despicable School. -

When Tomorrow Starts Without Me Erica Shea Liupaeter When

When Tomorrow Starts Without Me Erica Shea Liupaeter When tomorrow starts without me, and I'm not there to see; If the sun should rise and find your eyes, all filled with tears for me; I wish so much you wouldn't cry, the way you did today, while thinking of the many things, we didn't get to say. I know how much you love me, as much as I love you, and each time that you think of me, I know you'll miss me too; But when tomorrow starts without me, please try to understand, that an Angel came and called my name, and took me by the hand, and said my place was ready, in heaven far above, and that I'd have to leave behind, all those I dearly love. But as I turned to walk away, a tear fell from my eye, for all life, I'd always thought, I didn't want to die. I had so much to live for, so much yet to do, it seemed almost impossible, that I was leaving you. I thought of all the yesterdays, the good ones and the bad, I thought of all the love we shared, and all the fun we had. If I could relive yesterday, just even for awhile, I'd say goodbye and kiss you and maybe see you smile. But then I fully realized, that this could never be, for emptiness and memories, would take the place of me. And when I thought of worldly things, I might miss come tomorrow, I thought of you, and when I did, my heart was filled with sorrow. -

The Last Seder

1 THE LAST SEDER By Jennifer Maisel This excerpt is copyrighted and for audition or classroom purposes only. For the full draft of the play or production rights please contact the author or her agent. Jennifer Maisel [email protected] REPRESENTATION: Susan Schulman [email protected] 6/03 2 THE STAGE - The set needs to imbue the audience members with a sense of how in this house stories are woven and lives move forward simultaneously. Minimal prop pieces can indicate a room - things pulling out of moving boxes that litter the house. The set and the lights need to facilitate the action moving forward without blackout, that some characters are continuing their lives and action onstage when they are not the ones currently in focus. In any home a family lives, at once, the same life and different lives. It is my intention that the play and its production reflect that. 3 CHARACTERS LILY PRICE - sixties, family matriarch MARVIN PRICE - seventies, her husband, suffering from Alzheimers JULIA PRICE - oldest daughter, mid thirties, very pregnant CLAIRE PRICE - second daughter, early thirties MICHELLE PRICE - third daughter, late twenties ANGEL PRICE - the youngest, early twenties -- HAROLD FREEDMAN - seventies, next door neighbor JANE - Julia’s lover JON - Claire’s fiancee KENT - late twenties, early thirties LUKE - of color, early twenties -- There is no intermission. 4 Man plans and God laughs -yiddish saying 5 BLACK (Marvin stands in his own light) MARVIN Why am I in some place with angels? (The rhythmic lulling sounds of a TRAIN on the tracks - -lights crossfade to Michelle-) PENN STATION MICHELLE Ummm, excuse me - hi? - look, I know you don’t know me, but you look like someone who might..might be open to a complete stranger asking you...I’m not some psycho- chick, in case you’re thinking I am which I’m sure you are - here’s my license, so you know I’m me.. -

A History of Ballet. by Jennifer Homans

Books Apollo’s Angels: A History of Ballet. By Jennifer Homans. New York: Random House, 2010; 672 pp.; illustrations. $20.00 paper. I have long thought a social history of ballet would be a good idea — perhaps something modeled after Arnold Hauser’s classic Social History of Art (1951). Apollo’s Angels reviews four centuries of ballet history with a focus on tech- nique and styles that are strongly tied to national identity. Stories of the dancers and choreographers are interwoven with plot outlines from ballet libretti and thumbnail sketches of major and minor historical events. But, although impressive for its vast coverage, the book tends to be unreliable in its analysis and contradictory in its methodology. From the geometrical dances of 1581 in Le Ballet Comique de la Reine to Nijinsky’s American tour in 1916, many claims are compromised by the findings of recent scholar- ship, which the author has apparently not consulted. An agenda drives this chronicle. Jennifer Homans separates the wheat from the chaff of history by distinguishing what she considers to be “pure” ballet. This leads to value judgments, not social history. It is revealing to understand what Homans means by pure: ballet that does not tell a story, but evokes an essence or a feeling; ballet that exudes a godlike nobility; ballet that is rooted in highly conservative ideologies. Stylistic purity is above all aristocratic, conservative, and, at her own admission, “stuck” in the past: “It was stuck, but that also meant that it marked a historical place and fiercely guarded the aristocratic principle that was its guid- ing force” (264). -

Pre-Seed Fund Capitalization Program 2014

Pre-Seed Fund Capitalization Program 2014 Proposal Evaluation Report Prepared by Invantage Group June 2014 Pre-Seed Fund Capitalization Program 2014 Table of Contents Table of Contents ...............................................................................................................................2 Introduction ......................................................................................................................................3 Ohio Third Frontier ............................................................................................................................3 Vision & Objectives ................................................................................................................................... 3 Pre-Seed Fund Capitalization Program ................................................................................................3 Program Purpose ...................................................................................................................................... 3 Fund Expectations .................................................................................................................................... 3 External Evaluators ................................................................................................................................... 4 Proposal Evaluation Scope and Criteria .................................................................................................... 4 Evaluation Process ................................................................................................................................... -

Rob Mathes Evening Train

EVENING TRAIN ROB MATHES Page 2 Page 3 01 Prelude (Evening Train) Gonna ride the evening train Gonna ride it all night long Gonna hear the whistle blow Then I know I’m gone No turning back Evening train rushing down the track ARTIST : 000000000000 DESIGNER : 000000000000 TITLE : 000000000000 COMPANY : 000000000000 cd301c • cd booklet – full spread • ccg6.0 • CATALOGUE No. : 000000000000 revised 12 apr 2000 CONTACT No. : 000000000000 PAGES : 000000000000 DATE : 000000000000 FORMAT : 000000000000 REVISION : 000000000000 PAGE 4 PAGE 5 Fatman Come tomorrow, I got alot of plans Come tomorrow, I’ll change my world Come tomorrow, I’ll know what to do and when to do it And I’ll remove the sword from the stone It’s a funny misunderstanding I carry around in my head CHORUS A conundrum that couldn’t be true but tonight, this eternal night In a world that doesn’t lack for trouble and dread which seems to last forever I’ve been chosen for the chosen few stay with me, if you would, CHORUS if you please, if you can And I remember every night I’d pray spend some time with a fatman For a miracle to come my way Come tomorrow, I’m gonna move myself And now it seems I find myself on a regular basis Come tomorrow, I’ll seek a cure Resting in your arms at the end of the day but today, I guess I like sitting here End Of The Day I am looking at pictures taken of you and I and soon I’ll fall asleep for sure There is love in your eyes no doubt CHORUS But how can beauty and grace possibly be mine? I want to cross over No I can’t quite figure it out I want to cross -

FORDHAM CENTER on RELIGION and CULTURE Apocalypse Now: America’S Fascination with Doomsday and Why It Matters

The Fordham Center On Religion and Culture www.fordham.edu/ReligCulture 1 FORDHAM CENTER ON RELIGION AND CULTURE Apocalypse Now: America’s Fascination with Doomsday and Why It Matters Fordham University | Lincoln Center Campus 140 West 62nd Street | McNally Amphitheater Wednesday, September 12, 2012 — 6:00–8:00 p.m. Moderator Kurt Andersen NPR and WNYC, host of Studio 360 and King’s County; author of True Believers Panelists Elaine Pagels Princeton University, author of Revelations: Visions, Prophecy and Politics in the Book of Revelation J. Hoberman Film critic and author of An Army of Phantoms and Film after Film Andrew Delbanco Columbia University, author of The Puritan Ordeal and The Death of Satan JIM McCARTIN: Good evening. I am Jim McCartin of the Fordham Center on Religion and Culture, and it’s my great pleasure this evening to welcome you to Fordham University’s Lincoln Center campus. Thank you all for joining us. Our first forum this academic year brings together an exceptional panel to explore why we Americans are so drawn to apocalyptic scenarios. If we are known the world over for our persistent optimism, for our dreams of prosperity, why are we also so enamored with the end times? Does this fascination with Doomsday somehow distinguish us from other nations of the world? And how might our visions of destruction, subtly or not so subtly, shape who we are and how we behave? Certainly, religious visions of the end times, drawn from biblical admonitions to be attentive to signs and wonders, these biblical visions remain alive and well in the United States today.