War and Denial

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Contribution of Bengal in Freedom Struggle by CDT Nikita Maity Reg No

Contribution of Bengal in freedom struggle By CDT Nikita Maity Reg No: WB19SWN136584 No 1 Bengal Naval NCC Unit Kol-C, WB&Sikkim Directorate Freedom is something which given to every organism who has born on this Earth. It is that right which is given to everyone irrespective of anything. India (Bharat) was one of prosperous country of the world and people from different parts of world had come to rule over her, want to take her culture and heritage but she had always been brave and protected herself from various invaders. The last and the worst invader was British East India Company. BEIC not only drained India‟s wealth but also had destroyed our rich culture and knowledge. They had tried to completely destroy India in every aspect. But we Indian were not going to let them be successful in their dirty plan. Every section of Indian society had revolved in their own way. One of the major and consistent revolved was going in then Bengal province. In Bengal, from writer to fighter and from men to women everyone had given everything for freedom. One of the prominent forefront freedom fighter was Netaji Shubhas Chandra Bose. Netaji was born on 23rd January, 1897 in Cuttack. He had studied in Presidency College. In 1920 he passed the civil service examination, but in April 1921, after hearing of the nationalist turmoil in India, he resigned his candidacy and hurried back to India. He started the newspaper 'Swaraj'. He was founder of Indian National Army(INA) or Azad Hind Fauj. There was also an all-women regiment named after Rani of Jhanshi, Lakshmibai. -

Directorate of Civil Defence Police Department

Directorate of Civil Defence Police Department NOTE ON HOME GUARDS & CIVIL DEFENCE Formation of the Home Guards in the state: In the wake of Chinese aggression in October 1962 and as per Tamil Nadu Home Guards Rules 1963 the HGs organization has come into being in Tamilnadu. 2. Strength: As on date there are 105 ½ companies of HGs (80.5 men companies and 25 women companies viz.,) totalling 11,622 Home guards including 2750 women Home guards. All the districts and all the Police Commissionerates are having Home guards units including women HG wing. 3. Organisational set up: The Home Guards organization is basically voluntary in character and all the Home guard personnel being civilians are volunteers. i) Central level: At the central level the Director General, National Emergency Response Force & Civil Defence is responsible for all policy matters concerning rising, training and equipping of Home guards in the country. He is assisted by a Dy.Director General, HGs, an Asst.Dir.Genl. Home guards, a senior staff officer, Home Guards and a junior staff officer together with the secretariat staff. ii) State level: The following is the state level set up of Home guards organisation: a) Director Genl.of Police : Commandant Genl. of Home Guards b) I.G.P : Dy.CMT Genl. Home guards c) District SPs / COPs : Commandants, Home Guards of their respective district / city unit. d) Asst.CMTs General : Civilians (There are six A.C.Gs in Tamilnadu - ACGs South zone @ Tiruppur, Villupuram range & Cuddlore, Vellore range & Vellore, Chennai city @ Chennai, Tirunelveli range @ Tirunelveli and Ooty and Trichy range at Trichy. -

Oxford Book Fair List 2014

BERNARD QUARITCH LTD OXFORD BOOK FAIR LIST including NEW ACQUISITIONS ● APRIL 2014 Main Hall, Oxford Brookes University (Headington Hill Campus) Gipsy Lane, Oxford OX3 0BP Stand 87 Saturday 26th April 12 noon – 6pm - & - Sunday 27th April 10am – 4pm A MEMOIR OF JOHN ADAM, PRESENTED TO THE FORMER PRIME MINISTER LORD GRENVILLE BY WILLIAM ADAM 1. [ADAM, William (editor).] Description and Representation of the Mural Monument, Erected in the Cathedral of Calcutta, by General Subscription, to the Memory of John Adam, Designed and Executed by Richard Westmacott, R.A. [?Edinburgh, ?William Adam, circa 1830]. 4to (262 x 203mm), pp. [4 (blank ll.)], [1]-2 (‘Address of the British Inhabitants of Calcutta, to John Adam, on his Embarking for England in March 1825’), [2 (contents, verso blank)], [2 (blank l.)], [2 (title, verso blank)], [1]-2 (‘Description of the Monument’), [2 (‘Inscription on the Base of the Tomb’, verso blank)], [2 (‘Translation of Claudian’)], [1 (‘Extract of a Letter from … Reginald Heber … to … Charles Williams Wynn’)], [2 (‘Extract from a Sermon of Bishop Heber, Preached at Calcutta on Christmas Day, 1825’)], [1 (blank)]; mounted engraved plate on india by J. Horsburgh after Westmacott, retaining tissue guard; some light spotting, a little heavier on plate; contemporary straight-grained [?Scottish] black morocco [?for Adam for presentation], endpapers watermarked 1829, boards with broad borders of palmette and flower-and-thistle rolls, upper board lettered in blind ‘Monument to John Adam Erected at Calcutta 1827’, turn-ins roll-tooled in blind, mustard-yellow endpapers, all edges gilt; slightly rubbed and scuffed, otherwise very good; provenance: William Wyndham Grenville, Baron Grenville, 3 March 1830 (1759-1834, autograph presentation inscription from William Adam on preliminary blank and tipped-in autograph letter signed from Adam to Grenville, Edinburgh, 6 March 1830, 3pp on a bifolium, addressed on final page). -

S. of Shri Mali Chikkapapanna; B. June 5, 1937; M. Shrimati Kenchamma, 1 D.; Member, Rajya Sabha, 3-4-1980 to 2-4-1986

M MADDANNA, SHRI M. : Studied upto B.A.; Congress (I) (Karnataka); s. of Shri Mali Chikkapapanna; b. June 5, 1937; m. Shrimati Kenchamma, 1 d.; Member, Rajya Sabha, 3-4-1980 to 2-4-1986. Per. Add. : 5, III Cross, Annayappa Block, Kumara Park West, Bangalore (Karnataka). MADHAVAN, SHRI K. K. : B.A., LL.B.; Congress (U) (Kerala); s. of Shri Kunhan; b. July 23, 1917; m. Shrimati Devi, 1 s. and 1 d.; Member, (i) Kerala Legislative Assembly, 1965 and (ii) Rajya Sabha, 3-4-1976 to 2-4-1982; Died. Obit. on 21-10-1999. MADHAVAN, SHRI S. : B.Com., B.L.; A.I.A.D.M.K. (Tamil Nadu); s .of Shri Selliah Pillai; b . October 3, 1933; m. Shrimati Dhanalakshmi, 1 s. and 2 d.; Member, Tamil Nadu Legislative Assembly, 1962-76 and 1984-87; Minister, Government of Tamil Nadu, 1967-76; Member, Rajya Sabha, 3-4-1990 to 2-4- 1996. Per. Add. : 17, Sixth Main Road, Raja Annamalai Puram, Madras (Tamil Nadu). MADNI, SHRI MAULANA ASAD : Fazil (equivalent to M.A. in Islamic Theology); Congress (I) (Uttar Pradesh); s. of Maulana Hussain Ahmad Madni; b. 1928; m. Shrimati Barirah Bano, 4 s. and 2 d.; Vice-President, U.P.C.C.; Member, Rajya Sabha, 3-4-1968 to 2-4-1974, 5-7-1980 to 4-7-1986 and 3-4-1988 to 2-4-1994. Per. Add . : Madani Manzil , Deoband , District Saharanpur (Uttar Pradesh). MAHABIR PRASAD, DR. : M.A., Ph.D.; Janata Party (Bihar); s. of Shri Sahdev Yadav; b. 1939; m. Shrimati Chandra Kala Devi, 2 s. -

Sri Aurobindo and the Cripps Mission to India

Sri Aurobindo and the Cripps Mission to India (March- April 1942) Table of Contents Draft Declaration for Discussion with Indian Leaders 3 Messages of Sri Aurobindo about Sir Stafford Cripps’s Mission 6 Twelve Years with Sri Aurobindo by Nirodbaran (Extracts) 7 The Transfer of Power in India by V.P. Menon, The Cripps Mission 21 Struggle for Freedom by R.C. Majumdar (Extracts) 54 Annexure Mother’s Agenda, Vol 3, November 17, 1962 66 Mother’s Agenda, Vol 4, June 15, 1963 69 Prime Minister Winston Churchill's Announcement 71 Statement and Draft Declaration by His Majesty's Government 74 Sir Stafford Cripps Review of Negotiations 77 Sir Stafford Cripps Statement on India 81 Prime Minister Winston Churchill's Report to the House 86 On Wavell’s and the Cabinet Mission 92 2 Draft of Cripps Declaration for Discussion with Indian Leaders (as published) 30 March 1942 The conclusions of the British War Cabinet as set out below are those which Sir Stafford Cripps has taken with him for discussion with the Indian Leaders and the question as to whether they will be implemented will depend upon the outcome of these discussions which are now taking place. His Majesty's Government, having considered the anxieties expressed in this country and in India as to the fulfillment of the promises made in regard to the future of India, have decided to lay down in precise and clear terms the steps which they propose shall be taken for the earliest possible realisation of self-government in India. The object is the creation of a new Indian Union which shall constitute a Dominion, associated with the United Kingdom and the other Dominions by a common allegiance to the Crown, but equal to them in every respect, in no way subordinate in any aspect of its domestic or external affairs. -

Biographies Introduction V4 0

2020 www.BritishMilitaryHistory.co.uk Author: Robert PALMER, M.A. BRITISH MILITARY HISTORY BIOGRAPHIES An introduction to the Biographies of officers in the British Army and pre-partition Indian Army published on the web-site www.BritishMilitaryHistory.co.uk, including: • Explanation of Terms, • Regular Army, Militia and Territorial Army, • Type and Status of Officers, • Rank Structure, • The Establishment, • Staff and Command Courses, • Appointments, • Awards and Honours. Copyright ©www.BritishMilitaryHistory.co.uk (2020) 13 May 2020 [BRITISH MILITARY HISTORY BIOGRAPHIES] British Military History Biographies This web-site contains selected biographies of some senior officers of the British Army and Indian Army who achieved some distinction, notable achievement, or senior appointment during the Second World War. These biographies have been compiled from a variety of sources, which have then been subject to scrutiny and cross-checking. The main sources are:1 ➢ Who was Who, ➢ Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, ➢ British Library File L/MIL/14 Indian Army Officer’s Records, ➢ Various Army Lists from January 1930 to April 1946: http://www.archive.org/search.php?query=army%20list ➢ Half Year Army List published January 1942: http://www.archive.org/details/armylisthalfjan1942grea ➢ War Services of British Army Officers 1939-46 (Half Yearly Army List 1946), ➢ The London Gazette: http://www.london-gazette.co.uk/, ➢ Generals.dk http://www.generals.dk/, ➢ WWII Unit Histories http://www.unithistories.com/, ➢ Companions of The Distinguished Service Order 1923 – 2010 Army Awards by Doug V. P. HEARNS, C.D. ➢ Various published biographies, divisional histories, regimental and unit histories owned by the author. It has to be borne in mind that discrepancies between sources are inevitable. -

Hungry Bengal: War, Famine, Riots, and the End of Empire 1939-1946

Hungry Bengal: War, Famine, Riots, and the End of Empire 1939-1946 By Janam Mukherjee A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Anthropology and History) In the University of Michigan 2011 Doctoral Committee: Professor Barbara D. Metcalf, Chair Emeritus Professor David W. Cohen Associate Professor Stuart Kirsch Associate Professor Christi Merrill 1 "Unknown to me the wounds of the famine of 1943, the barbarities of war, the horror of the communal riots of 1946 were impinging on my style and engraving themselves on it, till there came a time when whatever I did, whether it was chiseling a piece of wood, or burning metal with acid to create a gaping hole, or cutting and tearing with no premeditated design, it would throw up innumerable wounds, bodying forth a single theme - the figures of the deprived, the destitute and the abandoned converging on us from all directions. The first chalk marks of famine that had passed from the fingers to engrave themselves on the heart persist indelibly." 2 Somnath Hore 1 Somnath Hore. "The Holocaust." Sculpture. Indian Writing, October 3, 2006. Web (http://indianwriting.blogsome.com/2006/10/03/somnath-hore/) accessed 04/19/2011. 2 Quoted in N. Sarkar, p. 32 © Janam S. Mukherjee 2011 To my father ii Acknowledgements I would like to thank first and foremost my father, Dr. Kalinath Mukherjee, without whom this work would not have been written. This project began, in fact, as a collaborative effort, which is how it also comes to conclusion. His always gentle, thoughtful and brilliant spirit has been guiding this work since his death in May of 2002 - and this is still our work. -

India and World War II: War, Armed Forces, and Society, 1939-45 by Kaushik Roy, New Delhi: Oxford University Press, 2016, Pp

India and World War II: War, Armed Forces, and Society, 1939-45 by Kaushik Roy, New Delhi: Oxford University Press, 2016, pp. xxi + 402, INR 1,645 Manas Dutta* World War II (1939-45) was a watershed moment in modern world history. It drastically changed the social and political map of the world, and especially of the Indian subcontinent which was under colonial rule at that time. Several significant works have appeared in recent times on the diverse aspects of the war. Among them is Kaushik Roy’s authoritative account, India and World War II: War, Armed Forces, and Society, 1939-45. It has been well argued that the dominant historical narratives of World War II have been predominantly Eurocentric. India has received relatively less critical attention in terms of its contribution to and participation in the war. Roy’s book asserts strongly that India underwent extraordinary and irreversible changes between 1939 and 1945. The entire environment of the subcontinent underwent change as thousands of natives put on the military uniform to fight in places like West Asia, Malaya, Burma, Iraq, Iran, Syria, North and East Africa, Sicily, mainland Italy, Greece, Crete, Cyprus, Ethiopia, Eritrea, and Somaliland. India was the dividing line between two theatres of war—in the West, against Germany, and in the East, against Japan. Roy begins by stating that World War II remains a defining chapter in modern world history (p.1). Colonial India’s involvement in the war * The reviewer is Assistant Professor, Department of History, Kazi Nazrul University,West Bengal, India. ISSN 0976-1004 print © 2017 Institute for Defence Studies and Analyses Journal of Defence Studies, Vol. -

The Great Calcutta Killings Noakhali Genocide

1946 : THE GREAT CALCUTTA KILLINGS AND NOAKHALI GENOCIDE 1946 : THE GREAT CALCUTTA KILLINGS AND NOAKHALI GENOCIDE A HISTORICAL STUDY DINESH CHANDRA SINHA : ASHOK DASGUPTA No part of this publication can be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior permission of the author and the publisher. Published by Sri Himansu Maity 3B, Dinabandhu Lane Kolkata-700006 Edition First, 2011 Price ` 500.00 (Rupees Five Hundred Only) US $25 (US Dollars Twenty Five Only) © Reserved Printed at Mahamaya Press & Binding, Kolkata Available at Tuhina Prakashani 12/C, Bankim Chatterjee Street Kolkata-700073 Dedication In memory of those insatiate souls who had fallen victims to the swords and bullets of the protagonist of partition and Pakistan; and also those who had to undergo unparalleled brutality and humility and then forcibly uprooted from ancestral hearth and home. PREFACE What prompted us in writing this Book. As the saying goes, truth is the first casualty of war; so is true history, the first casualty of India’s struggle for independence. We, the Hindus of Bengal happen to be one of the worst victims of Islamic intolerance in the world. Bengal, which had been under Islamic attack for centuries, beginning with the invasion of the Turkish marauder Bakhtiyar Khilji eight hundred years back. We had a respite from Islamic rule for about two hundred years after the English East India Company defeated the Muslim ruler of Bengal. Siraj-ud-daulah in 1757. But gradually, Bengal had been turned into a Muslim majority province. -

THE EARLS of DALHOUSIE WHO WERE ALSO MEMBERS of the MOST ANCIENT and MOST NOBLE ORDER of the THISTLE (From Dennis Hurt and Wayne R

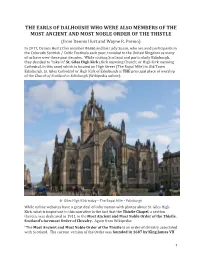

THE EARLS OF DALHOUSIE WHO WERE ALSO MEMBERS OF THE MOST ANCIENT AND MOST NOBLE ORDER OF THE THISTLE (from Dennis Hurt and Wayne R. Premo) In 2017, Dennis Hurt (Clan member #636) and his Lady Susan, who are avid participants in the Colorado Scottish / Celtic Festivals each year, traveled to the United Kingdom as many of us have over these past decades. While visiting Scotland and particularly Edinburgh, they decided to “take in” St. Giles High Kirk (Kirk meaning Church; or High Kirk meaning Cathedral, in this case) which is located on High Street (The Royal Mile) in Old Town Edinburgh. St. Giles Cathedral or High Kirk of Edinburgh is THE principal place of worship of the Church of Scotland in Edinburgh (Wikipedia online). St. Giles High Kirk today – The Royal Mile – Edinburgh While online websites have a great deal of information with photos about St. Giles High Kirk, what is important to this narrative is the fact that the Thistle Chapel, a section therein, was dedicated in 1911 to the Most AnCient anD Most Noble OrDer oF the Thistle, SCotlanD’s Foremost OrDer oF Chivalry. Again from Wikipedia: “The Most AnCient anD Most Noble OrDer oF the Thistle is an order of chivalry associated with Scotland. The current version of the Order was founded in 1687 by King James VII 1 of ScotlanD (James II of England and Ireland) who asserted that he was reviving an earlier Order. The Order consists of the Sovereign and sixteen Knights and Ladies, as well as certain "extra" knights (members of the British Royal Family and foreign monarchs). -

Downloaded 2021-09-27T03:18:32Z

Provided by the author(s) and University College Dublin Library in accordance with publisher policies. Please cite the published version when available. Title The ripple that drowns? Twentieth-century famines in China and India as economic history Authors(s) Ó Gráda, Cormac Publication date 2007-11 Series UCD Centre for Economic Research Working Paper Series; WP07/19 Publisher University College Dublin; Centre for Economic Research Link to online version http://www.ucd.ie/economics/research/papers/2007/WP07.19.pdf Item record/more information http://hdl.handle.net/10197/473 Downloaded 2021-09-27T03:18:32Z The UCD community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters! (@ucd_oa) © Some rights reserved. For more information, please see the item record link above. UCD CENTRE FOR ECONOMIC RESEARCH WORKING PAPER SERIES 2007 The Ripple that Drowns? Twentieth-century famines in China and India as economic history Cormac Ó Gráda, University College Dublin WP07/19 November 2007 UCD SCHOOL OF ECONOMICS UNIVERSITY COLLEGE DUBLIN BELFIELD DUBLIN 4 THE RIPPLE THAT DROWNS? TWENTIETH-CENTURY FAMINES IN CHINA AND INDIA AS ECONOMIC HISTORY Cormac Ó Gráda University College, Dublin I. Introduction Major famines are rare today, and tend to be ‘man-made’. Where crop failure is the main threat, as in southern Africa in 2002 and Niger in 2005, a combination of public action, market forces, and food aid tends to mitigate excess mortality. Although non- crisis death rates in sub-Saharan Africa remain high, excess mortality from famine in 2002 and 2005 was miniscule. The twentieth century saw the virtual elimination of famines caused simply by crop failures. -

Women's Struggle in Quit India Movement

International Journal of Engineering Technology Science and Research IJETSR www.ijetsr.com ISSN 2394 – 3386 Volume 2, Issue 11 November 2015 Women's struggle in Quit India Movement Mrs. Pooja Garima Assistant Professor Assistant Professor Deptt. of History Deptt. of English M.P.College for women, Dabwali M.P. College for women, Dabwali WOMEN'S STRUGGLE IN QUIT INDIA MOVEMENT We are the Independent citizens of Independent India. We got this freedom because of thousands of known and unknown Indians who sacrificed their lives smilingly to get this freedom. In this struggle not only men came forward, but women also forsook the shelter of their homes and with unfailing courage and endurance stood shoulder to shoulder with their menfolk in the frontline of India’s freedom fighters to share with them the sacrifices and triumphs of the struggle. We have heard the name of Rani Laxmi Bai who faced Britishers with exceptional bravery during 1857 freedom revolt but few know about the courageous stories of females contribution during ‘Quit India Movement’. When the Second World War broke out, India was committed to belligerency by the British without any consideration for the feelings of Indians or any assurance of Indian Self-Government. In, protest the congress ministers in the provinces resigned and Gandhiji commenced Individual Satyagraha to express the country's disgust. When the pressure of war mounted, particularly with the advances of Japan in South East Asia, Britain became anxious to secure the full and active co-operation of India in the war efforts. The Cripps Missions came with a promise of dominion status and a plan for future constitutional developments.