1 Lecture Notes Jhumpa Lahiri (Born 1967) • “Once in a Lifetime” (2006

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bhagat Singh, and Shivaram Rajguru, Whose Conspiracy Led to the Assassination of Deputy Superintendent of Police, J

SWAPNIL SANSAR, ENGLISH WEEKLY,LUCKNOW, 21,MARCH, (07) Sukhdev Thapar, Freeom Fighter Sukhdev Thapar was an revolutionary. He was a senior member of Hindustan in New Delhi (8th April 1929), Sukhdev and his accomplices have been arrest - Socialist Republican Association. He was hanged on 23 March1931 at the age ed and convicted of their crime, going through the loss of life sentence as the of 23.Sukhdev Thapar, born (15 May 1907) in Ludhiana, Punjab, British India to verdict. On twenty-third March 1931, the 3 courageous revolutionaries, Bhagat Ramlal Thapar and Ralli Devi. Sukhdev's father died and he was brought up by Singh, Sukhdev Thapar and Shivaram Rajguru have been hanged, at the same his uncle Lala Achintram.Sukhdev Thapar was a member of the Hindustan time as their bodies were secretly cremated at the banks of the River Sutlej. Socialist Republican Association (HSRA), and organised revolutionary cells in Sukhdev Thapar turned into just 24 years vintage whilst he became a martyr for Punjab and other areas of North India.Sukhdev is best remembered for his his motherland, however, he will usually be remembered for his courage, patri - involvement in the Lahore Conspiracy Case of 18 December 1928 and its after - otism, and sacrifice of his existence for India's independence. Agency. math. He was an accomplice of Bhagat Singh, and Shivaram Rajguru, whose conspiracy led to the assassination of Deputy Superintendent of Police, J. P. Shivaram Hari Rajguru Saunders in 1928 in response to the vio - Shivaram Hari Rajguru was an revolutionary from Maharashtra, known mainly lent death of a veteran leader,On 23 March for his involvement in the assassination of a British Raj police officer.Rajguru 1931, the three men were hanged. -

My Art Educations: Learning to Embrace the Dialogism in a Lifetime of Teaching and Learning Experiences. DISSERTATION Presented

My Art Educations: Learning to Embrace the Dialogism in a Lifetime of Teaching and Learning Experiences. DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Andrew Lawrence Moffatt Graduate Program in Arts Administration, Education and Policy The Ohio State University 2018 Dissertation Committee: Dr. Shari Savage, advisor Dr. Deborah Smith-Shank Dr. Joni Boyd Acuff Copyrighted by Andrew Lawrence Moffatt 2018 Abstract The goal of this autoethnographic narrative inquiry is to develop a pragmatic theory of dialogism, liminality, and hybridity that applies to art educators reflecting the following questions: How can graduate school and a teaching practice interact dialogically? How can the liminal spaces between graduate school (theory) and art teaching (practice) be more productive? How can an art teacher thrive as a hybrid of teacher/learner? I identify instances of dialogic co- constructed knowledge but monologic or dialectic experiences have been more prevalent. By interpreting and analyzing my art educations a theory is developed to optimize educational interaction to enhance learning experiences of teachers, and consequently learning experiences of their students. ii Acknowledgments Many educators have taught and inspired me through the four degrees I have earned from The Ohio State University. The university educators make up one half of the equation that is my art education. The other half is my colleagues from public education. Some of these people guided and/or taught alongside me for decades. Together these two communities have greatly influenced the experiences upon which this dissertation is based, and I thank them for working with me. -

201208 August IMDA

August 1 Irish Music & 2012 Dance Association Lúnasa 30th Year, Issue No. 8 The mission of the Irish Music and Dance Association is to support, coordinate, encourage and promote high quality activities and programs in Irish music, dance, and other cultural traditions within the community and to insure the continuation of those traditions. New Offerings at Irish Fair Inside this issue: Irish Fair has several new things to check out this year: Tune of the Month 2 The overall layout of the festival grounds will be changing in 2012. The new Gaelic Corner 3 Céilíúradh Céim (Celebration Stage) replaces the River Stage and will be located IMDA Grant Winner 7 on the west end of the grounds. The Cultural Area will be moving to a new site along the river, with a new layout for the Triscéil Tea Room and some new exhibits August Calendar 10-11 will provide visitors with background on the contributions of the Irish to Minnesota. Northwoods Songs 16 And the Crossroad Dance Hall and Children’s Area will be also be located along Ceili Corner 18 the river. Smidirini 19 The Atlantic Steps , an international-touring adaptation of the phenomenally successful Irish show Fuaim Chonamara, will be presented on Saturday evening. It tells the epic story of Ireland’s oldest dance form, portrayed through the music, song, dance and energy of the Connemara region. Centered around the joyful dance and unbridled enthusiasm of Brian Cunningham, the show continues to move festival and theatre audiences to their feet, bringing sean-nós dance to its rightful place on the world stage. -

Nationalism in India Lesson

DC-1 SEM-2 Paper: Nationalism in India Lesson: Beginning of constitutionalism in India Lesson Developer: Anushka Singh Research scholar, Political Science, University of Delhi 1 Institute of Lifelog learning, University of Delhi Content: Introducing the chapter What is the idea of constitutionalism A brief history of the idea in the West and its introduction in the colony The early nationalists and Indian Councils Act of 1861 and 1892 More promises and fewer deliveries: Government of India Acts, 1909 and 1919 Post 1919 developments and India’s first attempt at constitution writing Government of India Act 1935 and the building blocks to a future constitution The road leading to the transfer of power The theory of constitutionalism at work Conclusion 2 Institute of Lifelog learning, University of Delhi Introduction: The idea of constitutionalism is part of the basic idea of liberalism based on the notion of individual’s right to liberty. Along with other liberal notions,constitutionalism also travelled to India through British colonialism. However, on the one hand, the ideology of liberalism guaranteed the liberal rightsbut one the other hand it denied the same basic right to the colony. The justification to why an advanced liberal nation like England must colonize the ‘not yet’ liberal nation like India was also found within the ideology of liberalism itself. The rationale was that British colonialism in India was like a ‘civilization mission’ to train the colony how to tread the path of liberty.1 However, soon the English educated Indian intellectual class realised the gap between the claim that British Rule made and the oppressive and exploitative reality of colonialism.Consequently,there started the movement towards autonomy and self-governance by Indians. -

Hungry Bengal: War, Famine, Riots, and the End of Empire 1939-1946

Hungry Bengal: War, Famine, Riots, and the End of Empire 1939-1946 By Janam Mukherjee A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Anthropology and History) In the University of Michigan 2011 Doctoral Committee: Professor Barbara D. Metcalf, Chair Emeritus Professor David W. Cohen Associate Professor Stuart Kirsch Associate Professor Christi Merrill 1 "Unknown to me the wounds of the famine of 1943, the barbarities of war, the horror of the communal riots of 1946 were impinging on my style and engraving themselves on it, till there came a time when whatever I did, whether it was chiseling a piece of wood, or burning metal with acid to create a gaping hole, or cutting and tearing with no premeditated design, it would throw up innumerable wounds, bodying forth a single theme - the figures of the deprived, the destitute and the abandoned converging on us from all directions. The first chalk marks of famine that had passed from the fingers to engrave themselves on the heart persist indelibly." 2 Somnath Hore 1 Somnath Hore. "The Holocaust." Sculpture. Indian Writing, October 3, 2006. Web (http://indianwriting.blogsome.com/2006/10/03/somnath-hore/) accessed 04/19/2011. 2 Quoted in N. Sarkar, p. 32 © Janam S. Mukherjee 2011 To my father ii Acknowledgements I would like to thank first and foremost my father, Dr. Kalinath Mukherjee, without whom this work would not have been written. This project began, in fact, as a collaborative effort, which is how it also comes to conclusion. His always gentle, thoughtful and brilliant spirit has been guiding this work since his death in May of 2002 - and this is still our work. -

Downloaded 2021-09-27T03:18:32Z

Provided by the author(s) and University College Dublin Library in accordance with publisher policies. Please cite the published version when available. Title The ripple that drowns? Twentieth-century famines in China and India as economic history Authors(s) Ó Gráda, Cormac Publication date 2007-11 Series UCD Centre for Economic Research Working Paper Series; WP07/19 Publisher University College Dublin; Centre for Economic Research Link to online version http://www.ucd.ie/economics/research/papers/2007/WP07.19.pdf Item record/more information http://hdl.handle.net/10197/473 Downloaded 2021-09-27T03:18:32Z The UCD community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters! (@ucd_oa) © Some rights reserved. For more information, please see the item record link above. UCD CENTRE FOR ECONOMIC RESEARCH WORKING PAPER SERIES 2007 The Ripple that Drowns? Twentieth-century famines in China and India as economic history Cormac Ó Gráda, University College Dublin WP07/19 November 2007 UCD SCHOOL OF ECONOMICS UNIVERSITY COLLEGE DUBLIN BELFIELD DUBLIN 4 THE RIPPLE THAT DROWNS? TWENTIETH-CENTURY FAMINES IN CHINA AND INDIA AS ECONOMIC HISTORY Cormac Ó Gráda University College, Dublin I. Introduction Major famines are rare today, and tend to be ‘man-made’. Where crop failure is the main threat, as in southern Africa in 2002 and Niger in 2005, a combination of public action, market forces, and food aid tends to mitigate excess mortality. Although non- crisis death rates in sub-Saharan Africa remain high, excess mortality from famine in 2002 and 2005 was miniscule. The twentieth century saw the virtual elimination of famines caused simply by crop failures. -

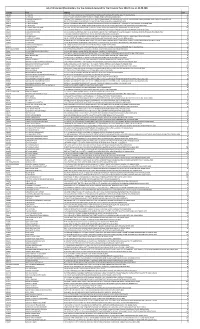

For the Dividend Declared for the Financial Year 2012-13 As on 12.09.2017

List of Unclaimed Shareholders: For the dividend declared for the Financial Year 2012-13 as on 12.09.2017 FOLIO NO NAME ADDRESS AMT A04314 A B FONTES 104 IVTH CROSS KALASIPALYAM NEW EXTENSION BANGALORE BANGALORE,KARNATAKA,PIN-560002,INDIA 25 A17671 A C SRAJAN 66 LUZ CHURCH ROAD MYLAPORE CHENNAI CHENNAI,TAMIL NADU,PIN-600004,INDIA 180 D00252 A DHAKSHINAMOORTHY PARTNER V M C TRADERS STOCKISTS OF A C LTD 6/10 MARIAMMAN KOIL RAMANATHAPURAM DT RAMANATHAPURAM RAMNAD,TAMIL NADU,PIN-623501,INDIA 90 A02076 A JANARDHAN 8/1101 SESHAGIRINIVAS NEW ROAD COCHIN COCHIN ERNAKULAM,KERALA,PIN-682002,INDIA 25 A02270 A K BHATTACHARYA UNITED COMMERCIAL BANK MATA ANANDA NAGAR SHIVALA HOSPITAL VARANASI U P VARANASI,UTTAR PRADESH,PIN-221001,INDIA 25 A03705 A K NARAYANA C/O A K KESAUACHAR 451 TENTH CROSS GIRINAGAR SECOND PHASE BANGALORE BANGALORE,KARNATAKA,PIN-560085,INDIA 25 P00351 A K RAMACHANDRAPRABHU 'PAVITRA' NO 949 24TH MAIN ROAD J P NAGAR II PHASE BANGALORE BANGALORE,KARNATAKA,PIN-560078,INDIA 360 A17411 A KALPAKAM NARAYAN C/O V KAMESWARARAO 7-6-108 ENUGULAMALAL STREET SRIKAKULAM (A.P.) SRIKAKULAM,ANDHRA PRADESH,PIN-532001,INDIA 18 A03555 A LAKSHMINARAYANA C/O G ARUNACHALAM RANA PLOT NO 30 LEPAKSHI COLONY WEST MARREDPALLY SECUNDERABAD HYDERABAD,ANDHRA PRADESH,PIN-500026,INDIA 25 A04366 A M DAVID 1 MISSION COMPOUND AJMER ROAD JAIPUR JAIPUR,RAJASTHAN,PIN-302006,INDIA 25 M00394 A MURUGESAN 3 A D BLOCK V G RAO NAGAR EXTENSION KATPADI P O VELLORE N A A DT VELLORE NORTH ARCOT,TAMIL NADU,PIN-632007,INDIA 23 A17672 A N VENKATALAKSHMI 361 XI A CROSS 29TH MAIN J -

Discover Boyne Valley 2019 Birthplace of Ireland’S Ancient East

FREE HOLIDAY GUIDE & MAP Discover Boyne Valley 2019 Birthplace of Ireland’s Ancient East discoverboynevalley.ie “The Boyne is not a showy river. It rises in County Kildare and flows gently and majestically through County Meath and joins the sea at Drogheda in County Louth some 112 kilometres later. It has none of the razzmatazz of its sister, the Shannon. It’s neither the longest river in Ireland, nor does it have the greatest flow. What is does have, and by the gallon, is history. In fact, the Boyne Valley is like a time capsule. Travel along it and you travel through millennia of Irish history, from passage tombs that pre-date the Pyramids, to the Hill of Tara, seat of the High Kings of Ireland, all the way to the home of the First World War poet Francis Ledwidge in Slane. It’s the Irish equivalent of Egypt’s Valley of the Kings. And you can choose to explore it by car, bicycle, kayak, or by strolling along its banks and the towpaths of the navigation canals that run alongside from Navan to Oldbridge.” Frances Power - Editor, Cara, the Aer Lingus inflight magazine - Boyne Valley Feature, October/November 2014 Pg 68-78 Cara magazine is available online at issuu.com discoverboynevalley.ie Contents The Boyne River 01 Fleadh Cheoil na hÉireann 2019 17 Towns & Villages 33 Ireland’s Ancient East 03 Spirits of Meath Halloween Festival 19 Angling 37 Discover Boyne Valley Flavours 05 Walking & Cycling 21 Horse Racing 39 Easy Access 07 Boyne Valley Gardens 23 Golf 41 Adventures & Activities 09 Boyne Valley Crafts 25 Where to Stay 43 Organised and Guided Tours 11 Where is the Boyne Valley 27 Eating Out 49 Music, Arts & Culture 13 Boyne Valley Drive 29 Pubs & Night Clubs 51 Festivals & Events 15 Boyne Valley Drive Sites 31 Craft Distilling, Brewing & Cider Making 54 Photography courtesy of: copterview.ie, tel 086 8672339; jennymatthewsphotography.com, tel 087 2451184; perfectstills.com, tel 086 1740454; and irelandscontentpool.com 01 02 the River Boyne Loughcrew To tell the story of Ireland’s Ancient East we must start at the beginning.. -

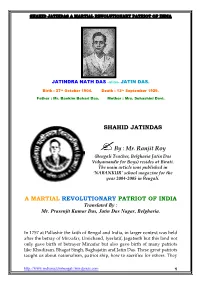

JATINDRA NATH DAS -Alias- JATIN DAS

JATINDRA NATH DAS -alias- JATIN DAS. Birth : 27 th October 1904. Death : 13 th September 1929. Father : Mr. Bankim Behari Das. Mother : Mrs. Suhashini Devi. SHAHID JATINDAS ?By : Mr. Ranjit Roy (Bengali Teacher, Belgharia Jatin Das Vidyamandir for Boys) resides at Birati. The main article was published in ‘NABANKUR’ school magazine for the year 2004-2005 in Bengali. A MARTIAL REVOLUTIONARY PATRIOT OF INDIA Translated By : Mr. Prasenjit Kumar Das, Jatin Das Nagar, Belgharia. In 1757 at Pallashir the faith of Bengal and India, in larger context was held after the betray of Mirzafar, Umichand, Iyerlatif, Jagatseth but this land not only gave birth of betrayer Mirzafar but also gave birth of many patriots like Khudiram, Bhagat Singh, Baghajatin and Jatin Das. These great patriots taught us about nationalism, patriot ship, how to sacrifice for others. They http://www.indianactsinbengali.wordpress.com 1 have tried their best to uphold the head of a unified, independent and united nation. Let us discuss about one of them, Jatin Das and his great sacrifice towards the nation. on 27 th October 1904 Jatin Das (alias Jatindra Nath Das) came to free the nation from the bondage of the British Rulers. He born at his Mother’s house at Sikdar Bagan. He was the first child of father Bankim Behari Das and mother Suhashini Devi. After birth the newborn did not cried for some time then the child cried loudly, it seems that the little one was busy in enchanting the speeches of motherland but when he saw that his motherland is crying for her bondage the little one cant stop crying. -

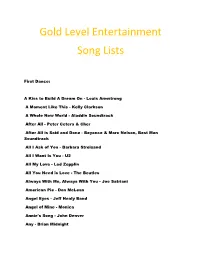

Gold Level Entertainment Song Lists

Gold Level Entertainment Song Lists First Dance: A Kiss to Build A Dream On - Louis Armstrong A Moment Like This - Kelly Clarkson A Whole New World - Aladdin Soundtrack After All - Peter Cetera & Cher After All is Said and Done - Beyonce & Marc Nelson, Best Man Soundtrack All I Ask of You - Barbara Streisand All I Want Is You - U2 All My Love - Led Zepplin All You Need is Love - The Beatles Always With Me, Always With You - Joe Satriani American Pie - Don McLean Angel Eyes - Jeff Healy Band Angel of Mine - Monica Annie's Song - John Denver Any - Brian Midnight As Long as I'm Rocking With You - John Conlee At Last - Celine Dion At Last - Etta James At My Most Beautiful - R.E.M. At Your Best - Aaliyah Battle Hymn of Love - Kathy Mattea Beautiful - Gordon Lightfoot Beautiful As U - All 4 One Beautiful Day - U2 Because I Love You - Stevie B Because You Loved me - Celine Dion Believe - Lenny Kravitz Best Day - George Strait Best In Me - Blue Better Days Ahead - Norman Brown Bitter Sweet Symphony - Verve Blackbird - The Beatles Breathe - Faith Hill Brown Eyes - Destiny's Child But I Do Love You - Leann Rimes Butterfly Kisses - Bob Carlisle By My Side - Ben Harper By Your Side - Sade Can You Feel the Love - Elton John Can't Get Enough of Your Love, Babe - Barry White Can't Help Falling in Love - Elvis Presley Can't Stop Loving You - Phil Collins Can't Take My Eyes Off of You - Frankie Valli Chapel of Love - Dixie Cups China Roses - Enya Close Your Eyes Forever - Ozzy Osbourne & Lita Ford Closer - Better than Ezra Color My World - Chicago Colour -

Table of Contents

1 •••I I Table of Contents Freebies! 3 Rock 55 New Spring Titles 3 R&B it Rap * Dance 59 Women's Spirituality * New Age 12 Gospel 60 Recovery 24 Blues 61 Women's Music *• Feminist Music 25 Jazz 62 Comedy 37 Classical 63 Ladyslipper Top 40 37 Spoken 65 African 38 Babyslipper Catalog 66 Arabic * Middle Eastern 39 "Mehn's Music' 70 Asian 39 Videos 72 Celtic * British Isles 40 Kids'Videos 76 European 43 Songbooks, Posters 77 Latin American _ 43 Jewelry, Books 78 Native American 44 Cards, T-Shirts 80 Jewish 46 Ordering Information 84 Reggae 47 Donor Discount Club 84 Country 48 Order Blank 85 Folk * Traditional 49 Artist Index 86 Art exhibit at Horace Williams House spurs bride to change reception plans By Jennifer Brett FROM OUR "CONTROVERSIAL- SUffWriter COVER ARTIST, When Julie Wyne became engaged, she and her fiance planned to hold (heir SUDIE RAKUSIN wedding reception at the historic Horace Williams House on Rosemary Street. The Sabbats Series Notecards sOk But a controversial art exhibit dis A spectacular set of 8 color notecards^^ played in the house prompted Wyne to reproductions of original oil paintings by Sudie change her plans and move the Feb. IS Rakusin. Each personifies one Sabbat and holds the reception to the Siena Hotel. symbols, phase of the moon, the feeling of the season, The exhibit, by Hillsborough artist what is growing and being harvested...against a Sudie Rakusin, includes paintings of background color of the corresponding chakra. The 8 scantily clad and bare-breasted women. Sabbats are Winter Solstice, Candelmas, Spring "I have no problem with the gallery Equinox, Beltane/May Eve, Summer Solstice, showing the paintings," Wyne told The Lammas, Autumn Equinox, and Hallomas. -

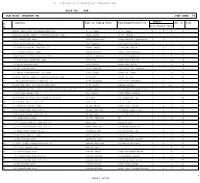

KOLKATA MC ULB CODE: 79 Ward No

BPL LIST-KOLKATA MUNICIPAL CORPORATION Ward No: 088 ULB Name :KOLKATA MC ULB CODE: 79 Member Sl Address Name of Family Head Son/Daughter/Wife of BPL ID Year No Male Female Total 1 MATHOR PARA ROAD 94 TALLYGUNGE ROAD A. P. HELA R. L. HELA 2 5 7 1 2 CHANDRA MONDAL LANE 17 CHANDRA MONDAL LANE ABHA SARKAR SUSIL SARKAR 2 1 3 2 3 100 TALLYGUNGE ROAD ACHO CHAKHALIYA LATE KRISHNA CHAKHALIYA 2 4 6 3 4 17 CHANDRA MONDAL LANE ADAR MONDAL LATE MATHUN MONDAL 0 1 1 4 5 17 CHANDRA MONDAL LANE KOL 26 ADHIR GHOSH LT AKSHAY GHOSH 2 4 6 5 6 17 CHANDRA MONDAL LANE ADHIR MONDAL LATE DURGA MONDAL 1 0 1 6 7 19A PRATAP ADITYA PLACE KOL-26 ADHIR PRAMANICK LT UPEN PRAMANICK 3 2 5 7 8 11/1/M GOPAL BANERJEE LANE AJAY DAS LATE LALIT KR.DAS 2 2 4 8 9 13 BAULI MONDAL ROAD AJAY GHOSH LATE ANIL GHOSH 3 1 4 9 10 54 TALLYGUNGE ROAD AJAY SAMANTA LATE MITHILAL SAMANTA 2 2 4 10 11 37 NEPAL BHATTACHARYA 1ST LANE AJAY SINGH LATE LOK SINGH 3 1 4 11 12 CHANDRA MONDAL LANE 17 CHANDRA MONDAL LANE AJIT DAS LT K. L. DAS 3 1 4 12 13 16A CHANDRA MONDAL LANE KOL-26 AJIT KARMAKAR LT SUDHIR KARMAKAR 4 3 7 14 14 TALLYGUNGE ROAD 108 TALLYGUNGE ROAD AJOY PRASD RAMDEB PRASAD 7 6 10+ 15 15 S.P. MUKHERJEE ROAD 200H S.P. MUKHERJEE ROAD KOL-26 ALAOK BOSE LT.