Memory for Emotional Faces in Major Depression 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Obituary Peter Payne 2017

Professor Peter Payne It is with great sadness that Council reports the death of our distinguished and long serving President, Professor Peter Payne. Peter died on 10 January 2017, aged 87 years. A well attended service of committal was held at Aberdeen Crematorium on 20 th January, allowing many friends and colleagues to offer their condolences to Enid and their son and daughter, Simon and Samantha. They each contributed moving and frequently amusing recollections of their father, sympathetically read by the minister, Deaconess Marion Stewart. Peter was a Londoner whose academic path took him to Nottingham University where, in 1951, he graduated in the new and minority discipline of Economic History. His mentor was Professor David Chambers, who then set Peter on his research for his PhD, gained in 1954, and later published in 1961 as Rubber and Railways in the Nineteenth Century; A Study of the Spencer Papers, 1853 – 1891 . He had begun as he was to continue in his career, his scholarship founded on expert analysis of business records, and demonstrating their significance in understanding wider issues of economic and social development. His successful PhD launched him into two years of research at Johns Hopkins, this producing in 1956 a fine detailed study of The Savings Bank of Baltimore, 1818 – 1866 co-authored with Lance Davis. This was a spectacular start to an academic career in the new and relatively small discipline of Economic History, but building it had to wait, as National Service drew Peter into two years in the Royal Army Educational Corps. There he had the unusual experience of serving for a time on the staff of a military detention barracks. -

THE UNIVERSITY of ABERDEEN and the ROBERT GORDON UNIVERSITY MILITARY EDUCATION COMMITTEE

THE UNIVERSITY OF ABERDEEN and THE ROBERT GORDON UNIVERSITY MILITARY EDUCATION COMMITTEE Minutes of the Meeting held in the University of Aberdeen on 7 December 2009 Present: Professor T Salmon (Convener), Professor D Alexander, Squadron Leader K Block (representing Squadron Leader Gusterson), Professor J Broom, Ms C Buchanan, Dr A Clarke, Professor R Flin, Dr D Galbreath, Dr J Grieve, Wing Commander M Henderson, Lieutenant M Hutchinson, Mr J Lemon, Chief Petty Officer Mitchell, Professor P Robertson, Lieutenant Colonel K Wardner; with Ms Y Gordon (Clerk) Apologies: Principals Rice and Pittilo, Brigadier H Allfrey, Mr P Fantom, Wing Commander Kennedy and Lieutenant A Rose. The Convener invited members to introduce themselves and welcomed the following members who were attending for the first time: Professor Broom, Lieutenant Colonel Wardner, Lieutenant Hutchinson. He went on to inform the Committee of the sad news that Dr Molyneaux had passed away in the Spring. The Convener also thanked the former Clerk to the Committee, Mr Duggan, who had served as Clerk for many years. FOR DISCUSSION 1. Minutes The Committee approved the Minutes of the Meeting held on 1 December 2008 (copy filed as MEC09/1) 2. Unit Progress Reports URNU 2.1 The Committee considered a report from the Universities Royal Naval Unit, January – December 2009. (copy filed as MEC09/2a) 2.2 Lieutenant Hutchinson reported that 29 new students had been recruited, with a good cohort of 25 remaining. Unit strength currently stood at 51, at full capacity, and was split 24 male to 27 female. The Unit’s summer deployment of eight weeks duration was in the South H:\My documents\Policy Zone\Committe Minutes\Military Education1 Committee\Minutes7Dec09.doc Coast of England and included a visit to Greenwich and London. -

University of Aberdeen, Aberdeen, Scotland

UNIVERSITY OF WISCONSIN EAU CLAIRE ENTER FOR NTERNATIONAL DUCATION C I E Study Abroad UNIVERSITY OF ABERDEEN, ABERDEEN, SCOTLAND 2020 Program Guide ABLE OF ONTENTS Sexual Harassment and “Lad Culture” in the T C UK ...................................................................... 12 Academics .............................................................. 5 Emergency Contacts ...................................... 13 Pre-departure Planning .................................... 5 911 Equivalent in the UK ................................ 13 Graduate Courses ............................................. 5 Marijuana and other Illegal Drugs ................. 13 Credits and Course Load ................................. 5 Required Documents .......................................... 13 Registration at Aberdeen .................................. 5 Visa ................................................................... 13 Class Attendance .............................................. 5 Why Can’t I fly through Ireland? .................... 14 Grades ................................................................ 5 Visas for Travel to Other Countries .............. 14 Aberdeen & UWEC Transcripts ....................... 6 Packing Tips ........................................................ 14 UK Academic System ....................................... 6 Weather ............................................................ 14 Service-Learning ............................................... 8 Clothing ............................................................ -

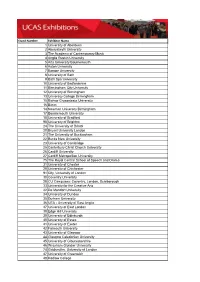

Stand Number Exhibitor Name 1 University of Aberdeen 2

Stand Number Exhibitor Name 1 University of Aberdeen 2 Aberystwyth University 3 The Academy of Contemporary Music 4 Anglia Ruskin University 5 Arts University Bournemouth 6 Aston University 7 Bangor University 8 University of Bath 9 Bath Spa University 10 University of Bedfordshire 11 Birmingham City University 12 University of Birmingham 13 University College Birmingham 15 Bishop Grosseteste University 16 Bimm 14 Newman University Birmingham 17 Bournemouth University 18 University of Bradford 98 University of Brighton 24 The University of Bristol 20 Brunel University London 21 The University of Buckingham 22 Bucks New University 23 University of Cambridge 25 Canterbury Christ Church University 26 Cardiff University 27 Cardiff Metropolitan University 75 The Royal Central School of Speech and Drama 31 University of Chester 29 University of Chichester 91 City, University of London 30 Coventry University 28 CU Campuses: Coventry, London, Scarborough 33 University for the Creative Arts 32 De Montfort University 34 University of Dundee 35 Durham University 36 UEA - University of East Anglia 37 University of East London 38 Edge Hill University 39 University of Edinburgh 40 University of Essex 41 University of Exeter 42 Falmouth University 43 University of Glasgow 44 Glasgow Caledonian University 45 University of Gloucestershire 46 Wrexham Glyndwr University 74 Goldsmiths, University of London 47 University of Greenwich 48 Hadlow College 49 Harper Adams University 50 Hartpury College and University Centre 51 Heriot-Watt University 52 University -

Discovery Research Portal

University of Dundee Novel biomarkers for risk stratification of Barrett's oesophagus associated neoplastic progression-epithelial HMGB1 expression and stromal lymphocytic phenotype Porter, Ross J.; Murray, Graeme I.; Brice, Daniel P.; Petty, Russell D.; McLean, Mairi H. Published in: British Journal of Cancer DOI: 10.1038/s41416-019-0685-1 Publication date: 2020 Document Version Peer reviewed version Link to publication in Discovery Research Portal Citation for published version (APA): Porter, R. J., Murray, G. I., Brice, D. P., Petty, R. D., & McLean, M. H. (2020). Novel biomarkers for risk stratification of Barrett's oesophagus associated neoplastic progression-epithelial HMGB1 expression and stromal lymphocytic phenotype. British Journal of Cancer, 122(4), 545-554. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41416-019- 0685-1 General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in Discovery Research Portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from Discovery Research Portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain. • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal. Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, -

School of Dentistry

School of Dentistry http://dentistry.dundee.ac.uk/ Vacancy CLINICAL RESEARCH FELLOW/ HONORARY SPECIALTY REGISTRAR in RESTORATIVE DENTISTRY NIHR HTA SCRIPT & PIP Trials Full Time Salary scale - £35,958 to £53,280 Informal enquiries are welcomed and intending applicants who would like to discuss the post further should contact Professor Jan Clarkson, [email protected], Professor David Ricketts [email protected] Dr Pauline Maillou(TPD) [email protected] Successful applicants will be subject to health clearance and the appropriate disclosure checks across the UK. Interviews will be held on: TBC Closing date: TBC The University of Dundee is committed to equal opportunities and welcomes applications from all sections of the community. School of Dentistry University of Dundee Level 9, Dundee Dental School Park Place Dundee, Scotland DD1 4HN http://dentistry.dundee.ac.uk/ Further Particulars 1. Job Title and Reporting Job Title: Clinical Research Fellow/Honorary Specialty Registrar in Restorative Dentistry Reporting to: Professor Jan Clarkson, Co-Chief Investigator, SCRIPT & PIP and TPD Staff Responsible for: n/a Duration of employment: Funded for up to 8 years 2. Job Purpose There are two elements to this post: Academic training by supporting the National Institute for Health Research’s HTA Programme SCRIPT Trial (17/127/07) and the PIP Trial (12/923/30) and completing a higher research degree Specialty training in Restorative Dentistry This is an exciting opportunity for qualified dentists looking for a stimulating -

Effectiveness of First Dose of COVID-19 Vaccines Against Hospital Admissions in Scotland: National Prospective Cohort Study of 5.4 Million People

This is a preprint and has not yet been peer reviewed Effectiveness of first dose of COVID-19 vaccines against hospital admissions in Scotland: national prospective cohort study of 5.4 million people Dr Eleftheria Vasileiou PhD, Usher Institute, The University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, EH8 9AG, UK, [email protected], Tel: 077 3296 1139 (Corresponding author)* Professor Colin R Simpson PhD, School of Health, Wellington Faculty of Health, Victoria University of Wellington, NZ and Usher Institute, University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, UK* Professor Chris Robertson PhD, Department of Mathematics and Statistics, University of Strathclyde, Glasgow, UK and Public Health Scotland, Glasgow, UK* Dr Ting Shi PhD, Usher Institute, The University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, UK* Dr Steven Kerr PhD, Usher Institute, The University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, EH8 9AG, UK* Dr Utkarsh Agrawal PhD, School of Medicine, University of St. Andrews, St Andrews, UK Mr Ashley Akbari, Population Data Science MSc, Swansea University Medical School, Swansea, UK Dr Stuart Bedston PhD, Population Data Science, Swansea University Medical School, UK Mrs Jillian Beggs, PPIE Lead, BREATHE – The Health Data Research Hub for Respiratory Health, UK Dr Declan Bradley MD, Queen’s University Belfast / Public Health Agency Mr Antony Chuter FRCGP (Hon) Lay member, Usher Institute, The University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, UK Prof Simon de Lusignan MD, Nuffield Dept Primary Care Health Sciences, University of Oxford, UK Dr Annemarie B Docherty PhD, Usher Institute, The University -

North American Student Guide

Study in Scotland A guide for North American students abdn.ac.uk/international University of Aberdeen Founded in 1495, the University of Aberdeen is the fifth oldest university in the English-speaking world. Today, the university has 14,000 students, from over 133 countries around the world, undertaking undergraduate and postgraduate degree programmes, across the Arts and Humanities, Business, Law, Science and Engineering and the Medical Sciences. Rankings and Reputation Scholars associated with the University alumni founded the university include five Nobel Prize College of William and Mary winners, and the inventor of the in the US, and the University modern MRI machine of Hong Kong We established the first Chair Law School ranked 12th in the UK of Medicine in the English out of more than 90 law schools speaking world in 1497 (Times Good University Guide, 2015) Fifth oldest university in the One of the top 10 Beautiful English-speaking world Historic Universities (QS Top Universities website, 2014) 2 UNIVERSITY OF ABERDEEN Academic Structure Arts and Social Sciences Business School Teaching and research at the School of Divinity, History and Philosophy University of Aberdeen is School of Education organised across 12 Schools, School of Language, Literature, Music and Visual Culture which encompass a broad range School of Law of disciplines: School of Social Sciences Life Sciences and Medicine School of Biological Sciences School of Medicine, Medical Sciences and Nutrition School of Psychology Physical Sciences School of Engineering School of Geosciences School of Natural and Computing Sciences 3 The £57million Sir Duncan Rice Library opened in 2012 4 UNIVERSITY OF ABERDEEN Campus Contrasting stunning History and Heritage • King’s College with its crown tower architecture and and chapel: the symbolic centre of historical charm with our growing campus landmark building • Medieval St Machar’s Cathedral – completed in 1530, there has been design, our campus a place of worship in the area since epitomises both the around 580 A.D. -

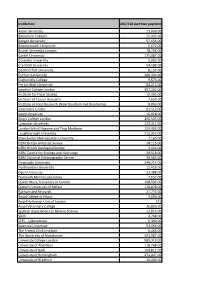

2017-18 Block Grant Awards – Part Two Payments

Institution 2017/18 part two payment Aston University 11,000.00 Babraham Institute 15,095.00 Bangor University 57,656.00 Bournemouth University 5,672.00 Brunel University London 78,766.00 Cardiff University 175,087.00 Coventry University 9,083.00 Cranfield University 54,588.00 De Montfort University 8,137.00 Durham University 200,334.00 Goldsmiths College 9,573.00 Heriot-Watt University 84,213.00 Imperial College London 357,202.00 Institute for Fiscal Studies 10,303.00 Institute of Cancer Research 7,620.00 Institute of Food Research (Now Quadram Inst Bioscience) 8,853.00 John Innes Centre 63,512.00 Keele University 16,918.00 King's College London 296,503.00 Lancaster University 123,311.00 London Sch of Hygiene and Trop Medicine 153,402.00 Loughborough University 212,352.00 Manchester Metropolitan University 7,165.00 NERC British Antarctic Survey 28,115.00 NERC British Geological Survey 3,424.00 NERC Centre for Ecology and Hydrology 24,518.00 NERC National Oceanography Centre 26,992.00 Newcastle University 248,714.00 Northumbria University 12,456.00 Open University 31,388.00 Plymouth Marine Laboratory 7,657.00 Queen Mary, University of London 198,434.00 Queen's University of Belfast 110,878.00 Rothamsted Research 27,772.00 Royal College of Music 3,690.00 Royal Holloway, Univ of London 215 Royal Veterinary College 26,890.00 Scottish Association For Marine Science 12,814.00 SRUC 4,768.00 STFC - Laboratories 5,390.00 Swansea University 51,494.00 The Francis Crick Institute 6,466.00 The University of Manchester 591,987.00 University College -

UK Student Visas

For up to date information on changes to the UK student immigration system, please visit the UK Border Agency (UKBA) website at www.ukba.homeoffice.gov.uk Scotland has 20 world class institutions to choose from*, for additional information on Scotland’s universities and specialist institutions please follow the following links: University of Aberdeen Open University in Scotland www.abdn.ac.uk www.open.ac.uk University of Abertay Dundee Queen Margaret University www.abertay.ac.uk www.qmu.ac.uk University of Dundee Robert Gordon University www.dundee.ac.uk www.rgu.ac.uk University of Edinburgh Royal Conservatoire of Scotland www.ed.ac.uk (known as the Royal Scottish Academy of Music & Drama until 1st September 2011) Edinburgh College of Art www.rcs.ac.uk www.eca.ac.uk Scottish Agricultural College (SAC) Edinburgh Napier University www.sac.ac.uk www.napier.ac.uk UK student visas: University of St Andrews University of Glasgow www.st-andrews.ac.uk www.glasgow.ac.uk University of Stirling A pledge of support for international Glasgow Caledonian University www.stir.ac.uk www.gcu.ac.uk students studying in Scotland. University of Strathclyde The Glasgow School of Art www.strath.ac.uk www.gsa.ac.uk University of the West of Scotland Heriot-Watt University, Edinburgh www.uws.ac.uk Going to a different country to study www.hw.ac.uk can be daunting, but you’ll find an University of the Highlands and Islands especially warm welcome in Scotland. www.uhi.ac.uk We enjoy sharing our unique and vibrant culture as well as our passion for world- leading research and teaching expertise. -

MRC-NIHR TMRP Trial Conduct Working Group Remit Co-Leads: Kerry Hood (Cardiff University) and Katie Gillies (University of Aberdeen)

MRC-NIHR TMRP Trial Conduct Working Group Remit Co-leads: Kerry Hood (Cardiff University) and Katie Gillies (University of Aberdeen). Objectives The overall aim of the Trial Conduct Working Group is to facilitate networking and collaborative research across the trials methodology community. The working group will aim to provide a forum to facilitate the development of improvements across key aspects of trial conduct and will seek to minimise duplication of effort within relevant areas. Trial Conduct is considered to cover what happens from study set-up to reporting of results. Although this can be influenced by trial design, it is not about design per se, but will consider the broader perspectives and influences (e.g. social and ethical) on trial conduct. Specific objectives of the group will be to: encourage and promote maximising value of funded studies through the use of SWATs; generate evidence to support decisions about future trial conduct; develop approaches to get evidence into practice in trial conduct; build capacity in methods research within the area of trial conduct. The new TMRP Trial Conduct Working Group, formed from and extending the previous MRC HTMR Trial Conduct and Recruitment Working Groups, will focus activities across areas which already have significant energy and traction behind them. Research areas to target: Recruitment to trials (Informed by the PRioRiTY I research agenda) Retention to trials (Informed by the PRioRiTY II research agenda) Qualitative research within trial conduct (e.g. generation of good working practice documents, costing models, connectivity and learning across existing data sets, capacity building, etc) Site selection and training (e.g. -

University of Aberdeen Erasmus Contact Information Sheet

UNIVERSITY OF ABERDEEN ERASMUS CONTACT INFORMATION SHEET Name of Institution University of Aberdeen Institution Code UK ABERDEE01 Vice-Chancellor Professor I Diamond WWW Address http://www.abdn.ac.uk INSTITUTIONAL CONTACT DETAILS Institutional ERASMUS Coordinator: Dr Shona Potts main contact for all queries, nominations, correspondence re bilateral agreements etc. Address ERASMUS Unit (NB: NEW ADDRESS) The Hub (2nd Floor) Elphinstone Road University of Aberdeen Aberdeen AB24 3TU, UK Telephone +44 1224 273664 Fax +44 1224 272109 E-mail [email protected] WWW Address http://www.abdn.ac.uk/erasmus ACCOMMODATION OFFICE Telephone +44 1224 273502 Fax +44 1224 272022 WWW Address http://www.abdn.ac.uk/accommodation DISABILITY ADVISERS Address The Hub Elphinstone Road University of Aberdeen Aberdeen AB24 3TU, UK Telephone +44 1224 273935 E-mail [email protected] WWW Address http://www.abdn.ac.uk/central/disabilities FINAL APPLICATION DEADLINES (NO LATE APPLICATIONS ACCEPTED) 1st semester/Full Year 1st June 2nd Semester 1st November All applicants must be nominated to the University of Aberdeen by their home university. No application will be accepted from students for whom a nomination e-mail has not been received An e-mail must be sent to [email protected] containing the following information: 1. Applicant’s name 2. Applicant’s e-mail address 3. Proposed length of stay 4. Subject area SEMESTER DATES 2011/2012 1st Semester Registration & Teaching Tuesday 20 September 2011 – Friday 16 December 2011 1st Semester Exams Saturday 14 January 2012 – Friday 27 January 2012 2nd Semester Registration & Teaching Monday 30 January 2012 – Friday 23 March 2012 Monday 16 April 2012 – Friday 11 May 2012 2nd Semester Exams Saturday 19 May 2012 – Friday 8 June 2012 APPLICATION PROCESS: INCOMING ERASMUS STUDENTS Nominations All applicants must be nominated to the University of Aberdeen by their home university.