Interchapter Ii: 1940–1969

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Transcultural Perspective on the Casting of the Rose Tattoo

RSA JOU R N A L 25/2014 GIULIANA MUS C IO A Transcultural Perspective on the Casting of The Rose Tattoo A transcultural perspective on the film The Rose Tattoo (Daniel Mann, 1955), written by Tennessee Williams, is motivated by its setting in an Italian-American community (specifically Sicilian) in Louisiana, and by its cast, which includes relevant Italian participation. A re-examination of its production and textuality illuminates not only Williams’ work but also the cultural interactions between Italy and the U.S. On the background, the popularity and critical appreciation of neorealist cinema.1 The production of the film The Rose Tattoo has a complicated history, which is worth recalling, in order to capture its peculiar transcultural implications in Williams’ own work, moving from some biographical elements. In the late 1940s Tennessee Williams was often traveling in Italy, and visited Sicily, invited by Luchino Visconti (who had directed The Glass Managerie in Rome, in 1946) for the shooting of La terra trema (1948), where he went with his partner Frank Merlo, an occasional actor of Sicilian origins (Williams, Notebooks 472). Thus his Italian experiences involved both his professional life, putting him in touch with the lively world of Italian postwar theater and film, and his affections, with new encounters and new friends. In the early 1950s Williams wrote The Rose Tattoo as a play for Anna Magnani, protagonist of the neorealist masterpiece Rome Open City (Roberto Rossellini, 1945). However, the Italian actress was not yet comfortable with acting in English and therefore the American stage version (1951) starred Maureen Stapleton instead and Method actor Eli Wallach. -

The Dublin Gate Theatre Archive, 1928 - 1979

Charles Deering McCormick Library of Special Collections Northwestern University Libraries Dublin Gate Theatre Archive The Dublin Gate Theatre Archive, 1928 - 1979 History: The Dublin Gate Theatre was founded by Hilton Edwards (1903-1982) and Micheál MacLiammóir (1899-1978), two Englishmen who had met touring in Ireland with Anew McMaster's acting company. Edwards was a singer and established Shakespearian actor, and MacLiammóir, actually born Alfred Michael Willmore, had been a noted child actor, then a graphic artist, student of Gaelic, and enthusiast of Celtic culture. Taking their company’s name from Peter Godfrey’s Gate Theatre Studio in London, the young actors' goal was to produce and re-interpret world drama in Dublin, classic and contemporary, providing a new kind of theatre in addition to the established Abbey and its purely Irish plays. Beginning in 1928 in the Peacock Theatre for two seasons, and then in the theatre of the eighteenth century Rotunda Buildings, the two founders, with Edwards as actor, producer and lighting expert, and MacLiammóir as star, costume and scenery designer, along with their supporting board of directors, gave Dublin, and other cities when touring, a long and eclectic list of plays. The Dublin Gate Theatre produced, with their imaginative and innovative style, over 400 different works from Sophocles, Shakespeare, Congreve, Chekhov, Ibsen, O’Neill, Wilde, Shaw, Yeats and many others. They also introduced plays from younger Irish playwrights such as Denis Johnston, Mary Manning, Maura Laverty, Brian Friel, Fr. Desmond Forristal and Micheál MacLiammóir himself. Until his death early in 1978, the year of the Gate’s 50th Anniversary, MacLiammóir wrote, as well as acted and designed for the Gate, plays, revues and three one-man shows, and translated and adapted those of other authors. -

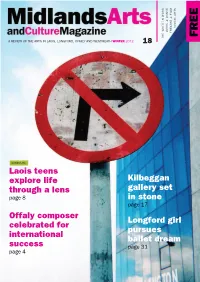

Issue 18 Midlands Arts 4:Layout 1

VISUAL ARTS MUSIC & DANCE ISSUE & FILM THEATRE FREE THE WRITTEN WORD A REVIEW OF THE ARTS IN LAOIS, LONGFORD, OFFALY AND WESTMEATH WINTER 2012 18 COVER PIC Laois teens explore life Kilbeggan through a lens gallery set page 8 in stone page 17 Offaly composer Longford girl celebrated for pursues international ballet dream success page 31 page 4 Toy Soldiers, wins at Galway Film Fleadh Midland Arts and Culture Magazine | WINTER 2010 Over two decades of Arts and Culture Celebrated with Presidential Visit ....................................................................Page 3 A Word Laois native to trend the boards of the Gaiety Theatre Midlands Offaly composer celebrated for international success .....Page 4 from the American publisher snaps up Longford writer’s novel andCulture Leaves Literary Festival 2012 celebrates the literary arts in Laois on November 9, 10............................Page 5 Editor Arts Magazine Backstage project sees new Artist in Residence There has been so Irish Iranian collaboration results in documentary much going on around production .....................................................................Page 6 the counties of Laois, Something for every child Mullingar Arts Centre! Westmeath, Offaly Fear Sean Chruacháin................................................Page 7 and Longford that County Longford writers honored again we have had to Laois teens explore life through the lens...............Page 8 up the pages from 32 to 36 just to fit Introducing Pete Kennedy everything in. Making ‘Friends’ The Doctor -

Anniversary Season

th ASOLO REPERTORY THEATRE o ANNIVERSARY6 SEASON ASOLO REPERTORY THEATRE th 6oANNIVERSARY DINNER November 26, 2018 The Westin | Sarasota 6pm | Cocktail Reception 7pm | Dinner, Presentation and Award Ceremony • Vic Meyrich Tech Award • Bradford Wallace Acting Award 03 HONOREES Honoring 12 artists who made an indelible impact on the first decade and beyond. 04-05 WELCOME LETTER 06-11 60 YEARS OF HISTORY 12-23 HONOREE INTERVIEWS 24-27 LIST OF PRODUCTIONS From 1959 through today rep 31 TRIBUTES o l aso HONOREES Steve Hogan Assistant Technical Director, 1969-1982 Master Carpenter, 1982-2001 Shop Foreman, 2001-Present Polly Holliday Resident Acting Company, 1962-1972 Vic Meyrich Technical Director, 1968-1992 Production Manager, 1992-2017 Production Manager & Operations Director, 2017-Present Howard Millman Actor, 1959 Managing Director, Stage Director, 1968-1980 Producing Artistic Director, 1995-2006 Stephanie Moss Resident Acting Company, 1969-1970 Assistant Stage Manager, 1972-1990 Bob Naismith Property Master, 1967-2000 Barbara Redmond Resident Acting Company, 1968-2011 Director, Playwright, 1996-2003 Acting Faculty/Head of Acting, FSU/Asolo Conservatory, 1998-2011 Sharon Spelman Resident Acting Company, 1968-1971 and 1996-2010 Eberle Thomas Director, Actor, Playwright, 1960-1966 rep Co-Artistic Director, 1966-1973 Director, Actor, Playwright, 1976-2007 Brad Wallace o Resident Acting Company, 1961-2008 l Marian Wallace Box Office Associate, 1967-1968 Stage Manager, 1968-1969 Production Stage Manager, 1969-2010 John M. Wilson Master Carpenter, 1969-1977 asolorep.org | 03 aso We are grateful you are here tonight to celebrate and support Asolo Rep — MDE/LDG PHOTO WHICH ONE ??? Nationally renowned, world-class theatre, made in Sarasota. -

William and Mary Theatre Main Stage Productions

WILLIAM AND MARY THEATRE MAIN STAGE PRODUCTIONS 1926-1927 1934-1935 1941-1942 The Goose Hangs High The Ghosts of Windsor Park Gas Light Arms and the Man Family Portrait 1927-1928 The Romantic Age The School for Husbands You and I The Jealous Wife Hedda Gabler Outward Bound 1935-1936 1942-1943 1928-1929 The Unattainable Thunder Rock The Enemy The Lying Valet The Male Animal The Taming of the Shrew The Cradle Song *Bach to Methuselah, Part I Candida Twelfth Night *Man of Destiny Squaring the Circle 1929-1930 1936-1937 The Mollusc Squaring the Circle 1943-1944 Anna Christie Death Takes a Holiday Papa is All Twelfth Night The Gondoliers The Patriots The Royal Family A Trip to Scarborough Tartuffe Noah Candida 1930-1931 Vergilian Pageant 1937-1938 1944-1945 The Importance of Being Earnest The Night of January Sixteenth Quality Street Just Suppose First Lady Juno and the Paycock The Merchant of Venice The Mikado Volpone Enter Madame Liliom Private Lives 1931-1932 1938-1939 1945-1946 Sun-Up Post Road Pygmalion Berkeley Square RUR Murder in the Cathedral John Ferguson The Pirates of Penzance Ladies in Retirement As You Like It Dear Brutus Too Many Husbands 1932-1933 1939-1940 1946-1947 Outward Bound The Inspector General Arsenic and Old Lace Holiday Kind Lady Arms and the Man The Recruiting Officer Our Town The Comedy of Errors Much Ado About Nothing Hay Fever Joan of Lorraine 1933-1934 1940-1941 1947-1948 Quality Street You Can’t Take It with You The Skin of Our Teeth Hotel Universe Night Must Fall Blithe Spirit The Swan Mary of Scotland MacBeth -

Cois Coiribe 2016

COIRIBE COIS Rio The Magazine for GOLD NUI Galway Galway 2020 MedTech in Galway A Changing Campus Alumni & Friends Autumn 2016 NUI Galway Affinity Card. You get, we give. You get a unique credit card and we give back to NUI Galway when you register and each year your Affinity card is active. Our introductory offer gives you a competitive rate of 2.9%¹ APR interest on balance transfers for first 12 months. bankofireland.com/alumni 1890 365 100 Lending criteria terms and conditions apply to all credit cards. Credit cards are liable to Government Stamp Duty of €30. Credit cannot be offered to anyone under 18 years of age. Bank of Ireland is regulated by the Central Bank of Ireland. ¹Available if you don’t currently hold a credit card with Bank of Ireland, whether you have an account with us or not. At the end of the introductory period the annual interest rates revert back to 2 COIS COIRIBEthe standard rate applicable to your card at that time. OMI008172 - NUIG Affinity A4_Portrait Ad_v13.indd 1 03/08/2016 12:35 NUI Galway CONTENTS 2 FOCAL ÓN UACHTARÁN NEWS Affinity Card. 4 The Year in Pictures 6 Research Round-up 10 University News You get, we give. 14 Campus News 26 Student Success FEATURES 16 A New Direction for Sport 22 1916 – Centenary Year 4 24 NASA Mission 28 A Changing Campus - Capital Development 32 Giving Stem Cells a heartbeat 34 MedTech in Galway 24 41 TG4 @ 20 42 Galway 2020 GRADUATES 36 Aoibheann McNamara 37 Paul O’Hara 38 Grads in Silicon Valley 44 Graduations GALWAY UNIVERSITY FOUNDATION 46 Empowering Excellence ALUMNI 6 18 50 Alumni Awards 38 52 Alumni Events 56 Class Notes 64 Obituaries CONTRIBUTORS Jo Lavelle, John Fallon, Ronan McGreevy, Joyce McCreevy, Joe Connolly, Dónall Ó Braonáin, Conor McNamara, Liz McConnell, Ruth Hynes, Sheila Gorham. -

History of Intiman

INTIMAN THEATRE PRODUCTION HISTORY 1972-2012 PLAY AUTHOR DIRECTOR 1972-73 Rosmersholm Ibsen (trans. Michael Meyer) Margaret Booker The Creditors Strindberg (trans. Walter Johnson) Margaret Booker The Underpants Carl Sternheim (trans. Eric Bentley) Margaret Booker 1974 Brecht on Brecht George Tabori Andrew Witt Miss Julie Strindberg (trans. Margaret Booker) Margaret Booker Tango Slaw omir Mrozek Margaret Booker Candida George Bernard Shaw Margaret Booker 1975 Uncle Vanya Chekhov (trans. Christopher Hampton) Margaret Booker The Philanderer George Bernard Shaw Margaret Booker Hedda Gabler Ibsen (trans. Margaret Booker) Margaret Booker 1976 Arms and the Man George Bernard Shaw Stephen Rosenfield Elektra Sophocles (trans. David Grene) Margaret Booker Anatol Arthur Schnitzler Margaret Booker Bus Stop William Inge Pat Patton The Northw est Show Barry Pritchard Margaret Booker 1977 Toys in the Attic Lillian Hellman Margaret Booker The Importance of Being Earnest Oscar Wilde Clayton Corzatte Ghosts Ibsen (trans. Margaret Booker) Margaret Booker Playboy of the Western World John Millington Synge Pat Patton A Moon for the Misbegotten Eugene O' Neill Margaret Booker 1978 Henry IV Luigi Pirandello (adapt. John Reich) Margaret Booker The Way of the World William Congreve Anthony Cornish Three Sisters Chekhov Margaret Booker The Country Girl Clifford Odets Stephen Rosenfield The Dance of Death August Strindberg Margaret Booker 1979 The Loves of Cass McGuire Brian Friel Margaret Booker Tartuffe Molière (trans. Richard Wilbur) Stephen Rosenfield Medea Euripides (adapt. Robinson Jeffers) Margaret Booker Heartbreak House George Bernard Shaw Anthony Cornish Design for Living Noë l Cow ard Margaret Booker 1980 Othello William Shakespeare Margaret Booker The Lady's Not for Burning Christopher Fry William Glover Leonce and Lena Georg Bü chner Margaret Booker (trans. -

Negotiating Ireland – Some Notes for Interns

Welcome to Ireland – General Notes for Interns (2015 – will be updated for 2016 in January 2016) Fergus Ryan These notes are designed to introduce you to Ireland and to address any questions you might have concerning practical aspects about your visit to Ireland. About Ireland Ireland is an island on the north- financial services. The official west coast of Europe, with a languages are English and Irish. population of approximately 6.3 While English is the main language million inhabitants. It is of communication, Irish is spoken on approximately 32,600 square miles, a daily basis in some parts of the 300 miles from the northern most west, while over half a million tip to the most southern, and inhabitants speak a language other approximately 175 miles across, than English or Irish at home. making it just a little under half the (Sources: CSO Census 2011, size of Oklahoma State. www.cso.ie) Politically, the island comprises two Northern Ireland comprises six legal entities. The Republic of counties in the northeast corner of Ireland, with 4.6 million the island. A jurisdiction within the inhabitants, makes up the bulk of the United Kingdom, it has just over 1.8 island. The State attained million people. It has its own power- independence from the UK in 1922, sharing parliament and government and became a Republic in 1949. The with significant devolved powers Republic of Ireland is a sovereign, and functions. Its capital and largest democratic republic, with its current city is Belfast. Northern Ireland is Constitution dating back to 1937. It politically divided along religious is a member of the European Union lines: 48% of those in Northern and the Council of Europe, but is Ireland are Protestant or were militarily non-aligned. -

Irish Responses to Fascist Italy, 1919–1932 by Mark Phelan

Provided by the author(s) and NUI Galway in accordance with publisher policies. Please cite the published version when available. Title Irish responses to Fascist Italy, 1919-1932 Author(s) Phelan, Mark Publication Date 2013-01-07 Item record http://hdl.handle.net/10379/3401 Downloaded 2021-09-27T09:47:44Z Some rights reserved. For more information, please see the item record link above. Irish responses to Fascist Italy, 1919–1932 by Mark Phelan A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Supervisor: Prof. Gearóid Ó Tuathaigh Department of History School of Humanities National University of Ireland, Galway December 2012 ABSTRACT This project assesses the impact of the first fascist power, its ethos and propaganda, on key constituencies of opinion in the Irish Free State. Accordingly, it explores the attitudes, views and concerns expressed by members of religious organisations; prominent journalists and academics; government officials/supporters and other members of the political class in Ireland, including republican and labour activists. By contextualising the Irish response to Fascist Italy within the wider patterns of cultural, political and ecclesiastical life in the Free State, the project provides original insights into the configuration of ideology and social forces in post-independence Ireland. Structurally, the thesis begins with a two-chapter account of conflicting confessional responses to Italian Fascism, followed by an analysis of diplomatic intercourse between Ireland and Italy. Next, the thesis examines some controversial policies pursued by Cumann na nGaedheal, and assesses their links to similar Fascist initiatives. The penultimate chapter focuses upon the remarkably ambiguous attitude to Mussolini’s Italy demonstrated by early Fianna Fáil, whilst the final section recounts the intensely hostile response of the Irish labour movement, both to the Italian regime, and indeed to Mussolini’s Irish apologists. -

All We Say Is 'Life Is Crazy': – Central and Eastern Europe and the Irish

Provided by the author(s) and NUI Galway in accordance with publisher policies. Please cite the published version when available. Title All we say is 'Life is crazy': - Central and Eastern Europe and the Irish Stage Author(s) Lonergan, Patrick Publication Date 2009 Lonergan, P. (2009) ' All we say is 'Life is Crazy': - Central and Publication Eastern Europe and the Irish Stage' In: Maria Kurdi, Literary Information and Cultural Relations Between Ireland and Hungary and Central and Eastern Europe' (Eds.) Dublin: Carysfort Press. Publisher Dublin: Carysfort Press Link to publisher's http://www.carysfortpress.com/ version Item record http://hdl.handle.net/10379/5361 Downloaded 2021-09-28T21:11:04Z Some rights reserved. For more information, please see the item record link above. All We Say is ‘Life is Crazy’: – Central and Eastern Europe and the Irish Stage Patrick Lonergan If you had visited the Abbey Theatre during 2007, you might have seen a card displayed prominently in its foyer. ‘Join Us,’ it says, its purpose being to convince visitors to become Members of the Abbey – to donate money to the theatre and, in return, to get free tickets for productions, to have their names listed in show programmes, and to gain access to special events. The choice of image to attract potential donors is easy to understand (Figure 1). The woman, we see, has reached into a chandelier to retrieve a letter, and we can tell from her expression that the discovery she’s made has both surprised and delighted her. Why is she so happy? What does the letter say? And who is that strange man, barely visible, holding her up at such an unusual angle? As well as being eye-catching, the image is also an interesting analogue for the experience of watching great drama. -

2017 Katie Roche, Research Pack

ABBEY THEATRE RESEARCH PACK KATIE ROCHE TERESA DEEVY Researched and compiled by Marie Kelly (School of Music and Theatre, University College Cork) CONTRIBUTORS Fiona Becket, University of Leeds Caroline Byrne, theatre director Amanda Coogan, performance artist Úna Kealy, Waterford Institute of Technology Marie Kelly, University College Cork Cathy Leeney, University College Dublin Chris Morash, Trinity College Dublin Kate McCarthy, Waterford Institute of Technology Barbara McCormack, Hugh Murphy, Valerie Payne, Róisín Berry, Maynooth University Morna Regan, dramaturg/writer Eibhear Walshe, University College Cork With special thanks to the Abbey Theatre Archive and the Teresa Deevy Archive, Special Collections & Archives, Maynooth University, Co. Kildare. For more information see https://www.abbeytheatre. ie/about/archive/ and www.deevy.nuim.ie Cover Image: Caoilfhionn Dunne as Katie Roche © Ros Kavanagh KATIE ROCHE, RESEARCH PACK 2 WELCOME PHIL KINGSTON From 26 August to 23 September 2017, the dramaturgy and Caroline Byrne’s expressionistic Abbey Theatre presented a major revival of staging turned this Katie Roche into far more Teresa Deevy’s ground-breaking play Katie than a reverential museum piece. The audiences Community and Roche. It was over 80 years since this daring saw a specific, thrilling and thought provoking Education Manager meditation on freedom, duty and pride in take on Deevy’s classic story. Coincidentally at the life of a young woman made its world the same time another artist, Amanda Coogan, premiere on the Abbey stage. presented a performance art based response to Deevy’s work in collaboration with Dublin In its initial press release the Abbey explicitly Theatre of the Deaf in Talk Real Fine, Just Like A recognised that the political climate had Lady. -

Austin Clarke Papers

Leabharlann Náisiúnta na hÉireann National Library of Ireland Collection List No. 83 Austin Clarke Papers (MSS 38,651-38,708) (Accession no. 5615) Correspondence, drafts of poetry, plays and prose, broadcast scripts, notebooks, press cuttings and miscellanea related to Austin Clarke and Joseph Campbell Compiled by Dr Mary Shine Thompson 2003 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction 7 Abbreviations 7 The Papers 7 Austin Clarke 8 I Correspendence 11 I.i Letters to Clarke 12 I.i.1 Names beginning with “A” 12 I.i.1.A General 12 I.i.1.B Abbey Theatre 13 I.i.1.C AE (George Russell) 13 I.i.1.D Andrew Melrose, Publishers 13 I.i.1.E American Irish Foundation 13 I.i.1.F Arena (Periodical) 13 I.i.1.G Ariel (Periodical) 13 I.i.1.H Arts Council of Ireland 14 I.i.2 Names beginning with “B” 14 I.i.2.A General 14 I.i.2.B John Betjeman 15 I.i.2.C Gordon Bottomley 16 I.i.2.D British Broadcasting Corporation 17 I.i.2.E British Council 17 I.i.2.F Hubert and Peggy Butler 17 I.i.3 Names beginning with “C” 17 I.i.3.A General 17 I.i.3.B Cahill and Company 20 I.i.3.C Joseph Campbell 20 I.i.3.D David H. Charles, solicitor 20 I.i.3.E Richard Church 20 I.i.3.F Padraic Colum 21 I.i.3.G Maurice Craig 21 I.i.3.H Curtis Brown, publisher 21 I.i.4 Names beginning with “D” 21 I.i.4.A General 21 I.i.4.B Leslie Daiken 23 I.i.4.C Aodh De Blacam 24 I.i.4.D Decca Record Company 24 I.i.4.E Alan Denson 24 I.i.4.F Dolmen Press 24 I.i.5 Names beginning with “E” 25 I.i.6 Names beginning with “F” 26 I.i.6.A General 26 I.i.6.B Padraic Fallon 28 2 I.i.6.C Robert Farren 28 I.i.6.D Frank Hollings Rare Books 29 I.i.7 Names beginning with “G” 29 I.i.7.A General 29 I.i.7.B George Allen and Unwin 31 I.i.7.C Monk Gibbon 32 I.i.8 Names beginning with “H” 32 I.i.8.A General 32 I.i.8.B Seamus Heaney 35 I.i.8.C John Hewitt 35 I.i.8.D F.R.