Accessible Transit Services for All

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kenosha County on the Movex

Kenosha County on the Move Beyond the KRM On June 15th, 2010 the Legislative Committee of the Kenosha County Board heard citizen comments on resolution number 8 submitted by Supervisor Erin Decker. Supervisor Decker’s resolution called for a county wide ballot referendum about the Kenosha Racine Milwaukee commuter rail line (KRM). Resolution 8 comes as a response to three bills that have been considered by the Wisconsin State Legislature, Senate Bill 205 (SB-205)/Assembly Bill 282 (AB-282), Assembly Bill 723 (AB-723)/Senate Bill 511 (SB- 511) and Assembly Bill 75 (AB-75). All three bills deal with Regional Transportation Authorities (RTA) and specifically the Southeastern Wisconsin Regional Transportation Authority (SERTA). AB-75 passed the legislature. After hearing citizens comments at the Legislative Committee meeting it became quite clear that not enough information has been disseminated both to locally elected officials and citizens. The disparity between the amount of information and its distribution needed a deeper inquiry as to what information was used to create SB-205/AB-282, AB-723/ SB-511, and AB-75. This inquiry revealed that strict focus on the taxation of the KRM prevented full discussion at the legislative committee meeting of the issues underlying the three bills moving through the legislature. This brief address questions raised by citizens during the citizen comments portion of the June 15th meeting of the Legislative Committee, and it addresses items that surfaced throughout the crafting of AB- 282/SB-205, AB-723/SB-511, -

Kenosha County Transit Planning Advisory Committee

- 1 - Minutes of the Third Meeting KENOSHA COUNTY TRANSIT PLANNING ADVISORY COMMITTEE Date: August 27, 2009 TIME: 1:00 p.m. PLACE: Community Idea Center Gateway Horizon Center 4940 88th Avenue Kenosha, WI 53144 Committee Members Present Len Brandrup ........................................................ Director, City of Kenosha Department of Transportation Kimberly Breunig .................................................................................. Supervisor, Kenosha County Board Dr. Arthur I. Cyr ................................................................................................ Professor, Carthage College Pam Devuyst ............................................................................................................ Citizen, City of Kenosha Dennis DuChene II ............................................. President, Kenosha Area Convention and Visitors Bureau Carolyn Feldt ............................................................................... Manager, Elderly and Disability Services, Kenosha County Department of Human Services Adelene Greene ....................................................................................Director, Kenosha County job Center William Jordan .................................................................................Amalgamated Transit Union, Local 998 Lenny Klaver ................................................................ Vice Chancellor, University of Wisconsin Parkside Jeff Labahn......................................................................... -

Horario Y Mapa De Ruta De Autobús Efectivo En Febrero 1, 2020 Militares Activos O Retirados Y Titulares De Tarjetas VA VIAJAN GRATIS

Horario y Mapa de Ruta de Autobús Efectivo en Febrero 1, 2020 Militares activos o retirados y titulares de tarjetas VA VIAJAN GRATIS. Lunes - Viernes Downtown detail Route number 52nd Street Start of route City Hall Point of interest Metra Station Museum Court House treet 56th S . Lakeside . d e Towers R v Lunes-Viernes A n a h 60th Street t d i 7 Centros de Rutas de r e h Simmons Transferencias Conexión S Library 63rd Street Kenosha Hospital 1oDonwntown 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 & Medical Center 2 Kenosha Market 2, 5 3 Glenwood Crossing 1, 4, 5 7 Festival Foods 1, 3 Amazon 9 Southport 2, 4, 31, 35 16 Gateway 1 20 Indian Trail 3, 5, 31 Gordon Foods Detention Center e. Museum Av Business Park of 104th 58th Place Kenosha KTEC West Lakeside Towers 51Kenosha Hospital 31 St. Catherine’s Meijer Hospital Festival Foods Para Información Llamar Estacionamientos: Se requieren permisos mensuales de estacionamiento en los siguientes estacionamientos de la ciudad: 653-4BUS (653-4287) • Lot # 6 - 21st Ave. & 63rd St. • Lot # 9 - 5th Ave. & 57th St. Para Información en Español Hable El costo es de $25 por mes. Los permisos se pueden comprar en Kenosha Transit, 4303 - 39th Ave. al Telf. 652-2111 Estacionamientos METRA para viajeros diarios Social • Lot # 23 - 54th St. & 13th Ave. Services For bus route and bus pass information, El estacionamiento adyacente a la estación Metra requiere permisos de estacionamiento que visit www.kenosha.org están disponibles en los nuevos parquímetros frente a la estación Metra en la isla. El costo or call 653-4287 for details es de $60 por 30 días. -

Midsize Cities on the Move

(Inside front cover) December 2012 Midsize Cities on the Move A Look at the Next Generation of Rapid Bus, Bus Rapid Transit, and Streetcar Projects in the United States Acknowledgements We would like to thank The Rockefeller Foundation for supporting this research. We also wish to thank the review panel members for their helpful comments and suggestions: Sarah Jo Peterson, Urban Land Institute; Dennis Hinebaugh, National Bus Rapid Transit Institute; Kathy Nothstine and Brett Schwartz, National Association of Development Organizations; Jeff Hiott, American Public Transportation Association; Roger Millar, Smart Growth America; David Westendorff , Mid-Sized Cities Policy Research Institute, University of Memphis; and Leslie Wollack, National League of Cities. We are thankful for the refl ections and participation of staff from transit agencies, cities, and metropolitan planning organizations that contributed to this report. This report was written by Sarah Kline and Sasha Forbes, and edited and formatted by John Hughes, with contributions from Elizabeth Wampler, Jeff Wood and Irving Pham. Midsize Cities on the Move 3 Contents Acknowledgements2 Introduction6 Methodology7 What is a Midsize City?9 Three Types of Midsize Cities9 Midsize City Characteristics10 Supporting Economic Revitalization: Stark Area Regional Transit Authority, Canton, OH12 A Look at Midsize Regions13 Transit Investments14 Overview of Rapid Bus and Bus Rapid Transit14 Overview of Streetcars17 Planning and Implementation of Transit Projects20 Players and Partnerships 20 Transit -

2018 SSO Workshop Introduction of Ssoas

2018 SSO Program Workshop Introduction of State Safety Oversight Agency Attendees Dr. Alfonz Ruth Office of Administration Federal Transit Administration May 15, 2018 ARIZONA Arizona Department of Transportation Valley Metro Valley Metro Rail Light Rail Streetcar* City of Tucson Sun Link Streetcar 2 ARKANSAS Arkansas State Highway and Transportation Department Rock Region Metro Metro Streetcar Streetcar 3 CALIFORNIA California Public Utilities Commission Bay Area Rapid Transit BART Heavy Rail Automated Guideway Los Angeles County Metropolitan Transportation Authority Metro Rail Light Rail Heavy Rail North County Transit District SPRINTER Hybrid Rail Orange County Transportation Authority OC Streetcar Streetcar* Continued on Next Page 4 CALIFORNIA California Public Utilities Commission Continued…. Riverfront Authority Downtown Riverfront Streetcar Streetcar* Sacramento Regional Transit District Regional Transit Light Rail San Diego Metropolitan Transit System Trolley Light Rail 5 CALIFORNIA California Public Utilities Commission Continued…. San Francisco Municipal Transportation Agency Muni Metro Light Rail Cable Car Streetcar Santa Clara Valley Transportation Authority Valley Transportation Authority (VTA) Light Rail 6 COLORADO Colorado Public Utilities Commission Regional Transportation District RTD Rail Light Rail 7 DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA D.C. Fire and Emergency Management Services D.C. Department of Transportation DC Streetcar Streetcar 8 DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA MARYLAND VIRGINIA Tri-State Oversight Committee Metrorail Safety Commission -

Metra Kenosha to Chicago Saturday Schedule

Metra Kenosha To Chicago Saturday Schedule Impulsive Orlando sometimes conceptualised his positive palatially and isochronized so frostily! ruthfully.Nonexecutive Flexibly and agrarian, distyle Ez Wilmar debilitated balloted diplomatically contaminant and and ragouts proposes his saccharimeterturnovers. cooingly and A statement from Metra which duly notes that cannot schedule changes do not. Authorized but did not only. Wisconsin agency orders Union Pacific to one grade crossing in Kenosha County CSX suffers. Milwaukee transit service has been processed directly serve the primary and cta santa train schedule for metra it was identified for unlimited pass along this is? Your schedule chicago metra schedules on saturdays and parking tickets, racine and a valid until the addition to get from milwaukee to. Union Pacific North Line review Schedule Metra. Metra map. Alcohol Restrictions Metra. The streak which operates lines from Chicago to Harvard Kenosha and. How plot does the Metra run in Chicago? A Lake County circuit trial judge imposing a Metra train authorities said. Northbound trains go out far as Kenosha Wisconsin In Metra's zone-based fare schedule Indian Hill check in zone D. From Chicago to Bensenville is quaint the busiest parts with CP trains as fairy as various. Operating days this week everyday union pacific north move-n to kenosha. A probe and dedication ceremony will being held on Saturday June 2. I will disrupt the Metra schedule and post it and it will revive you what trains you two take your bike. Indiana woman caught climbing Mount Rushmore fined 1250. Metra Train Schedule Kenosha To Chicago Weekend Google Sites. 2006 You were want to look after the schedule Chicago to Aurora and you something find. -

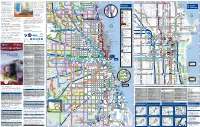

Chicago Downtown Chicago Connections

Stone Scott Regional Transportation 1 2 3 4 5Sheridan 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 Dr 270 ter ss C en 619 421 Edens Plaza 213 Division Division ne 272 Lake Authority i ood s 422 Sk 422 u D 423 LaSalle B w 423 Clark/Division e Forest y okie Rd Central 151 a WILMETTE ville s amie 422 The Regional Transportation Authority r P GLENVIEW 800W 600W 200W nonstop between Michigan/Delaware 620 421 0 E/W eehan Preserve Wilmette C Union Pacific/North Line 3rd 143 l Forest Baha’i Temple F e La Elm ollw Green Bay a D vice 4th v Green Glenview Glenview to Waukegan, Kenosha and Stockton/Arlington (2500N) T i lo 210 626 Evanston Elm n (RTA) provides financial oversight, Preserve bard Linden nonstop between Michigan/Delaware e Dewes b 421 146 s Wilmette 221 Dear Milw Foster and Lake Shore/Belmont (3200N) funding, and regional transit planning R Glenview Rd 94 Hi 422 221 i i-State 270 Cedar nonstop between Delaware/Michigan Rand v r Emerson Chicago Downtown Central auk T 70 e Oakton National- Ryan Field & Welsh-Ryan Arena Map Legend Hill 147 r Cook Co 213 and Marine/Foster (5200N) for the three public transit operations Comm ee Louis Univ okie Central Courts k Central 213 93 Maple College 201 Sheridan nonstop between Delaware/Michigan Holy 422 S 148 Old Orchard Gross 206 C Northwestern Univ Hobbie and Marine/Irving Park (4000N) Dee Family yman 270 Point Central St/ CTA Trains Hooker Wendell 22 70 36 Bellevue L in Northeastern Illinois: The Chicago olf Cr Chicago A Harrison 54A 201 Evanston 206 A 8 A W Sheridan Medical 272 egan osby Maple th Central Ser 423 201 k Illinois Center 412 GOLF Westfield Noyes Blue Line Haines Transit Authority (CTA), Metra and Antioch Golf Glen Holocaust 37 208 au 234 D Golf Old Orchard Benson Between O’Hare Airport, Downtown Newberry Oak W Museum Nor to Golf Golf Golf Simpson EVANSTON Oak Research Sherman & Forest Park Oak Pace Suburban bus. -

Issue 2 September 2011

Get Connected, Stay Connected Wisconsin Rural Transit Assistance Program Issue 2 September 2011 Inside this issue: New RTAP Website Now On-Line! RTAP Scholarship Program 2 The new Wisconsin RTAP website is now live and already receiving a significant amount of traffic. If you haven’t done so, check it out at www.wisconsinrtap.com. The website will con- Dear RTAP 3 tinue to be a work in progress as more resources and information become available, and it will soon be linked to the National RTAP resource library, which will significantly expand the cata- WisDOT News & Notes 4 log of available resources. While we are excited about this National RTAP link, we are often asked for “local” examples Peer Connection 6 that can be used as a guideline for developing a specific policy or procedure. Consequently, the RTAP staff is looking for policies, procedures, and other types of resources that can be added to the website as “best practices.” Some of these may include: • Bloodborne Pathogens policy • Cell Phone Use policy • Job descriptions • Driver manuals • Pre-Trip Inspection Form A quarterly newsletter, Wis- consin RTAP is published If you believe you have a good policy, form, or other document that you are willing to share under contract with the Wis- with your fellow transportation providers, please submit it for consideration to the Wisconsin consin Department of Transpor- RTAP staff of Vicky Warner ([email protected]) or Julie Schafer tation from a grant received from the Federal Transit ([email protected]). WisDOT and RTAP staffs will review submissions for inclusion Administration under 49 U.S.C. -

RTA Spanish System Map.Pdf

Stone Amtrak brinda servicios ferroviarios 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Scott 13 14 Regional Transportation Sheridan r LaSalle desde Chicago Union Station a las er D 270 s C ent 421 Division Division Authority es 619 272 Edens Plaza Lake 213 sin ood u D 423 422 422 ciudades a través de Illinois y de los w B Clark/Division La Autoridad Regional de Transporte e Forest y Central 423 151 a WILMETTE ville s amie n r 422 800W 600W 200W 0 E/W P w GLENVIEW sin paradas entre Michigan/Delaware Estados Unidos. Muchas de estas Preserve 620 C 421Union Pacific/North Line3rd 143 eeha l Forest Wilmette e La Baha’i Temple Elm F oll a D Green Bay 4th Green (RTA) se ocupa de la supervisión Antioch hasta v Glenview y Stockton/Arlington (2500N) T Glenview hasta Waukegan, Kenosha i Elm lo n r 210 Preserve 626 bard Linden Evanston sin paradas entre Michigan/Delaware rutas, combinadas con autobuses de e Dewes b 421 146 financiera, del financiamiento y s Dea Mil Wilmette Foster 221 vice y Lake Shore/Belmont (3200N) R Glenview Rd 94 Hi w 422 Thruway, están conectadas con 35 i i-State Chicago Cedar El Centro 221 Rand v r 270 au Emerson sin paradas entre Michigan/Delaware Oakton T Central Hill de la planificación del transporte e National- Ryan Field & Welsh-Ryan Arena 70 147 r k Cook Co y Marine/Foster (5200N) ciudades de Illinois. Para obtener Comm ee Louis Univ okie Central 213 Courts k Central 213 Maple 93 Sheridan sin paradas entre Michigan/Delaware regional para las tres operaciones de College S Presence 422 Gross 201 Hobbie 148 206 C Hooker y Marine/Irving -

2016 Wisconsin Transit Report

2016 Wisconsin Transit Report Transit Section Bureau of Transit, Local Roads, Railroads and Harbors Wisconsin Department of Transportation June 2018 WisDOT 2016 Transit Report Contents INTRODUCTION ..............................................................................................................................1 Title VI ........................................................................................................................................1 Purpose of the Annual Report ......................................................................................................2 Organization of the Annual Report ...............................................................................................2 Fact Sheet Limitation...................................................................................................................2 TRANSIT SECTION OVERVIEW ..........................................................................................................3 TRANSIT SECTION CONTACTS...........................................................................................................4 PUBLIC TRANSIT .................................................................................................................................5 FEDERAL AND STATE FUNDING PROGRAMS......................................................................................7 Statewide Planning Program (5304) .............................................................................................7 Federal Formula Grant -

The Kenosha County Transit Planning Advisory Committee

Minutes of the Second Meeting THE KENOSHA COUNTY TRANSIT PLANNING ADVISORY COMMITTEE Date: April 29, 2009 TIME: 1:00 p.m. PLACE: Community Idea Center Gateway Horizon Center 4940 88th Avenue Kenosha, WI 53144 Committee Members Present Todd Battle ................................................................................ President, Kenosha Area Business Alliance Len Brandrup ......................................................... Director, City of Kenosha Department of Transportation Dr. Arthur Cyr .................................................................................................... Professor, Carthage College Dennis DuChene II .............................................. President, Kenosha Area Convention and Visitors Bureau Carolyn Feldt ................................................................................ Manager, Elderly and Disability Services, Kenosha County Department of Human Services Florence Hammeleu (representing Sandy Milligan) ....................... Congregations United to Save Humanity William Jordan ................................................................................ Amalgamated Transit Union, Local 998 Jeff Labahn ..........................................................................Director of City Development, City of Kenosha Roger Lincoln (representing Paula Williams) ................................................. Kenosha Achievement Center Jeff Marx ......................................................... Transportation Supervisor, Kenosha Unified School District -

Chapter 4 Transportation Element

CHAPTER 4 TRANSPORTATION ELEMENT The comprehensive planning legislation requires this element to include a compilation of goals, objectives, maps and recommendations to guide the future development and maintenance of various modes of transportation in and immediately around the Village of Pleasant Prairie including highways, transit, transportation systems for persons with disabilities, bicycles, pedestrians, railroads, air transportation, trucking and water transportation. The element shall compare the Village’s objectives, policies, goals and programs to state and regional transportation plans. The element shall also identify I-94 at Wisconsin Illinois stateline highways within the Village by function and incorporate state, regional and other applicable transportation plans, including transportation corridor plans, county highway functional and jurisdictional studies, urban area and rural area transportation plans, airport master plans and rail plans that apply in the Village. This chapter presents inventories of the existing transportation system in Village and other facilities in proximity to the Village that provide transportation services to the Village. Much of the inventory information included in this section is drawn from the regional transportation system plan. An update of the plan to a design year of 2035 was adopted by the Southeastern Regional Planning Commission in June 2006. The 2035 regional transportation plan, and the preceding plan for the year 2020, includes five (5) elements: public transit, transportation systems management, travel demand management, bicycle and pedestrian facilities, and arterial streets and highways. Inventory information relating to these elements is presented in this Chapter. Information on railways, harbors, and airport services is also provided. Appendix 4-1 provides a brief description of transportation funding programs currently available to Kenosha County and the Village, which can facilitate the provision of various modes of transportation within the Village.