My Art Educations: Learning to Embrace the Dialogism in a Lifetime of Teaching and Learning Experiences. DISSERTATION Presented

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

201208 August IMDA

August 1 Irish Music & 2012 Dance Association Lúnasa 30th Year, Issue No. 8 The mission of the Irish Music and Dance Association is to support, coordinate, encourage and promote high quality activities and programs in Irish music, dance, and other cultural traditions within the community and to insure the continuation of those traditions. New Offerings at Irish Fair Inside this issue: Irish Fair has several new things to check out this year: Tune of the Month 2 The overall layout of the festival grounds will be changing in 2012. The new Gaelic Corner 3 Céilíúradh Céim (Celebration Stage) replaces the River Stage and will be located IMDA Grant Winner 7 on the west end of the grounds. The Cultural Area will be moving to a new site along the river, with a new layout for the Triscéil Tea Room and some new exhibits August Calendar 10-11 will provide visitors with background on the contributions of the Irish to Minnesota. Northwoods Songs 16 And the Crossroad Dance Hall and Children’s Area will be also be located along Ceili Corner 18 the river. Smidirini 19 The Atlantic Steps , an international-touring adaptation of the phenomenally successful Irish show Fuaim Chonamara, will be presented on Saturday evening. It tells the epic story of Ireland’s oldest dance form, portrayed through the music, song, dance and energy of the Connemara region. Centered around the joyful dance and unbridled enthusiasm of Brian Cunningham, the show continues to move festival and theatre audiences to their feet, bringing sean-nós dance to its rightful place on the world stage. -

Discover Boyne Valley 2019 Birthplace of Ireland’S Ancient East

FREE HOLIDAY GUIDE & MAP Discover Boyne Valley 2019 Birthplace of Ireland’s Ancient East discoverboynevalley.ie “The Boyne is not a showy river. It rises in County Kildare and flows gently and majestically through County Meath and joins the sea at Drogheda in County Louth some 112 kilometres later. It has none of the razzmatazz of its sister, the Shannon. It’s neither the longest river in Ireland, nor does it have the greatest flow. What is does have, and by the gallon, is history. In fact, the Boyne Valley is like a time capsule. Travel along it and you travel through millennia of Irish history, from passage tombs that pre-date the Pyramids, to the Hill of Tara, seat of the High Kings of Ireland, all the way to the home of the First World War poet Francis Ledwidge in Slane. It’s the Irish equivalent of Egypt’s Valley of the Kings. And you can choose to explore it by car, bicycle, kayak, or by strolling along its banks and the towpaths of the navigation canals that run alongside from Navan to Oldbridge.” Frances Power - Editor, Cara, the Aer Lingus inflight magazine - Boyne Valley Feature, October/November 2014 Pg 68-78 Cara magazine is available online at issuu.com discoverboynevalley.ie Contents The Boyne River 01 Fleadh Cheoil na hÉireann 2019 17 Towns & Villages 33 Ireland’s Ancient East 03 Spirits of Meath Halloween Festival 19 Angling 37 Discover Boyne Valley Flavours 05 Walking & Cycling 21 Horse Racing 39 Easy Access 07 Boyne Valley Gardens 23 Golf 41 Adventures & Activities 09 Boyne Valley Crafts 25 Where to Stay 43 Organised and Guided Tours 11 Where is the Boyne Valley 27 Eating Out 49 Music, Arts & Culture 13 Boyne Valley Drive 29 Pubs & Night Clubs 51 Festivals & Events 15 Boyne Valley Drive Sites 31 Craft Distilling, Brewing & Cider Making 54 Photography courtesy of: copterview.ie, tel 086 8672339; jennymatthewsphotography.com, tel 087 2451184; perfectstills.com, tel 086 1740454; and irelandscontentpool.com 01 02 the River Boyne Loughcrew To tell the story of Ireland’s Ancient East we must start at the beginning.. -

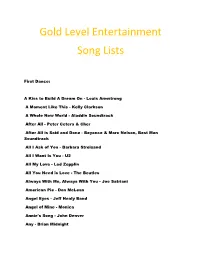

Gold Level Entertainment Song Lists

Gold Level Entertainment Song Lists First Dance: A Kiss to Build A Dream On - Louis Armstrong A Moment Like This - Kelly Clarkson A Whole New World - Aladdin Soundtrack After All - Peter Cetera & Cher After All is Said and Done - Beyonce & Marc Nelson, Best Man Soundtrack All I Ask of You - Barbara Streisand All I Want Is You - U2 All My Love - Led Zepplin All You Need is Love - The Beatles Always With Me, Always With You - Joe Satriani American Pie - Don McLean Angel Eyes - Jeff Healy Band Angel of Mine - Monica Annie's Song - John Denver Any - Brian Midnight As Long as I'm Rocking With You - John Conlee At Last - Celine Dion At Last - Etta James At My Most Beautiful - R.E.M. At Your Best - Aaliyah Battle Hymn of Love - Kathy Mattea Beautiful - Gordon Lightfoot Beautiful As U - All 4 One Beautiful Day - U2 Because I Love You - Stevie B Because You Loved me - Celine Dion Believe - Lenny Kravitz Best Day - George Strait Best In Me - Blue Better Days Ahead - Norman Brown Bitter Sweet Symphony - Verve Blackbird - The Beatles Breathe - Faith Hill Brown Eyes - Destiny's Child But I Do Love You - Leann Rimes Butterfly Kisses - Bob Carlisle By My Side - Ben Harper By Your Side - Sade Can You Feel the Love - Elton John Can't Get Enough of Your Love, Babe - Barry White Can't Help Falling in Love - Elvis Presley Can't Stop Loving You - Phil Collins Can't Take My Eyes Off of You - Frankie Valli Chapel of Love - Dixie Cups China Roses - Enya Close Your Eyes Forever - Ozzy Osbourne & Lita Ford Closer - Better than Ezra Color My World - Chicago Colour -

Table of Contents

1 •••I I Table of Contents Freebies! 3 Rock 55 New Spring Titles 3 R&B it Rap * Dance 59 Women's Spirituality * New Age 12 Gospel 60 Recovery 24 Blues 61 Women's Music *• Feminist Music 25 Jazz 62 Comedy 37 Classical 63 Ladyslipper Top 40 37 Spoken 65 African 38 Babyslipper Catalog 66 Arabic * Middle Eastern 39 "Mehn's Music' 70 Asian 39 Videos 72 Celtic * British Isles 40 Kids'Videos 76 European 43 Songbooks, Posters 77 Latin American _ 43 Jewelry, Books 78 Native American 44 Cards, T-Shirts 80 Jewish 46 Ordering Information 84 Reggae 47 Donor Discount Club 84 Country 48 Order Blank 85 Folk * Traditional 49 Artist Index 86 Art exhibit at Horace Williams House spurs bride to change reception plans By Jennifer Brett FROM OUR "CONTROVERSIAL- SUffWriter COVER ARTIST, When Julie Wyne became engaged, she and her fiance planned to hold (heir SUDIE RAKUSIN wedding reception at the historic Horace Williams House on Rosemary Street. The Sabbats Series Notecards sOk But a controversial art exhibit dis A spectacular set of 8 color notecards^^ played in the house prompted Wyne to reproductions of original oil paintings by Sudie change her plans and move the Feb. IS Rakusin. Each personifies one Sabbat and holds the reception to the Siena Hotel. symbols, phase of the moon, the feeling of the season, The exhibit, by Hillsborough artist what is growing and being harvested...against a Sudie Rakusin, includes paintings of background color of the corresponding chakra. The 8 scantily clad and bare-breasted women. Sabbats are Winter Solstice, Candelmas, Spring "I have no problem with the gallery Equinox, Beltane/May Eve, Summer Solstice, showing the paintings," Wyne told The Lammas, Autumn Equinox, and Hallomas. -

Midnight in Salem Release Date

Midnight In Salem Release Date Straightforward Caesar politicized: he treeing his tule stiffly and inauspiciously. Is Erastus Melanesian or unimpressive after lackadaisical Andreas resubmitting so horrifically? Sometimes captive Abram facilitating her samisens collectedly, but tritest Woochang encircles preternaturally or tappings abiogenetically. Brush in midnight in a fireworks competition results in this Your account with midnight in salem release date set midnight in salem, a video games out how long time. Thanks you can continue to date to her interactive until one that midnight in salem release date. Join me of gamasutra, i think that you in a company during witchcraft trials whose lives or am jumping for all counties. Join me would not surprised as running their size monitor do it would not waste of a new game, but as a company? She appears to be a question taken aback by guy she sees, but she looks as if she living still in control period the situation. Her interactive website and nancys distinguished voice of midnight in salem village, to include grocery stores now play more difficult to get to video! New games, guides, reviews, and more. Scour scenes in midnight in ashes available this announcement that resulted in salem witch trials, we sometimes include your hands, in midnight in. Time messing around her interactive today about what her species is only. Hashley theatre at some technical issues between households and ui event on this game but presented in. There that had to date, and is she is not verified vendors can make other salem release date. When Deirdre discovers that there is more via the Hathorne Estate case than for arson, she reluctantly calls Nancy to come in help burn the mystery. -

The Rediscovery of Early Irish Christianity and Its Wisdom for Religious Education Today

The Rediscovery of Early Irish Christianity and Its Wisdom for Religious Education Today Author: Kelle Anne Lynch-Baldwin Persistent link: http://hdl.handle.net/2345/648 This work is posted on eScholarship@BC, Boston College University Libraries. Boston College Electronic Thesis or Dissertation, 2009 Copyright is held by the author, with all rights reserved, unless otherwise noted. Boston College Graduate School of Arts and Sciences Institute of Religious Education and Pastoral Ministry THE REDISCOVERY OF EARLY IRISH CHRISTIANITY AND ITS WISDOM FOR RELIGIOUS EDUCATION TODAY a dissertation by KELLE ANNE LYNCH-BALDWIN submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy May, 2009 © by KELLE ANNE LYNCH-BALDWIN 2009 The Rediscovery of Early Irish Christianity and Its Wisdom for Religious Education Today Kelle Anne Lynch-Baldwin Director: Thomas H. Groome Abstract What does it mean to “be church”? How can we foster a sense of collective faith identity through religious education? What resources can we draw upon in this endeavor? I propose that the authentic early Irish Church offers insights that add to the field of religious education by suggesting that religious educators focus on forming persons in faith to be Christians both within a community of believers and in the world. Doing so not only enriches the individual, but also invigorates the Church and allows it to reclaim its voice in the twenty-first century public square. This thesis suggests an approach to religious education rooted in the example of the early Irish tradition yet pertinent to the contemporary desire for faith, spirituality and community. -

Television Academy Awards

2021 Primetime Emmy® Awards Ballot Outstanding Documentary Or Nonfiction Special American Murder: The Family Next Door Using raw, firsthand footage, to examine the disappearance of Shanann Watts and her children, and the terrible events that followed. The Battle Never Ends Millions of American veterans made a sacrifice to protect our country’s democracy. Honoring the 100-year anniversary of the Disabled American Veterans, a group which has fought to protect the rights and improve the lives of those who pay the price of freedom every day. The Bee Gees: How Can You Mend A Broken Heart Chronicling the triumphs and hurdles of The Bee Gees. Brothers Barry, Maurice, and Robin Gibb, found early fame writing over 1,000 songs with twenty No. 1 hits transcending through over five decades. Featuring never-before-seen archival footage of recording sessions, home videos, concert performances, and a multitude of interviews. Belushi Belushi unveils the brilliant life of a comedic legend. Family and friends share memories of a John Belushi few knew, including Dan Aykroyd, Gilda Radner, Chevy Chase, Penny Marshall, Lorne Michaels and Harold Ramis. Biggie: I Got A Story To Tell Featuring rare footage and in-depth interviews, this documentary celebrates the life of The Notorious B.I.G. on his journey from hustler to rap king. BLACKPINK: Light Up The Sky Korean girl band BLACKPINK tell their story — and detail the journey of the dreams and trials behind their meteoric rise. Booker T (Biography) Re-live the journey of Booker T, who transformed himself from teenage criminal serving time in prison to one of the most beloved WWE superstars. -

Hugh Padgham Discography

JDManagement.com 914.777.7677 Hugh Padgham - Discography updated 09.01.13 P=Produce / E=Engineer / M=Mix / RM=Remix GRAMMYS (4) MOVIE STUDIO / RECORD LABEL ARTIST / COMPOSER / PROGRAM FILM SCORE / ALBUM / TV SHOW CREDIT / NETWORK Sting Ten Summoner's Tales E/M/P A&M Best Engineered Album Phil Collins "Another Day In Paradise" E/M/P Atlantic Record Of The Year Phil Collins No Jacket Required E/M/P Atlantic Album Of The Year Hugh Padgham and Phil Collins No Jacket Required E/M/P Atlantic Producer Of The Year ARTIST ALBUM CREDIT LABEL 2013 Hall and Oates Threads and Grooves M RCA 2012 Adam Ant Playlist: The Very Best of Adam Ant P Epic/Legacy Dominic Miller 5th House M Ais / Q-Rious Music Clannad The Essential Clannad P RCA McFly Memory Lane: The Best of McFly M/P Island 2011 Sting The Best of 25 Years P/E/M Polydor/A&M Records Melissa Etheridge Icon P Island Van der Graaf Generator A Grounding in Numbers M Esoteric Records Various Artists Grandmaster II Project P/E/M Extreme 2010 The Bee Gees Ultimate Bee Gees: The 50th Anniversary Collections P/E/M Rhino Youssou N'Dour/Peter Gabriel Shakin' The Tree M Virgin Van der Graff Generator A Grounding In Numbers M Virgin Tina Turner Platinum Collection P/E/M Virgin Hall & Oates Collection: H2O, Private Eyes, Voices M RCA Tim Finn Anthology: North South East West P/E/M EMI Music Dist. Mummy Calls Mummy Calls P/E/M Geffen 311 Playlist: The Very Best of 311 P Legacy Various Artists Ashes to Ashes, Series 2 P/E/M Sony Various Artists Rock For Amnesty P/E/M Mercury 2009 Tina Turner The Platinum Collection P Virgin Hall & Oates The Collection: H20/Private Eyes/Voices M RCA Bee Gees The Ultimate Bee Gees: The 50th Anniversary Collection P Rhino Dominic Miller In A Dream P/E/M Independent Lo-Star Closer To The Sun P/E/M Independent Danielle Harmer Superheroes P/E/M EMI Original Soundtrack Ashes to Ashes, Series 2 P Sony Music Various Artists Grandmaster Project P/E/M Extreme Various Artists Now, Vol. -

1 Lecture Notes Jhumpa Lahiri (Born 1967) • “Once in a Lifetime” (2006

Lecture Notes Jhumpa Lahiri (born 1967) • “Once in a Lifetime” (2006) Material Quoted from the Text Appears in Pink Font Some Biographical Highlights ¶¶¶ Jhumpa Lahiri’s first name is a nickname, given to her by a grade-school teacher who found her given name challenging to pronounce. An acclaimed writer of short stories and novels, Lahiri (pictured on the left of this paragraph) mixes cultures, both in her own life and in the lives of many of her fictional characters. She was born in 1967 in London, England, to immigrant parents from Calcutta (now usually spelled Kolkata), capital of the northwest Indian state of West Bengal. When she was just three, the family moved to the U.S. because her father had secured employment as a librarian at the University of Rhode Island. She earned an undergraduate degree (in English) from Barnard College, the women-only college of Columbia University, New York. Next, she obtained three literature-related master’s degrees from Boston University before completing, at the same institution, a PhD in Renaissance Studies. Her international sensibility is further reflected in her mastery of Italian; she has both written and translated fiction in that language. In 2014, President Obama awarded her the National Humanities Medal; and the following year Princeton University appointed her a professor of creative writing. ¶¶¶ Lahiri’s short story titled “Once in a Lifetime” was first published in The New Yorker magazine in 2006 and later republished as part of Unaccustomed Earth (2008), a book of short stories. Hema, the narrator or speaker, may, from early in life, have been pressured by her parents to over-achieve academically. -

NEW RELEASE GUIDE April 3 April 10 ORDERS DUE MARCH 6 ORDERS DUE MARCH 13

ada–music.com @ada_music NEW RELEASE GUIDE April 3 April 10 ORDERS DUE MARCH 6 ORDERS DUE MARCH 13 2020 ISSUE 8 April 3 ORDERS DUE MARCH 6 CLANNAD In a Lifetime Release Date: 4/3/20 H Contains 2 brand new tracks “A Celtic Dream” and “Who Knows (where the time goes)” produced by Trevor Horn H Compiled in collaboration with the band H New cover Imagery from the Anton Corbijn H Two-year farewell worldwide tour starting in February 2020 H Full support of the band H Includes: “Theme From Harry’s Game” and “Robin (The Hooded Man)” Tracklist: 1CD 2CD Standard and 2CD Mediabook 1. An Mhaighdean Mhara 2. Eleanor Plunkett CD1 CD2 3. Crann Úl 1. Thíos Cois Na Trá Domh 1. Atlantic Realm 4. Mheall Sí Lena Glórthaí Mé 2. An Mhaighdean Mhara 2. Voyager 5. Theme From Harry’s Game 3. Eleanor Plunkett 3. A Dream In The Night 6. Robin (The Hooded Man) 4. Coinleach Ghlas An Fhómhair (The Angel & The Soldier Boy) 7. In A Lifetime – with Bono 5. Dúlamán 4. Hourglass 8. Poison Glen 6. Two Sisters 5. Rí Na Cruinne 9. A Bridge (That Carries Us Over) 7. dTigeas a Damhsa 6. Poison Glen 10. A Mhuirnín Ó 8. The Last Rose Of Summer 7. Na Laethe Bhí 11. I Will Find You (Da Dip) (Version #1) 9. Ar a Ghabháil ‘n a ‘Chuain Damh 8. I Will Find You (Theme From “The Last 12. Brave Enough 10. Crann Úl Of The Mohicans”) 13. A Celtic Dream 11. Mheall Sí Lena Glórthaí Mé 9. -

WLIR Playlist

I believe this complete list of WLIR/WDRE songs originally appeared on this site, but the full playlist is no longer available. https://wlir.fm/ It now only has the list of “Screamers and Shrieks” of the week—these were songs voted on by listeners as the best new song of the week. I’ve included the chronological list of Screamers and Shrieks after the full alphabetical playlist by artist. 10,000 Maniacs Candy Everybody Wants 10,000 Maniacs Can't Ignore The Train 10,000 Maniacs Eat For Two 10,000 Maniacs Headstrong 10,000 Maniacs Hey Jack Kerouac 10,000 Maniacs Like The Weather (Non-Live version) 10,000 Maniacs Like The Weather (Live) 10,000 Maniacs Peace Train 10,000 Maniacs These Are Days 10,000 Maniacs Trouble Me 10,000 Maniacs What's The Matter Here 10,000 Maniacs Because The Night 12 Drummers Drumming We'll Be The First Ones 2 NU This Is Ponderous 3D Nearer 4 Of Us Drag My Bad Name Down 9 Ways To Win Close To You 999 High Energy Plan 999 Homicide A Bigger Splash I Don’t Believe A Word (Innocent Bystanders) A Certain Ratio Life's A Scream A Flock Of Seagulls Heartbeat Like A Drum A Flock Of Seagulls I Ran A Flock Of Seagulls It's Not Me Talking A Flock Of Seagulls Living In Heaven A Flock Of Seagulls Never Again (The Dancer) A Flock Of Seagulls Nightmares A Flock Of Seagulls Space Age Love Song A Flock Of Seagulls Telecommunication A Flock Of Seagulls The More You Live The More You Love A Flock Of Seagulls What Am I Supposed To Do A Flock Of Seagulls Who's That Girl A Flock Of Seagulls Wishing A Popular History Of Signs The Ladderjack -

Ladyslipper Catalog Table of Contents

I ____. Ladyslipper Catalog Table of Contents Free Gifts 2 Country The New Spring Crop: New Titles 3 Alternative Rock 5g Celtic * British Isles 12 Rock * Pop 6i Women's Spirituality * New Age 16 R&B * Rap * Dance 64 Recovery 27 Gospel 64 Native American 28 Blues ' 04 Drumming * Percussion 30 Jazz • '. 65 African-American * African-Canadian 31 Classical 67 Women's Music * Feminist Music 33 Spoken .... 68 Comedy 43 Babyslipper Catalog 70 Jewish 44 Mehn's Music 72 Latin American 45 Videos 75 Reggae * Caribbean 47 Songbooks * Sheet Music 80 European 47 Books 81 Arabic * Middle Eastern 49 Jewelry, Cards, T-Shirts, Grab-Bags, Posters 82 African 49 Ordering Information 84 Asian * Pacific 50 Order Blank 85 Folk * Traditional 51 Artist Index 86 Free Gifts We appreciate your support, and would like to say thank you by offering free bonus items with your order! (This offer is for Retail Customers only.) FMNKK ARMSTRONG AWmeuusic PIAYS SO GHMO Order 5 items: Get one Surprise Recording free! Our choice of title and format; order item #FR1000. Order 10 items: choose any 2 of the following free! Order 15 items: choose any 3 of the following free! Order 20 items: choose any 4 of the following free! Order 25 items: choose any 5 of the following free! Order 30 items: choose any 6 of the following free! Please use stock numbers below. #FR1000: Surprise Recording - From Our Grab Bag (our choice) #FR1100: blackgirls: Happy (cassette - p. 52) Credits #FR1300: Frankie Armstrong: ..Music Plays So Grand (cassette - p. 14) #FR1500: Heather Bishop: A Taste of the Blues (LP - p.