Pediatric Pharmacotherapy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Guidelines for the Forensic Analysis of Drugs Facilitating Sexual Assault and Other Criminal Acts

Vienna International Centre, PO Box 500, 1400 Vienna, Austria Tel.: (+43-1) 26060-0, Fax: (+43-1) 26060-5866, www.unodc.org Guidelines for the Forensic analysis of drugs facilitating sexual assault and other criminal acts United Nations publication Printed in Austria ST/NAR/45 *1186331*V.11-86331—December 2011 —300 Photo credits: UNODC Photo Library, iStock.com/Abel Mitja Varela Laboratory and Scientific Section UNITED NATIONS OFFICE ON DRUGS AND CRIME Vienna Guidelines for the forensic analysis of drugs facilitating sexual assault and other criminal acts UNITED NATIONS New York, 2011 ST/NAR/45 © United Nations, December 2011. All rights reserved. The designations employed and the presentation of material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. This publication has not been formally edited. Publishing production: English, Publishing and Library Section, United Nations Office at Vienna. List of abbreviations . v Acknowledgements .......................................... vii 1. Introduction............................................. 1 1.1. Background ........................................ 1 1.2. Purpose and scope of the manual ...................... 2 2. Investigative and analytical challenges ....................... 5 3 Evidence collection ...................................... 9 3.1. Evidence collection kits .............................. 9 3.2. Sample transfer and storage........................... 10 3.3. Biological samples and sampling ...................... 11 3.4. Other samples ...................................... 12 4. Analytical considerations .................................. 13 4.1. Substances encountered in DFSA and other DFC cases .... 13 4.2. Procedures and analytical strategy...................... 14 4.3. Analytical methodology .............................. 15 4.4. -

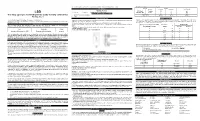

MSM Cross Reference Antihistamine Decongestant 20100701 Final Posted

MISSISSIPPI DIVISION OF MEDICAID Antihistamine/Decongestant Product and Active Ingredient Cross-Reference List The agents listed below are the antihistamine/decongestant drug products listed in the Mississippi Medicaid Preferred Drug List (PDL). This is a cross-reference between the drug product name and its active ingredients to reference the antihistamine/decongestant portion of the PDL. For more information concerning the PDL, including non- preferred agents, the OTC formulary, and other specifics, please visit our website at www.medicaid.ms.gov. List Effective 07/16/10 Therapeutic Class Active Ingredients Preferred Non-Preferred ANTIHISTAMINES - 1ST GENERATION BROMPHENIRAMINE MALEATE BPM BROMAX BROMPHENIRAMINE MALEATE J-TAN PD BROMSPIRO LODRANE 24 LOHIST 12HR VAZOL BROMPHENIRAMINE TANNATE BROMPHENIRAMINE TANNATE J-TAN P-TEX BROMPHENIRAMINE/DIPHENHYDRAM ALA-HIST CARBINOXAMINE MALEATE CARBINOXAMINE MALEATE PALGIC CHLORPHENIRAMINE MALEATE CHLORPHENIRAMINE MALEATE CPM 12 CHLORPHENIRAMINE TANNATE ED CHLORPED ED-CHLOR-TAN MYCI CHLOR-TAN MYCI CHLORPED PEDIAPHYL TANAHIST-PD CLEMASTINE FUMARATE CLEMASTINE FUMARATE CYPROHEPTADINE HCL CYPROHEPTADINE HCL DEXCHLORPHENIRAMINE MALEATE DEXCHLORPHENIRAMINE MALEATE DIPHENHYDRAMINE HCL ALLERGY MEDICINE ALLERGY RELIEF BANOPHEN BENADRYL BENADRYL ALLERGY CHILDREN'S ALLERGY CHILDREN'S COLD & ALLERGY COMPLETE ALLERGY DIPHEDRYL DIPHENDRYL DIPHENHIST DIPHENHYDRAMINE HCL DYTUSS GENAHIST HYDRAMINE MEDI-PHEDRYL PHARBEDRYL Q-DRYL QUENALIN SILADRYL SILPHEN DIPHENHYDRAMINE TANNATE DIPHENMAX DOXYLAMINE SUCCINATE -

Brompheniramine Maleate, Pseudoephedrine Hydrochloride

BROMPHENIRAMINE MALEATE, PSEUDOEPHEDRINE HYDROCHLORIDE, AND DEXTROMETHORPHAN HYDROBROMIDE- brompheniramine maleate, pseudoephedrine hydrochloride, and dextromethorphan hydrobromide syrup Morton Grove Pharmaceuticals, Inc. ---------- Brompheniramine Maleate, Pseudoephedrine Hydrochloride, and Dextromethorphan Hydrobromide Oral Syrup 2 mg/30 mg/10 mg per 5 mL Rx only DESCRIPTION Brompheniramine Maleate, Pseudoephedrine Hydrochloride and Dextromethorphan Hydrobromide Oral Syrup is a clear, light pink syrup with a butterscotch flavor. Each 5 mL (1 teaspoonful) contains: Brompheniramine Maleate, USP 2 mg Pseudoephedrine Hydrochloride, USP 30 mg Dextromethorphan Hydrobromide, USP 10 mg Alcohol 0.95% v/v In a palatable, aromatic vehicle. Inactive Ingredients: artificial butterscotch flavor, citric acid anhydrous, dehydrated alcohol, FD&C Red No. 40, glycerin, liquid sugar, methylparaben, propylene glycol, purified water and sodium benzoate. It may contain 10% citric acid solution or 10% sodium citrate solution for pH adjustment. The pH range is between 3.0 and 6.0. C16H19BrN2·C4H4O4 M.W. 435.31 Brompheniramine Maleate, USP (±)-2-p-Bromo-α-2-(dimethylamino)ethylbenzylpyridine maleate (1:1) C10H15NO · HCl M.W. 201.69 Pseudoephedrine Hydrochloride, USP (+)-Pseudoephedrine hydrochloride C18H25NO · HBr · H2O M.W. 370.32 Dextromethorphan Hydrobromide, USP 3-Methoxy-17-methyl-9α, 13α, 14α -morphinan hydrobromide monohydrate Antihistamine/Nasal Decongestant/Antitussive syrup for oral administration. CLINICAL PHARMACOLOGY Brompheniramine maleate is a -

Title 16. Crimes and Offenses Chapter 13. Controlled Substances Article 1

TITLE 16. CRIMES AND OFFENSES CHAPTER 13. CONTROLLED SUBSTANCES ARTICLE 1. GENERAL PROVISIONS § 16-13-1. Drug related objects (a) As used in this Code section, the term: (1) "Controlled substance" shall have the same meaning as defined in Article 2 of this chapter, relating to controlled substances. For the purposes of this Code section, the term "controlled substance" shall include marijuana as defined by paragraph (16) of Code Section 16-13-21. (2) "Dangerous drug" shall have the same meaning as defined in Article 3 of this chapter, relating to dangerous drugs. (3) "Drug related object" means any machine, instrument, tool, equipment, contrivance, or device which an average person would reasonably conclude is intended to be used for one or more of the following purposes: (A) To introduce into the human body any dangerous drug or controlled substance under circumstances in violation of the laws of this state; (B) To enhance the effect on the human body of any dangerous drug or controlled substance under circumstances in violation of the laws of this state; (C) To conceal any quantity of any dangerous drug or controlled substance under circumstances in violation of the laws of this state; or (D) To test the strength, effectiveness, or purity of any dangerous drug or controlled substance under circumstances in violation of the laws of this state. (4) "Knowingly" means having general knowledge that a machine, instrument, tool, item of equipment, contrivance, or device is a drug related object or having reasonable grounds to believe that any such object is or may, to an average person, appear to be a drug related object. -

Prescribing Information for High-Dose Fexofenadine in the Management of Urticaria in Adults

1 Prescribing information for high-dose fexofenadine in the management of urticaria in adults This prescribing information document outlines the prescribing responsibilities between the specialist and GP. GPs are invited to participate. If the GP feels that such prescribing is outside their area of expertise or have clinical concerns about the safe management of the drug in primary care, then he or she is under no obligation to do so. In such an event, clinical responsibility for the patient’s health remains with the specialist. If a specialist asks the GP to prescribe, the GP should reply to this request as soon as practicable. Consultant details GP details Patient details Name: Name: Name: Address: Address: NHS Number: Email: Email: Date of birth: Contact number: Contact number: Contact: Introduction Fexofenadine is a second generation non-sedating H1-antihistamine used in the treatment of allergic disorders. Fexofenadine is a pharmacologically active metabolite of terfenadine. Licensed indication: In adults and children 12 years and older, the licensed dose is 180mg daily for the relief of symptoms associated with chronic idiopathic urticaria. Unlicensed indication (the focus of this document): As advised by Europeani and British Association of Dermatologistsii guidelines, doses of antihistamines up to four times the recommended daily dose may be used in the treatment of urticaria. Adult dosage and administration The licensed maximum recommended daily dose is 180mg once daily taken before a meal. Doses of up to four times the daily recommended dose have been used in the treatment of severe urticaria (unlicensed indication)i Available as: 30mg, 120mg and 180mg tablets Specialist responsibilities Provide patient/carer with relevant written information on the unlicensed use of high-dose fexofenadine and possible side-effects. -

The Effect of Bromepheniramine on Cough Sensitivity in Normal Volunteers

THE EFFECT OF BROMPHENIRAMINE ON COUGH SENSITIVITY IN HEALTHY VOLUNTEERS Haytham M. El-Khushman MD* ABSTRACT Objective: To evaluate the anti-tussive effect of brompheniramine maleate a non-selective, sedative antihistamine using capsaicin challenge. Methods: Twelve subjects, five females and seven females, mean age 32 years with a range of (23-39) years, were studied on two occasions. On the two visits a baseline capsaicin dose-response was performed to determine C5 (the lowest concentration causing 5 coughs). After 30 minutes two C5 doses of capsaicin were given and the total cough over one minute was counted. On the first visit Brompheniramine 8mg or a matched placebo was given orally, and 120, 240 minutes after administration, two C5 doses of capsaicin were given and the total coughs over one minute period were counted. This was repeated exactly in the second visit except subjects received either a placebo or active treatment; either which they had not received on their first visit. Subjects were also asked to quantify their drowsiness using a 100 mm visual analogue scale. Results: Baseline mean cough number (confidence interval) was similar on the two study occasions 9.9 (8.2-11.7) before Brompheniramine and 9.2 (7.3-11.1) before placebo. Cough number did not differ on the two study days at 120 and 240 min after Brompheniramine treatment: 7.7 (5.5-9.8), 7.4 (5.1-9.6) compared to 8.7 (6.4-11.0), 8.3 (6.8- 9.8) after placebo. Mean visual analogue scale (confidence interval) after Brompheniramine was 31 (14-48) and 40 (21-60) compared to 7 (2-12) and 7 (2-12) after Placebo at 120 and 240 min respectively (p<0.008). -

Profile Profile Profile Profile Uses and Administration Adverse Effects And

640 Antihistamines Propiomazine Hydrochloride {BANM, r!NNMJ P..r�p�rc:Jti()n.� ............................ m (details are given in Volume B) propiorf,azina; to o azine; Chiorhydrate ProprietaryPreparations HidrodoruroPropi<;>rn deazini HydrochloridP pium; f1ponvtot,la3Y!Ha China: Qi Qi Hung. : de; Single-ingredient Preparafions. Loderixt. CIH'f); rMAPOX!10p!'\A. C;cJcl1_,--N_,QS,HCI�3.76_91 Rupatadine is an antihistamine with platelet-activating CAS 240) 5-9. factor (PAF) antagonist activity that is used for the Terfenadine (BAN, USAN, r!NN) treatment of allergic rhinitis (p. 612.1) and chronic 1 idiopathic urticaria (p. 612.3). It is given as the fumarate although doses are expressed in terms of the base; rupatadine fumarate 12.8 mg is equivalent to about 10 mg of rupatadine. The usual oral dose is the equivalent of 10 mg once daily of rupatadine. Izquierdo I. et a!. Rupatadine: a new selective histamine HI receptor and platelet-activating factor (PAF) antagonist: a review of pharmacological profile and clinical management of allergic rhinitis. Drugs Today 2003; 39: 451-68. 2. Kearn SJ,Plosker GL. Rupatadine: a review of its use in the management of allergic disorders. Drugs 2007; 67: 457-74. 3. Fantin et at. International Rupatadine study group. A 12-week 5, 8: (Terfenadine). A white or almost white, placebo-controlled study of rupatadine 10 mg once daily compared with Ph. Bur. cetirizine IO mg once daily, in the treatment of persistent allergic crystalline powder. It shows polymorphism. Very slightly rhinitis. Allergy 2008; 63: 924-3 1. soluble in water and in dilute hydrochloric acid; freely 4. -

Antihistamines in the Treatment of Chronic Urticaria I Jáuregui,1 M Ferrer,2 J Montoro,3 I Dávila,4 J Bartra,5 a Del Cuvillo,6 J Mullol,7 J Sastre,8 a Valero5

Antihistamines in the treatment of chronic urticaria I Jáuregui,1 M Ferrer,2 J Montoro,3 I Dávila,4 J Bartra,5 A del Cuvillo,6 J Mullol,7 J Sastre,8 A Valero5 1 Service of Allergy, Hospital de Basurto, Bilbao, Spain 2 Department of Allergology, Clínica Universitaria de Navarra, Pamplona, Spain 3 Allergy Unit, Hospital La Plana, Villarreal (Castellón), Spain 4 Service of Immunoallergy, Hospital Clínico, Salamanca, Spain 5 Allergy Unit, Service of Pneumology and Respiratory Allergy, Hospital Clínic (ICT), Barcelona, Spain 6 Clínica Dr. Lobatón, Cádiz, Spain 7 Rhinology Unit, ENT Service (ICEMEQ), Hospital Clínic, Barcelona, Spain 8 Service of Allergy, Fundación Jiménez Díaz, Madrid, Spain ■ Summary Chronic urticaria is highly prevalent in the general population, and while there are multiple treatments for the disorder, the results obtained are not completely satisfactory. The second-generation H1 antihistamines remain the symptomatic treatment option of choice. Depending on the different pharmacokinetics and H1 receptor affi nity of each drug substance, different concentrations in skin can be expected, together with different effi cacy in relation to the histamine-induced wheal inhibition test - though this does not necessarily have repercussions upon clinical response. The antiinfl ammatory properties of the H1 antihistamines could be of relevance in chronic urticaria, though it is not clear to what degree they infl uence the fi nal therapeutic result. Before moving on to another therapeutic level, the advisability of antihistamine dose escalation should be considered, involving increments even above those approved in the Summary of Product Characteristics. Physical urticaria, when manifesting isolatedly, tends to respond well to H1 antihistamines, with the exception of genuine solar urticaria and delayed pressure urticaria. -

Antihistamine Therapy in Allergic Rhinitis

CLINICAL REVIEW Antihistamine Therapy in Allergic Rhinitis Paul R. Tarnasky, MD, and Paul P. Van Arsdel, Jr, MD Seattle, Washington Allergic rhinitis is a common disorder that is associated with a high incidence of mor bidity and considerable costs. The symptoms of allergic rhinitis are primarily depen dent upon the tissue effects of histamine. Antihistamines are the mainstay of therapy for allergic rhinitis. Recently, a second generation of antihistamines has become available. These agents lack the adverse effect of sedation, which is commonly associated with older antihistamines. Current practice of antihistamine therapy in allergic rhinitis often involves random selection among the various agents. Based upon the available clinical trials, chlorpheniramine appears to be the most reasonable initial antihistaminic agent. A nonsedating antihis tamine should be used initially if a patient is involved in activities where drowsiness is dangerous. In this comprehensive review of allergic rhinitis and its treatment, the cur rent as well as future options in antihistamine pharmacotherapy are emphasized. J Fam Pract 1990; 30:71-80. llergic rhinitis is a common condition afflicting some defined by the period of exposure to those agents to which A where between 15 and 30 million people in the United a patient is sensitive. Allergens in seasonal allergic rhinitis States.1-3 The prevalence of disease among adolescents is consist of pollens from nonflowering plants such as trees, estimated to be 20% to 30%. Two thirds of the adult grasses, and weeds. These pollens generally create symp allergic rhinitis patients are under 30 years of age.4-6 Con toms in early spring, late spring through early summer, sequently, considerable costs are incurred in days lost and fall, respectively. -

(LSD) Test Dip Card (Urine) • Specimen Collection Container % Agreement 98.8% 99

frozen and stored below -20°C. Frozen specimens should be thawed and mixed before testing. GC/MS. The following results were tabulated: Method GC/MS MATERIALS Total Results Results Positive Negative Materials Provided LSD Rapid Positive 79 1 80 LSD • Test device • Desiccants • Package insert • Urine cups Test Dip card Negative 1 99 100 Materials Required But Not Provided Total Results 80 100 180 One Step Lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD) Test Dip card (Urine) • Specimen collection container % Agreement 98.8% 99. % 98.9% • Timer Package Insert DIRECTIONS FOR USE Analytical Sensitivity This Instruction Sheet is for testing of Lysergic acid diethylamide. Allow the test device, and urine specimen to come to room temperature [15-30°C (59-86°F)] prior to testing. A drug-free urine pool was spiked with LSD at the following concentrations: 0 ng/mL, -50%cutoff, -25%cutoff, cutoff, A rapid, one step test for the qualitative detection of Lysergic acid diethylamide and its metabolites in human urine. 1) Remove the test device from the foil pouch. +25%cutoff and +50%cutoff. The result demonstrates >99% accuracy at 50% above and 50% below the cut-off For forensic use only. 2) Remove the cap from the test device. Label the device with patient or control identifications. concentration. The data are summarized below: INTENDED USE 3) Immerse the absorbent tip into the urine sample for 10-15 seconds. Urine sample should not touch the plastic Lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD) Percent of Visual Result The One Step Lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD) Test Dip card (Urine) is a lateral flow chromatographic device. -

Inhibitory Effect of Terfenadine, a Selective H1 Histamine Antagonist, on Alcoholic Beverage-Induced Bronchoconstriction in Asthmatic Patients

Eur Respir J, 1995, 8, 619–623 Copyright ERS Journals Ltd 1995 DOI: 10.1183/09031936.95.08040619 European Respiratory Journal Printed in UK - all rights reserved ISSN 0903 - 1936 Inhibitory effect of terfenadine, a selective H1 histamine antagonist, on alcoholic beverage-induced bronchoconstriction in asthmatic patients S. Myou*, M. Fujimura**, K. Nishi*, T. Ohka*, T. Matsuda** Inhibitory effect of terfenadine, a selective H1 histamine antagonist, on alcoholic bever- *Division of Respiratory Medicine, Ishikawa age-induced bronchoconstriction in asthmatic patients. S. Myou, M. Fujimura, K. Nishi, Prefectural Central Hospital, Kanazawa, T. Ohka, T. Matsuda. ERS Journals Ltd 1995. Japan. **The Third Dept of Internal Medicine, Kanazawa University School of ABSTRACT: We wanted to evaluate the effect of terfenadine, a selective H1-recep- tor antagonist, on alcoholic beverage-induced bronchoconstriction. Medicine, Kanazawa, Japan. Eight patients with alcohol-induced asthma received terfenadine (60 mg, twice on Correspondence: S. Myou the test day) or placebo, with the last dosing 2 h before the test in a double-blind, The Third Dept of Internal Medicine randomized, cross-over manner. On two separate study days, each subject drank Kanazawa University School of Medicine the same brand and volume of alcoholic beverage (beer or Japanese saké), and bron- 13-1 Takara-machi choconstriction was assessed as change in peak expiratory flow (PEF) over 120 min Kanazawa 920 postchallenge. Inhalation challenges were performed with the same alcoholic bev- Japan erage with which they had been orally challenged. Keywords: Alcohol The mean (SEM) percentage fall in PEF 15, 30, 45, 60, 90 and 120 min after the oral alcohol challenge was significantly reduced from 12.0 (3.1), 17.0 (1.7), 15.8 (2.3), asthma histamine 15.2 (3.4), 16.6 (4.8) and 14.7 (5.2) %, to 2.6 (1.8), 2.1 (1.6), 3.9 (1.2), 5.7 (2.2), 6.5 terfenadine (2.6), 5.1 (1.6) %, respectively, by terfenadine. -

Pre - PA Allowance Age 18 Years of Age Or Older Quantity 60 Grams Every 90 Days ______

DOXEPIN CREAM 5% (Prudoxin, Zonalon) Pre - PA Allowance Age 18 years of age or older Quantity 60 grams every 90 days _______________________________________________________________ Prior-Approval Requirements Age 18 years of age or older Diagnosis Patient must have the following: Moderate pruritus, due to atopic dermatitis (eczema) or lichen simplex chronicus AND the following: 1. Inadequate response, intolerance or contraindication to ONE medication in EACH of the following categories: a. Topical antihistamine (see Appendix I) b. High potency topical corticosteroid (see Appendix II) 2. Physician agrees to taper patient’s dose to the FDA recommended dose, and after tapered will only use for short-term pruritus relief (up to 8 days) a. Patients using over 60 grams of topical doxepin in 90 days be required to taper to 60 grams topical doxepin within 90 days Prior - Approval Limits Quantity 180 grams for 90 days Duration 3 months ___________________________________________________________________ Prior – Approval Renewal Requirements None (see appendix below) Doxepin 5% cream FEP Clinical Rationale DOXEPIN CREAM 5% (Prudoxin, Zonalon) APPENDIX I Drug Dosage Form Diphenhydramine Cream Phenyltoloxamine Lotion/ Cream Tripelennamine Cream Phendiamine Cream APPENDIX II Relative Potency of Selected Topical Corticosteroid Drug ProductsDosage Form Strength I. Very high potency Augmented betamethasone Ointment, Gel 0.05% dipropionate Clobetasol propionate Cream, Ointment 0.05% Diflorasone diacetate Ointment 0.05% Halobetasol propionate Cream, Ointment 0.05% II. High potency Amcinonide Cream, Lotion, 0.1% Augmented betamethasone Cream,Ointment Lotion 0.05% dipropionate Betamethasone Cream, Ointment 0.05% Betamethasonedipropionate valerate Ointment 0.1% Desoximetasone Cream, Ointment 0.25% Gel 0.05% Diflorasone diacetate Cream, Ointment 0.05% (emollient base) Fluocinonide Cream, Ointment, Gel 0.05% Halcinonide Cream, Ointment 0.1% Triamcinolone acetonide Cream, Ointment 0.5% III.