Download This PDF File

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Transcultural Perspective on the Casting of the Rose Tattoo

RSA JOU R N A L 25/2014 GIULIANA MUS C IO A Transcultural Perspective on the Casting of The Rose Tattoo A transcultural perspective on the film The Rose Tattoo (Daniel Mann, 1955), written by Tennessee Williams, is motivated by its setting in an Italian-American community (specifically Sicilian) in Louisiana, and by its cast, which includes relevant Italian participation. A re-examination of its production and textuality illuminates not only Williams’ work but also the cultural interactions between Italy and the U.S. On the background, the popularity and critical appreciation of neorealist cinema.1 The production of the film The Rose Tattoo has a complicated history, which is worth recalling, in order to capture its peculiar transcultural implications in Williams’ own work, moving from some biographical elements. In the late 1940s Tennessee Williams was often traveling in Italy, and visited Sicily, invited by Luchino Visconti (who had directed The Glass Managerie in Rome, in 1946) for the shooting of La terra trema (1948), where he went with his partner Frank Merlo, an occasional actor of Sicilian origins (Williams, Notebooks 472). Thus his Italian experiences involved both his professional life, putting him in touch with the lively world of Italian postwar theater and film, and his affections, with new encounters and new friends. In the early 1950s Williams wrote The Rose Tattoo as a play for Anna Magnani, protagonist of the neorealist masterpiece Rome Open City (Roberto Rossellini, 1945). However, the Italian actress was not yet comfortable with acting in English and therefore the American stage version (1951) starred Maureen Stapleton instead and Method actor Eli Wallach. -

Anniversary Season

th ASOLO REPERTORY THEATRE o ANNIVERSARY6 SEASON ASOLO REPERTORY THEATRE th 6oANNIVERSARY DINNER November 26, 2018 The Westin | Sarasota 6pm | Cocktail Reception 7pm | Dinner, Presentation and Award Ceremony • Vic Meyrich Tech Award • Bradford Wallace Acting Award 03 HONOREES Honoring 12 artists who made an indelible impact on the first decade and beyond. 04-05 WELCOME LETTER 06-11 60 YEARS OF HISTORY 12-23 HONOREE INTERVIEWS 24-27 LIST OF PRODUCTIONS From 1959 through today rep 31 TRIBUTES o l aso HONOREES Steve Hogan Assistant Technical Director, 1969-1982 Master Carpenter, 1982-2001 Shop Foreman, 2001-Present Polly Holliday Resident Acting Company, 1962-1972 Vic Meyrich Technical Director, 1968-1992 Production Manager, 1992-2017 Production Manager & Operations Director, 2017-Present Howard Millman Actor, 1959 Managing Director, Stage Director, 1968-1980 Producing Artistic Director, 1995-2006 Stephanie Moss Resident Acting Company, 1969-1970 Assistant Stage Manager, 1972-1990 Bob Naismith Property Master, 1967-2000 Barbara Redmond Resident Acting Company, 1968-2011 Director, Playwright, 1996-2003 Acting Faculty/Head of Acting, FSU/Asolo Conservatory, 1998-2011 Sharon Spelman Resident Acting Company, 1968-1971 and 1996-2010 Eberle Thomas Director, Actor, Playwright, 1960-1966 rep Co-Artistic Director, 1966-1973 Director, Actor, Playwright, 1976-2007 Brad Wallace o Resident Acting Company, 1961-2008 l Marian Wallace Box Office Associate, 1967-1968 Stage Manager, 1968-1969 Production Stage Manager, 1969-2010 John M. Wilson Master Carpenter, 1969-1977 asolorep.org | 03 aso We are grateful you are here tonight to celebrate and support Asolo Rep — MDE/LDG PHOTO WHICH ONE ??? Nationally renowned, world-class theatre, made in Sarasota. -

William and Mary Theatre Main Stage Productions

WILLIAM AND MARY THEATRE MAIN STAGE PRODUCTIONS 1926-1927 1934-1935 1941-1942 The Goose Hangs High The Ghosts of Windsor Park Gas Light Arms and the Man Family Portrait 1927-1928 The Romantic Age The School for Husbands You and I The Jealous Wife Hedda Gabler Outward Bound 1935-1936 1942-1943 1928-1929 The Unattainable Thunder Rock The Enemy The Lying Valet The Male Animal The Taming of the Shrew The Cradle Song *Bach to Methuselah, Part I Candida Twelfth Night *Man of Destiny Squaring the Circle 1929-1930 1936-1937 The Mollusc Squaring the Circle 1943-1944 Anna Christie Death Takes a Holiday Papa is All Twelfth Night The Gondoliers The Patriots The Royal Family A Trip to Scarborough Tartuffe Noah Candida 1930-1931 Vergilian Pageant 1937-1938 1944-1945 The Importance of Being Earnest The Night of January Sixteenth Quality Street Just Suppose First Lady Juno and the Paycock The Merchant of Venice The Mikado Volpone Enter Madame Liliom Private Lives 1931-1932 1938-1939 1945-1946 Sun-Up Post Road Pygmalion Berkeley Square RUR Murder in the Cathedral John Ferguson The Pirates of Penzance Ladies in Retirement As You Like It Dear Brutus Too Many Husbands 1932-1933 1939-1940 1946-1947 Outward Bound The Inspector General Arsenic and Old Lace Holiday Kind Lady Arms and the Man The Recruiting Officer Our Town The Comedy of Errors Much Ado About Nothing Hay Fever Joan of Lorraine 1933-1934 1940-1941 1947-1948 Quality Street You Can’t Take It with You The Skin of Our Teeth Hotel Universe Night Must Fall Blithe Spirit The Swan Mary of Scotland MacBeth -

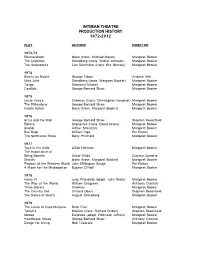

History of Intiman

INTIMAN THEATRE PRODUCTION HISTORY 1972-2012 PLAY AUTHOR DIRECTOR 1972-73 Rosmersholm Ibsen (trans. Michael Meyer) Margaret Booker The Creditors Strindberg (trans. Walter Johnson) Margaret Booker The Underpants Carl Sternheim (trans. Eric Bentley) Margaret Booker 1974 Brecht on Brecht George Tabori Andrew Witt Miss Julie Strindberg (trans. Margaret Booker) Margaret Booker Tango Slaw omir Mrozek Margaret Booker Candida George Bernard Shaw Margaret Booker 1975 Uncle Vanya Chekhov (trans. Christopher Hampton) Margaret Booker The Philanderer George Bernard Shaw Margaret Booker Hedda Gabler Ibsen (trans. Margaret Booker) Margaret Booker 1976 Arms and the Man George Bernard Shaw Stephen Rosenfield Elektra Sophocles (trans. David Grene) Margaret Booker Anatol Arthur Schnitzler Margaret Booker Bus Stop William Inge Pat Patton The Northw est Show Barry Pritchard Margaret Booker 1977 Toys in the Attic Lillian Hellman Margaret Booker The Importance of Being Earnest Oscar Wilde Clayton Corzatte Ghosts Ibsen (trans. Margaret Booker) Margaret Booker Playboy of the Western World John Millington Synge Pat Patton A Moon for the Misbegotten Eugene O' Neill Margaret Booker 1978 Henry IV Luigi Pirandello (adapt. John Reich) Margaret Booker The Way of the World William Congreve Anthony Cornish Three Sisters Chekhov Margaret Booker The Country Girl Clifford Odets Stephen Rosenfield The Dance of Death August Strindberg Margaret Booker 1979 The Loves of Cass McGuire Brian Friel Margaret Booker Tartuffe Molière (trans. Richard Wilbur) Stephen Rosenfield Medea Euripides (adapt. Robinson Jeffers) Margaret Booker Heartbreak House George Bernard Shaw Anthony Cornish Design for Living Noë l Cow ard Margaret Booker 1980 Othello William Shakespeare Margaret Booker The Lady's Not for Burning Christopher Fry William Glover Leonce and Lena Georg Bü chner Margaret Booker (trans. -

Table of Contents

GEVA THEATRE CENTER PRODUCTION HISTORY TH 2012-2013 SEASON – 40 ANNIVERSARY SEASON Mainstage: You Can't Take it With You (Moss Hart and George S. Kaufman) Freud's Last Session (Mark St. Germain) A Christmas Carol (Charles Dickens; Adapted/Directed by Mark Cuddy/Music/Lyrics by Gregg Coffin) Next to Normal (Music by Tom Kitt, Book/Lyrics by Brian Yorkey) The Book Club Play (Karen Zacarias) The Whipping Man (Matthew Lopez) A Midsummer Night's Dream (William Shakespeare) Nextstage: 44 Plays For 44 Presidents (The Neofuturists) Sister’s Christmas Catechism (Entertainment Events) The Agony And The Ecstasy Of Steve Jobs (Mike Daisey) No Child (Nilaja Sun) BOB (Peter Sinn Nachtrieb, an Aurora Theatre Production) Venus in Fur (David Ives, a Southern Repertory Theatre Production) Readings and Festivals: The Hornets’ Nest Festival of New Theatre Plays in Progress Regional Writers Showcase Young Writers Showcase 2011-2012 SEASON Mainstage: On Golden Pond (Ernest Thompson) Dracula (Steven Dietz; Adapted from the novel by Bram Stoker) A Christmas Carol (Charles Dickens; Adapted/Directed by Mark Cuddy/Music/Lyrics by Gregg Coffin) Perfect Wedding (Robin Hawdon) A Raisin in the Sun (Lorraine Hansberry) Superior Donuts (Tracy Letts) Company (Book by George Furth, Music, & Lyrics by Stephen Sondheim) Nextstage: Late Night Catechism (Entertainment Events) I Got Sick Then I Got Better (Written and performed by Jenny Allen) Angels in America, Part One: Millennium Approaches (Tony Kushner, Method Machine, Producer) Voices of the Spirits in my Soul (Written and performed by Nora Cole) Two Jews Walk into a War… (Seth Rozin) Readings and Festivals: The Hornets’ Nest Festival of New Theatre Plays in Progress Regional Writers Showcase Young Writers Showcase 2010-2011 SEASON Mainstage: Amadeus (Peter Schaffer) Carry it On (Phillip Himberg & M. -

External Content.Pdf

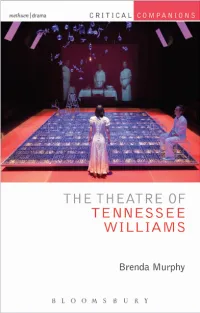

i THE THEATRE OF TENNESSEE WILLIAMS Brenda Murphy is Board of Trustees Distinguished Professor of English, Emeritus at the University of Connecticut. Among her 18 books on American drama and theatre are Tennessee Williams and Elia Kazan: A Collaboration in the Theatre (1992), Understanding David Mamet (2011), Congressional Theatre: Dramatizing McCarthyism on Stage, Film, and Television (1999), The Provincetown Players and the Culture of Modernity (2005), and as editor, Critical Insights: Tennessee Williams (2011) and Critical Insights: A Streetcar Named Desire (2010). In the same series from Bloomsbury Methuen Drama: THE PLAYS OF SAMUEL BECKETT by Katherine Weiss THE THEATRE OF MARTIN CRIMP (SECOND EDITION) by Aleks Sierz THE THEATRE OF BRIAN FRIEL by Christopher Murray THE THEATRE OF DAVID GREIG by Clare Wallace THE THEATRE AND FILMS OF MARTIN MCDONAGH by Patrick Lonergan MODERN ASIAN THEATRE AND PERFORMANCE 1900–2000 Kevin J. Wetmore and Siyuan Liu THE THEATRE OF SEAN O’CASEY by James Moran THE THEATRE OF HAROLD PINTER by Mark Taylor-Batty THE THEATRE OF TIMBERLAKE WERTENBAKER by Sophie Bush Forthcoming: THE THEATRE OF CARYL CHURCHILL by R. Darren Gobert THE THEATRE OF TENNESSEE WILLIAMS Brenda Murphy Series Editors: Patrick Lonergan and Erin Hurley LONDON • NEW DELHI • NEW YORK • SYDNEY Bloomsbury Methuen Drama An imprint of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc 50 Bedford Square 1385 Broadway London New York WC1B 3DP NY 10018 UK USA www.bloomsbury.com Bloomsbury is a registered trademark of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc First published 2014 © Brenda Murphy, 2014 This work is published subject to a Creative Commons Attribution Non-commercial No Derivatives Licence. You may share this work for non-commercial purposes only, provided you give attribution to the copyright holder and the publisher. -

William & Mary Theatre Main Stage Productions

WILLIAM & MARY THEATRE MAIN STAGE PRODUCTIONS 1926-1927 1934-1935 1941-1942 The Goose Hangs High The Ghosts of Windsor Park Gas Light Arms and the Man Family Portrait 1927-1928 The Romantic Age The School for Husbands You and I The Jealous Wife Hedda Gabler Outward Bound 1935-1936 1942-1943 1928-1929 The Unattainable Thunder Rock The Enemy The Lying Valet The Male Animal The Taming of the Shrew The Cradle Song *Bach to Methuselah, Part I Candida Twelfth Night *Man of Destiny Squaring the Circle 1929-1930 1936-1937 The Mollusc Squaring the Circle 1943-1944 Anna Christie Death Takes a Holiday Papa is All Twelfth Night The Gondoliers The Patriots The Royal Family A Trip to Scarborough Tartuffe Noah Candida 1930-1931 Vergilian Pageant 1937-1938 1944-1945 The Importance of Being Earnest The Night of January Sixteenth Quality Street Just Suppose First Lady Juno and the Paycock The Merchant of Venice The Mikado Volpone Enter Madame Liliom Private Lives 1931-1932 1938-1939 1945-1946 Sun-Up Post Road Pygmalion Berkeley Square RUR Murder in the Cathedral John Ferguson The Pirates of Penzance Ladies in Retirement As You Like It Dear Brutus Too Many Husbands 1932-1933 1939-1940 1946-1947 Outward Bound The Inspector General Arsenic and Old Lace Holiday Kind Lady Arms and the Man The Recruiting Officer Our Town The Comedy of Errors Much Ado About Nothing Hay Fever Joan of Lorraine 1933-1934 1940-1941 1947-1948 Quality Street You Can’t Take It with You The Skin of Our Teeth Hotel Universe Night Must Fall Blithe Spirit The Swan Mary of Scotland MacBeth -

Elizabeth Laidlaw

Elizabeth Laidlaw AEA, SAG, AFTRA, SAG/AFTRA FILM & TELEVISION NCIS Guest Star CBS Tony Wharmby The Red Line Series Regular CBS Various Chicago PD Guest Star NBC Mark Tinker The Haven (WebSeries) Series Regular The Haven Productions Various Henry Gamble's Birthday Party Supporting Cone Arts Stephen Cone Chicago PD Guest Star NBC Reza Tabrizi Crisis Recurring NBC Various Betrayal Guest Star ABC David Zabel Boss Recurring Starz Various The Chicago Code Guest Star FOX Michael Offer Into the Wake Supporting Diesel Bros. Films John Mossman Eastern College Supporting Lucky Penny Pictures James Flynn Dimension Supporting Rusted Rhino Productions Matthew Harris Three Days Supporting Poya Pictures Adrian Fulle Turks Guest Star CBS Robert Singer CHICAGO THEATRE The Man-Beast Virginie Allard First Folio Theatre Haley Rice Romeo and Juliet Prince Escalus/Apothecary Chicago Shakespeare Theatre Marti Lyons East of Eden Eva/Mrs. Bacon/Nurse Steppenwolf Theatre Terry Kinney Grounded The Pilot Northwestern/ETOPiA John Gawlik Lucinda's Bed Lucinda Chicago Dramatist's Workshop Jessi D. Hill The Maids Solange Writer's Theatre Jimmy McDermott The Two Noble Kingsmen Hippolyta Chicago Shakespeare Theatre Darko Treznijak Kabuki Lady Macbeth Witch (Lady Macbeth) Chicago Shakespeare Theatre Shozo Sato Omnium Gatherum Lydia The Next Theatre Jason Loewith As You Like It Rosalind Chicago Shakespeare Theatre David Bell Phèdre Enone Court Theatre JoAnne Akalaitis Life's a Dream Estrella Court Theatre JoAnne Akalaitis The Rose Tattoo Violetta Goodman Theatre Kate Whoriskey The Berlin Circle Christa Steppenwolf Theatre Tina Landau The Kentucky Cycle* Morning Star Pegasus Players Warner Crocker Angels in America** The Angel, etc. The Journeymen David Cromer REGIONAL THEATRE The Three Musketeers Milady DeWinter Indiana Repertory Theatre Henry Woronicz The Crucible Elizabeth Proctor Indiana Repertory Theatre Michael Edwards The Birthday Party Lulu American Repertory Theatre JoAnne Akalaitis Hamlet Hamlet R.A.D.A./London Nona Shepphard Mrs. -

Interchapter Ii: 1940–1969

INTERCHAPTER II: 1940–1969 Melissa Sihra Lady Augusta Gregory died in 1932 and from that period the Abbey Theatre consisted of an all-male directorate – Yeats, Kevin O’Higgins, Ernest Blythe, Brinsley MacNamara, Lennox Robinson and Walter Starkie. Blythe, an Irish-language revivalist and politician, would now remain on the inside of the Abbey for many years to come. Issues of artistic policy remained primarily within Yeats’s domain, but with his death in 1939 the position of power was open and Blythe took over as Managing Director in 1941, remaining in that post until 1967. Earnán de Blaghd, as he preferred to be known, espoused a conser- vative ethos and the board as a whole was highly restrictive artist- ically. While the work of a significant number of women dramat- ists was produced during these decades (see Appendix pp. 223–4), this period in the Abbey’s history is associated predominantly ‘with kitchen farce, unspeakably bad Gaelic pantomimes, compulsory Irish and insensitive bureaucracy’.1 The move from the 1930s into the 1940s saw the consolidation of Éamon De Valera’s Fianna Fáil administra- tion. Bunreacht na hÉireann (The Irish Constitution) was established in 1937, the same year that Samuel Beckett moved to Paris. During this time women activists sought political representation and equal rights as citizens of the Irish Free State, particularly with regard to the 1932 marriage bar. In 1938 Hannah Sheehy-Skeffington, a prolific feminist campaigner and member of the Women’s Graduates’ Associ- ation, argued that the constitution was based on ‘a fascist model, in which women would be relegated to permanent inferiority, their avoca- tions and choice of callings limited because of an implied invalidism as the weaker sex’.2 A fully independent Republic of Ireland came into being in 1949, in a decade that was framed by De Valera’s patriotic speech: ‘The Ireland that we dreamed of’. -

The Quest for Freedom in Tennessee Williams' the Rose Tattoo And

Novita Dewi The Quest for Freedom in Tennessee Williams’ The Rose Tattoo and Sweet Bird of Youth Novita Dewi English Language Studies, Sanata Dharma University [email protected] Abstract This paper examines the interface of economic hardship, sexual repression, and fear of aging in Tennessee Williams’ plays of the 1950s. Set in modern capitalist society of America, The Rose Tattoo (1955) and Sweet Bird of Youth (1959) depict the characters who are thwarted in their search for freedom that can be equated with the celebration of material prosperity and eternal youth. Using Eric Fromm’s view of freedom-as-frightful in modern society, the discussion will reveal the entrapment of self-deception in the characters’ unrealistic hope to stay young and productive in a commercialised society where sex is a commodity. Keywords: economic hardship, sexual repression, fear of aging Introduction all absorbed in a pursuit of freedom, and this aspect has not been well documented. Numerous critics have labelled Throughout his plays, Williams portrays Tennessee Williams an erotic writer and a characters whose sex drive is born largely out disciple of D. H. Lawrence because of his of their desire to free themselves from other intense preoccupation with sex in most of his restrictions. Psychoanalysis assumes that the plays. Hirsch (1979: 4), for example, says that urge for sexual action is inextricably linked to Williams was a “confused moralist”, who the drive for power which is often believed that sex was something like “grace”, synonymous with freedom (Benson, 1974: and at the same time “impure”. In discussing 211). Thus freedom is related to the ability to Sweet Bird of Youth, Falk (1961) contends achieve one’s goal, one’s happiness, and one’s that Williams’ creativity began to decrease pleasure; and sex is only one instance of with the appearance of this sexually expression and fulfilment on the road to obsessive play. -

The Rose Tattoo by Tennessee Williams

Presents The Rose Tattoo by Tennessee Williams directed by Lauryl Lee Johnson Lydia Mendelssohn Theatre Ann Arbor, Michigan THIRTY-NINTH SEASON Cast Notes ELIZABETH KAHN (Rosa) is appearing before AACT audiences for the first time. A student at Huron High School, Elizabeth has performed in AAHS "Tom Jones", Junior Light Opera "Henry, Sweet Henry" and gained tech experience in other productions with the AA Recreation Dept. and AAHS Theatre Guild. JAN STOLAREVSKY (Assunta) is stepping from backstage, where she served as stage manager on South Pacific, to performing for AACT audiences. Jan has experience with the Cincinnati Actor's Guild, Cincinnati State, Inc., and with the U. of M. Players. In real life, Jan is a teacher. MADELEINE RAMSEY (Serafina) new to our audiences, most recently appeared in the U. of M. Greek Tragedy Series as Electra and Medea. While in New York, she studied with Uta Hagen, and has experience in both college and community theatre. A teacher, Madeleine is the proud mother of Jonathan and Jennifer. DOROTHY MAPLES (Estelle) is well known to AACT audiences, having portrayed Mary in "Mary, Mary," and Claire in "The Visit". Those of you who have attended the Workshop one acts saw Dorothy in the production of " Ring Once for Central". Dorothy's other role in life is that of a teacher at Thurston. FRAN STEWART (The Strega) has had all kinds of experience in AACT, having served as Assistant Director on "Night of The Iguana", "Never Too Late", "All The Way Home", "The Mousetrap", and "South Pacitic". Previously with Wayne Civic Theatre, Fran performed in many of their productions. -

University Microilms International 300 N

MAUREEN STAPLETON, AMERICAN ACTRESS. Item Type text; Thesis-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Rosen, Esther. Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 23/09/2021 12:15:27 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/274791 INFORMATION TO USERS This reproduction was made from a copy of a document sent to us for microfilming. While the most advanced technology has been used to photograph and reproduce this document, the quality of the reproduction is heavily dependent upon the quality of the material submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help clarify markings or notations which may appear on this reproduction. 1.The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting through an image and duplicating adjacent pages to assure complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a round black mark, it is an indication of either blurred copy because of movement during exposure, duplicate copy, or copyrighted materials that should not have been filmed. For blurred pages, a good image of the page can be found in the adjacent frame. If copyrighted materials were deleted, a target note will appear listing the pages in the adjacent frame.