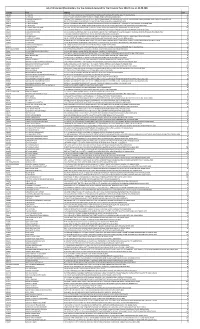

2011 MMUF Journal Highlights the Intellectual Efforts of Current Fellows and Recent Alumni Alike

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bhagat Singh, and Shivaram Rajguru, Whose Conspiracy Led to the Assassination of Deputy Superintendent of Police, J

SWAPNIL SANSAR, ENGLISH WEEKLY,LUCKNOW, 21,MARCH, (07) Sukhdev Thapar, Freeom Fighter Sukhdev Thapar was an revolutionary. He was a senior member of Hindustan in New Delhi (8th April 1929), Sukhdev and his accomplices have been arrest - Socialist Republican Association. He was hanged on 23 March1931 at the age ed and convicted of their crime, going through the loss of life sentence as the of 23.Sukhdev Thapar, born (15 May 1907) in Ludhiana, Punjab, British India to verdict. On twenty-third March 1931, the 3 courageous revolutionaries, Bhagat Ramlal Thapar and Ralli Devi. Sukhdev's father died and he was brought up by Singh, Sukhdev Thapar and Shivaram Rajguru have been hanged, at the same his uncle Lala Achintram.Sukhdev Thapar was a member of the Hindustan time as their bodies were secretly cremated at the banks of the River Sutlej. Socialist Republican Association (HSRA), and organised revolutionary cells in Sukhdev Thapar turned into just 24 years vintage whilst he became a martyr for Punjab and other areas of North India.Sukhdev is best remembered for his his motherland, however, he will usually be remembered for his courage, patri - involvement in the Lahore Conspiracy Case of 18 December 1928 and its after - otism, and sacrifice of his existence for India's independence. Agency. math. He was an accomplice of Bhagat Singh, and Shivaram Rajguru, whose conspiracy led to the assassination of Deputy Superintendent of Police, J. P. Shivaram Hari Rajguru Saunders in 1928 in response to the vio - Shivaram Hari Rajguru was an revolutionary from Maharashtra, known mainly lent death of a veteran leader,On 23 March for his involvement in the assassination of a British Raj police officer.Rajguru 1931, the three men were hanged. -

AP1 Companies Affiliates

AP1 COMPANIES & AFFILIATES 100% RECORDS BIG MUSIC CONNOISSEUR 130701 LTD INTERNATIONAL COLLECTIONS 3 BEAT LABEL BLAIRHILL MEDIA LTD (FIRST NIGHT RECORDS) MANAGEMENT LTD BLIX STREET RECORDS COOKING VINYL LTD A&G PRODUCTIONS LTD (TOON COOL RECORDS) LTD BLUEPRINT RECORDING CR2 RECORDS ABSOLUTE MARKETING CORP CREATION RECORDS INTERNATIONAL LTD BOROUGH MUSIC LTD CREOLE RECORDS ABSOLUTE MARKETING BRAVOUR LTD CUMBANCHA LTD & DISTRIBUTION LTD BREAKBEAT KAOS CURB RECORDS LTD ACE RECORDS LTD BROWNSWOOD D RECORDS LTD (BEAT GOES PUBLIC, BIG RECORDINGS DE ANGELIS RECORDS BEAT, BLUE HORIZON, BUZZIN FLY RECORDS LTD BLUESVILLE, BOPLICITY, CARLTON VIDEO DEAGOSTINI CHISWICK, CONTEMPARY, DEATH IN VEGAS FANTASY, GALAXY, CEEDEE MAIL T/A GLOBESTYLE, JAZZLAND, ANGEL AIR RECS DECLAN COLGAN KENT, MILESTONE, NEW JAZZ, CENTURY MEDIA MUSIC ORIGINAL BLUES, BLUES (PONEGYRIC, DGM) CLASSICS, PABLO, PRESTIGE, CHAMPION RECORDS DEEPER SUBSTANCE (CHEEKY MUSIC, BADBOY, RIVERSIDE, SOUTHBOUND, RECORDS LTD SPECIALTY, STAX) MADHOUSE ) ADA GLOBAL LTD CHANDOS RECORDS DEFECTED RECORDS LTD ADVENTURE RECORDS LTD (2 FOR 1 BEAR ESSENTIALS, (ITH, FLUENTIAL) AIM LTD T/A INDEPENDENTS BRASS, CHACONNE, DELPHIAN RECORDS LTD DAY RECORDINGS COLLECT, FLYBACK, DELTA LEISURE GROPU PLC AIR MUSIC AND MEDIA HISTORIC, SACD) DEMON MUSIC GROUP AIR RECORDINGS LTD CHANNEL FOUR LTD ALBERT PRODUCTIONS TELEVISON (IMP RECORDS) ALL AROUND THE CHAPTER ONE DEUX-ELLES WORLD PRODUCTIONS RECORDS LTD DHARMA RECORDS LTD LTD CHEMIKAL- DISTINCTIVE RECORDS AMG LTD UNDERGROUND LTD (BETTER THE DEVIL) RECORDS DISKY COMMUNICATIONS -

ZQNBA Nuslc I Vbllshing

0 ZQNBA NUslc I vBLlsHING XOMBA ENTERPRISES INC, (ASCAP) 'l37"139 WEST 28TH STREET) NEW YORK, NY 10001 EOMBA SONGS INC (BMI) TELEPHONE: 21 2"727-001 6 FAX: 21 2-229-0822 Testimony Of PAUL KATZ Senior Vice President Of Business Affairs ZOMBA MUSIC PUBLISHING ZOMBA RECORDING CORPORATION New York, New York Before the Copyright Arbitration Royalty Panel Washington, D.C. April 2001 +%DON OFFICEI XOMBA HOUSE) 'I 65 'I 67 HIGH ROAD) WILLESDEN) LONDON NW 10 250) ENGLAND) TELEPHONE: (44) 1814594899) FAX; (44) 181451-3900 EUROPEAN OFFICE: XOMBA MUSIC HOLDINGS 8 V.) HOEFLOO 24) 1251 EB LAREN (N H )) HOLLAND) TELEPHONE (3'I) 3553 'l 6314) FAX (31) 3553 16785 LOS ANGELES OFFICE: 9000 SUNSET BOULEVARD) SUITE 300) LOS ANGELES) CA 90069) TELEPHONE (310) 247"8300) FAX: (310) 247 8366 NASHVILLE OFFICEI 914-916 19TH AVENUE SOUTH, NASHVILLE) TN 37212, TELEPHONEI (615) 321-4850, Fax: (615) 321&616 A ZOMBA COMPANY TABLE OF CONTENTS Pave Background Discussion .. 1. Acquiring the Song.. 3 2. Pitching the Song 4 3. Administering the Song . 5 4. Licensing the Song. 6 5. Collecting and Distributing Royalties . 7 Table 1 U.S. Music Publishing Income — 1998 BACKGROUND I am the Senior Vice President of Business Affairs for Zomba Enterprises Inc. ("Zomba Music Publishing"), which owns and operates a music publishing company, and Zomba Recording Corporation ("Zomba Records"), which owns and operates an independent record company. Both Zomba Music Publishing and Zomba Records are part of the Zomba group of companies, which is privately-owned. Among the singer/songwriters represented by Zomba Music Publishing are Macy Gray, Links Park, R. -

![THE D.A.P. CATALOG MID-SUMMER 2019 Pipilotti Rist, Die Geduld [The Patience], 2016](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9276/the-d-a-p-catalog-mid-summer-2019-pipilotti-rist-die-geduld-the-patience-2016-209276.webp)

THE D.A.P. CATALOG MID-SUMMER 2019 Pipilotti Rist, Die Geduld [The Patience], 2016

THE D.A.P. CATALOG MID-SUMMER 2019 Pipilotti Rist, Die Geduld [The Patience], 2016. Installation view from Kunsthaus Zürich. Photo: Lena Huber. Courtesy the artist, Hauser & Wirth and Luhring Augustine. From Pipilotti Rist: Open My Glade, published by Louisiana Museum of Modern Art. See page 20. Mid-Summer 2019 New Releases 2 CATALOG EDITOR Back in Stock 9 Thomas Evans DESIGNER Lower-Priced Books 10 Martha Ormiston PHOTOGRAPHY Books for Summer 12 Justin Lubliner, Carter Seddon COPY WRITING More New Books 14 Janine DeFeo, Thomas Evans, Megan Ashley DiNoia, Arthur Cañedo, Jack Patterson Recently Published by Steidl 26 FRONT COVER IMAGE Stefan Draschan. from Coincidences at Museums, published by Hatje Cantz. See page 5. SPRING/SUMMER ■ 2019 ■ Basquiat's "Defacement": The Untold Story Text by Chaédria LaBouvier, Nancy Spector, J. Faith Almiron. Police brutality, racism, graffiti and Jean-Michel Basquiat painted Defacement (The Death of Michael Stewart) on the wall of Keith the art world of the early-1980s Haring’s studio in 1983 to commemorate the death of a young black artist, who died from injuries sustained while in police custody after being arrested for allegedly tagging a New York City subway Lower East Side converge in one station. Defacement is the starting point for the present volume, which focuses on Basquiat’s response to anti-black racism and police brutality. Basquiat’s “Defacement” explores this chapter painting by Jean-Michel Basquiat in the artist’s career through both the lens of his identity and the Lower East Side as a nexus of activism in the early 1980s, an era marked by the rise of the art market, the AIDS crisis and ongoing racial tensions in the city. -

OAG Hearing on Interactions Between NYPD and the General Public Submitted Written Testimony

OAG Hearing on Interactions Between NYPD and the General Public Submitted Written Testimony Tahanie Aboushi | New York, New York I am counsel for Dounya Zayer, the protestor who was violently shoved by officer D’Andraia and observed by Commander Edelman. I would like to appear with Dounya to testify at this hearing and I will submit written testimony at a later time but well before the June 15th deadline. Thank you. Marissa Abrahams | South Beach Psychiatric Center | Brooklyn, New York As a nurse, it has been disturbing to see first-hand how few NYPD officers (present en masse at ALL peaceful protests) are wearing the face masks that we know are preventing the spread of COVID-19. Demonstrators are taking this extremely seriously and I saw NYPD literally laugh in the face of a protester who asked why they do not. It is negligent and a blatant provocation -especially in the context of the over-policing of Black and Latinx communities for social distancing violations. The complete disregard of the NYPD for the safety of the people they purportedly protect and serve, the active attacks with tear gas and pepper spray in the midst of a respiratory pandemic, is appalling and unacceptable. Aaron Abrams | Brooklyn, New York I will try to keep these testimonies as precise as possible since I know your office likely has hundreds, if not thousands to go through. Three separate occasions highlighted below: First Incident - May 30th - Brooklyn - peaceful protestors were walking from Prospect Park through the streets early in the day. At one point, police stopped to block the street and asked that we back up. -

Nationalism in India Lesson

DC-1 SEM-2 Paper: Nationalism in India Lesson: Beginning of constitutionalism in India Lesson Developer: Anushka Singh Research scholar, Political Science, University of Delhi 1 Institute of Lifelog learning, University of Delhi Content: Introducing the chapter What is the idea of constitutionalism A brief history of the idea in the West and its introduction in the colony The early nationalists and Indian Councils Act of 1861 and 1892 More promises and fewer deliveries: Government of India Acts, 1909 and 1919 Post 1919 developments and India’s first attempt at constitution writing Government of India Act 1935 and the building blocks to a future constitution The road leading to the transfer of power The theory of constitutionalism at work Conclusion 2 Institute of Lifelog learning, University of Delhi Introduction: The idea of constitutionalism is part of the basic idea of liberalism based on the notion of individual’s right to liberty. Along with other liberal notions,constitutionalism also travelled to India through British colonialism. However, on the one hand, the ideology of liberalism guaranteed the liberal rightsbut one the other hand it denied the same basic right to the colony. The justification to why an advanced liberal nation like England must colonize the ‘not yet’ liberal nation like India was also found within the ideology of liberalism itself. The rationale was that British colonialism in India was like a ‘civilization mission’ to train the colony how to tread the path of liberty.1 However, soon the English educated Indian intellectual class realised the gap between the claim that British Rule made and the oppressive and exploitative reality of colonialism.Consequently,there started the movement towards autonomy and self-governance by Indians. -

Gospel Heritage ’05 Conference Drawing a Who’S Who to Atlanta

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Contact: Sabrina D. Guice Guice Media Communications (678) 565-7539 (EDT) [email protected] Gospel Heritage ’05 Conference Drawing A Who’s Who To Atlanta Kirk Franklin, Andrae Crouch, Donnie McClurkinHezekiah Walker, Vanessa Bell Armstrong, Fred Hammond to headline Black History Month’s largest national Gospel celebration. January 10, 2005, Atlanta, Ga. – The founder and publisher of Gospel Today magazine, Teresa Hairston, will host the Gospel Heritage Foundation’s annual Praise & Worship Conference in the city of Atlanta February 10-12, 2005. Some of the world’s most renowned musicians, singers and praise and worship leaders will all converge on the city for three power packed days. Participating in the conference will be Grammy, Stellar and Dove award winning artists. In attendance will be Kirk Franklin, Andrae Crouch, Donnie McClurkin, Daryl Coley, Hezekiah Walker, Vanessa Bell Armstrong, Fred Hammond and a host of other gospel music pioneers. Conference seminars, workshops, banquets and events will be held at two locations in Atlanta – Word of Faith Worship Center in Austell and the Airport Renaissance Hotel. Historically, this will be the fourth year the conference will be held. Making it even more special this year is the McDonald’s® Corporation hosting of the Youth Division. Highlights will include the Youth/Choir competition to be held at the Renaissance Hotel on Saturday, February 12th at 2:30 p.m. Prizes for the competition will be cash scholarships totaling $10,000. As an incentive to the community, Ms. Hairston has opened all of the conferences evening sessions to the public free of charge. -

This Book Is a Compendium of New Wave Posters. It Is Organized Around the Designers (At Last!)

“This book is a compendium of new wave posters. It is organized around the designers (at last!). It emphasizes the key contribution of Eastern Europe as well as Western Europe, and beyond. And it is a very timely volume, assembled with R|A|P’s usual flair, style and understanding.” –CHRISTOPHER FRAYLING, FROM THE INTRODUCTION 2 artbook.com French New Wave A Revolution in Design Edited by Tony Nourmand. Introduction by Christopher Frayling. The French New Wave of the 1950s and 1960s is one of the most important movements in the history of film. Its fresh energy and vision changed the cinematic landscape, and its style has had a seminal impact on pop culture. The poster artists tasked with selling these Nouvelle Vague films to the masses—in France and internationally—helped to create this style, and in so doing found themselves at the forefront of a revolution in art, graphic design and photography. French New Wave: A Revolution in Design celebrates explosive and groundbreaking poster art that accompanied French New Wave films like The 400 Blows (1959), Jules and Jim (1962) and The Umbrellas of Cherbourg (1964). Featuring posters from over 20 countries, the imagery is accompanied by biographies on more than 100 artists, photographers and designers involved—the first time many of those responsible for promoting and portraying this movement have been properly recognized. This publication spotlights the poster designers who worked alongside directors, cinematographers and actors to define the look of the French New Wave. Artists presented in this volume include Jean-Michel Folon, Boris Grinsson, Waldemar Świerzy, Christian Broutin, Tomasz Rumiński, Hans Hillman, Georges Allard, René Ferracci, Bruno Rehak, Zdeněk Ziegler, Miroslav Vystrcil, Peter Strausfeld, Maciej Hibner, Andrzej Krajewski, Maciej Zbikowski, Josef Vylet’al, Sandro Simeoni, Averardo Ciriello, Marcello Colizzi and many more. -

Full Speed Ahead for DVD Sales by JILL KIPNIS Increase Another 49% in 2003

$6.95 (U.S.), $8.95 (CAN.), £5.50 (U.K.), 8.95 (EUROPE), Y2,500 (JAPAN) II.L.II..I.JJL.1I.1I.II.LJII I ILIi #BXNCCVR ******* ************** 3 -DIGIT 908 #908070EE374EM002# * BLBD 880 A06 B0105 001 MAR 04 2 MONTY GREENLY 3740 ELM AVE # A LONG BEACH CA 90807 -3402 THE INTERNATIONAL NEWSWEEKLY OF MUSIC, VIDEO, AND HOME ENTERTAINMENT APRIL 5, 2003 Patriotism Lifts Pro -War Songs; Chicks Suffer A Billboard and Airplay Moni- Last week, the Chicks' "Travelin' tor staff report Soldier," a record that many thought With the war in Iraq now more would become an anthem for the than a week old and displays of sup- troops in the event of war, instead port for the war increasing, went 1 -3 on the Billboard Linkin Park Enjoys Meteoric Opening radio responded on several Some Acts Nix Hot Country Singles & fronts. The biggest victims International Tracks chart in the wake BY LARRY FLICK Show by Eminem, which sold 1.3 million copies in of the patriotic surge have Tours In Light of singer Natalie Maims' NEW YORK -Based on first -day sales activity for its its first full week of sales for the week ending June been Dixie Chicks, whose Of War: anti -war/anti -President new album, Meteora, Linkin Park could enjoy the 2, 2002, according to Nielsen SoundScan. Seven - tracks suffered major air- See Page 7 Bush comments (Bill- first 1 million -selling week of 2003. Early estimates day sales of more than 900,000 units would score play losses at their host for- board, March 29). -

For the Dividend Declared for the Financial Year 2012-13 As on 12.09.2017

List of Unclaimed Shareholders: For the dividend declared for the Financial Year 2012-13 as on 12.09.2017 FOLIO NO NAME ADDRESS AMT A04314 A B FONTES 104 IVTH CROSS KALASIPALYAM NEW EXTENSION BANGALORE BANGALORE,KARNATAKA,PIN-560002,INDIA 25 A17671 A C SRAJAN 66 LUZ CHURCH ROAD MYLAPORE CHENNAI CHENNAI,TAMIL NADU,PIN-600004,INDIA 180 D00252 A DHAKSHINAMOORTHY PARTNER V M C TRADERS STOCKISTS OF A C LTD 6/10 MARIAMMAN KOIL RAMANATHAPURAM DT RAMANATHAPURAM RAMNAD,TAMIL NADU,PIN-623501,INDIA 90 A02076 A JANARDHAN 8/1101 SESHAGIRINIVAS NEW ROAD COCHIN COCHIN ERNAKULAM,KERALA,PIN-682002,INDIA 25 A02270 A K BHATTACHARYA UNITED COMMERCIAL BANK MATA ANANDA NAGAR SHIVALA HOSPITAL VARANASI U P VARANASI,UTTAR PRADESH,PIN-221001,INDIA 25 A03705 A K NARAYANA C/O A K KESAUACHAR 451 TENTH CROSS GIRINAGAR SECOND PHASE BANGALORE BANGALORE,KARNATAKA,PIN-560085,INDIA 25 P00351 A K RAMACHANDRAPRABHU 'PAVITRA' NO 949 24TH MAIN ROAD J P NAGAR II PHASE BANGALORE BANGALORE,KARNATAKA,PIN-560078,INDIA 360 A17411 A KALPAKAM NARAYAN C/O V KAMESWARARAO 7-6-108 ENUGULAMALAL STREET SRIKAKULAM (A.P.) SRIKAKULAM,ANDHRA PRADESH,PIN-532001,INDIA 18 A03555 A LAKSHMINARAYANA C/O G ARUNACHALAM RANA PLOT NO 30 LEPAKSHI COLONY WEST MARREDPALLY SECUNDERABAD HYDERABAD,ANDHRA PRADESH,PIN-500026,INDIA 25 A04366 A M DAVID 1 MISSION COMPOUND AJMER ROAD JAIPUR JAIPUR,RAJASTHAN,PIN-302006,INDIA 25 M00394 A MURUGESAN 3 A D BLOCK V G RAO NAGAR EXTENSION KATPADI P O VELLORE N A A DT VELLORE NORTH ARCOT,TAMIL NADU,PIN-632007,INDIA 23 A17672 A N VENKATALAKSHMI 361 XI A CROSS 29TH MAIN J -

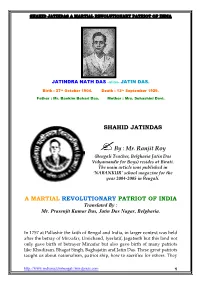

JATINDRA NATH DAS -Alias- JATIN DAS

JATINDRA NATH DAS -alias- JATIN DAS. Birth : 27 th October 1904. Death : 13 th September 1929. Father : Mr. Bankim Behari Das. Mother : Mrs. Suhashini Devi. SHAHID JATINDAS ?By : Mr. Ranjit Roy (Bengali Teacher, Belgharia Jatin Das Vidyamandir for Boys) resides at Birati. The main article was published in ‘NABANKUR’ school magazine for the year 2004-2005 in Bengali. A MARTIAL REVOLUTIONARY PATRIOT OF INDIA Translated By : Mr. Prasenjit Kumar Das, Jatin Das Nagar, Belgharia. In 1757 at Pallashir the faith of Bengal and India, in larger context was held after the betray of Mirzafar, Umichand, Iyerlatif, Jagatseth but this land not only gave birth of betrayer Mirzafar but also gave birth of many patriots like Khudiram, Bhagat Singh, Baghajatin and Jatin Das. These great patriots taught us about nationalism, patriot ship, how to sacrifice for others. They http://www.indianactsinbengali.wordpress.com 1 have tried their best to uphold the head of a unified, independent and united nation. Let us discuss about one of them, Jatin Das and his great sacrifice towards the nation. on 27 th October 1904 Jatin Das (alias Jatindra Nath Das) came to free the nation from the bondage of the British Rulers. He born at his Mother’s house at Sikdar Bagan. He was the first child of father Bankim Behari Das and mother Suhashini Devi. After birth the newborn did not cried for some time then the child cried loudly, it seems that the little one was busy in enchanting the speeches of motherland but when he saw that his motherland is crying for her bondage the little one cant stop crying. -

The Failure of Local and Federal Prosecutors to Curb Police Brutality, 30 Fordham Urb

Fordham Urban Law Journal Volume 30 | Number 2 Article 7 2003 The aiF lure of Local and Federal Prosecutors to Curb Police Brutality Asit S. Panwala Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/ulj Part of the Criminal Law Commons Recommended Citation Asit S. Panwala, The Failure of Local and Federal Prosecutors to Curb Police Brutality, 30 Fordham Urb. L.J. 639 (2002). Available at: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/ulj/vol30/iss2/7 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by FLASH: The orF dham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. It has been accepted for inclusion in Fordham Urban Law Journal by an authorized editor of FLASH: The orF dham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The aiF lure of Local and Federal Prosecutors to Curb Police Brutality Cover Page Footnote The Author ouldw like to thank Christine Chen, Anthony Thompson, and Ronald Goldstock for their support and help in this endeavor. This article is available in Fordham Urban Law Journal: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/ulj/vol30/iss2/7 THE FAILURE OF LOCAL AND FEDERAL PROSECUTORS TO CURB POLICE BRUTALITY Asit S. Panwala* INTRODUCTION Excessive use of force by police officers undermines faith in the criminal justice system. Citizens expect those with badges and guns to follow the law as well as enforce it, but these two roles often come into conflict. Reporter Craig Horowitz recounted that one police officer justified his hitting a suspect in the stomach when the suspect tried to run away as being necessary to reestablish author- ity.1 Another police officer is quoted as saying, "[i]f someone disses you, you take him in an alley and slap him.