NVIS Fact Sheet MVG 18 – Heathlands

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Toward a Resolution of Campanulid Phylogeny, with Special Reference to the Placement of Dipsacales

TAXON 57 (1) • February 2008: 53–65 Winkworth & al. • Campanulid phylogeny MOLECULAR PHYLOGENETICS Toward a resolution of Campanulid phylogeny, with special reference to the placement of Dipsacales Richard C. Winkworth1,2, Johannes Lundberg3 & Michael J. Donoghue4 1 Departamento de Botânica, Instituto de Biociências, Universidade de São Paulo, Caixa Postal 11461–CEP 05422-970, São Paulo, SP, Brazil. [email protected] (author for correspondence) 2 Current address: School of Biology, Chemistry, and Environmental Sciences, University of the South Pacific, Private Bag, Laucala Campus, Suva, Fiji 3 Department of Phanerogamic Botany, The Swedish Museum of Natural History, Box 50007, 104 05 Stockholm, Sweden 4 Department of Ecology & Evolutionary Biology and Peabody Museum of Natural History, Yale University, P.O. Box 208106, New Haven, Connecticut 06520-8106, U.S.A. Broad-scale phylogenetic analyses of the angiosperms and of the Asteridae have failed to confidently resolve relationships among the major lineages of the campanulid Asteridae (i.e., the euasterid II of APG II, 2003). To address this problem we assembled presently available sequences for a core set of 50 taxa, representing the diver- sity of the four largest lineages (Apiales, Aquifoliales, Asterales, Dipsacales) as well as the smaller “unplaced” groups (e.g., Bruniaceae, Paracryphiaceae, Columelliaceae). We constructed four data matrices for phylogenetic analysis: a chloroplast coding matrix (atpB, matK, ndhF, rbcL), a chloroplast non-coding matrix (rps16 intron, trnT-F region, trnV-atpE IGS), a combined chloroplast dataset (all seven chloroplast regions), and a combined genome matrix (seven chloroplast regions plus 18S and 26S rDNA). Bayesian analyses of these datasets using mixed substitution models produced often well-resolved and supported trees. -

Flora.Sa.Gov.Au/Jabg

JOURNAL of the ADELAIDE BOTANIC GARDENS AN OPEN ACCESS JOURNAL FOR AUSTRALIAN SYSTEMATIC BOTANY flora.sa.gov.au/jabg Published by the STATE HERBARIUM OF SOUTH AUSTRALIA on behalf of the BOARD OF THE BOTANIC GARDENS AND STATE HERBARIUM © Board of the Botanic Gardens and State Herbarium, Adelaide, South Australia © Department of Environment, Water and Natural Resources, Government of South Australia All rights reserved State Herbarium of South Australia PO Box 2732 Kent Town SA 5071 Australia © 2012 Board of the Botanic Gardens & State Herbarium, Government of South Australia J. Adelaide Bot. Gard. 25 (2012) 71–96 © 2012 Department of Environment, Water and Natural Resources, Govt of South Australia Notes on Hibbertia (Dilleniaceae) 8. Seven new species, a new combination and four new subspecies from subgen. Hemistemma, mainly from the central coast of New South Wales H.R. Toelkena & R.T. Millerb a State Herbarium of South Australia, DENR Science Resource Centre, P.O. Box 2732, Kent Town, South Australia 5071 E-mail: [email protected] b 13 Park Road, Bulli, New South Wales 2516 E-mail: [email protected] Abstract Increased collections from the Hibbertia-rich vicinity of Sydney, New South Wales, prompted a survey of rarer species to publicise the need for more information ahead of the rapid urban spread. Many of these species were previously misunderstood or are listed as rare and endangered. Thirteen new taxa (in bold) are described and discussed in context with the following seventeen taxa within seven different species groups: 1. H. acicularis group: H. woronorana Toelken; 2. H. humifusa group: H. -

The Role of Fire in the Ecology of Leichhardt's Grasshopper (Petasida Ephippigera) and Its Food Plants, Pityrodia Spp

The role of fire in the ecology of Leichhardt's grasshopper (Petasida ephippigera) and its food plants, Pityrodia spp. Piers Hugh Barrow B. Sc. (University of Queensland) Hons. (Northern Territory University) A thesis submitted to satisfy the requirements for the award of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Institute of Advanced Studies, School for Environmental Research, Charles Darwin University, Darwin, Australia. March 2009 I hereby declare that the work herein, now submitted as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy is the result of my own investigations, and all references to ideas and work of other researchers have been specifically acknowledged. I hereby certify that the work embodied in this thesis has not already been accepted in substance for any degree, and is not being currently submitted in candidature for any other degree. Piers Barrow March 2009 i Acknowledgements My partner Cate Lynch provided support and encouragement, field assistance, proof- reading and editing, and forewent much of what is expected in normal life for a such a long time through this project, and I am deeply grateful. My supervisors Peter Whitehead, Barry Brook, Jeremy Russell-Smith and Stephen Garnett provided valuable advice and discussion, and, despite typically huge workloads, never failed to make themselves available to help. I am particularly indebted to Peter Whitehead, who shouldered most of the work, way beyond expectations, and provided guidance and insight throughout, and to Jeremy Russell-Smith, who has encouraged and facilitated my interest in the ecology of the Top End in general, and of the sandstone country and fire in particular, for many years. -

Handbook of Grasses, Treating of Their Structure, Classification

Young collector ."9' 910 JAN: W„HUTCHINSON ONE SEIinNG BOUGHT WITH THE INCOME OF THE SAGE ENDOWMENT FUND THE GIFT OF HENRY W. SAGE 1891 ALBERT R. MANN LIBRARY New York State Colleges OF Agriculture and Human Ecology AT Cornell University Cornell University Library QK 495.G74H97 1910 •'e''*'"9 Handbook of grasses, "UJimirn^' 3 1924 001 738 933 Cornell University Library The original of tliis book is in tlie Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/details/cu31924001738933 Poa annua, the Annual Meadow-grass ; flowering. This Book is now publislitd by GEORGE ALLEN' & UNWIN, LTD. Ruskiii House, 40, MUSEUM STREET, LONDON^ W.C. Poa anmia, the Annual Meadow-grassj floweidns HANDBOOK OF GRASSES TREATING OF THEIR STRUCTURE, CLASSIFICATION, GEOGRAPHICAL DISTRIBUTION AND USES ALSO DESCRIBING THE BRITISH SPECIES AND THEIR HABITATS BY WILLIAM HUTCHINSON XonOon SONNENSCHEIN & CO., Lim. , SWAN New York : THE MACMILLAN CO. igio Edition, March iSgg; Third Edition igob; First Edition, SeftembeiiSgs; Second Fourth Edition, igio. PREFACE Grasses are in three respects a remarkable family : they possess many structural peculiarities which sharply define them from all other kinds of plants ; they are so abundant and widely diffused as to constitute the dominant feature of the landscape, not only in our own, but in most other coun- tries j and lastly, no other Order can at all compare with the Gramineffi in the variety and magnitude of their uses. Yet the study of grasses, so far from being popular, is shunned by many botanists in the belief that it is beset with unusual difficulties ; farmers and graziers, to whom the cereal and forage grasses are all in all, have rarely a scientific acquaintance with them ; while those observers of Nature, not particularly iriterested in either botany or agriculture, are hardly able to recognize two or three among the many species which everywhere abound. -

Edition 2 from Forest to Fjaeldmark the Vegetation Communities Highland Treeless Vegetation

Edition 2 From Forest to Fjaeldmark The Vegetation Communities Highland treeless vegetation Richea scoparia Edition 2 From Forest to Fjaeldmark 1 Highland treeless vegetation Community (Code) Page Alpine coniferous heathland (HCH) 4 Cushion moorland (HCM) 6 Eastern alpine heathland (HHE) 8 Eastern alpine sedgeland (HSE) 10 Eastern alpine vegetation (undifferentiated) (HUE) 12 Western alpine heathland (HHW) 13 Western alpine sedgeland/herbland (HSW) 15 General description Rainforest and related scrub, Dry eucalypt forest and woodland, Scrub, heathland and coastal complexes. Highland treeless vegetation communities occur Likewise, some non-forest communities with wide within the alpine zone where the growth of trees is environmental amplitudes, such as wetlands, may be impeded by climatic factors. The altitude above found in alpine areas. which trees cannot survive varies between approximately 700 m in the south-west to over The boundaries between alpine vegetation communities are usually well defined, but 1 400 m in the north-east highlands; its exact location depends on a number of factors. In many communities may occur in a tight mosaic. In these parts of Tasmania the boundary is not well defined. situations, mapping community boundaries at Sometimes tree lines are inverted due to exposure 1:25 000 may not be feasible. This is particularly the or frost hollows. problem in the eastern highlands; the class Eastern alpine vegetation (undifferentiated) (HUE) is used in There are seven specific highland heathland, those areas where remote sensing does not provide sedgeland and moorland mapping communities, sufficient resolution. including one undifferentiated class. Other highland treeless vegetation such as grasslands, herbfields, A minor revision in 2017 added information on the grassy sedgelands and wetlands are described in occurrence of peatland pool complexes, and other sections. -

May Plant Availability List

May 2021: Plants Available—While They Last! Plants listed below are available to purchase at Norrie's Gift & Garden Shop, currently open Wednesday–Sundays 11:00 am-2:00 pm. New plants are delivered each week. Please wear a mask and be mindful of physical distancing. Arboretum members receive 10% off on plants and other items not already discounted; Many plants are also available to buy online (shopucscarboretum.com) and pick up at Norrie's by appointment; Thank you for supporting the Arboretum! AUSTRALIAN PLANTS Acacia myrtifolia Darwinia citriodora 'Seaspray' Hakea salicifolia ‘Gold Medal’ Actinodium cunninghamii Darwinia leiostyla 'Mt Trio' Hakea scoparia Adenanthos cuneatus 'Coral Drift' Dendrobium kingianum Hardenbergia violacea 'Mini Haha' Adenanthos dobsonii Dodonaea adenophora Hardenbergia violacea 'White Out' Adenanthos sericeus subsp. sericeus Eremaea hadra Hibbertia truncata Adenanthos x cunninghamii Eremophila subteretifolia Hypocalymma cordfolium 'Golden Veil' Agonis flexuosa 'Jervis Bay Afterdark' Feijoa sellowiana Isopogon anemonifolius 'Mt. Wilson' Banksia 'Giant Candles' Gastrolobium celsianum Isopogon formosus Banksia integrifolia Gastrolobium minus Kennedia nigricans Banksia integifolia 'Roller Coaster' Gastrolobium praemorsum 'Bronze Butterfly' Kennedia prostrata Banksia marginata 'Minimarg' Gastrolobium truncatum Kunzea badjensis 'Badja Blush' Banksia occidentalis Grevillea 'Bonfire' Kunzea baxteri Banksia spinulosa 'Nimble Jack' Grevillea 'Canterbury Gold' Kunzea parvifolia Banksia spinulosa 'Red Rock' Grevillea ‘Cherry -

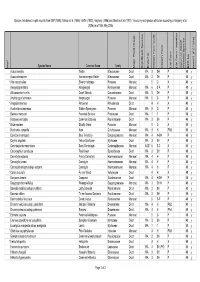

BFS048 Site Species List

Species lists based on plot records from DEP (1996), Gibson et al. (1994), Griffin (1993), Keighery (1996) and Weston et al. (1992). Taxonomy and species attributes according to Keighery et al. (2006) as of 16th May 2005. Species Name Common Name Family Major Plant Group Significant Species Endemic Growth Form Code Growth Form Life Form Life Form - aquatics Common SSCP Wetland Species BFS No kens01 (FCT23a) Wd? Acacia sessilis Wattle Mimosaceae Dicot WA 3 SH P 48 y Acacia stenoptera Narrow-winged Wattle Mimosaceae Dicot WA 3 SH P 48 y * Aira caryophyllea Silvery Hairgrass Poaceae Monocot 5 G A 48 y Alexgeorgea nitens Alexgeorgea Restionaceae Monocot WA 6 S-R P 48 y Allocasuarina humilis Dwarf Sheoak Casuarinaceae Dicot WA 3 SH P 48 y Amphipogon turbinatus Amphipogon Poaceae Monocot WA 5 G P 48 y * Anagallis arvensis Pimpernel Primulaceae Dicot 4 H A 48 y Austrostipa compressa Golden Speargrass Poaceae Monocot WA 5 G P 48 y Banksia menziesii Firewood Banksia Proteaceae Dicot WA 1 T P 48 y Bossiaea eriocarpa Common Bossiaea Papilionaceae Dicot WA 3 SH P 48 y * Briza maxima Blowfly Grass Poaceae Monocot 5 G A 48 y Burchardia congesta Kara Colchicaceae Monocot WA 4 H PAB 48 y Calectasia narragara Blue Tinsel Lily Dasypogonaceae Monocot WA 4 H-SH P 48 y Calytrix angulata Yellow Starflower Myrtaceae Dicot WA 3 SH P 48 y Centrolepis drummondiana Sand Centrolepis Centrolepidaceae Monocot AUST 6 S-C A 48 y Conostephium pendulum Pearlflower Epacridaceae Dicot WA 3 SH P 48 y Conostylis aculeata Prickly Conostylis Haemodoraceae Monocot WA 4 H P 48 y Conostylis juncea Conostylis Haemodoraceae Monocot WA 4 H P 48 y Conostylis setigera subsp. -

Introduction Methods Results

Papers and Proceedings Royal Society ofTasmania, Volume 1999 103 THE CHARACTERISTICS AND MANAGEMENT PROBLEMS OF THE VEGETATION AND FLORA OF THE HUNTINGFIELD AREA, SOUTHERN TASMANIA by J.B. Kirkpatrick (with two tables, four text-figures and one appendix) KIRKPATRICK, J.B., 1999 (31:x): The characteristics and management problems of the vegetation and flora of the Huntingfield area, southern Tasmania. Pap. Proc. R. Soc. Tasm. 133(1): 103-113. ISSN 0080-4703. School of Geography and Environmental Studies, University ofTasmania, GPO Box 252-78, Hobart, Tasmania, Australia 7001. The Huntingfield area has a varied vegetation, including substantial areas ofEucalyptus amygdalina heathy woodland, heath, buttongrass moorland and E. amygdalina shrubbyforest, with smaller areas ofwetland, grassland and E. ovata shrubbyforest. Six floristic communities are described for the area. Two hundred and one native vascular plant taxa, 26 moss species and ten liverworts are known from the area, which is particularly rich in orchids, two ofwhich are rare in Tasmania. Four other plant species are known to be rare and/or unreserved inTasmania. Sixty-four exotic plantspecies have been observed in the area, most ofwhich do not threaten the native biodiversity. However, a group offire-adapted shrubs are potentially serious invaders. Management problems in the area include the maintenance ofopen areas, weed invasion, pathogen invasion, introduced animals, fire, mechanised recreation, drainage from houses and roads, rubbish dumping and the gathering offirewood, sand and plants. Key Words: flora, forest, heath, Huntingfield, management, Tasmania, vegetation, wetland, woodland. INTRODUCTION species with the most cover in the shrub stratum (dominant species) was noted. If another species had more than half The Huntingfield Estate, approximately 400 ha of forest, the cover ofthe dominant one it was noted as a codominant. -

Special Issue3.7 MB

Volume Eleven Conservation Science 2016 Western Australia Review and synthesis of knowledge of insular ecology, with emphasis on the islands of Western Australia IAN ABBOTT and ALLAN WILLS i TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ABSTRACT 1 INTRODUCTION 2 METHODS 17 Data sources 17 Personal knowledge 17 Assumptions 17 Nomenclatural conventions 17 PRELIMINARY 18 Concepts and definitions 18 Island nomenclature 18 Scope 20 INSULAR FEATURES AND THE ISLAND SYNDROME 20 Physical description 20 Biological description 23 Reduced species richness 23 Occurrence of endemic species or subspecies 23 Occurrence of unique ecosystems 27 Species characteristic of WA islands 27 Hyperabundance 30 Habitat changes 31 Behavioural changes 32 Morphological changes 33 Changes in niches 35 Genetic changes 35 CONCEPTUAL FRAMEWORK 36 Degree of exposure to wave action and salt spray 36 Normal exposure 36 Extreme exposure and tidal surge 40 Substrate 41 Topographic variation 42 Maximum elevation 43 Climate 44 Number and extent of vegetation and other types of habitat present 45 Degree of isolation from the nearest source area 49 History: Time since separation (or formation) 52 Planar area 54 Presence of breeding seals, seabirds, and turtles 59 Presence of Indigenous people 60 Activities of Europeans 63 Sampling completeness and comparability 81 Ecological interactions 83 Coups de foudres 94 LINKAGES BETWEEN THE 15 FACTORS 94 ii THE TRANSITION FROM MAINLAND TO ISLAND: KNOWNS; KNOWN UNKNOWNS; AND UNKNOWN UNKNOWNS 96 SPECIES TURNOVER 99 Landbird species 100 Seabird species 108 Waterbird -

Plant Life of Western Australia

INTRODUCTION The characteristic features of the vegetation of Australia I. General Physiography At present the animals and plants of Australia are isolated from the rest of the world, except by way of the Torres Straits to New Guinea and southeast Asia. Even here adverse climatic conditions restrict or make it impossible for migration. Over a long period this isolation has meant that even what was common to the floras of the southern Asiatic Archipelago and Australia has become restricted to small areas. This resulted in an ever increasing divergence. As a consequence, Australia is a true island continent, with its own peculiar flora and fauna. As in southern Africa, Australia is largely an extensive plateau, although at a lower elevation. As in Africa too, the plateau increases gradually in height towards the east, culminating in a high ridge from which the land then drops steeply to a narrow coastal plain crossed by short rivers. On the west coast the plateau is only 00-00 m in height but there is usually an abrupt descent to the narrow coastal region. The plateau drops towards the center, and the major rivers flow into this depression. Fed from the high eastern margin of the plateau, these rivers run through low rainfall areas to the sea. While the tropical northern region is characterized by a wet summer and dry win- ter, the actual amount of rain is determined by additional factors. On the mountainous east coast the rainfall is high, while it diminishes with surprising rapidity towards the interior. Thus in New South Wales, the yearly rainfall at the edge of the plateau and the adjacent coast often reaches over 100 cm. -

By H.D.V. PRENDERGAST a Thesis Submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy of the Australian National University. January 1

STRUCTURAL, BIOCHEMICAL AND GEOGRAPHICAL RELATIONSHIPS IN AUSTRALIAN c4 GRASSES (POACEAE) • by H.D.V. PRENDERGAST A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of the Australian National University. January 1987. Canberra, Australia. i STATEMENT This thesis describes my own work which included collaboration with Dr N .. E. Stone (Taxonomy Unit, R .. S .. B.S .. ), whose expertise in enzyme assays enabled me to obtain comparative information on enzyme activities reported in Chapters 3, 5 and 7; and with Mr M.. Lazarides (Australian National Herbarium, c .. s .. r .. R .. O .. ), whose as yet unpublished taxonomic views on Eragrostis form the basis of some of the discussion in Chapter 3. ii This thesis describes the results of research work carried out in the Taxonomy Unit, Research School of Biological Sciences, The Australian National University during the tenure of an A.N.U. Postgraduate Scholarship. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS My time in the Taxonomy Unit has been a happy one: I could not have asked for better supervision for my project or for a more congenial atmosphere in which to work. To Dr. Paul Hattersley, for his help, advice, encouragement and friendship, I owe a lot more than can be said in just a few words: but, Paul, thanks very much! To Mr. Les Watson I owe as much for his own support and guidance, and for many discussions on things often psittacaceous as well as graminaceous! Dr. Nancy Stone was a kind teacher in many days of enzyme assays and Chris Frylink a great help and friend both in and out of the lab •• Further thanks go to Mike Lazarides (Australian National Herbarium, c.s.I.R.O.) for identifying many grass specimens and for unpublished data on infrageneric groups in Eragrostis; Dr. -

Vicariance, Climate Change, Anatomy and Phylogeny of Restionaceae

Botanical Journal of the Linnean Society (2000), 134: 159–177. With 12 figures doi:10.1006/bojl.2000.0368, available online at http://www.idealibrary.com on Under the microscope: plant anatomy and systematics. Edited by P. J. Rudall and P. Gasson Vicariance, climate change, anatomy and phylogeny of Restionaceae H. P. LINDER FLS Bolus Herbarium, University of Cape Town, Rondebosch 7701, South Africa Cutler suggested almost 30 years ago that there was convergent evolution between African and Australian Restionaceae in the distinctive culm anatomical features of Restionaceae. This was based on his interpretation of the homologies of the anatomical features, and these are here tested against a ‘supertree’ phylogeny, based on three separate phylogenies. The first is based on morphology and includes all genera; the other two are based on molecular sequences from the chloroplast genome; one covers the African genera, and the other the Australian genera. This analysis corroborates Cutler’s interpretation of convergent evolution between African and Australian Restionaceae. However, it indicates that for the Australian genera, the evolutionary pathway of the culm anatomy is much more complex than originally thought. In the most likely scenario, the ancestral Restionaceae have protective cells derived from the chlorenchyma. These persist in African Restionaceae, but are soon lost in Australian Restionaceae. Pillar cells and sclerenchyma ribs evolve early in the diversification of Australian Restionaceae, but are secondarily lost numerous times. In some of the reduction cases, the result is a very simple culm anatomy, which Cutler had interpreted as a primitively simple culm type, while in other cases it appears as if the functions of the ribs and pillars may have been taken over by a new structure, protective cells developed from epidermal, rather than chlorenchyma, cells.