Clinical Approach to Peripheral Neuropathy: Anatomic Localization and Diagnostic Testing

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dental Plexopathy Vesta Guzeviciene, Ricardas Kubilius, Gintautas Sabalys

SCIENTIFIC ARTICLES Stomatologija, Baltic Dental and Maxillofacial Journal, 5:44-47, 2003 Dental Plexopathy Vesta Guzeviciene, Ricardas Kubilius, Gintautas Sabalys SUMMARY Aim and purpose of the study were: 1) to study and compare unfavorable factors playing role in the development of upper teeth plexitis and upper teeth plexopathy; 2) to study peculiarities of clinical manifestation of upper teeth plexitis and upper teeth plexopathy, and to establish their diagnostic value; 3) to optimize the treatment. The results of examination and treatment of 79 patients with upper teeth plexitis (UTP-is) and 63 patients with upper teeth plexopathy (UTP-ty) are described in the article. Questions of the etiology, pathogenesis and differential diagnosis are discussed, methods of complex medicamental and surgical treatment are presented. Keywords: atypical facial neuralgia, atypical odontalgia, atypical facial pain, vascular toothache. PREFACE Besides the common clinical tests, in order to ana- lyze in detail the etiology and pathogenesis of the afore- Usually the injury of the trigeminal nerve is re- mentioned disease, its clinical manifestation and pecu- lated to the pathology of the teeth neural plexuses. liarities, we performed specific examinations such as According to the literature data, injury of the upper orthopantomography of the infraorbital canals, mea- teeth neural plexuses makes more than 7% of all sured the velocity of blood flow in the infraorbital blood neurostomatologic diseases. Many terms are used in vessels (doplerography), examined the pain threshold literature to characterize the clinical symptoms com- of facial skin and oral mucous membrane in acute pe- plex of the above-mentioned pathology. Some authors riod and remission, and evaluated the role that the state (1, 2, 3) named it dental plexalgia or dental plexitis. -

Brachial-Plexopathy.Pdf

Brachial Plexopathy, an overview Learning Objectives: The brachial plexus is the network of nerves that originate from cervical and upper thoracic nerve roots and eventually terminate as the named nerves that innervate the muscles and skin of the arm. Brachial plexopathies are not common in most practices, but a detailed knowledge of this plexus is important for distinguishing between brachial plexopathies, radiculopathies and mononeuropathies. It is impossible to write a paper on brachial plexopathies without addressing cervical radiculopathies and root avulsions as well. In this paper will review brachial plexus anatomy, clinical features of brachial plexopathies, differential diagnosis, specific nerve conduction techniques, appropriate protocols and case studies. The reader will gain insight to this uncommon nerve problem as well as the importance of the nerve conduction studies used to confirm the diagnosis of plexopathies. Anatomy of the Brachial Plexus: To assess the brachial plexus by localizing the lesion at the correct level, as well as the severity of the injury requires knowledge of the anatomy. An injury involves any condition that impairs the function of the brachial plexus. The plexus is derived of five roots, three trunks, two divisions, three cords, and five branches/nerves. Spinal roots join to form the spinal nerve. There are dorsal and ventral roots that emerge and carry motor and sensory fibers. Motor (efferent) carries messages from the brain and spinal cord to the peripheral nerves. This Dorsal Root Sensory (afferent) carries messages from the peripheral to the Ganglion is why spinal cord or both. A small ganglion containing cell bodies of sensory NCS’s sensory fibers lies on each posterior root. -

Anatomical, Clinical, and Electrodiagnostic Features of Radial Neuropathies

Anatomical, Clinical, and Electrodiagnostic Features of Radial Neuropathies a, b Leo H. Wang, MD, PhD *, Michael D. Weiss, MD KEYWORDS Radial Posterior interosseous Neuropathy Electrodiagnostic study KEY POINTS The radial nerve subserves the extensor compartment of the arm. Radial nerve lesions are common because of the length and winding course of the nerve. The radial nerve is in direct contact with bone at the midpoint and distal third of the humerus, and therefore most vulnerable to compression or contusion from fractures. Electrodiagnostic studies are useful to localize and characterize the injury as axonal or demyelinating. Radial neuropathies at the midhumeral shaft tend to have good prognosis. INTRODUCTION The radial nerve is the principal nerve in the upper extremity that subserves the extensor compartments of the arm. It has a long and winding course rendering it vulnerable to injury. Radial neuropathies are commonly a consequence of acute trau- matic injury and only rarely caused by entrapment in the absence of such an injury. This article reviews the anatomy of the radial nerve, common sites of injury and their presentation, and the electrodiagnostic approach to localizing the lesion. ANATOMY OF THE RADIAL NERVE Course of the Radial Nerve The radial nerve subserves the extensors of the arms and fingers and the sensory nerves of the extensor surface of the arm.1–3 Because it serves the sensory and motor Disclosures: Dr Wang has no relevant disclosures. Dr Weiss is a consultant for CSL-Behring and a speaker for Grifols Inc. and Walgreens. He has research support from the Northeast ALS Consortium and ALS Therapy Alliance. -

New Insights in Lumbosacral Plexopathy

New Insights in Lumbosacral Plexopathy Kerry H. Levin, MD Gérard Said, MD, FRCP P. James B. Dyck, MD Suraj A. Muley, MD Kurt A. Jaeckle, MD 2006 COURSE C AANEM 53rd Annual Meeting Washington, DC Copyright © October 2006 American Association of Neuromuscular & Electrodiagnostic Medicine 2621 Superior Drive NW Rochester, MN 55901 PRINTED BY JOHNSON PRINTING COMPANY, INC. C-ii New Insights in Lumbosacral Plexopathy Faculty Kerry H. Levin, MD P. James. B. Dyck, MD Vice-Chairman Associate Professor Department of Neurology Department of Neurology Head Mayo Clinic Section of Neuromuscular Disease/Electromyography Rochester, Minnesota Cleveland Clinic Dr. Dyck received his medical degree from the University of Minnesota Cleveland, Ohio School of Medicine, performed an internship at Virginia Mason Hospital Dr. Levin received his bachelor of arts degree and his medical degree from in Seattle, Washington, and a residency at Barnes Hospital and Washington Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, Maryland. He then performed University in Saint Louis, Missouri. He then performed fellowships at a residency in internal medicine at the University of Chicago Hospitals, the Mayo Clinic in peripheral nerve and electromyography. He is cur- where he later became the chief resident in neurology. He is currently Vice- rently Associate Professor of Neurology at the Mayo Clinic. Dr. Dyck is chairman of the Department of Neurology and Head of the Section of a member of several professional societies, including the AANEM, the Neuromuscular Disease/Electromyography at Cleveland Clinic. Dr. Levin American Academy of Neurology, the Peripheral Nerve Society, and the is also a professor of medicine at the Cleveland Clinic College of Medicine American Neurological Association. -

Novel Pathomechanisms in Inflammatory Neuropathies David Schafflick1, Bernd C

Schafflick et al. Journal of Neuroinflammation (2017) 14:232 DOI 10.1186/s12974-017-1001-8 REVIEW Open Access Novel pathomechanisms in inflammatory neuropathies David Schafflick1, Bernd C. Kieseier2, Heinz Wiendl1 and Gerd Meyer zu Horste1* Abstract Inflammatory neuropathies are rare autoimmune-mediated disorders affecting the peripheral nervous system. Considerable progress has recently been made in understanding pathomechanisms of these disorders which will be essential for developing novel diagnostic and therapeutic strategies in the future. Here, we summarize our current understanding of antigenic targets and the relevance of new immunological concepts for inflammatory neuropathies. In addition, we provide an overview of available animal models of acute and chronic variants and how new diagnostic tools such as magnetic resonance imaging and novel therapeutic candidates will benefit patients with inflammatory neuropathies in the future. This review thus illustrates the gap between pre-clinical and clinical findings and aims to outline future directions of development. Keywords: Experimental autoimmune neuritis, Guillain-Barré syndrome, Chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy, Animal model, Th17 cells Background between 0.8 and 1.9 per 100,000 worldwide. Men are Inflammatory neuropathies are a heterogeneous group of approximately 1.5-fold more frequently affected and the autoimmune disorders affecting the peripheral nervous incidence increases with age [6]. Although the majority of system (PNS) that can exhibit an acute or chronic disease patients recover, the prognosis can remain poor with severe course. They are rare, but cause significant and often per- disability or death in 9–17% of all GBS patients [7]. In many manent disability in many affected patients [1, 2]. -

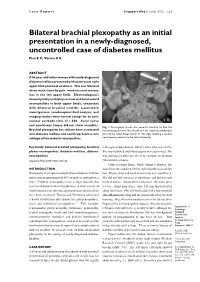

Bilateral Brachial Plexopathy As an Initial Presentation in a Newly-Diagnosed, Uncontrolled Case of Diabetes Mellitus Pica E C, Verma K K

Case Report Singapore Med J 2008; 49(2) : e29 Bilateral brachial plexopathy as an initial presentation in a newly-diagnosed, uncontrolled case of diabetes mellitus Pica E C, Verma K K ABSTRACT A 55-year-old Indian woman with newly-diagnosed diabetes mellitus presented with acute onset right upper limb proximal weakness. This was followed three weeks later by pain, weakness and sensory loss in the left upper limb. Electrodiagnosis showed patchy multiple proximal and distal axonal neuropathies in both upper limbs, consistent with bilateral brachial neuritis. Laboratory investigations, cerebrospinal fluid analysis, and imaging studies were normal except for an anti- nuclear antibody titre of 1:640. Sural nerve and quadriceps biopsy did not show vasculitis. Fig. 1 Photograph shows the patient’s inability to flex the Brachial plexopathy has seldom been associated interphalangeal joint of the thumb and the distal interphalangeal with diabetes mellitus and could represent a rare joint of the index finger (pinch or OK sign) implying a median subtype of the diabetic neuropathies. nerve lesion proximal to the wrist bilaterally. Keywords: bilateral brachial plexopathy, brachial with signs of dehydration. HbA1c at the time was 14.2%. plexus neuropathies, diabetes mellitus, diabetic She was hydrated and blood sugars were optimised. She neuropathies was discharged after one week to continue medication Singapore Med J 2008; 49(2): e29-e32 (Metformin) at home. Upon reaching home, while taking a shower, she INTRODUCTION found that she could not lift her right shoulder to wash her Neuropathy is a frequent complication of diabetes mellitus hair. Elbow, wrist and hand movements were unaffected. -

Brachial Plexopathy Following High-Dose Melphalan and Autologous Peripheral Blood Stem Cell Transplantation

Bone Marrow Transplantation (2010) 45, 951–952 & 2010 Macmillan Publishers Limited All rights reserved 0268-3369/10 $32.00 www.nature.com/bmt LETTER TO THE EDITOR Brachial plexopathy following high-dose melphalan and autologous peripheral blood stem cell transplantation Bone Marrow Transplantation (2010) 45, 951–952; Tone and power were normal throughout, lower limb deep doi:10.1038/bmt.2009.243; published online 21 September 2009 tendon reflexes were absent and plantars were downgoing. Magnetic resonance imaging of the whole spine at this point revealed widespread myelomatous involvement of the Neuromuscular pathologies are a recognized complication bony spine but no cord compromise. Thalidomide was of SCT, often occurring as a result of infection or continued with no alteration in dosage. The patient haemorrhage, but also in association with GVHD follow- subsequently underwent a PBSCT with high-dose melpha- ing allogeneic SCT.1 The published literature on post- lan as the conditioning regime. transplant peripheral nervous system pathologies includes Within 14 days of stem-cell infusion the patient devel- descriptions of myasthenia gravis, Guillain-Barre´ oped progressive proximal weakness affecting predomi- syndrome, polymyositis and peripheral neuropathy.2–5 nantly the upper limbs. There was no neck pain or Ocular toxicity, radiculopathy and plexopathy have also involvement of bladder or bowel. Examination revealed rarely been reported. We report three cases of brachial bilateral wrist-drop with grade 3–4 weakness of the small plexopathy occurring after autologous peripheral blood muscles of the hand, elbow flexors and extensors and stem cell transplantation (PBSCT). shoulder abduction. Upper limb reflexes were absent. The neurological findings in the lower limbs were unchanged. -

Electrodiagnosis of Brachial Plexopathies and Proximal Upper Extremity Neuropathies

Electrodiagnosis of Brachial Plexopathies and Proximal Upper Extremity Neuropathies Zachary Simmons, MD* KEYWORDS Brachial plexus Brachial plexopathy Axillary nerve Musculocutaneous nerve Suprascapular nerve Nerve conduction studies Electromyography KEY POINTS The brachial plexus provides all motor and sensory innervation of the upper extremity. The plexus is usually derived from the C5 through T1 anterior primary rami, which divide in various ways to form the upper, middle, and lower trunks; the lateral, posterior, and medial cords; and multiple terminal branches. Traction is the most common cause of brachial plexopathy, although compression, lacer- ations, ischemia, neoplasms, radiation, thoracic outlet syndrome, and neuralgic amyotro- phy may all produce brachial plexus lesions. Upper extremity mononeuropathies affecting the musculocutaneous, axillary, and supra- scapular motor nerves and the medial and lateral antebrachial cutaneous sensory nerves often occur in the context of more widespread brachial plexus damage, often from trauma or neuralgic amyotrophy but may occur in isolation. Extensive electrodiagnostic testing often is needed to properly localize lesions of the brachial plexus, frequently requiring testing of sensory nerves, which are not commonly used in the assessment of other types of lesions. INTRODUCTION Few anatomic structures are as daunting to medical students, residents, and prac- ticing physicians as the brachial plexus. Yet, detailed understanding of brachial plexus anatomy is central to electrodiagnosis because of the plexus’ role in supplying all motor and sensory innervation of the upper extremity and shoulder girdle. There also are several proximal upper extremity nerves, derived from the brachial plexus, Conflicts of Interest: None. Neuromuscular Program and ALS Center, Penn State Hershey Medical Center, Penn State College of Medicine, PA, USA * Department of Neurology, Penn State Hershey Medical Center, EC 037 30 Hope Drive, PO Box 859, Hershey, PA 17033. -

Painful Brachial Plexopathy: an Unusual Presentation of Polyarteritis Nodosa S

Postgrad Med J: first published as 10.1136/pgmj.58.679.311 on 1 May 1982. Downloaded from Postgraduate Medical Journal (May 1982) 58, 311-313 Painful brachial plexopathy: an unusual presentation of polyarteritis nodosa S. G. ALLAN* H. M. A. TOWLA* M.R.C.P. B. Med. Biol., M.B. C. C. SMITH* A. W. DOWNIE* F.R.C.P. F.R.C.P. J. C. CLARKt M.B., Ch.B. *Department ofMedicine, The Royal Infirmary, Foresterhill, Aberdeen tDepartment ofPathology, University ofAberdeen, Foresterhill Summary intact save for evidence of a right recurrent laryn- An elderly man was admitted to hospital with an geal nerve palsy on indirect laryngoscopy. There unusual painful bilateral brachial neuropathy, which was a flicker of left biceps contraction and grade 2/5 progressed in spite ofhigh dose corticosteroid therapy. power in the deltoids and adductors of the shoulders, Polyarteritis nodosa, characterized by widespread but otherwise total paralysis of the upper limbs. arteriolar involvement, was shown at post-mortem. Marked tenderness was noted over each brachial copyright. plexus, but there was neither muscle tenderness nor fasciculation. 'Glove' loss of all sensory modalities Introduction was present up to the elbows bilaterally, with hypo- The clinical presentations of polyarteritis nodosa tonicity and areflexia. There was minimal hip flexor are classically diverse, reflecting variable vascular weakness and absent left knee and both ankle involvement of many organs and tissues. Mono- reflexes without sensory abnormality or calf tender- neuritis multiplex is the most common neurological ness. Bladder and bowel functions were unaffected sequel (Ford and Siekert, 1965), but asymmetrical and examination otherwise unremarkable. -

Neuromuscular Ultrasound of Cranial Nerves

JCN Open Access REVIEW pISSN 1738-6586 / eISSN 2005-5013 / J Clin Neurol 2015;11(2):109-121 / http://dx.doi.org/10.3988/jcn.2015.11.2.109 Neuromuscular Ultrasound of Cranial Nerves Eman A. Tawfika b Ultrasound of cranial nerves is a novel subdomain of neuromuscular ultrasound (NMUS) Francis O. Walker b which may provide additional value in the assessment of cranial nerves in different neuro- Michael S. Cartwright muscular disorders. Whilst NMUS of peripheral nerves has been studied, NMUS of cranial a Department of Physical Medicine nerves is considered in its initial stage of research, thus, there is a need to summarize the re- and Rehabilitation, search results achieved to date. Detailed scanning protocols, which assist in mastery of the Faculty of Medicine, techniques, are briefly mentioned in the few reference textbooks available in the field. This re- Ain Shams University, view article focuses on ultrasound scanning techniques of the 4 accessible cranial nerves: op- Cairo, Egypt bDepartment of Neurology, tic, facial, vagus and spinal accessory nerves. The relevant literatures and potential future ap- Medical Center Boulevard, plications are discussed. Wake Forest University School of Medicine, Key Wordszz neuromuscular ultrasound, cranial nerve, optic, facial, vagus, spinal accessory. Winston-Salem, NC, USA INTRODUCTION Neuromuscular ultrasound (NMUS) refers to the use of high resolution ultrasound of nerve and muscle to assess primary neuromuscular disorders. Beginning with a few small studies in the 1980s, it has evolved into a growing subspecialty area of clinical and re- search investigation. Over the last decade, electrodiagnostic laboratories throughout the world have adopted the technique because of its value in peripheral entrapment and trau- matic neuropathies. -

CUBITAL TUNNEL SYNDROME I. Background the Ulnar Nerve

CUBITAL TUNNEL SYNDROME I. Background The ulnar nerve originates from the C8 and T1 spinal nerve roots and is the terminal branch of the medial cord of the brachial plexus. The ulnar nerve travels posterior to the medial epicondyle of the humerus at the elbow and enters the cubital tunnel. After exiting the cubital tunnel, the ulnar nerve passes between the humeral and ulnar heads of the flexor carpi ulnaris muscle and continues distally to innervate the intrinsic hand musculature. Ulnar nerve compression occurs most commonly at the elbow. At the elbow, ulnar nerve compression has been reported at five sites: the arcade of Struthers, medial intermuscular septum, medial epicondyle/post-condylar groove, cubital tunnel and deep flexor pronator aponeurosis. The most common site of entrapment is at the cubital tunnel. Ulnar nerve compression at the elbow may have multiple causes, including: A. chronic compression B. local edema or inflammation C. space-occupying lesion such as a tumor or bone spur D. repetitive elbow flexion and extension E. prolonged flexion of the elbow, as an habitual sleeping in the fetal position F. in association with a metabolic disorder including diabetes mellitus. Ulnar neuropathy at the elbow can occur at any demographic but is generally seen between 25 and 45 years of age and occurs slightly more often in women than in men. II. Diagnostic Criteria A. Pertinent History and Physical Findings Patients often present with intermittent paresthesias, numbness and/or tingling in the small finger and ulnar half of the ring finger (i.e. ulnar nerve distribution). These symptoms may be more prominent after prolonged periods of elbow flexion, such as sleeping in the “fetal position”, sleeping with the arm tucked under the pillow or head, or with repetitive elbow flexion-extension activities. -

Inflammation and Neuropathic Attacks in Hereditary Brachial Plexus Neuropathy C J Klein,Pjbdyck, S M Friedenberg, T M Burns, a J Windebank, P J Dyck

45 J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry: first published as 10.1136/jnnp.73.1.45 on 1 July 2002. Downloaded from PAPER Inflammation and neuropathic attacks in hereditary brachial plexus neuropathy C J Klein,PJBDyck, S M Friedenberg, T M Burns, A J Windebank, P J Dyck ............................................................................................................................. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2002;73:45–50 Objective: To study the role of mechanical, infectious, and inflammatory factors inducing neuropathic attacks in hereditary brachial plexus neuropathy (HBPN), an autosomal dominant disorder character- ised by attacks of pain and weakness, atrophy, and sensory alterations of the shoulder girdle and upper limb muscles. Methods: Four patients from separate kindreds with HBPN were evaluated. Upper extremity nerve See end of article for biopsies were obtained during attacks from a person of each kindred. In situ hybridisation for common authors’ affiliations viruses in nerve tissue and genetic testing for a hereditary tendency to pressure palsies (HNPP; tomacu- ....................... lous neuropathy) were undertaken. Two patients treated with intravenous methyl prednisolone had Correspondence to: serial clinical and electrophysiological examinations. One patient was followed prospectively through Dr Christopher J Klein, pregnancy and during the development of a stereotypic attack after elective caesarean delivery. Mayo Clinic, 200 First Results: Upper extremity nerve biopsies in two patients showed prominent perivascular inflammatory Street SW, Rochester, infiltrates with vessel wall disruption. Nerve in situ hybridisation for viruses was negative. There were Minnesota 55905, USA; no tomaculous nerve changes. In two patients intravenous methyl prednisolone ameliorated symptoms [email protected] (largely pain), but with tapering of steroid dose, signs and symptoms worsened. Elective caesarean Received delivery did not prevent a typical postpartum attack.