Thermopylae and Rise of an Empire

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Female Property Ownership and Status in Classical and Hellenistic Sparta

Female Property Ownership and Status in Classical and Hellenistic Sparta Stephen Hodkinson University of Manchester 1. Introduction The image of the liberated Spartiate woman, exempt from (at least some of) the social and behavioral controls which circumscribed the lives of her counterparts in other Greek poleis, has excited or horrified the imagination of commentators both ancient and modern.1 This image of liberation has sometimes carried with it the idea that women in Sparta exercised an unaccustomed influence over both domestic and political affairs.2 The source of that influence is ascribed by certain ancient writers, such as Euripides (Andromache 147-53, 211) and Aristotle (Politics 1269b12-1270a34), to female control over significant amounts of property. The male-centered perspectives of ancient writers, along with the well-known phenomenon of the “Spartan mirage” (the compound of distorted reality and sheer imaginative fiction regarding the character of Spartan society which is reflected in our overwhelmingly non-Spartan sources) mean that we must treat ancient images of women with caution. Nevertheless, ancient perceptions of their position as significant holders of property have been affirmed in recent modern studies.3 The issue at the heart of my paper is to what extent female property-holding really did translate into enhanced status and influence. In Sections 2-4 of this paper I shall approach this question from three main angles. What was the status of female possession of property, and what power did women have directly to manage and make use of their property? What impact did actual or potential ownership of property by Spartiate women have upon their status and influence? And what role did female property-ownership and status, as a collective phenomenon, play within the crisis of Spartiate society? First, however, in view of the inter-disciplinary audience of this volume, it is necessary to a give a brief outline of the historical context of my discussion. -

Ancient Sparta Was a Warrior Society in Ancient Greece That Reached

Ancient Sparta was a warrior society in ancient Greece that reached the height of its power after defeating rival city-state Athens in the Peloponnesian War (431-404 B.C.). Spartan culture was centered on loyalty to the state and military service. At age 7, Spartan boys entered a rigorous state-sponsored education, military training and socialization program. Known as the Agoge, the system emphasized duty, discipline and endurance. Although Spartan women were not active in the military, they were educated and enjoyed more status and freedom than other Greek women. Because Spartan men were professional soldiers, all manual labor was done by a slave class, the Helots. Despite their military prowess, the Spartans’ dominance was short-lived: In 371 B.C., they were defeated by Thebes at the Battle of Leuctra, and their empire went into a long period of decline. SPARTAN SOCIETY Sparta was an ancient Greek city-state located primarily in the present-day region of southern Greece called Laconia. The population of Sparta consisted of three main groups: the Spartans who were full citizens; the Helots, or serfs/slaves; and the Perioeci, who were neither slaves nor citizens. The Perioeci, whose name means “dwellers-around,” worked as craftsmen and traders, and built weapons for the Spartans. 3 Layers of ‘Social Stratification’ ← Top Tier: Spartan Male Warriors and Spartan Women ← Middle Tier: Non Warriors, not full citizens, considered to be outside of true Spartan society. These were artisans and merchants who made weapons and did business with the Spartans. (Perioeci) ← Helots or slaves. These were people who were conquered by the Spartans. -

Ancient Greek Society by Mark Cartwright Published on 15 May 2018

Ancient Greek Society by Mark Cartwright published on 15 May 2018 Although ancient Greek Society was dominated by the male citizen, with his full legal status, right to vote, hold public oce, and own property, the social groups which made up the population of a typical Greek city-state or polis were remarkably diverse. Women, children, immigrants (both Greek and foreign), labourers, and slaves all had dened roles, but there was interaction (oen illicit) between the classes and there was also some movement between social groups, particularly for second-generation ospring and during times of stress such as wars. The society of ancient Greece was largely composed of the following groups: male citizens - three groups: landed aristocrats (aristoi), poorer farmers (periokoi) and the middle class (artisans and traders). semi-free labourers (e.g the helots of Sparta). women - belonging to all of the above male groups but without citizen rights. children - categorised as below 18 years generally. slaves - the douloi who had civil or military duties. foreigners - non-residents (xenoi) or foreign residents (metoikoi) who were below male citizens in status. Classes Although the male citizen had by far the best position in Greek society, there were dierent classes within this group. Top of the social tree were the ‘best people’, the aristoi. Possessing more money than everyone else, this class could provide themselves with armour, weapons, and a horse when on military campaign. The aristocrats were oen split into powerful family factions or clans who controlled all of the important political positions in the polis. Their wealth came from having property and even more importantly, the best land, i.e.: the most fertile and the closest to the protection oered by the city walls. -

300: Greco-Persian Wars 300: the Persian Wars — Rule Book

300: Greco-Persian Wars 300: The Persian Wars — Rule book 1.0 Introduction Illustration p. 2 City "300" has as its theme the war between Persia and Name Greece which lasted for 50 years from the Ionian Food Supply Revolt in 499 BC to the Peace of Callias in 449 BC Road One player plays the Greek army, based around Blue Ear of Wheat = Supply city for the Greek Athens and Sparta, and the other the Persian army. Army During these fifty years launched three expeditions ■ Red = Important city for the Persian army to Greece but in the game they may launch up to Athens is a port five. Corinth is not a port Place name (does not affect the game) 2.0 Components 2.1.4 Accumulated Score Track: At the end of The game is played using the following elements. each expedition, note the difference in score between the two sides. At the end of the game, the 2.1 Map player who leads on accumulated score even by one point, wins the game. If the score is 0, the result is a The map covers Greece and a portion of Asia Minor draw. in the period of the Persian Wars. 2.1.5 Circles of Death/Ostracism: These contain 2.1.1 City: Each box on the map is a city, the images of individuals who died or were containing the following information: ostracised in the course of the game. When this • Name: the name of the city. occurs, place an army or fleet piece in the indicated • Important City: the red cities are important for the circle. -

The Effects of Mythos' on Plato's Educational Approach

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Elsevier - Publisher Connector Available online at www.sciencedirect.com Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences 55 ( 2012 ) 560 – 567 INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON NEW HORIZONS IN EDUCATION INTE2012 The Effects of Mythos’ on Plato's Educational Approach Derya Çığır Dikyola aIstanbul University Hasan Ali Yucel Education Faculty, Department of Social Science, Istanbul, Turkey. Abstract The purpose of this study, by examining the findings related to education in Greek mythos, is to reveal Plato's contributions to the educational approach. The similarities and differences between Plato’s educational approach and the education in Mythos are emphasized in this historical - comparison based study. The effect of mythos, which in fact give ideal education of the period, with the expressions they made about Gods’ and heroes’ education, on the educational approach of Plato, known to be intensely against the mythos, is rather surprising. ©© 20122012 Published Published by byElsevier Elsevier Ltd. SelectionLtd. Selection and/or peer-reviewand/or peer-review under responsibility under responsibility of The Association of The of Association Science, of EducationScience, Educationand Technology and TechnologyOpen access under CC BY-NC-ND license. Keywords: educational approach, educational history, mythology. 1. Introduction Plato is the first thinker of philosophy as well as of education. His ideas about education still have influence on schooling. Thus; Plato is a decent starting point in the studies over the meaning and the philosophy of education. Thinkers like Aristoteles, John Locke, J. J. Rousseau, and John Dewey, who produced education theories couldn’t help challenging Plato. -

Copyrighted Material

9781405129992_6_ind.qxd 16/06/2009 12:11 Page 203 Index Acanthus, 130 Aetolian League, 162, 163, 166, Acarnanians, 137 178, 179 Achaea/Achaean(s), 31–2, 79, 123, Agamemnon, 51 160, 177 Agasicles (king of Sparta), 95 Achaean League: Agis IV and, agathoergoi, 174 166; as ally of Rome, 178–9; Age grades: see names of individual Cleomenes III and, 175; invasion grades of Laconia by, 177; Nabis and, Agesilaus (ephor), 166 178; as protector of perioecic Agesilaus II (king of Sparta), cities, 179; Sparta’s membership 135–47; at battle of Mantinea in, 15, 111, 179, 181–2 (362 B.C.E.), 146; campaign of, in Achaean War, 182 Asia Minor, 132–3, 136; capture acropolis, 130, 187–8, 192, 193, of Phlius by, 138; citizen training 194; see also Athena Chalcioecus, system and, 135; conspiracies sanctuary of after battle of Leuctra and, 144–5, Acrotatus (king of Sparta), 163, 158; conspiracy of Cinadon 164 and, 135–6; death of, 147; Acrotatus, 161 Epaminondas and, 142–3; Actium, battle of, 184 execution of women by, 168; Aegaleus, Mount, 65 foreign policy of, 132, 139–40, Aegiae (Laconian), 91 146–7; gift of, 101; helots and, Aegimius, 22 84; in Boeotia, 141; in Thessaly, Aegina (island)/Aeginetans: Delian 136; influence of, at Sparta, 142; League and,COPYRIGHTED 117; Lysander and, lameness MATERIAL of, 135; lance of, 189; 127, 129; pro-Persian party on, Life of, by Plutarch, 17; Lysander 59, 60; refugees from, 89 and, 12, 132–3; as mercenary, Aegospotami, battle of, 128, 130 146, 147; Phoebidas affair and, Aeimnestos, 69 102, 139; Spartan politics and, Aeolians, -

The Riddle of Ancient Sparta: Unwrapping the Enigma

29 May 2018 The Riddle of Ancient Sparta: Unwrapping the Enigma PROFESSOR PAUL CARTLEDGE (Sir Winston) Churchill once famously referred to Soviet Russia as ‘a riddle wrapped in a mystery inside an enigma’. My title is a simplified version of that seemingly obscure remark. The point of contact and comparison between ancient Sparta and modern Soviet Russia is the nature of the evidence for them, and the way in which they have been imagined and represented, by outsiders. There was a myth - or mirage – of ancient Sparta, as there was of Soviet Russia: typically, the outsider who commented was both very ignorant and either wildly PRO or – as in Churchill’s case – wildly ANTI. There was no moderate, middle way. The ‘Spartan Tradition’ (Elizabeth Rawson) is alive and – well, ‘well’ to this day. To start us off, I give you a relatively gentle, deliberately inoffensive and very British example of the PRO myth, mirage, legend or tradition of ancient Sparta. In 2017 Terry’s of York confectioners would have been celebrating its 150th anniversary, had it not been taken over by Kraft in 1993. A long discontinued but still long cherished Terry’s line was their ‘Spartan’ assortment: hard-centre chocolates, naturally. Because the Spartans were the ultimate ancient warriors, uber-warriors, if you like. And their fearsome reputation on the battlefield had won them not just respect but fame – and not just in antiquity: think only of the Battle of Thermopylae in 480 BCE – and of the movie 300. But of course the Spartans were no mere chocolate box soldiers - they were the real thing, the hard men of ancient Greece. -

When the Fighting Men of Sparta Stormed the Gates of Thermopylae, They Found in Its Records This Mysterious Entry: Prisoner #667, the Man in the Golden Mask

*big awesome credits splash on screen* Narrator: When the fighting men of Sparta stormed the gates of Thermopylae, they found in its records this mysterious entry: Prisoner #667, the Man in the Golden Mask. Narrator: *rifles notes* Shit. Wrong movie. Here we go: Narrator: In Sparta, we kill the deformed at birth. *Close-up of Skull Pit of Doom.* Narrator: We put our children through unimaginable tortures from the time they are old enough to hold a sword. *Close-up of kid getting beaten up.* Narrator: We abuse them constantly and allow them no rest. *Close-up of kid getting beaten up in front of other kids.* Narrator: We make them bleed for even sneezing wrong. *Close-up of kid getting beaten up more. There seems to be a Theme here.* Narrator: Then we send them, up the hill, both ways, barefoot, to fight the Fenris Wolf in the freezing cold. *Close-up of kid looking tough.* Audience: Isn't that Scandinav-- Narrator: SHUT UP! *Close-up of kid looking even tougher.* Audience: But why do they do all of this?? Narrator: It builds character! Audience: Goooooo Sparta! *Leonidas returns to Sparta wearing the wolf skin, where everyone else has to bow to him in the freezing cold - because everywhere else, kneeling is submission, but in Sparta, kneeling in the snow builds character.* Narrator: Then Leonidas came back to Sparta, which as you'll notice is a gold, gold place. Leonidas: Ahhhh, shining Sparta-- Audience: We know. Hot Queen Chick: Leonidas, I'm sorry to interrupt your son-torturing, but there's a messenger here. -

Not All Were Created Equal

Portland State University PDXScholar Young Historians Conference 2010-2011 Past Young Historians Conference Winners May 1st, 9:00 AM - 10:00 AM Not All Were Created Equal Sarah Cox Clackamas High School Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/younghistorians Part of the Ancient History, Greek and Roman through Late Antiquity Commons, History of Gender Commons, and the Women's History Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Cox, Sarah, "Not All Were Created Equal" (2011). Young Historians Conference. 3. https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/younghistorians/2010-2011/oralpres/3 This Event is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Young Historians Conference by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. Cox 1 Sarah Cox LPB Western Civilization: Fall Paper 9 December 2010 Not All Were Created Equal “The man’s role requires him to be outside – men who stay at home during the day are considered womanish – the woman’s requires her to work at home” (McAuslan 137). In the time-period between 700 and 300 BCE, this was often true for the women of the world, but there was one major exception: Spartan women. In most other parts of ancient Greece, women were expected to be seen and not heard. Spartan women, however, were allowed much more freedom than their contemporaries. They were allowed to own property, could live independently, and were not forced into marriage and motherhood at a young age. -

A Brief History of Classical Education

A Brief History of Classical Lesson 4: The History of Ancient Education Education Dr. Matthew Post Outline: Ancient Education and Its Questions Ancient Education is all about character formation. The question is “What sort of character?” What are the morals towards which to form students? Scholé presents another issue. Ancients had less time to devote to proper scholé. The presence of corporeal punishment was questioned by many because it seemed to treat students as slaves (coercing them to do their work through physical pain). The “intellectual life” caused controversy because it often raised questions that unsettled the normal order. (i.e. Cicero held that the ideas of the Stoics made people complacent in the face of evil and some held that Plato’s ideas inspired people to go and assassinate the ruler of their town) Roman Education Three outcomes: Philosopher, Statesman, and Soldier Discussion of Liberal Arts originates in Rome especially with Cicero (without formalization of Medieval period) Education connected to the idea of pietas (from which we get the English words “piety” and “pity”). Pietas does not mean “piety,” it means “loyalty.” o Pietas is loyalty to one’s family, people, city, and the gods. Loyalty to the gods is what the English notion of piety refers to, but pietas encompasses more. Traditional Roman education is dictated by the paterfamilias (the head of the family – a father with power over all and everything in the family). “Aeneas & Anchises” by Pierre Lepautre (a famous show of pietas) o The paterfamilias often educated the children himself. (Famously Cato the Elder educated his children.) Education in the Roman family was for both men and women though they were educated differently. -

Ancient Sparta Ancient Athens

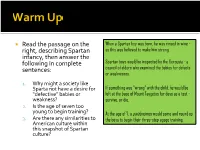

Read the passage on the When a Spartan boy was born, he was rinsed in wine - right, describing Spartan as this was believed to make him strong. infancy, then answer the following in complete Spartan boys would be inspected by the Gerousia - a sentences: council of elders who examined the babies for defects or weaknesses. 1. Why might a society like Sparta not have a desire for If something was “wrong” with the child, he would be “defective” babies or left at the base of Mount Taygetus for days as a test - weakness? survive, or die. 2. Is the age of seven too young to begin training? At the age of 7, a paidonómos would come and round up 3. Are there any similarities to the boys to begin their three-step agoge training. American culture within this snapshot of Spartan culture? Title: Comparative Study; Eastern Bloc and Worldly Civilizations Date: Know: I will be able to identify, describe, and analyze the similarities and differences of political involvement in livelihood across millennia. Relevance: Today we are learning about this because it is imperative to build knowledge in a pragmatic way – understanding that the real world and real life are connected to history is very important. Coming to this understanding is powerful! Do: I will write and discuss comparative issues between Ancient Greek city-states Do: I will write and discuss comparative issues between Medieval nations Do: I will write and discuss comparative issues between modern countries Write down the Essential Question: EQ: which child-rearing system had the greatest impact on population regulation? Warm Up Cornell Notes . -

VALOUR, DUTY, SACRIFICE: SPARTA ‘In Sparta Are to Be Found Those Who Are Most Enslaved and Those Who Are the Most Free.’

CHAPTER 2 VALOUR, DUTY, SACRIFICE: SPARTA ‘In Sparta are to be found those who are most enslaved and those who are the most free.’ CRITIAS OF ATHENS sample pages Spartan infantry in a formation called a phalanx. 38 39 CHAPTER 2 VALOUR, DUTY, SACRIFICE: SPARTA KEY POINTS KEY CONCEPTS OVERVIEW • At the end of the Dark Age, the Spartan polis emerged DEMOCRACY OLIGARCHY TYRANNY MONARCHY from the union of a few small villages in the Eurotas valley. Power vested in the hands Power vested in the hands A system under the control A system under the control • Owing to a shortage of land for its citizens, Sparta waged of all citizens of the polis of a few individuals of a non-hereditary ruler of a king war on its neighbour Messenia to expand its territory. unrestricted by any laws • The suppression of the Messenians led to a volatile slave or constitution population that threatened Sparta’s way of life, making the DEFINITION need for reform urgent. KEY EVENTS • A new constitution was put in place to ensure Sparta could protect itself from this new threat, as well as from tyranny. Citizens of the polis all A small, powerful and One individual exercises Hereditary rule passing 800 BCE • Sweeping reforms were made that transformed Sparta share equal rights in the wealthy aristocratic class complete authority over from father to son political sphere all aspects of everyday life Sparta emerges from the into a powerful military state that soon came to dominate Most citizens barred from Family dynasties claim without constraint Greek Dark Age the Peloponnese.