Early Women Engineering Graduates from Scottish Universities

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Obituary Peter Payne 2017

Professor Peter Payne It is with great sadness that Council reports the death of our distinguished and long serving President, Professor Peter Payne. Peter died on 10 January 2017, aged 87 years. A well attended service of committal was held at Aberdeen Crematorium on 20 th January, allowing many friends and colleagues to offer their condolences to Enid and their son and daughter, Simon and Samantha. They each contributed moving and frequently amusing recollections of their father, sympathetically read by the minister, Deaconess Marion Stewart. Peter was a Londoner whose academic path took him to Nottingham University where, in 1951, he graduated in the new and minority discipline of Economic History. His mentor was Professor David Chambers, who then set Peter on his research for his PhD, gained in 1954, and later published in 1961 as Rubber and Railways in the Nineteenth Century; A Study of the Spencer Papers, 1853 – 1891 . He had begun as he was to continue in his career, his scholarship founded on expert analysis of business records, and demonstrating their significance in understanding wider issues of economic and social development. His successful PhD launched him into two years of research at Johns Hopkins, this producing in 1956 a fine detailed study of The Savings Bank of Baltimore, 1818 – 1866 co-authored with Lance Davis. This was a spectacular start to an academic career in the new and relatively small discipline of Economic History, but building it had to wait, as National Service drew Peter into two years in the Royal Army Educational Corps. There he had the unusual experience of serving for a time on the staff of a military detention barracks. -

Women in the Maritime Industry

World Maritime University The Maritime Commons: Digital Repository of the World Maritime University World Maritime University Dissertations Dissertations 2000 Women in the maritime industry : a review of female participation and their role in Maritime Education and Training in the 21st century Hannah Aba Aggrey World Maritime University Follow this and additional works at: http://commons.wmu.se/all_dissertations Part of the Gender and Sexuality Commons Recommended Citation Aggrey, Hannah Aba, "Women in the maritime industry : a review of female participation and their role in Maritime Education and Training in the 21st century" (2000). World Maritime University Dissertations. 383. http://commons.wmu.se/all_dissertations/383 This Dissertation is brought to you courtesy of Maritime Commons. Open Access items may be downloaded for non-commercial, fair use academic purposes. No items may be hosted on another server or web site without express written permission from the World Maritime University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WORLD MARITIME UNIVERSITY Malmö, Sweden WOMEN IN THE MARITIME INDUSTRY: A review of female participation, and their role in Maritime Education and Training (MET) in the 21st Century By HANNAH ABA AGGREY Ghana A dissertation submitted to the World Maritime University in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the award of the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE in MARITIME EDUCATION AND TRAINING (Nautical) 2000 Copyright Hannah Aba Aggrey, 2000 DECLARATION I certify that all the material in this dissertation that is not my own work has been identified, and that no material is included for which a degree has previously been conferred on me. The contents of this dissertation reflect my own personal views, and are not necessarily endorsed by the University. -

THE UNIVERSITY of ABERDEEN and the ROBERT GORDON UNIVERSITY MILITARY EDUCATION COMMITTEE

THE UNIVERSITY OF ABERDEEN and THE ROBERT GORDON UNIVERSITY MILITARY EDUCATION COMMITTEE Minutes of the Meeting held in the University of Aberdeen on 7 December 2009 Present: Professor T Salmon (Convener), Professor D Alexander, Squadron Leader K Block (representing Squadron Leader Gusterson), Professor J Broom, Ms C Buchanan, Dr A Clarke, Professor R Flin, Dr D Galbreath, Dr J Grieve, Wing Commander M Henderson, Lieutenant M Hutchinson, Mr J Lemon, Chief Petty Officer Mitchell, Professor P Robertson, Lieutenant Colonel K Wardner; with Ms Y Gordon (Clerk) Apologies: Principals Rice and Pittilo, Brigadier H Allfrey, Mr P Fantom, Wing Commander Kennedy and Lieutenant A Rose. The Convener invited members to introduce themselves and welcomed the following members who were attending for the first time: Professor Broom, Lieutenant Colonel Wardner, Lieutenant Hutchinson. He went on to inform the Committee of the sad news that Dr Molyneaux had passed away in the Spring. The Convener also thanked the former Clerk to the Committee, Mr Duggan, who had served as Clerk for many years. FOR DISCUSSION 1. Minutes The Committee approved the Minutes of the Meeting held on 1 December 2008 (copy filed as MEC09/1) 2. Unit Progress Reports URNU 2.1 The Committee considered a report from the Universities Royal Naval Unit, January – December 2009. (copy filed as MEC09/2a) 2.2 Lieutenant Hutchinson reported that 29 new students had been recruited, with a good cohort of 25 remaining. Unit strength currently stood at 51, at full capacity, and was split 24 male to 27 female. The Unit’s summer deployment of eight weeks duration was in the South H:\My documents\Policy Zone\Committe Minutes\Military Education1 Committee\Minutes7Dec09.doc Coast of England and included a visit to Greenwich and London. -

Memory for Emotional Faces in Major Depression 1

Memory for emotional faces in major depression 1 Running title: MEMORY FOR EMOTIONAL FACES IN MAJOR DEPRESSION Word Count: 4251 (excluding the abstract, references and tables) Memory for emotional faces in major depression following judgement of physical facial characteristics at encoding Nathan Ridout Aston University, Birmingham, UK Barbara Dritschel University of St Andrews, UK Keith Matthews and Maureen McVicar University of Dundee, UK Ian C. Reid University of Aberdeen, UK Ronan E. O’ Carroll University of Stirling, UK Address for correspondence: Dr Nathan Ridout Clinical and Cognitive Neurosciences Research Group School of Life and Health Sciences Aston University Birmingham, B7 4ET Tel: (+44 121) 2044162 Fax: (+44 121) 2044090 Email: [email protected] Memory for emotional faces in major depression 2 Abstract The aim of the present study was to establish if patients with major depression (MD) exhibit a memory bias for sad faces, relative to happy and neutral, when the affective element of the faces is not explicitly processed at encoding. To this end, 16 psychiatric outpatients with MD and 18 healthy, never-depressed controls (HC) were presented with a series of emotional faces and were required to identify the gender of the individuals featured in the photographs. Participants were subsequently given a recognition memory test for these faces. At encoding, patients with MD exhibited a non-significant tendency towards slower gender identification (GI) times, relative to HC, for happy faces. However, the GI times of the two groups did not differ for sad or neutral faces. At memory testing, patients with MD did not exhibit the expected memory bias for sad faces. -

Born with a Silver Spanner in Her Hand

COLUMN REFRIGERATION APPLICATIONS This article was published in ASHRAE Journal, December 2018. Copyright 2018 ASHRAE. Reprinted here by permission from ASHRAE at www. star-ref.co.uk. This article may not be copied nor distributed in either paper or digital form by other parties without ASHRAE’s permission. For more information about ASHRAE, visit www.ashrae.org. Andy Pearson Born With a Silver Spanner in Her Hand BY ANDY PEARSON, PH.D., C.ENG., FELLOW ASHRAE I’m writing this column on the birthday of one of the most unusual and inspiring characters in engineering history. She was born in a Scottish castle near Perth into a family of the landed gentry and was named after her godmother who was Queen of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. Despite her noble beginnings Victoria Drummond clearly had an aptitude for hands-on engineering. As a young girl she enjoyed making wooden toys and mod- els and is said to have won prizes for them. Aged 21 she started an apprenticeship in a garage in Perth and two years later transferred her training to the Caledon Shipbuilding yard in Dundee, where she served her time in the pattern shop for the foundry and in the fin- ishing shop. After two more years she completed her apprenticeship and spent further time as a journey- man engine builder and then in the drawing office at Caledon. When the yard hit hard times a couple of years later she was laid off, but managed to get a place with the Blue Funnel line in Liverpool and after a short trial voyage she was signed on as tenth engineer (the bottom rung of the ladder) on a passenger liner sailing between England and Australia. -

University of Aberdeen, Aberdeen, Scotland

UNIVERSITY OF WISCONSIN EAU CLAIRE ENTER FOR NTERNATIONAL DUCATION C I E Study Abroad UNIVERSITY OF ABERDEEN, ABERDEEN, SCOTLAND 2020 Program Guide ABLE OF ONTENTS Sexual Harassment and “Lad Culture” in the T C UK ...................................................................... 12 Academics .............................................................. 5 Emergency Contacts ...................................... 13 Pre-departure Planning .................................... 5 911 Equivalent in the UK ................................ 13 Graduate Courses ............................................. 5 Marijuana and other Illegal Drugs ................. 13 Credits and Course Load ................................. 5 Required Documents .......................................... 13 Registration at Aberdeen .................................. 5 Visa ................................................................... 13 Class Attendance .............................................. 5 Why Can’t I fly through Ireland? .................... 14 Grades ................................................................ 5 Visas for Travel to Other Countries .............. 14 Aberdeen & UWEC Transcripts ....................... 6 Packing Tips ........................................................ 14 UK Academic System ....................................... 6 Weather ............................................................ 14 Service-Learning ............................................... 8 Clothing ............................................................ -

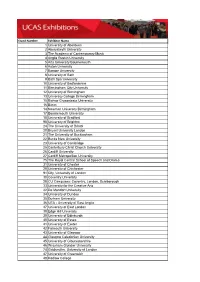

Stand Number Exhibitor Name 1 University of Aberdeen 2

Stand Number Exhibitor Name 1 University of Aberdeen 2 Aberystwyth University 3 The Academy of Contemporary Music 4 Anglia Ruskin University 5 Arts University Bournemouth 6 Aston University 7 Bangor University 8 University of Bath 9 Bath Spa University 10 University of Bedfordshire 11 Birmingham City University 12 University of Birmingham 13 University College Birmingham 15 Bishop Grosseteste University 16 Bimm 14 Newman University Birmingham 17 Bournemouth University 18 University of Bradford 98 University of Brighton 24 The University of Bristol 20 Brunel University London 21 The University of Buckingham 22 Bucks New University 23 University of Cambridge 25 Canterbury Christ Church University 26 Cardiff University 27 Cardiff Metropolitan University 75 The Royal Central School of Speech and Drama 31 University of Chester 29 University of Chichester 91 City, University of London 30 Coventry University 28 CU Campuses: Coventry, London, Scarborough 33 University for the Creative Arts 32 De Montfort University 34 University of Dundee 35 Durham University 36 UEA - University of East Anglia 37 University of East London 38 Edge Hill University 39 University of Edinburgh 40 University of Essex 41 University of Exeter 42 Falmouth University 43 University of Glasgow 44 Glasgow Caledonian University 45 University of Gloucestershire 46 Wrexham Glyndwr University 74 Goldsmiths, University of London 47 University of Greenwich 48 Hadlow College 49 Harper Adams University 50 Hartpury College and University Centre 51 Heriot-Watt University 52 University -

Discovery Research Portal

University of Dundee Novel biomarkers for risk stratification of Barrett's oesophagus associated neoplastic progression-epithelial HMGB1 expression and stromal lymphocytic phenotype Porter, Ross J.; Murray, Graeme I.; Brice, Daniel P.; Petty, Russell D.; McLean, Mairi H. Published in: British Journal of Cancer DOI: 10.1038/s41416-019-0685-1 Publication date: 2020 Document Version Peer reviewed version Link to publication in Discovery Research Portal Citation for published version (APA): Porter, R. J., Murray, G. I., Brice, D. P., Petty, R. D., & McLean, M. H. (2020). Novel biomarkers for risk stratification of Barrett's oesophagus associated neoplastic progression-epithelial HMGB1 expression and stromal lymphocytic phenotype. British Journal of Cancer, 122(4), 545-554. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41416-019- 0685-1 General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in Discovery Research Portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from Discovery Research Portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain. • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal. Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, -

School of Dentistry

School of Dentistry http://dentistry.dundee.ac.uk/ Vacancy CLINICAL RESEARCH FELLOW/ HONORARY SPECIALTY REGISTRAR in RESTORATIVE DENTISTRY NIHR HTA SCRIPT & PIP Trials Full Time Salary scale - £35,958 to £53,280 Informal enquiries are welcomed and intending applicants who would like to discuss the post further should contact Professor Jan Clarkson, [email protected], Professor David Ricketts [email protected] Dr Pauline Maillou(TPD) [email protected] Successful applicants will be subject to health clearance and the appropriate disclosure checks across the UK. Interviews will be held on: TBC Closing date: TBC The University of Dundee is committed to equal opportunities and welcomes applications from all sections of the community. School of Dentistry University of Dundee Level 9, Dundee Dental School Park Place Dundee, Scotland DD1 4HN http://dentistry.dundee.ac.uk/ Further Particulars 1. Job Title and Reporting Job Title: Clinical Research Fellow/Honorary Specialty Registrar in Restorative Dentistry Reporting to: Professor Jan Clarkson, Co-Chief Investigator, SCRIPT & PIP and TPD Staff Responsible for: n/a Duration of employment: Funded for up to 8 years 2. Job Purpose There are two elements to this post: Academic training by supporting the National Institute for Health Research’s HTA Programme SCRIPT Trial (17/127/07) and the PIP Trial (12/923/30) and completing a higher research degree Specialty training in Restorative Dentistry This is an exciting opportunity for qualified dentists looking for a stimulating -

Public Financing of Health Care in Eight Western Countries

PUBLIC FINANCING OF HEALTH CARE IN EIGHT WESTERN COUNTRIES The Introduction of Universal Coverage BY ALEXANDER SHALOM PREKER Ph.D. Thesis Submitted to Fulfill Requirements for a Degree of Doctor of Philosophy at the London School of Economics and Political Science UMI Number: U048587 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U048587 Published by ProQuest LLC 2014. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 rnsse F 686 X c2I ABSTRACT The public sector of all western developed countries has become increasingly involved in financing health care during the past century. Today, thirteen OECD countries have passed landmark legislative reforms that call for compulsory prepayment and universal entitlement to comprehensive services, while most of the others achieve similar coverage through a mixture of public and private voluntary arrangements. This study carried out a detailed analysis of why, how and to what effect governments became involved in health care financing in eight of these countries. During the early phase of this evolution, reliance on direct out-of-pocket payment and an unregulated market mechanism for the financing, production and delivery of health care led to many unsatisfactory outcomes in the allocation of scarce resources, redistribution of the financial burden of illness and stabilisation of health care activities. -

Agenda Frontsheet PDF 133 KB

COURT OF ALDERMEN SIR/MADAM YOUR Worship is desired to be at a Court of Aldermen, in the Aldermen’s Court Room, on Tuesday next, the 3rd day of JULY, 2018. The Lord Mayor will take the Chair at 12.30 pm of the clock in the afternoon precisely. (if unable to attend please inform the Town Clerk at once.) TIM ROLPH, Swordbearer. Swordbearer’s Office, Mansion House, Tuesday, 26th June 2018 1 Question- That the minutes of the last Court are correctly recorded? 2 Resignations, Retirements and Memorials etc. 3 The Chamberlain's list of applicants for Freedom of the City:- Name Occupation Address Company Martyn Stuart Cozens a Sales Director Nantyderry, Brewers Abergavenny, Monmouthshire Richard William Stewart a Royal Air Force Howden, Goole, Air Pilots Reservist Yorkshire Louise Margaret Kiely a Facilities Consultant Rodington, Shropshire Pattenmakers Matthew William Willson a Brewer West Bridgford, Brewers Nottinghamshire, Paul Graham Wilkinson The City Surveyor North Wootton, King's Carpenters Lynn, Norfolk Emily Margaret Clare a Project Manager Battersea Girdlers Choynowski Stephen James Mayhew a Management Consultant Bath, Somerset Management Consultants 2 Name Occupation Address Company Air Marshal Julian a Royal Air Force Officer Bath Engineers Alexander Young, CB, OBE Claire Sarah Barrett an Embroidery Company Islington Broderers Director Thomas Leonard Howard an Expert Clapham Arbitrators Walford Witness/arbitrator Alban Francis Xavier a National Shoreham-by-Sea, West Stationers & Green, CBE SchoolsCommissioner, Sussex Newspaper Makers -

Effectiveness of First Dose of COVID-19 Vaccines Against Hospital Admissions in Scotland: National Prospective Cohort Study of 5.4 Million People

This is a preprint and has not yet been peer reviewed Effectiveness of first dose of COVID-19 vaccines against hospital admissions in Scotland: national prospective cohort study of 5.4 million people Dr Eleftheria Vasileiou PhD, Usher Institute, The University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, EH8 9AG, UK, [email protected], Tel: 077 3296 1139 (Corresponding author)* Professor Colin R Simpson PhD, School of Health, Wellington Faculty of Health, Victoria University of Wellington, NZ and Usher Institute, University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, UK* Professor Chris Robertson PhD, Department of Mathematics and Statistics, University of Strathclyde, Glasgow, UK and Public Health Scotland, Glasgow, UK* Dr Ting Shi PhD, Usher Institute, The University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, UK* Dr Steven Kerr PhD, Usher Institute, The University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, EH8 9AG, UK* Dr Utkarsh Agrawal PhD, School of Medicine, University of St. Andrews, St Andrews, UK Mr Ashley Akbari, Population Data Science MSc, Swansea University Medical School, Swansea, UK Dr Stuart Bedston PhD, Population Data Science, Swansea University Medical School, UK Mrs Jillian Beggs, PPIE Lead, BREATHE – The Health Data Research Hub for Respiratory Health, UK Dr Declan Bradley MD, Queen’s University Belfast / Public Health Agency Mr Antony Chuter FRCGP (Hon) Lay member, Usher Institute, The University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, UK Prof Simon de Lusignan MD, Nuffield Dept Primary Care Health Sciences, University of Oxford, UK Dr Annemarie B Docherty PhD, Usher Institute, The University