Record Repositories in British Universities

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Obituary Peter Payne 2017

Professor Peter Payne It is with great sadness that Council reports the death of our distinguished and long serving President, Professor Peter Payne. Peter died on 10 January 2017, aged 87 years. A well attended service of committal was held at Aberdeen Crematorium on 20 th January, allowing many friends and colleagues to offer their condolences to Enid and their son and daughter, Simon and Samantha. They each contributed moving and frequently amusing recollections of their father, sympathetically read by the minister, Deaconess Marion Stewart. Peter was a Londoner whose academic path took him to Nottingham University where, in 1951, he graduated in the new and minority discipline of Economic History. His mentor was Professor David Chambers, who then set Peter on his research for his PhD, gained in 1954, and later published in 1961 as Rubber and Railways in the Nineteenth Century; A Study of the Spencer Papers, 1853 – 1891 . He had begun as he was to continue in his career, his scholarship founded on expert analysis of business records, and demonstrating their significance in understanding wider issues of economic and social development. His successful PhD launched him into two years of research at Johns Hopkins, this producing in 1956 a fine detailed study of The Savings Bank of Baltimore, 1818 – 1866 co-authored with Lance Davis. This was a spectacular start to an academic career in the new and relatively small discipline of Economic History, but building it had to wait, as National Service drew Peter into two years in the Royal Army Educational Corps. There he had the unusual experience of serving for a time on the staff of a military detention barracks. -

THE UNIVERSITY of ABERDEEN and the ROBERT GORDON UNIVERSITY MILITARY EDUCATION COMMITTEE

THE UNIVERSITY OF ABERDEEN and THE ROBERT GORDON UNIVERSITY MILITARY EDUCATION COMMITTEE Minutes of the Meeting held in the University of Aberdeen on 7 December 2009 Present: Professor T Salmon (Convener), Professor D Alexander, Squadron Leader K Block (representing Squadron Leader Gusterson), Professor J Broom, Ms C Buchanan, Dr A Clarke, Professor R Flin, Dr D Galbreath, Dr J Grieve, Wing Commander M Henderson, Lieutenant M Hutchinson, Mr J Lemon, Chief Petty Officer Mitchell, Professor P Robertson, Lieutenant Colonel K Wardner; with Ms Y Gordon (Clerk) Apologies: Principals Rice and Pittilo, Brigadier H Allfrey, Mr P Fantom, Wing Commander Kennedy and Lieutenant A Rose. The Convener invited members to introduce themselves and welcomed the following members who were attending for the first time: Professor Broom, Lieutenant Colonel Wardner, Lieutenant Hutchinson. He went on to inform the Committee of the sad news that Dr Molyneaux had passed away in the Spring. The Convener also thanked the former Clerk to the Committee, Mr Duggan, who had served as Clerk for many years. FOR DISCUSSION 1. Minutes The Committee approved the Minutes of the Meeting held on 1 December 2008 (copy filed as MEC09/1) 2. Unit Progress Reports URNU 2.1 The Committee considered a report from the Universities Royal Naval Unit, January – December 2009. (copy filed as MEC09/2a) 2.2 Lieutenant Hutchinson reported that 29 new students had been recruited, with a good cohort of 25 remaining. Unit strength currently stood at 51, at full capacity, and was split 24 male to 27 female. The Unit’s summer deployment of eight weeks duration was in the South H:\My documents\Policy Zone\Committe Minutes\Military Education1 Committee\Minutes7Dec09.doc Coast of England and included a visit to Greenwich and London. -

Memory for Emotional Faces in Major Depression 1

Memory for emotional faces in major depression 1 Running title: MEMORY FOR EMOTIONAL FACES IN MAJOR DEPRESSION Word Count: 4251 (excluding the abstract, references and tables) Memory for emotional faces in major depression following judgement of physical facial characteristics at encoding Nathan Ridout Aston University, Birmingham, UK Barbara Dritschel University of St Andrews, UK Keith Matthews and Maureen McVicar University of Dundee, UK Ian C. Reid University of Aberdeen, UK Ronan E. O’ Carroll University of Stirling, UK Address for correspondence: Dr Nathan Ridout Clinical and Cognitive Neurosciences Research Group School of Life and Health Sciences Aston University Birmingham, B7 4ET Tel: (+44 121) 2044162 Fax: (+44 121) 2044090 Email: [email protected] Memory for emotional faces in major depression 2 Abstract The aim of the present study was to establish if patients with major depression (MD) exhibit a memory bias for sad faces, relative to happy and neutral, when the affective element of the faces is not explicitly processed at encoding. To this end, 16 psychiatric outpatients with MD and 18 healthy, never-depressed controls (HC) were presented with a series of emotional faces and were required to identify the gender of the individuals featured in the photographs. Participants were subsequently given a recognition memory test for these faces. At encoding, patients with MD exhibited a non-significant tendency towards slower gender identification (GI) times, relative to HC, for happy faces. However, the GI times of the two groups did not differ for sad or neutral faces. At memory testing, patients with MD did not exhibit the expected memory bias for sad faces. -

North East Scotland

Employment Land Audit 2018/19 Aberdeen City Council Aberdeenshire Council Employment Land Audit 2018/19 A joint publication by Aberdeen City Council and Aberdeenshire Council Executive Summary 1 1. Introduction 1.1 Purpose of Audit 5 2. Background 2.1 Scotland and North East Scotland Economic Strategies and Policies 6 2.2 Aberdeen City and Shire Strategic Development Plan 7 2.3 Aberdeen City and Aberdeenshire Local Development Plans 8 2.4 Employment Land Monitoring Arrangements 9 3. Employment Land Audit 2018/19 3.1 Preparation of Audit 10 3.2 Employment Land Supply 10 3.3 Established Employment Land Supply 11 3.4 Constrained Employment Land Supply 12 3.5 Marketable Employment Land Supply 13 3.6 Immediately Available Employment Land Supply 14 3.7 Under Construction 14 3.8 Employment Land Supply Summary 15 4. Analysis of Trends 4.1 Employment Land Take-Up and Market Activity 16 4.2 Office Space – Market Activity 16 4.3 Industrial Space – Market Activity 17 4.4 Trends in Employment Land 18 Appendix 1 Glossary of Terms Appendix 2 Employment Land Supply in Aberdeen and map of Aberdeen City Industrial Estates Appendix 3 Employment Land Supply in Aberdeenshire Appendix 4 Aberdeenshire: Strategic Growth Areas and Regeneration Priority Areas Appendix 5 Historical Development Rates in Aberdeen City & Aberdeenshire and detailed description of 2018/19 completions December 2019 Aberdeen City Council Aberdeenshire Council Strategic Place Planning Planning and Environment Marischal College Service Broad Street Woodhill House Aberdeen Westburn Road AB10 1AB Aberdeen AB16 5GB Aberdeen City and Shire Strategic Development Planning Authority (SDPA) Woodhill House Westburn Road Aberdeen AB16 5GB Executive Summary Purpose and Background The Aberdeen City and Shire Employment Land Audit provides up-to-date and accurate information on the supply and availability of employment land in the North-East of Scotland. -

University of Aberdeen, Aberdeen, Scotland

UNIVERSITY OF WISCONSIN EAU CLAIRE ENTER FOR NTERNATIONAL DUCATION C I E Study Abroad UNIVERSITY OF ABERDEEN, ABERDEEN, SCOTLAND 2020 Program Guide ABLE OF ONTENTS Sexual Harassment and “Lad Culture” in the T C UK ...................................................................... 12 Academics .............................................................. 5 Emergency Contacts ...................................... 13 Pre-departure Planning .................................... 5 911 Equivalent in the UK ................................ 13 Graduate Courses ............................................. 5 Marijuana and other Illegal Drugs ................. 13 Credits and Course Load ................................. 5 Required Documents .......................................... 13 Registration at Aberdeen .................................. 5 Visa ................................................................... 13 Class Attendance .............................................. 5 Why Can’t I fly through Ireland? .................... 14 Grades ................................................................ 5 Visas for Travel to Other Countries .............. 14 Aberdeen & UWEC Transcripts ....................... 6 Packing Tips ........................................................ 14 UK Academic System ....................................... 6 Weather ............................................................ 14 Service-Learning ............................................... 8 Clothing ............................................................ -

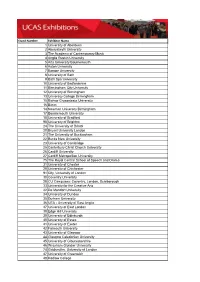

Stand Number Exhibitor Name 1 University of Aberdeen 2

Stand Number Exhibitor Name 1 University of Aberdeen 2 Aberystwyth University 3 The Academy of Contemporary Music 4 Anglia Ruskin University 5 Arts University Bournemouth 6 Aston University 7 Bangor University 8 University of Bath 9 Bath Spa University 10 University of Bedfordshire 11 Birmingham City University 12 University of Birmingham 13 University College Birmingham 15 Bishop Grosseteste University 16 Bimm 14 Newman University Birmingham 17 Bournemouth University 18 University of Bradford 98 University of Brighton 24 The University of Bristol 20 Brunel University London 21 The University of Buckingham 22 Bucks New University 23 University of Cambridge 25 Canterbury Christ Church University 26 Cardiff University 27 Cardiff Metropolitan University 75 The Royal Central School of Speech and Drama 31 University of Chester 29 University of Chichester 91 City, University of London 30 Coventry University 28 CU Campuses: Coventry, London, Scarborough 33 University for the Creative Arts 32 De Montfort University 34 University of Dundee 35 Durham University 36 UEA - University of East Anglia 37 University of East London 38 Edge Hill University 39 University of Edinburgh 40 University of Essex 41 University of Exeter 42 Falmouth University 43 University of Glasgow 44 Glasgow Caledonian University 45 University of Gloucestershire 46 Wrexham Glyndwr University 74 Goldsmiths, University of London 47 University of Greenwich 48 Hadlow College 49 Harper Adams University 50 Hartpury College and University Centre 51 Heriot-Watt University 52 University -

Discovery Research Portal

University of Dundee Novel biomarkers for risk stratification of Barrett's oesophagus associated neoplastic progression-epithelial HMGB1 expression and stromal lymphocytic phenotype Porter, Ross J.; Murray, Graeme I.; Brice, Daniel P.; Petty, Russell D.; McLean, Mairi H. Published in: British Journal of Cancer DOI: 10.1038/s41416-019-0685-1 Publication date: 2020 Document Version Peer reviewed version Link to publication in Discovery Research Portal Citation for published version (APA): Porter, R. J., Murray, G. I., Brice, D. P., Petty, R. D., & McLean, M. H. (2020). Novel biomarkers for risk stratification of Barrett's oesophagus associated neoplastic progression-epithelial HMGB1 expression and stromal lymphocytic phenotype. British Journal of Cancer, 122(4), 545-554. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41416-019- 0685-1 General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in Discovery Research Portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from Discovery Research Portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain. • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal. Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, -

School of Dentistry

School of Dentistry http://dentistry.dundee.ac.uk/ Vacancy CLINICAL RESEARCH FELLOW/ HONORARY SPECIALTY REGISTRAR in RESTORATIVE DENTISTRY NIHR HTA SCRIPT & PIP Trials Full Time Salary scale - £35,958 to £53,280 Informal enquiries are welcomed and intending applicants who would like to discuss the post further should contact Professor Jan Clarkson, [email protected], Professor David Ricketts [email protected] Dr Pauline Maillou(TPD) [email protected] Successful applicants will be subject to health clearance and the appropriate disclosure checks across the UK. Interviews will be held on: TBC Closing date: TBC The University of Dundee is committed to equal opportunities and welcomes applications from all sections of the community. School of Dentistry University of Dundee Level 9, Dundee Dental School Park Place Dundee, Scotland DD1 4HN http://dentistry.dundee.ac.uk/ Further Particulars 1. Job Title and Reporting Job Title: Clinical Research Fellow/Honorary Specialty Registrar in Restorative Dentistry Reporting to: Professor Jan Clarkson, Co-Chief Investigator, SCRIPT & PIP and TPD Staff Responsible for: n/a Duration of employment: Funded for up to 8 years 2. Job Purpose There are two elements to this post: Academic training by supporting the National Institute for Health Research’s HTA Programme SCRIPT Trial (17/127/07) and the PIP Trial (12/923/30) and completing a higher research degree Specialty training in Restorative Dentistry This is an exciting opportunity for qualified dentists looking for a stimulating -

University Museums and Collections Journal 7, 2014

VOLUME 7 2014 UNIVERSITY MUSEUMS AND COLLECTIONS JOURNAL 2 — VOLUME 7 2014 UNIVERSITY MUSEUMS AND COLLECTIONS JOURNAL VOLUME 7 20162014 UNIVERSITY MUSEUMS AND COLLECTIONS JOURNAL 3 — VOLUME 7 2014 UNIVERSITY MUSEUMS AND COLLECTIONS JOURNAL The University Museums and Collections Journal (UMACJ) is a peer-reviewed, on-line journal for the proceedings of the International Committee for University Museums and Collections (UMAC), a Committee of the International Council of Museums (ICOM). Editors Nathalie Nyst Réseau des Musées de l’ULB Université Libre de Bruxelles – CP 103 Avenue F.D. Roosevelt, 50 1050 Brussels Belgium Barbara Rothermel Daura Gallery - Lynchburg College 1501 Lakeside Dr., Lynchburg, VA 24501 - USA Peter Stanbury Australian Society of Anaesthetis Suite 603, Eastpoint Tower 180 Ocean Street Edgecliff, NSW 2027 Australia Copyright © International ICOM Committee for University Museums and Collections http://umac.icom.museum ISSN 2071-7229 Each paper reflects the author’s view. 4 — VOLUME 7 2014 UNIVERSITY MUSEUMS AND COLLECTIONS JOURNAL Basket porcelain with truss imitating natural fibers, belonged to a family in São Paulo, c. 1960 - Photograph José Rosael – Collection of the Museu Paulista da Universidade de São Paulo/Brazil Napkin holder in the shape of typical women from Bahia, painted wood, 1950 – Photograph José Rosael Collection of the Museu Paulista da Universidade de São Paulo/Brazil Since 1990, the Paulista Museum of the University of São Paulo has strived to form collections from the research lines derived from the history of material culture of the Brazilian society. This focus seeks to understand the material dimension of social life to define the particularities of objects in the viability of social and symbolic practices. -

George Murray, Then Schoolmaster at Downiehill

500 THE BARDS OF BON-ACCORD. 11840-1850. not been so heavily liandicapped in the struggle for existence. As we have just said, such speculations and regrets are useless, for, had Peter Still been in any other circumstances than in the poverty which he ennobled, it is doubtful if we would have had the pleasure of writing this sketch. The hard lot, natural thouoh it be to regret it, made the man what he was; a smoother path of life might have given us a conventional respectability, but it would not have given us the Peter Still of whom Buchan men and women may justly be proud. GEOEGE MUEEAY (JAMES BOLIVAE MANSON). We have seen how, \vhen Peter Still, early in 1839, first enter- tained the idea of putting his poetical wares into book form, one of his most enthusiastic advisers to print was a man of kindred tastes to himself, George Murray, then schoolmaster at Downiehill. Peter, though just recovering from a spell of ill-health, set out for the dominie's with a bundle of manuscript poems for his perusal and judgment, and he records in a letter to a friend how proud he returned home with Murray's favourable opinioji of his poems and intended scheme—yea, he had actually got 13 sheets of goodly foolscap writing paper from his adviser for a copy of " The Rocky Hill "—a stroke of business which came as a god-send to Peter in those days! George Murray was the son of a small crofter at Kinnoir, Huntly, and was born in 1819. -

Aberdeen's 'Toun College': Marischal College, 1593- 1623

Reid, S.J. (2007) Aberdeen's 'Toun College': Marischal College, 1593- 1623. Innes Review, 58 (2). pp. 173-195. ISSN 0020-157X http://eprints.gla.ac.uk/8119/ Deposited on: 06 November 2009 Enlighten – Research publications by members of the University of Glasgow http://eprints.gla.ac.uk The Innes Review vol. 58 no. 2 (Autumn 2007) 173–195 DOI: 10.3366/E0020157X07000054 Steven John Reid Aberdeen’s ‘Toun College’: Marischal College, 1593–1623 Introduction While debate has arisen in the past two decades regarding the foundation of Edinburgh University, by contrast the foundation and early development of Marischal College, Aberdeen, has received little attention. This is particularly surprising when one considers it is perhaps the closest Scottish parallel to the Edinburgh foundation. Founded in April 1593 by George Keith, fifth Earl Marischal in the burgh of New Aberdeen ‘to do the utmost good to the Church, the Country and the Commonwealth’,1 like Edinburgh Marischal was a new type of institution that had more in common with the Protestant ‘arts colleges’ springing up across the continent than with the papally sanctioned Scottish universities of St Andrews, Glasgow and King’s College in Old Aberdeen.2 James Kirk is the most recent in a long line of historians to argue that the impetus for founding ‘ane college of theologe’ in Edinburgh in 1579 was carried forward by the radical presbyterian James Lawson, which led to the eventual opening on 14 October 1583 of a liberal arts college in the burgh, as part of an educational reform programme devised and rolled out across the Scottish universities by the divine and educational reformer, Andrew Melville.3 However, in a self-professedly revisionist article Michael Lynch has argued that the college settlement was far more protracted and contingent on burgh politics than the simple insertion of a one-size 1 Fasti Academiae Mariscallanae Aberdonensis: Selections from the Records of the Marischal College and University, MDXCIII–MDCCCLX, ed. -

Library Guide

Library guide University staff resources in Special Collections Andrew MacGregor, May 2018 QG HCOL037 [https://www.abdn.ac.uk/special-collections/documents/guides/qghcol037.pdf] The Wolfson Reading Room King’s College and Marischal Special Collections Centre College (1495 – 1860) The University Library King's College University of Aberdeen Bedford Road Officers and graduates of University and Aberdeen King's College Aberdeen MVD-MDCCCLX AB24 3AA (ed. P.J. Anderson, Aberdeen: New Spalding Club, 1893) - includes: Tel. (01224)272598 List of staff, containing biographical information, E–mail: [email protected] position held, date of appointment, previous Website: www.abdn.ac.uk/library/about/special/ classes taught and publications (pages 3 – 94). A table illustrating the date sequence Introduction of regents (pages 313 – 323). The great majority of family historians who contact Marischal College us do so because their ancestor may have attended Fasti Academiae Mariscallanae Aberdonensis: and/or worked at the University. selections from the records of the Marischal A brief note on the University’s history may help College and University MDXCIII-MDCCCLX direct research in the first instance. The University (ed. P. J. Anderson, Aberdeen: Spalding Club, of Aberdeen was a creation of the union of King's 1898). Volume 2 includes: College (founded in 1495) and Marischal College List of staff, containing biographical information, (founded in 1593). These two institutions joined position held, date of appointment, previous together in the fusion of 1860 to become the classes taught and publications (pages 3 – 77). University of Aberdeen. A table illustrating the date sequence of regents As well as the University’s own records there are (pages 587 – 595).