RCED-83-86 the Household Goods Moving Industry

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

IN the UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT for the SOUTHERN DISTRICT of TEXAS HOUSTON DIVISION TRAN ENTERPRISES, LLC D/B/A § NUTRITION

Case 4:08-cv-02748 Document 28 Filed in TXSD on 12/03/09 Page 1 of 28 IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF TEXAS HOUSTON DIVISION TRAN ENTERPRISES, LLC d/b/a § NUTRITION DEPOT, § § Plaintiff, § § CIVIL ACTION NO. H-08-2748 v. § § DHL EXPRESS (USA), INC., § § Defendant. § MEMORANDUM AND ORDER Tran Enterprises LLC, doing business as Nutrition Depot, sued DHL Express, a package carrier hired by Nutrition Depot. Nutrition Depot alleged that DHL failed to collect and remit $21,991.72 in collect-on-delivery (COD) payments for shipments DHL delivered to Nutrition Depot customers between April 3, 2006 and January 31, 2007. In the Second Amended Complaint, filed after removal, Nutrition Depot asserted that the Carmack Amendment to the Interstate Commerce Act, 49 U.S.C. § 14706, applied; asserted Texas common-law claims for breach of fiduciary duty, breach of contract, and conversion; and asserted a claim under the Texas Theft Liability Act, TEX. CIV. PRAC. & REM. CODE § 134.001, et seq. In addition to the $21,999.72 in actual damages, Nutrition Depot seeks between $75,375 and $80,775 in attorney’s fees. The following motions are pending: C Nutrition Depot has moved for summary judgment on its state-law claims for breach of fiduciary duty, breach of contract, conversion, and theft of property. (Docket Entry No. 19). DHL has responded, (Docket Entry No. 20), and Nutrition Depot has Case 4:08-cv-02748 Document 28 Filed in TXSD on 12/03/09 Page 2 of 28 replied, seeking summary judgment that DHL is also liable under the Carmack Amendment, (Docket Entry No. -

2012 Fall Convention

C P P C Welcome! Claims Prevention & Procedure Council, INC. 2012 Fall Convention We’re Glad You’ve Joined Us! October 7th, 8th & 9th, 2012 The Menger Hotel San Antonio, Texas C P P C BOARD OF DIRECTORS PRESIDENT Deborah Williams (Insurance) Unirisc (407) 228-2026 [email protected] VICE PRESIDENT Dan Manning (Rep.) Manning Claim Services (201) 612-8670 [email protected] SECRETARY Dori Bledsoe (Mvg/Stg Agent) Covan World-Wide Moving (800) 239-1116 [email protected] TREASURER Don Kistner (Rep.) Kistner’s Full Claims Service, Inc. (309) 786-5868 [email protected] DIRECTORS Bob Dickson (Rep.) Furniture Medic by Bluegrass Restoration (859) 272-4000 [email protected] Linda Hamilton (V.L.) SIRVA: Allied/NAVL (260) 429-3267 [email protected] Terry Jiminez (Rep.) Universal Restoration Services (408) 998-3499 [email protected] Kathy Kendall Wheaton World Wide Moving/Bekins Van Lines (317) 504-0766 [email protected] Kimmie Loeffler (Mvg/Stg Agnt) Armstrong Relocation (888) 827-4156 / (270) 827-4156 [email protected] Brenda McCandless (V.L.) Atlas World Group, Inc. (812) 424-4326, Ext. X-2550 [email protected] Bill See (Rep.) See Restorations Unltd., Inc. (770) 455-4164 [email protected] Mitch Treider (Rep.) Complete Furniture & Interiors (321) 269-1141 [email protected] Mark Weathersby (Rep.) Craftsmanship by Weathersby (757) 464-9150 [email protected] Tim Woody (V.L.) United VL/Mayflower Transit (636) 305-4140 [email protected] EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR Alan R. Jobe (866) 276-5656 [email protected] C P P C President’s Message Hello everyone and welcome to the 2012 Fall Convention here in San Antonio, TX! You should know that this is the first time that the CPPC and AMSA have scheduled their events at the same location, and we are very excited about this joint venture. -

Mediocreat Best

MEDIOCRE AT BEST The CCJ Top 250’s specialized carriers fared best – and worst – in 2007. But most general freight carriers saw anemic growth – or none at all. BY AVERY VISE t the time, most trucking Three carriers that were in A widespread slowdown companies probably saw last year’s CCJ Top 250 – No. The CCJ Top 250’s growth slowed A2007 as fairly miserable – 67 Performance Transportation further in 2007. Revenues grew 3.9 soft freight demand, ample capacity Services, No. 88 Jevic Transportation percent, down from the 9 percent and high fuel prices. Diesel averaged and No. 248 Alvan Motor Freight – increase recorded the year before and $2.89 a gallon in 2007, rising steadily ceased operations this year and so the 16.1 percent rise in 2005 over throughout the year from a low have been dropped from this year’s 2004. For LTL and truckload gen- of $2.41 in January to an unprec- CCJ Top 250. Fuel wasn’t the lone eral freight carriers – the majority of edented $3.44 by late November. culprit. For example, the troubled the CCJ Top 250 – 2007 was truly a For many, those were the good old automobile industry contributed to lackluster year. In fact, 2007 was just days. Today’s diesel prices are more the demise of Alvan Motor Freight another 2006 for LTL carriers, which than 35 percent higher than even the and car hauler PTS, which shut saw no change in revenues. Truckload highest average price during 2007. down in bankruptcy principally due general freight carriers posted a 3.3 Escalating prices coupled with the lag to a Teamsters strike. -

Approved Storage Facilities Address City Province Postal 17Th Street Storage Ltd

APPROVED STORAGE FACILITIES ADDRESS CITY PROVINCE POSTAL 17TH STREET STORAGE LTD. 7403 - 17 STREET EDMONTON AB T6P 1P1 20/20 STORAGE RR #3 VEGREVILLE AB T9G 1T7 2-A MINI STORAGE 730 HIGHFIELD GATE CARSTAIRS AB T0M 0N0 A AWARD MOVING & STORAGE 6149 - 80 ST. EDMONTON AB T6E 2W8 A STORAGE COMPANY 815 MORAINE ROAD NE CALGARY AB T32 2A5 A STORAGE COMPANY BOX 1133 OKOTOKS AB T15 1B2 A STORAGE COMPANY INC 130 COMMERCIAL COURT CALGARY AB T3Z 2A5 A Z MINI STORAGE 6306 47TH AVE WETASKIWIN AB T9A 2G4 A-1 MOVING & STORAGE 12946 - 54 STREET EDMONTON AB T5A 5A8 A1 STORAGE 5505 BROADWAY AVENUE BLACKFALDS AB T0M 0J0 A-1 STORAGE FACILITY 5608 - 62 STREET TABER AB T1G 1Y5 AAA ACADIA MOVING & STORAGE 9976 - 29 AVENUE EDMONTON AB T6N 1A2 AAA APARTMENT MOVERS 16715 - 113 AVENUE EDMONTON AB T5L 4L6 AAA MOVING & STORAGE 1510 - 10 AVENUE SW CALGARY AB T3C 0J5 A-ABCAN MOVING 7516 - 36 ST. NE CALGARY AB T2E 6V2 AAIMS STORAGE 10812 - 99 STREET CLAIRMONT AB T0H 0W0 AB FIRST CHOICE 6321 -76TH AVENUE EDMONTON AB T6B 0A7 AB STORAGE 4904 - 79 STREET RED DEER AB T4P 2V2 AB STORAGE SOUTH 203 PETROLIUM PARK RED DEER AB T4E 8T6 AB STORAGE SOUTH 203-37565 HWY #2 RED DEER COUNTY AB T4E 1B4 ABUHLER'S MOVING & STORAGE BAY 36, 5225 - 5TH STREET NE CALGARY AB T2E 8T6 ACADEMY MOVING 4217 - 16A STREET SE CALGARY AB T2G 3T9 ACCESS MINI STORAGE 603 EASTLAKE ROAK, BOX 3474 AIRDRIE AB T4B 2B7 ACCESS MINI STORAGE 21211 - 100 AVENUE EDMONTON AB T5T 5X8 ACCESS SELF AND RV STORAGE 14255 100 ST. -

Economic Incentives and Compliance Report INDIANA ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT CORPORATION

Economic Incentives and Compliance Report INDIANA ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT CORPORATION For the Reporting Period January 1, 2005 – June 30, 2013 Indiana Economic Development Corporation | One North Capitol, Suite 700 | Indianapolis, Indiana 46204 800.463.8081 | tel 317.232.8800 | fax 317.232.4146 | iedc.in.gov ECONOMIC INCENTIVES AND COMPLIANCE REPORT For the Reporting Period January 1, 2005 – June 30, 2013 in thousands of new jobs for A MESSAGE FROM: Hoosiers and an improved standard of living. How do we do that? This report will give you the details so you are better able to understand how your tax dollars Dear Fellow Hoosiers: are being used to make your State The Indiana Economic better for you and your family. Development Corporation, which Our goal is to support and was formed in 2005 to succeed the VICTOR P. SMITH encourage our business economy, SECRETARY OF COMMERCE Department of Commerce, in alignment with the goals outlined continues to excel in new and in Governor Pence’s Roadmap for innovative ways. We’re a team of Making Indiana the State that professionals: sales managers, Works. See the Roadmap at marketing specialists, strategists, www.in.gov/gov/2530.htm. These and financial analysts to name a include increasing private sector few. We are the State that Works. employment, attracting new Our strategy has been a investment especially in certain resounding success. Since 2005, as sectors (manufacturing, the following report shows, we’ve agriculture, life sciences and played an integral role in bringing logistics), and improving our ERIC DODEN Hoosier workforce. PRESIDENT new businesses to Indiana, resulting Page 1 ECONOMIC INCENTIVES AND COMPLIANCE REPORT For the Reporting Period January 1, 2005 – June 30, 2013 To accomplish those goals, we understanding, stating how many performing and if they are meeting work with established contacts, jobs the company plans to create, or exceeding expectations. -

1. Appendix 1 Codes Prep Codes, Data Element 751

VOLVO Applications of ASC 12 Version: 9705-4 Published 2005-02-10 1. Appendix 1 Codes Prep Codes, Data element 751 00 According to Drawing 01 No Surface Treatment 02 Primer, Undercoats or Corr. Finish 03 Rustproof, parts ‘Y700/3’ 04 Top Coat 05 Zinc-plating 06 Hot Zinc Coat 09 Prep According to separate notes 14 Top Coat, Black 15 Top Coat, Black, High Gloss Packaging Codes, Data element 754 A Vendor packs in VTNA multiple package quantity B Vendor packages individually in suitable container C Vendor packs multiple components into individual kits D VTNA packs in selling multiple (corr container) E VTNA packs in selling multiple (merchandising carton) F VTNA packs individually (corr container) G VTNA packs individually (merchandise carton) H VTNA packs individually (wood crate) K VTNA packs multiple components into kits L VTNA packages individually (polybag) M VTNA packs in selling multiple (polybag) N Vendor: quantity ordered is for sets not pieces P VTNA special packaging instructions S Please cut and supply in .... foot lengths T Vendor cut and supply in .... meter lengths Z Package to VTNA work instruction 930.350 issue 02 VV Description gives an extended code, the Volvo company involved will gives a separate instruction about the codes. Appendix 1 Codes 1:1 VOLVO Applications of ASC 12 Version: 9705-4 Published 2005-02-10 Ship/Delivery or Calendar Pattern Codes, Data element 678 Code Description A Monday through Friday B Monday through Saturday C Monday through Sunday D Monday E Tuesday F Wednesday G Thursday H Friday J Saturday K Sunday L Monday through Thursday M Immediately N As Directed O Daily Mon. -

ITGBL Local Agents

ITGBL Local Agents Country: Afghanistan Post: Kabul Bureau: SCA Local Agents: 2) AES Cargo Share-E-Naw, Charahi Ansari Kabul, Afghanistan POC: Greg Forgrave Tel: 93-70-296-492 Cell: 93-70-274-374 Email: [email protected] 1) PAXTON International House #1, Corner of Shura and Park Streets Karte Seh Kabul, Afghanistan POC: Wali Mohammad Wasif Tel: 93 (0) 70 295 329 Cell: 0093 (0) 700 29 53 29 Email: [email protected] Website: www.paxton.com Country: Albania Post: Tirana Bureau: EUR Local Agents: 1) AES Cargo/ Move One Rruga "Brigada e VIII" P. Teknoprojekt Sh.2 Ap 3/2 Nr. 33/1 Tirana, Albania POC: Glenda Pajo Tel: 355 4 225 8103 Cell: 355 69 206 7269 Email: [email protected] 2) AGS Tirana Ish Kombinati I Tekstileve Fabrika e Ngyrosjes Tirana, Albania POC: Genti Jacellari Tel: 355 4 235 2560 x113 Fax: 355 69 208 6315 Email: [email protected] Wednesday, July 21, 2010 Page 1 of 152 ITGBL Local Agents Country: Algeria Post: Algiers Bureau: NEA Local Agents: 2) Algeria Moving and Shipping 13 Lot Beau Sejour La Sapiniere No. 7 Birmandreis Algers, Algeria POC: Mme. Ahlem Menar, GM Tel/Fax: 213-21-56-48-53 Cell: 213-0770-415-261 1) Deminter Algeria Rue Lakhder Manaa Cite 19 & 2 BT C No. 1 Ben Aknoon Alger, Algerie POC: Mr. Mohamed Meghiref, GM Tel: 213-21-91-57-92/ 213-21-91-57-94 Fax: 213-21-91-67-62/ 213-21-91-24-82 Cell: 213-61-51-27-38 Madjid Meghiref Cell: 213- 550 614 494 Amine Meghiref Email: [email protected] Country: Angola Post: Luanda Bureau: AF Local Agents: 1) EMP-TRANS Cargo Center Lds. -

TT100 For-Hire 07 Online.Qxd

A Word From the Publisher n this 2007 edition of the Trans- The shift to private owner- port Topics Top 100 For-Hire ship is also reflected in the pur- Carriers, the focus has shifted chase of Swift Transportation from Main Street to Wall Street. by its former chairman Jerry Private equity investment firms Moyes and the proposed buy- have become the driving force for out of U.S. Xpress Enterprises I by top executives of that com- change, based on our annual review of financial and operating statistics pany. for the nation’s top for-hire trucking No one knows how long this companies. trend will last, or even how suc- Of course, well-heeled investors cessful these new investment and Wall Street money managers strategies will be over the long have been involved in trucking term. But what is clear from a before, but today’s breed of money reading of the Transport Topics men appears to be taking a different Top 100 For-Hire Carriers list approach than did the corporate is a sense that the game has raiders in the 1980s who used high- Howard S. Abramson changed. interest debt to target vulnerable With private equity funds companies. And they are different from the Inter- providing a source of new capital, many carriers net-inspired corporate roll-ups that we saw in the are making investments in technology and 1990s when small companies were patched expanding services in order to increase their together to create new, bigger businesses that share of the freight market. were assumed to have magical superhero market They say you can’t tell the players without a power. -

Speaker Bios

36TH ANNUAL SEMINAR PRESENTED BY Wednesday, April 24th, 2019 Chicago’s Multi-Modal CSCMP CHICAGO, NASSTRAC, 8:00 am – 6:00 pm Supply Chain: and the TRAFFIC CLUB OF CHICAGO Air, Water, Rail, and Road Union League Club of Chicago SPEAKER BIOS George Abernathy Stephen Bindbeutel President Director of Product Solutions FreightWaves Truckstop.com George Abernathy is President at Stephen Bindbeutel grew up in the Metro FreightWaves. In this role, George over- Detroit area. After graduating from sees all revenue generating activities Michigan State University with a degree for the company and is flanked by one in Economics, he moved to Atlanta to of the deepest benches in the freight join AT&T’s Leadership Development startup scene. Program. Prior to joining FreightWaves,, Abernathy led the Transflo sales Bindbeutel joined Truckstop.com in Chicago as Director of Product and business development organization. He has also served as Solutions after spending nearly five years in the transportation President of Transplace during the company’s rapid ascension industry at Coyote Logistics. During that time he focused on into becoming a top 3PL, managing billions in North American understanding Carrier/Driver challenges, finding ways to make freight spend. Also at Transplace, he held the role of Executive the freight industry more efficient, and improving the digital Vice President and Chief Operating Officer and was a key products that helped carriers run their business. contributor in the company’s sale to Greenbriar Equity Partners in 2013. At Truckstop.com he will continue to work on improving digital service offerings, enhancing overall user experience, and will In addition to Transflo and Transplace, Abernathy has had an ex- lead the organization’s emerging technology and transportation tensive career that includes more than 30 years of supply chain market research. -

1991 Rail Vs Truck Fuel Efficiency

Rail vs. Truck Fuel Efficiency: U.S. Department The Relative Fuel Efficiency of Truck of Transportation Competitive Rail Freight and Federal Railroad Administration Truck Operations Compared in a Range of Corridors Office of Policy FINAL REPORT Abacus Technology Corporation Chevy Chase, Maryland Moving America New Directions, New Opportunities DOT/FRA/RRP-91/2 April 1991 Document is available to the public through the National Technical Information Service, Springfield, VA 22161 Technical Report Documentation Page 1 • R e p o rt N o . 2. Government Accession No. 3. Recipient's Catolog No. FRA-RRP-91-02 4. Title and Subtitle 5. Report Date Rail vs Truck Fuel Efficiency: The Relative Fuel Efficiency of Truck Competitive Rail Freight and Truck 6. Performing Organizotion Code Operations Compared in a Range of Corridors 8. -Performing Organization Report No. 7. Authors) Abacus Technology Corporation 9. Performing Organization Name and Address 10. Work Unit No. (TRAIS) Abacus Technology Corporation 5454 Wisconsin Avenue, Suite 1100 11. Contract or Grant No. DTFR-53-90-C-00017 Chevy Chase, Maryland 20815 13. Type of Report and Period Covered 12. Sponsoring Agency Name and Address U.S. Department of Transportation Final Report Federal Railroad Administration Office of Policy, RRP-32 14. Sponsoring Agency Code Washington, DC 20590 Federal Railroad Admin. 15. Supplementary Notes William Gelston (Chief, Economic Studies Division, FRA), Project Sponsor Marilyn W. Klein (Senior Policy Analyst, FRA), Project Monitor 16. Abstract This report summarizes the findings of a study to evaluate the fuel efficiency of rail freight operations relative to competing truckload service. The objective of the study was to identify the circumstances in which rail freight service offers a fuel efficiency advantage over alternative truckload options, and to estimate the fuel savings associated with using rail service. -

Spring 2012 / Printemps 2012 PUBLISHED APRIL 2012 Tél

C A N A D I A N Spring/Printemps 2012 E H T The Bi-Annual Magazine and Directory of the Canadian Association of Movers/ RevueMOVER semestrielle et annuaire de l’Association canadienne des déménageurs INSIDE — À L’INTERIEUR REALTOR® Advice to Consumers — REALTOR® conseils aux consommateurs Membership Listings — Liste des membres Insurance ♦ since 1924 Protect Your BOTTOM LINE YOUR RISKS > OUR SOLUTIONS “ Helping you to defi ne your risks and control them in the most cost effi cient way” > Improve your risk profi le > Reduce future claims > Control insurance costs ♦ Representing Movers across the country for over 20 years 55 York Street, Suite 200 ♦ Dedicated moving account team Toronto, Ontario M5J 1R7 ♦ Family run and managed, 85 years of history, Phone 416-777-2722 over 55 professionals, licensed in all Provinces ♦ Bilingual service available Fax 416-777-2716 ♦ Proud supporter of CALL US: 1-877-364-4589 www.moversinsurance.ca Published by/publié par : CANADIAN DÉMÉNAGEUR Canadian Association of Movers/ L’Association canadienne des LE H déménageurs THE MOVER CANADIEN PO Box 30039 RPO New Westminster The Bi-Annual Magazine and Directory of the Canadian Association of Movers/ Thornhill, ON L4J 0C6 Revue semestrielle et annuaire de l’Association canadienne des déménageurs Tel.: toll free 1-866-860-0065 Spring 2012 / Printemps 2012 PUBLISHED APRIL 2012 Tél. : sans frais 1-877-656-4993 Fax/Téléc. : 905-764-0765 Email/courriel : [email protected] TABLE OF CONTENTS/TABLE DES MATIÈRES Website/Site web : www.mover.net © 2012 Canadian Association of Movers. Chairman’s Message All rights reserved. The contents of this 6 Message du président du conseil publication may not be reproduced by any means, in whole or in part, without the President’s Message prior written consent of the publisher. -

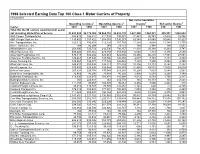

1998 Selected Earning Data Top 100 Class 1 Motor Carriers Of

1998 Selected Earning Data Top 100 Class 1 Motor Carriers of Property (thousands) Net carrier operating Operating revenues1 Operating expenses2 income3 Net carrier income4 Carrier 1997 1998 1997 1998 1997 1998 1997 1998 Total (for the 90 carriers reporting both years) - not including United Parcel Service 31,691,995 34,775,165 30,064,116 32,832,770 1,627,880 1,942,391 895,397 1,088,652 AAA Cooper Transportation 343,619 366,822 311,738 330,081 31,881 36,741 22,426 29,046 ABF Freight System, Inc. 1,136,402 1,157,822 1,074,053 1,090,273 62,349 67,549 30,645 37,923 Ace Transportation, Inc. 123,312 106,428 112,128 101,760 11,184 4,668 11,184 11,735 Acme Truck Line, Inc. NA 82,599 NA 79,751 NA 2,848 NA 2,637 Allied Systems, Ltd. 256,900 726,722 242,596 706,357 14,304 20,364 6,292 3,787 Allied Van Lines, Inc. 486,222 491,325 479,582 483,952 6,640 7,373 2,136 2,586 American Freightways, Inc. 870,319 986,286 825,063 926,076 45,256 60,210 17,801 27,501 Anderson Trucking Service, Inc. 149,663 147,998 145,586 140,650 4,077 7,348 7,201 4,349 Arrow Trucking Co. 125,067 134,471 117,742 126,622 7,325 7,850 2,084 2,395 Atlas Van Lines, Inc. 348,410 385,998 338,213 372,884 10,196 13,113 5,242 7,292 Averitt Express, Inc.