The Ocean Last Night - an Exegesis & Creative Artefact

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Critical Review of Russula Species (Agaricomycetes) Known from Tatra National Park (Poland and Slovakia)

Polish Botanical Journal 54(1): 41–53, 2009 CRITICAL REVIEW OF RUSSULA SPECIES (AGARICOMYCETES) KNOWN FROM TATRA NATIONAL PARK (POLAND AND SLOVAKIA) ANNA RONIKIER & SLAVOMÍR ADAMČÍK Abstract. All available published data on the occurrence of Russula species in Tatra National Park are summarized. Excluding the doubtful data, which are discussed herein, 66 species are recognized in Tatra National Park. Within each of the three main geomorphological units of the range, 42 species were recorded in the West Tatras, 18 in the High Tatras, and 16 in the Belanské Tatry Mts; additionally, 35 species were found in areas outside the Tatra Mts but within the National Park borders. Montane forests are the richest in Russula species (58); 13 species were found in the subalpine and 8 in the alpine belt. The number of reported species is highest in the Polish part of the West Tatra Mts; almost no data are available from the Slovak High Tatras. The smallest unit, the Belanské Tatry Mts, is the Tatra region best studied for alpine species. In comparison to other regions in Poland and Slovakia, Tatra National Park seems to be relatively well investigated, but in view of the richness of habitats in the Tatra Mts, we believe the actual diversity of Russula species in the region is higher than presently known. Key words: Russula, fungi, biodiversity, Slovakia, Poland, mountains, altitudinal zones Anna Ronikier, Department of Mycology, W. Szafer Institute of Botany, Polish Academy of Sciences, Lubicz 46, PL-31-512 Kraków, Poland; e-mail: [email protected] Slavomír Adamčík, Institute of Botany, Slovak Academy of Sciences, Dúbravská cesta 14, SK-845 23 Bratislava, Slovakia; e-mail: [email protected] INTRODUCTION The genus Russula is among most diverse genera partners of arctic-alpine dwarf shrubs (Kühner of Agaricomycetes. -

Russulas of Southern Vancouver Island Coastal Forests

Russulas of Southern Vancouver Island Coastal Forests Volume 1 by Christine Roberts B.Sc. University of Lancaster, 1991 M.S. Oregon State University, 1994 A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in the Department of Biology © Christine Roberts 2007 University of Victoria All rights reserved. This dissertation may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopying or other means, without the permission of the author. Library and Bibliotheque et 1*1 Archives Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de I'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A0N4 Ottawa ON K1A0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-47323-8 Our file Notre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-47323-8 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives and Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par Plntemet, prefer, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans loan, distribute and sell theses le monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, worldwide, for commercial or non sur support microforme, papier, electronique commercial purposes, in microform, et/ou autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriete du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in et des droits moraux qui protege cette these. -

Key to Alberta Edible Mushrooms Note: Key Should Be Used With"Mushrooms of Western Canada"

Key to Alberta Edible Mushrooms Note: Key should be used with"Mushrooms of Western Canada". The key is designed to help narrow the field of possibilities. Should never be used without more detailed descriptions provided in field guides. Always confirm your choice with a good field guide. Go A Has pores or sponge like tubes on underside 2 to 1 Go B Does not have visible pores or sponge like tubes 22 to Leatiporus sulphureous A Bright yellow top, brighter pore surface, shelf like growth on wood "Chicken of the woods" 2 Go B not as above with pores or sponge like tubes 3 to Go A Has sponge like tube layer easily separated from cap 4 to 3 B Has shallow pore layer not easily separated from cap Not described in this key A Medium to large brown cap, thick stalk, fine embossed netting on stalk Boletus edulis 4 Go B Not as above with sponge like tube layer 5 to A Dull brown to beige cap, fine embossed netting on stalk Not described in this key 5 Go B Not as above with sponge like tube layer 6 to Go A Dry cap, rough ornamented stem, with flesh staining various shades of pink to gray 7 to 6 Go B Not as above 12 to Go A Cap orange to red, never brown or white 8 to 7 Go B Cap various shades of dark or light brown to beige/white 10 to A Dark orangey red cap, velvety cap surface, growing exclusively with conifers Leccinum fibrilosum 8 Go B Orangey cap, growing in mixed or pure aspen poplar stands 9 to Orangey - red cap, skin flaps on cap margins, slowly staining pinkish gray, earliest of the leccinums starting A Leccinum boreale in June. -

Rockland Gazette

The Rockland Gazette. Gazette Job Printing PUBLISHED EVERY THURSDAY AFTERNOON bY ESTABLISHMENT. VOSE & PORTEH, Having every facility in Presses, Type and MatosW- to which we are constantly maHng aiddltlooa, wa ara 2 I O M a in S tre e t. piepared to execute with promptness and goad styla every variety of Job Printing, ineladta* Town Reports, Catalogues, TERMS: Posters, Shop B ills, Hand B ills, Pro If paid strictly in advance—per annum, $2.00. If payment is delayed 6 mouths, 2.25. grammes, Circulars, Bill Heads, If not paid till the close of the year, 2.60. Letter Heads, Law and Corpor <8i“ Newsuhscribeifl areexpected to make the first ation Blanks, Receipts, Bills payment in advance. of Lading, Business, Ad paper will bo discontinued until ALL Alt- dress and Wedding ■ Earues are paid, unless at the option of the publish ers. Cards, Tags, x* dingle copies live cents—for sale nt the office and Labels, at the Bookstores. VOLUME 35. ROCKLAND, MAINE, THURSDAY, MARCH 18, 1880. &c.9 Z. POPE VOSE. J. B. PORTER. NO. 16. PRINTING IN COLORS AND BRONZINO will receive prompt attention. harvests of heaven will never become such carrjed her into the house and there lenrned derness was like that of a mother. “ God “ I thought I’d tell ye, gentleman, the ns shespoke.and I promised. Her “ friend ” deserts hut some good seed will tako root all. Both had been deceived. sent von to me. For her sake this shall mistress is justcomin’. ’ The saints purtect therein.” —I would have promised her anything for POND’S It was a terrible scene tlie old front room he your home. -

80130Dimou7-107Weblist Changed

Posted June, 2008. Summary published in Mycotaxon 104: 39–42. 2008. Mycodiversity studies in selected ecosystems of Greece: IV. Macrofungi from Abies cephalonica forests and other intermixed tree species (Oxya Mt., central Greece) 1 2 1 D.M. DIMOU *, G.I. ZERVAKIS & E. POLEMIS * [email protected] 1Agricultural University of Athens, Lab. of General & Agricultural Microbiology, Iera Odos 75, GR-11855 Athens, Greece 2 [email protected] National Agricultural Research Foundation, Institute of Environmental Biotechnology, Lakonikis 87, GR-24100 Kalamata, Greece Abstract — In the course of a nine-year inventory in Mt. Oxya (central Greece) fir forests, a total of 358 taxa of macromycetes, belonging in 149 genera, have been recorded. Ninety eight taxa constitute new records, and five of them are first reports for the respective genera (Athelopsis, Crustoderma, Lentaria, Protodontia, Urnula). One hundred and one records for habitat/host/substrate are new for Greece, while some of these associations are reported for the first time in literature. Key words — biodiversity, macromycetes, fir, Mediterranean region, mushrooms Introduction The mycobiota of Greece was until recently poorly investigated since very few mycologists were active in the fields of fungal biodiversity, taxonomy and systematic. Until the end of ’90s, less than 1.000 species of macromycetes occurring in Greece had been reported by Greek and foreign researchers. Practically no collaboration existed between the scientific community and the rather few amateurs, who were active in this domain, and thus useful information that could be accumulated remained unexploited. Until then, published data were fragmentary in spatial, temporal and ecological terms. The authors introduced a different concept in their methodology, which was based on a long-term investigation of selected ecosystems and monitoring-inventorying of macrofungi throughout the year and for a period of usually 5-8 years. -

MUSHROOMS of the OTTAWA NATIONAL FOREST Compiled By

MUSHROOMS OF THE OTTAWA NATIONAL FOREST Compiled by Dana L. Richter, School of Forest Resources and Environmental Science, Michigan Technological University, Houghton, MI for Ottawa National Forest, Ironwood, MI March, 2011 Introduction There are many thousands of fungi in the Ottawa National Forest filling every possible niche imaginable. A remarkable feature of the fungi is that they are ubiquitous! The mushroom is the large spore-producing structure made by certain fungi. Only a relatively small number of all the fungi in the Ottawa forest ecosystem make mushrooms. Some are distinctive and easily identifiable, while others are cryptic and require microscopic and chemical analyses to accurately name. This is a list of some of the most common and obvious mushrooms that can be found in the Ottawa National Forest, including a few that are uncommon or relatively rare. The mushrooms considered here are within the phyla Ascomycetes – the morel and cup fungi, and Basidiomycetes – the toadstool and shelf-like fungi. There are perhaps 2000 to 3000 mushrooms in the Ottawa, and this is simply a guess, since many species have yet to be discovered or named. This number is based on lists of fungi compiled in areas such as the Huron Mountains of northern Michigan (Richter 2008) and in the state of Wisconsin (Parker 2006). The list contains 227 species from several authoritative sources and from the author’s experience teaching, studying and collecting mushrooms in the northern Great Lakes States for the past thirty years. Although comments on edibility of certain species are given, the author neither endorses nor encourages the eating of wild mushrooms except with extreme caution and with the awareness that some mushrooms may cause life-threatening illness or even death. -

Mycorrhizal Fungi of Aspen Forests: Natural Occurrence and Potential Applications

Utah State University DigitalCommons@USU Aspen Bibliography Aspen Research 2001 Mycorrhizal fungi of aspen forests: natural occurrence and potential applications C.L. Cripps Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/aspen_bib Part of the Forest Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Cripps, CL. 2001. Mycorrhizal fungi of aspen forests: natural occurrence and potential applications. WD Shepperd et al (compilers). Sustaining Aspen in Western Landscapes: Symposium Proceedings. Proceedings RMRS-P-18. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station. Fort Collins, CO. This Contribution to Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Aspen Research at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Aspen Bibliography by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Mycorrhizal Fungi of Aspen Forests: Natural Occurrence and Potential Applications Cathy L. Cripps1 Abstract—Native mycorrhizal fungi associated with aspen were surveyed on three soil types in the north-central Rocky Mountains. Selected isolates were tested for the ability to enhance aspen seedling growth in vitro. Over 50 species of ectomycorrhizal fungi occur with Populus tremuloides in this region, primarily basidiomycete fungi in the Agaricales. Almost one-third (30%) were ubiquitous with aspen and were found on all three soil types. Over one-third (37%) were restricted to the acidic, sandy soil of the smelter-impacted Butte-Anaconda area, revealing a subset of fungi that tolerate these conditions. Mycorrhizal fungi were screened for their ability to enhance aspen growth and establishment. Of nine selected isolates, all but one increased the biomass of aspen seedlings 2–4 times. -

Mushrooms Traded As Food

TemaNord 2012:542 TemaNord Ved Stranden 18 DK-1061 Copenhagen K www.norden.org Mushrooms traded as food Nordic questionnaire, including guidance list on edible mushrooms suitable Mushrooms traded as food and not suitable for marketing. For industry, trade and food inspection Mushrooms recognised as edible have been collected and cultivated for many years. In the Nordic countries, the interest for eating mushrooms has increased. In order to ensure that Nordic consumers will be supplied with safe and well characterised, edible mushrooms on the market, this publication aims at providing tools for the in-house control of actors producing and trading mushroom products. The report is divided into two documents: a. Volume I: “Mushrooms traded as food - Nordic questionnaire and guidance list for edible mushrooms suitable for commercial marketing b. Volume II: Background information, with general information in section 1 and in section 2, risk assessments of more than 100 mushroom species All mushrooms on the lists have been risk assessed regarding their safe use as food, in particular focusing on their potential content of inherent toxicants. The goal is food safety. Oyster Mushroom (Pleurotus ostreatus) TemaNord 2012:542 ISBN 978-92-893-2382-6 http://dx.doi.org/10.6027/TN2012-542 TN2012542 omslag ENG.indd 1 11-07-2012 08:00:29 Mushrooms traded as food Nordic questionnaire, including guidance list on edible mushrooms suitable and not suitable for marketing. For industry, trade and food inspection Jørn Gry (consultant), Denmark, Christer Andersson, -

Pine Cove Market &

Real POSTMASTER: Dated material, please deliver March 14-16, 2012 Estate See page 15. Idyllwild News bites Crime Local pleads guilty to burglary. TCoveringo the Sanw Jacinto and Santan Rosa Moun tainsC from Twinr Pinesı to Anzaer to Pinyon See page 2 Almost all the News — Part of the Time Daylight Saving Time The view from Idyllwild VOL. 67 NO. 11 75¢ (Tax Included) IDYLLWILD, CA THURS., MARCH 15, 2012 Arts students. See page 4. Smart Meters Sheriff to discuss SoCal Edison proposed opt-out plan. See page 8. local crime Jail grants By Marshall Smith Staff Reporter Riverside County County gets $100 million Sheriff’s meeting to expand jails. he recent escalation on local crime See page 9. in criminal activity Tin the Idyllwild area, 2 p.m. Saturday, Sports! including an armed rob- March 24 Champs crowned at end bery and a growing number of volleyball and basketball of felony property crimes, Idyllwild School seasons. has prompted the Riverside Gymnasium See pages 10 and 11. County Sheriff’s Depart- ment to call a community Lilacs meeting in Idyllwild. Cap- crime, the role and use of The strategy for a future tain Scot Collins, Hemet Sta- the Mountain Community tion Commander and staff spring festival. Patrol, and what community will meet with Hill com- members can do to protect See page 14. On Saturday, this male bald eagle graced the skies over Lake Hemet while humans munity members at a town their homes and neigh- counted the eagles for the Forest Service. Photo by Careena Chase meeting at the Idyllwild borhoods. -

Family Latin Name Notes Agaricaceae Agaricus Californicus Possible; No

This Provisional List of Terrestrial Fungi of Big Creek Reserve is taken is taken from : (GH) Hoffman, Gretchen 1983 "A Preliminary Survey of the Species of Fungi of the Landels-Hill Big Creek Reserve", unpublished manuscript Environmental Field Program, University of California, Santa Cruz Santa Cruz note that this preliminary list is incomplete, nomenclature has not been checked or updated, and there may have been errors in identification. Many species' identifications are based on one specimen only, and should be considered provisional and subject to further verification. family latin name notes Agaricaceae Agaricus californicus possible; no specimens collected Agaricaceae Agaricus campestris a specimen in grassland soils Agaricaceae Agaricus hondensis possible; no spcimens collected Agaricaceae Agaricus silvicola group several in disturbed grassland soils Agaricaceae Agaricus subrufescens one specimen in oak woodland roadcut soil Agaricaceae Agaricus subrutilescens Two specimenns in pine-manzanita woodland Agaricaceae Agaricus arvensis or crocodillinus One specimen in grassland soil Agaricaceae Agaricus sp. (cupreobrunues?) One specimen in grassland soil Agaricaceae Agaricus sp. (meleagris?) Three specimens in tanoak duff of pine-manzanita woodland Agaricaceae Agaricus spp. Other species in soiils of woodland and grassland Amanitaceae Amanita calyptrata calyptroderma One specimen in mycorrhizal association with live oak in live oak woodland Amanitaceae Amanita chlorinosa Two specimens in mixed hardwood forest soils Amanitaceae Amanita fulva One specimen in soil of pine-manzanita woodland Amanitaceae Amanita gemmata One specimen in soil of mixed hardwood forest Amanitaceae Amanita pantherina One specimen in humus under Monterey Pine Amanitaceae Amanita vaginata One specimen in humus of mixed hardwood forest Amanitaceae Amanita velosa Two specimens in mycorrhizal association with live oak in oak woodland area Bolbitiaceae Agrocybe sp. -

Oolhopt Fiaturalists' Jielb (Club. Have Been Missed

o • • TRANSACTIONS OF THE WOOLHOPE NATURALISTS' FIELD CLUB. [ESTABLISHED 1851.] 1905, 1906, 1907. " HOPE ON." " HOPE EVER." HEREFORD: PRINTED BY JAKEMAN AND CARVER. ISSUED APRIL, 1911. EDITOR'S PREFACE. Owing to various circumstances the issue of the present Volume of Transactions has been unavoidably delayed, much to the regret of the Editorial Committee. The death of the late accomplished Editor, Dr. Cecil Moore, deprived the Club of the services of one whose long experience and extensive acquaintance with the subjects which engage the interests of its members made him a difficult man to follow, and some time elapsed before arrangements could be made to take up his work. A great quantity of matter, manuscript and printed, had accumulated in Dr. Moore's hands, and at his death was deposited in the Woolhope Library. To sift and prepare for the press what Dr. Moore had intended for publication has been necessarily a work of time, but it is hoped that the Volume now in the hands of members will justify the delay in publication, and prove not altogether unworthy of its predecessors. Owing to the size of the present Volume several interesting papers are held over to the next Volume. For the carefully prepared Index to the Volume the Club is indebted to Mr. Sledmere. V. TRANSACTIONS FOR THE YEARS 1905, 1906, 1907. TABLE OF CONTENTS. Editor's Preface Table of Contents .. Titles of Papers and Contributions .. Illustrations, Diagrams, Tables, &c. Officers for 1905, 1906, 1907 Presidents of the Club since 1851 List of Honorary Members .. Corresponding Societies List of Ordinary Members . -

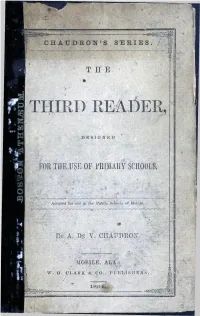

For the Use of Primary Schools

—— -----------------*----------- -— 1 I CHAUDRON’S SERIES. / i THE THIRD 1> E S I G N K D FOR THE USE OF PRIMARY SCHOOLS, /*V Adopted tor me in tlie Public Schools? o f Mohije. r>Y A. Dp Y. CriAIWvOX. MOBILE, ALA.: I W. G. CL A K 1C &. CO., PUBLISHERS. \ H- ■B CHALDRON’S SERIES THE THIRD READER, DESIGNED FOR THE USE OF PRIMARY SCHOOLS, Adopted for ic Schools o f Mobile. - o O o--r j < > . \ V By A. B e T . CHAUDRON. 0 \ MOBILE, ALA.: W . Q . CLARK & CO., PUBLISHERS. n f t 1 8 0 4 . .“3 Entered according to the Act o f Congress, in the year 1864, by A . D e V. CH AU DRON, in the Clerk's Office o f the C. S. District Court o f the Southern Division of the District of Alabama. j b 7 * ' p t N A j ■ , r T CO* ■ r* J w J * CONTENTS. TAGE. Child’s Prayer. ■ Part First. LESSON. PAGE. 1 Punctuation................................................................................................ 9 2 Elementary E x ercise s..........................................................................12 3 Rich and Poor ......................................................... ............................ 1^ •1 Hugh and Ellen......................................................................................... 16 5 Albert’s Pony ................... .......................... ...................... ...................... 18 6 I will be good to-day.................................................................................20 7 Mary's Ilome..............................................................................................21 8 God sees us................................................